Clinical Classification

Clinical assessment is based on medical history, physical examination, radiology, and endoscopy with biopsy. Radiologic examinations designed to demonstrate the presence of extrarectal or extracolonic metastasis may include chest radiographs, computed tomography (CT; abdomen, pelvis, chest), magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, positron emission tomography (PET), or fused PET/CT scans. Clinical stage (cTNM) then may be assigned. Pathological stage (pTNM) is assigned based on the resection specimen. Preoperative measurement of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is recommended, as CEA level reflects the likelihood that subclinical or clinical liver or lung metastases are present. In the event of recurrence or synchronous metastases, it now is recommended that the status of the genes KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF be evaluated and MSI or mismatch repair (MMR) be measured.

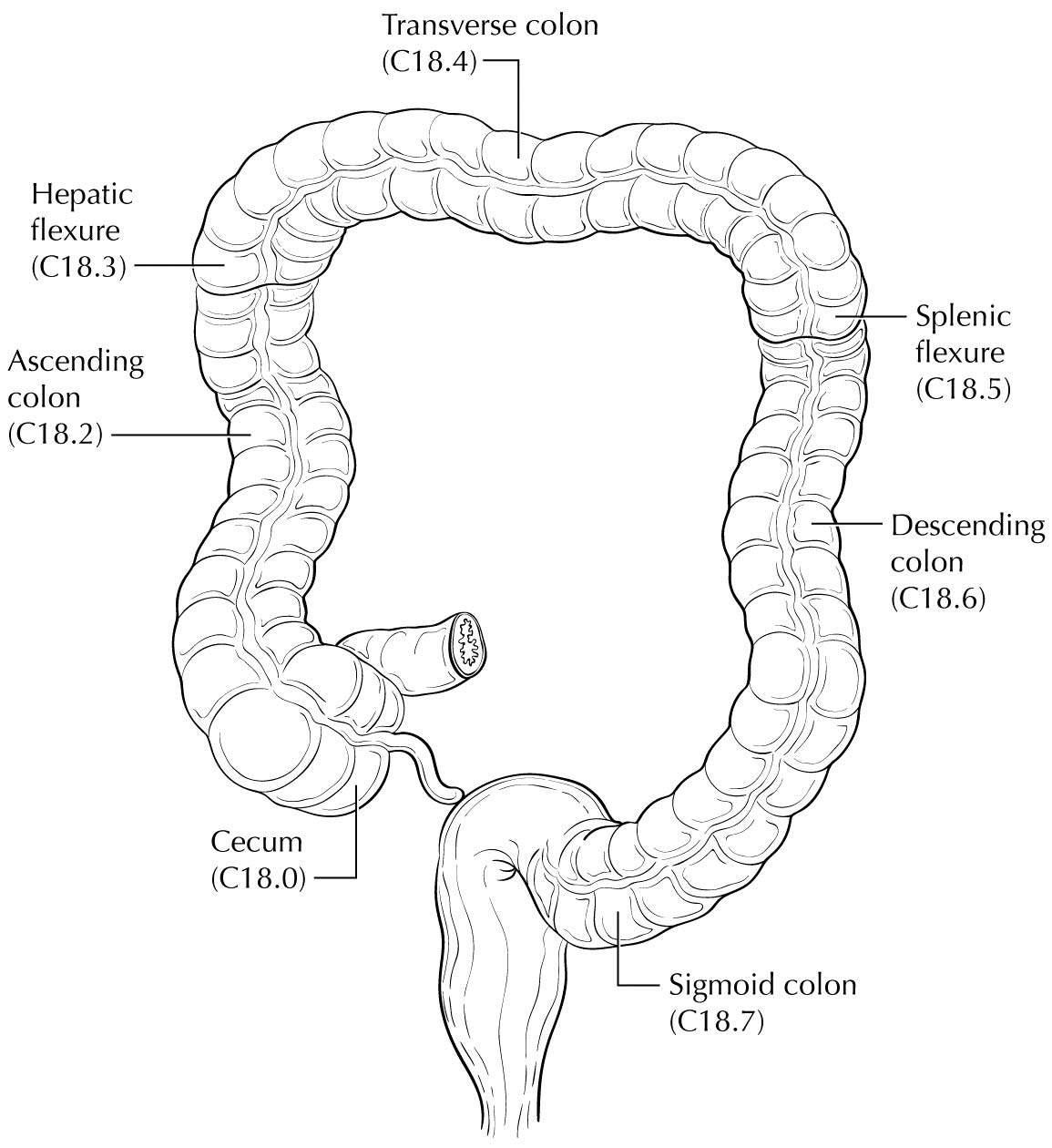

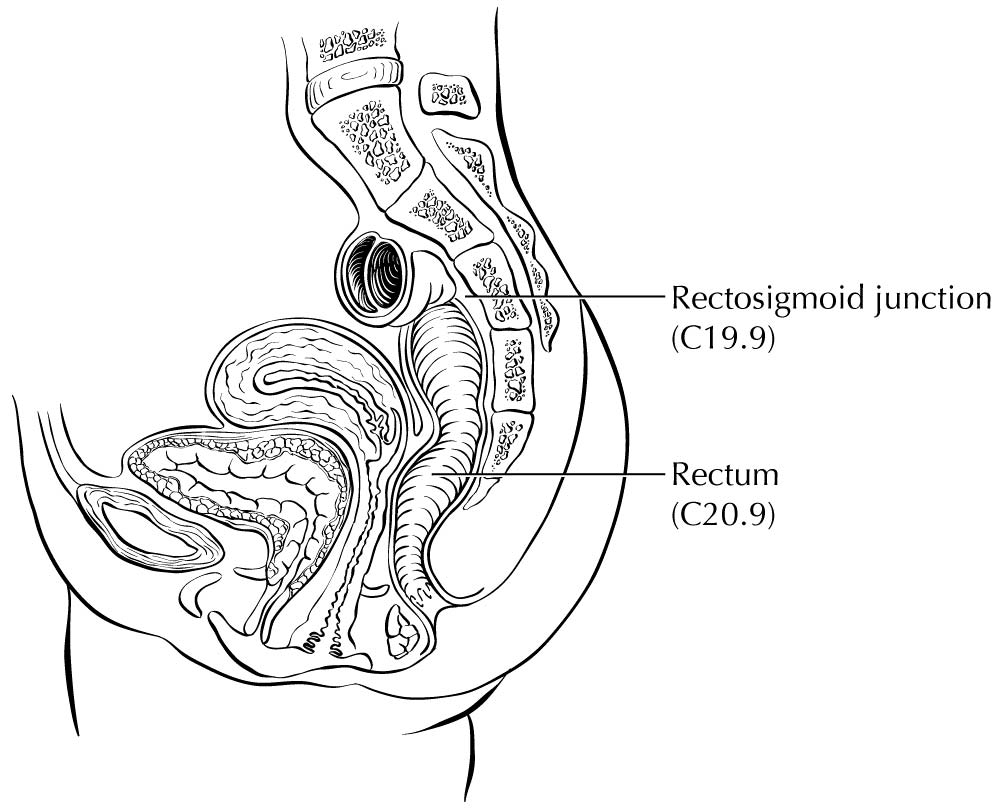

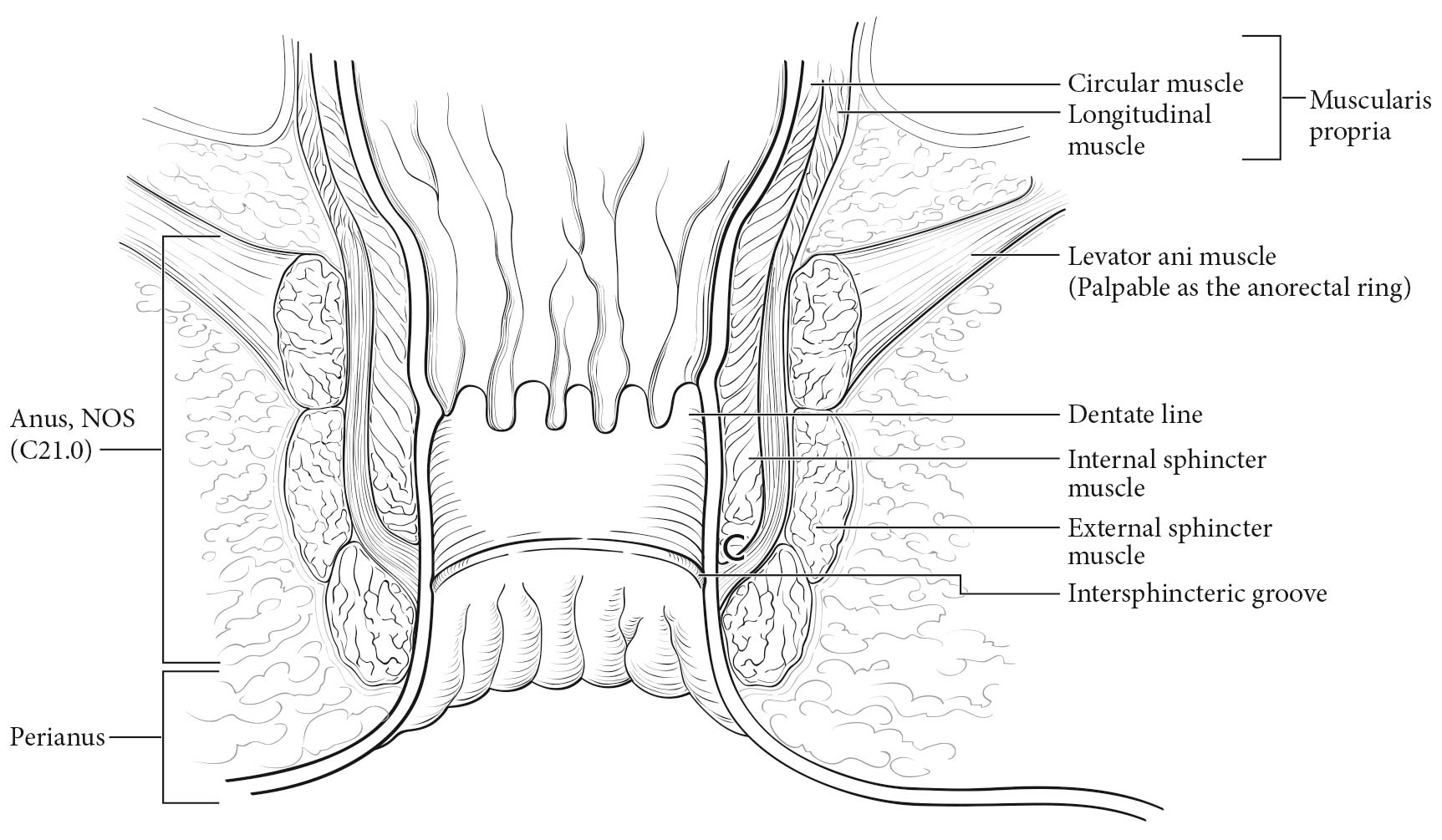

Primary Site(s)

Carcinoma arising at the ileocecal valve should be classified as colonic cancer. For staging purposes, adenocarcinomas should be classified as rectal cancers if proximal to the dentate line or anorectal ring on digital examination. Squamous carcinomas should be staged as anal canal cancers if they are distal to the dentate line or the anorectal ring. However, there are instances of rectal squamous carcinomas and anal adenocarcinomas in this area. The former may need to be treated according to anal squamous carcinoma regimens, whereas the anal adenocarcinomas may require surgery in addition to chemotherapy and radiation. For rectal cancers that extend beyond the dentate line, as for anal canal cancers, the superficial inguinal lymph nodes are among the regional nodal groups at risk for metastatic spread and are included in cN/pN analysis.

Carcinomas that arise in the colon or rectum spread by direct invasion into the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and subserosal tissue (or adventitia) of the bowel wall, and each level of penetration is annotated by a T category. Primary tumors also spread by invading lymphatics and blood vessels to form metastases in lymph nodes or distant sites; this is annotated by the N and M categories, respectively. In addition, carcinomas may spread and grow in the adventitia as discrete nodules of cells called tumor deposits. These characteristics, along with further description of the T categories, are described in detail later in the chapter.

For patients with rectal cancer, the pelvic extent of disease (cT and cN categories), combined with the status of extrapelvic metastasis (cM) and patient symptoms, determines whether preoperative adjuvant treatment is appropriate. The primary imaging modalities to assess the pelvic extent of disease are endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and pelvic MR imaging. To improve the accuracy of nodal staging, EUS may be augmented with fine-needle aspiration of lymph nodes suspicious for metastasis, but microscopic evidence of tumor by such a procedure is part of the clinical TNM (cTNM) staging. It is especially important that patients who will receive preoperative adjuvant treatment or neoadjuvant therapy be assigned a pretreatment clinical stage based on disease extent before beginning treatment (cTNM).1-4 Pathological stage is assigned if the patient undergoes resection, and a modified pathological stage is generated if the patient undergoes neoadjuvant therapy (ypTNM).

For carcinomas of the colon or rectum, the number of metastatic sites involved is an important prognostic factor and is reflected in the subdivision of M1, as described in greater detail later in the chapter. Metastases to both ovaries or both lobes of the lungs are considered involvement of a single site by themselves. Peritoneal carcinomatosis with or without blood-borne metastasis to visceral organs has a worse prognosis.

Imaging

As stated elsewhere in this chapter, several imaging studies may be performed in newly diagnosed colon or rectal carcinoma patients. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for evaluation of colon1 or rectal3 carcinoma cases recommend that a CT scan with intravenous and oral contrast be performed on the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. If the CT scan cannot be performed because of contrast sensitivity or the images are not adequate, then MR imaging with contrast may be performed with a noncontrast CT scan.1 PET/CT is recommended only if there is an equivocal finding on a contrast-enhanced CT scan or in the case of sensitivity to CT contrast. If synchronous metastases or distant metastases appear later and resection seems possible, then PET/CT should be considered to further delineate the extent of disease.1,3

Pathological Classification

Most cancers of the colon and many cancers of the rectum are pathologically staged after microscopic examination of the resected specimen (pTNM) resulting from surgical exploration of the abdomen and cancer-directed surgical resection.

Primary Tumor

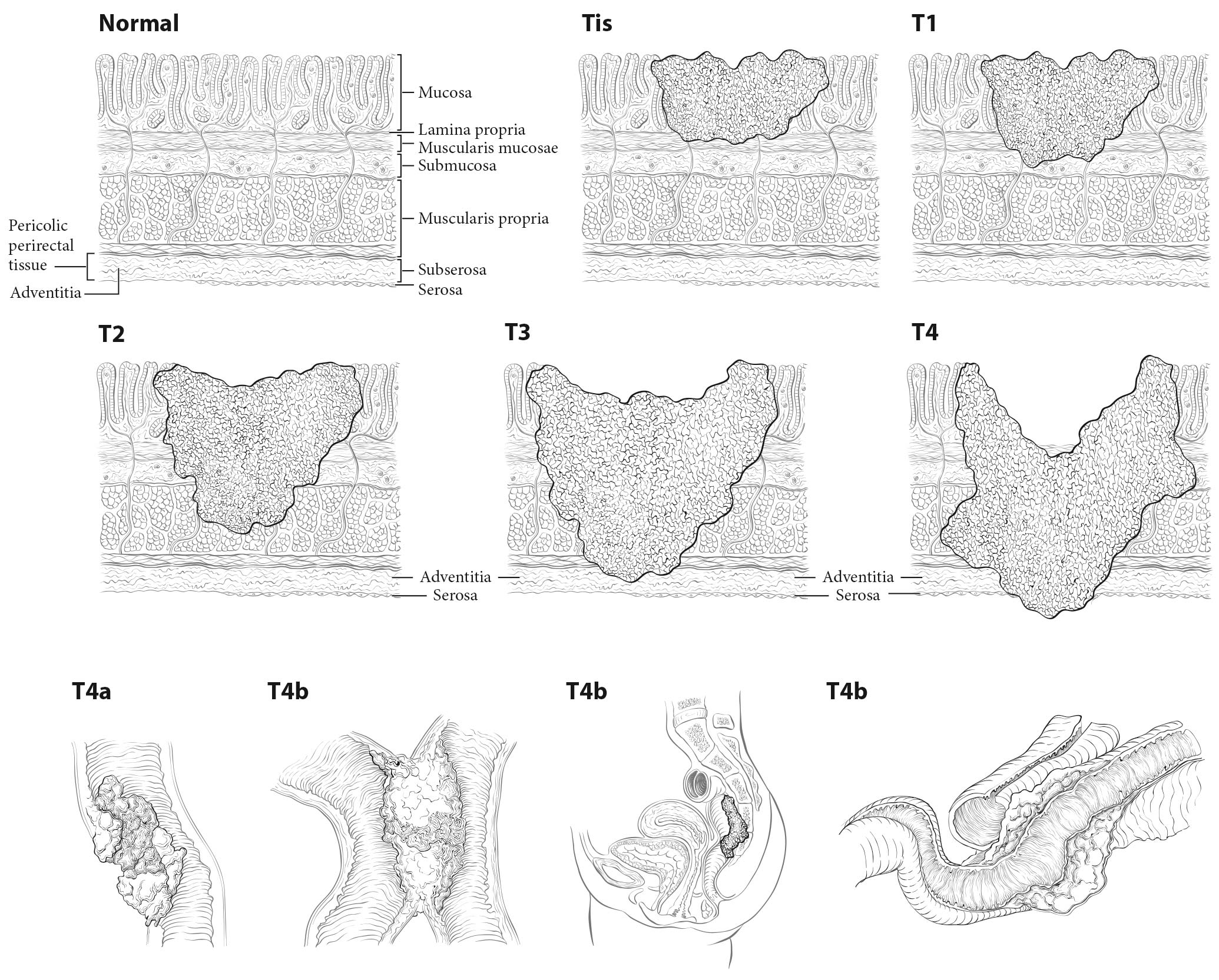

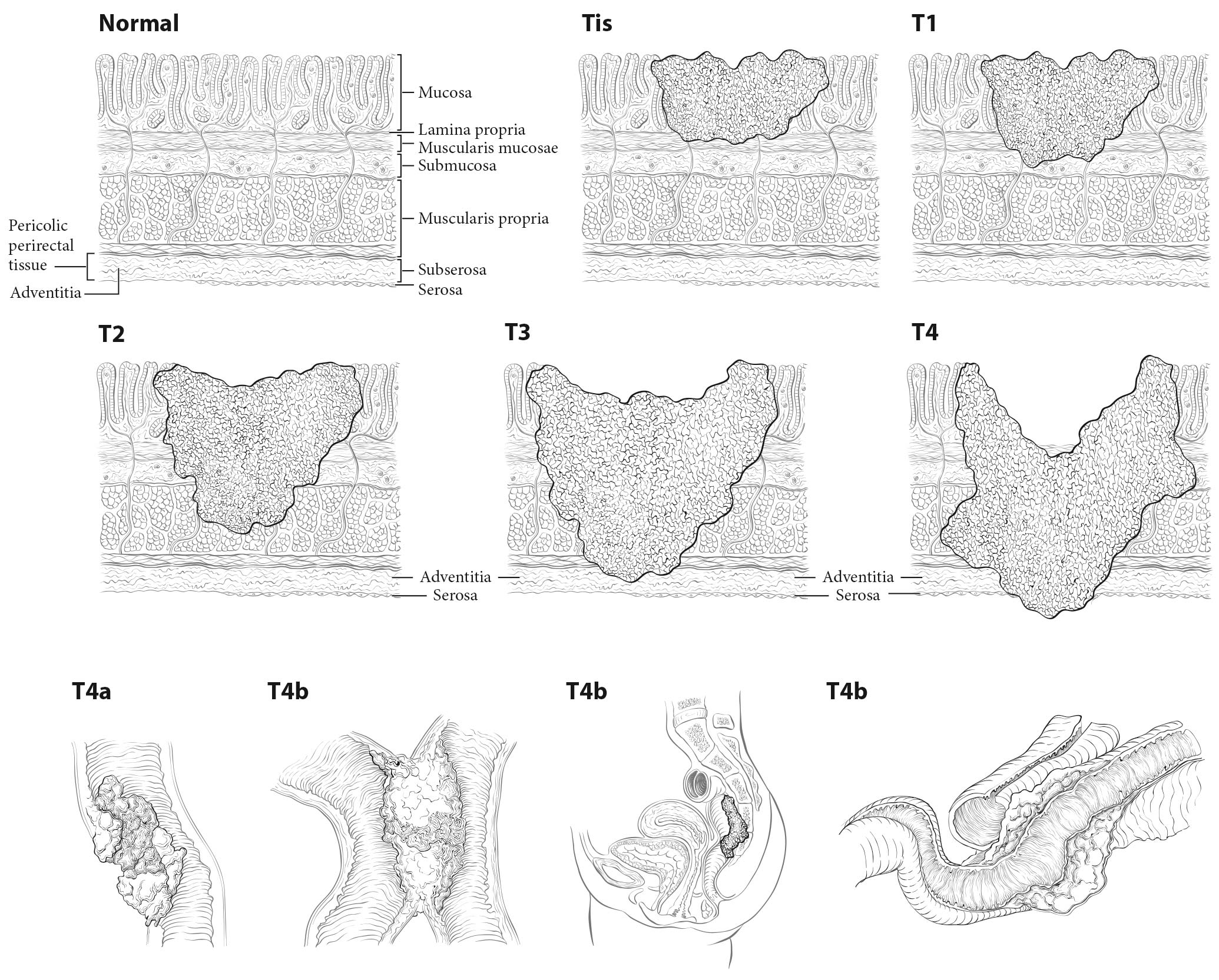

Tis and T1. Regarding the colorectum, pathologists apply the term high-grade dysplasia to lesions that are confined to the epithelial layer of crypts and lack invasion through the basement membrane into the lamina propria. The term intraepithelial carcinoma is synonymous with high-grade dysplasia but rarely is used to apply to the colorectum. High-grade dysplasia should not be assigned to the Tis category or recorded in cancer registries, because these lesions lack potential for tumor spread. However, Tis is assigned to lesions confined to the mucosa in which cancer cells invade into the lamina propria and may involve but not penetrate through the muscularis mucosa. (These lesions are more correctly termed intramucosal carcinoma.) Although invasion through the basement membrane in all gastrointestinal sites is considered invasive, in colorectal tumors, invasion of the lamina propria without penetration through the muscularis mucosa (intramucosal carcinoma) is designated Tis, as it is associated with a negligible risk for metastasis. Because there is potential for missing deeper invasion because of sampling, such lesions should be recorded in the cancer registry. The term invasive adenocarcinoma is used for colorectal cancer if the tumor extends through the muscularis mucosae into the submucosa or beyond (Figure 20.5).

20.5 T1-T3 as defined in Definition of Primary Tumor (T). T4 is a tumor that penetrates or perforates the visceral peritoneum in the parts of the colon or rectum covered only by peritoneum (T4a) or that invades an adjacent structure or organ (T4b).

Carcinoma in a Polyp. These lesions are classified according to the pT definitions adopted for colorectal carcinomas. For instance, invasive carcinoma limited to the muscularis mucosae and /or lamina propria is classified as pTis, whereas tumor that has invaded through the muscularis mucosae and has entered the submucosa of the polyp head or stalk is classified as pT1. pTis in a polyp resected with a clear margin during endoscopy is a Stage 0 carcinoma with nodal and metastatic status unknown, but with a sufficiently low probability of nodal involvement that node resection is not justified. The probability of metastasis is similarly low. Haggitt levels and submucosal depth of invasion categories may be used to classify polyps for their malignant potential, but reporting of these parameters is optional.5-10 Guidelines from several organizations1,3,4,11,12 and authors8,12,13 recommend surgical resection for polyps that contain high-grade carcinoma, have invasive carcinoma at or less than 1 mm from the resection margin, or have lymphatic/venous vessel invasion.

T1, T2, and T3. As in previous AJCC editions, these tumors are defined as involvement of the submucosa, penetration through the submucosa into but not through the muscularis propria, and penetration through the muscularis propria, respectively.14,15

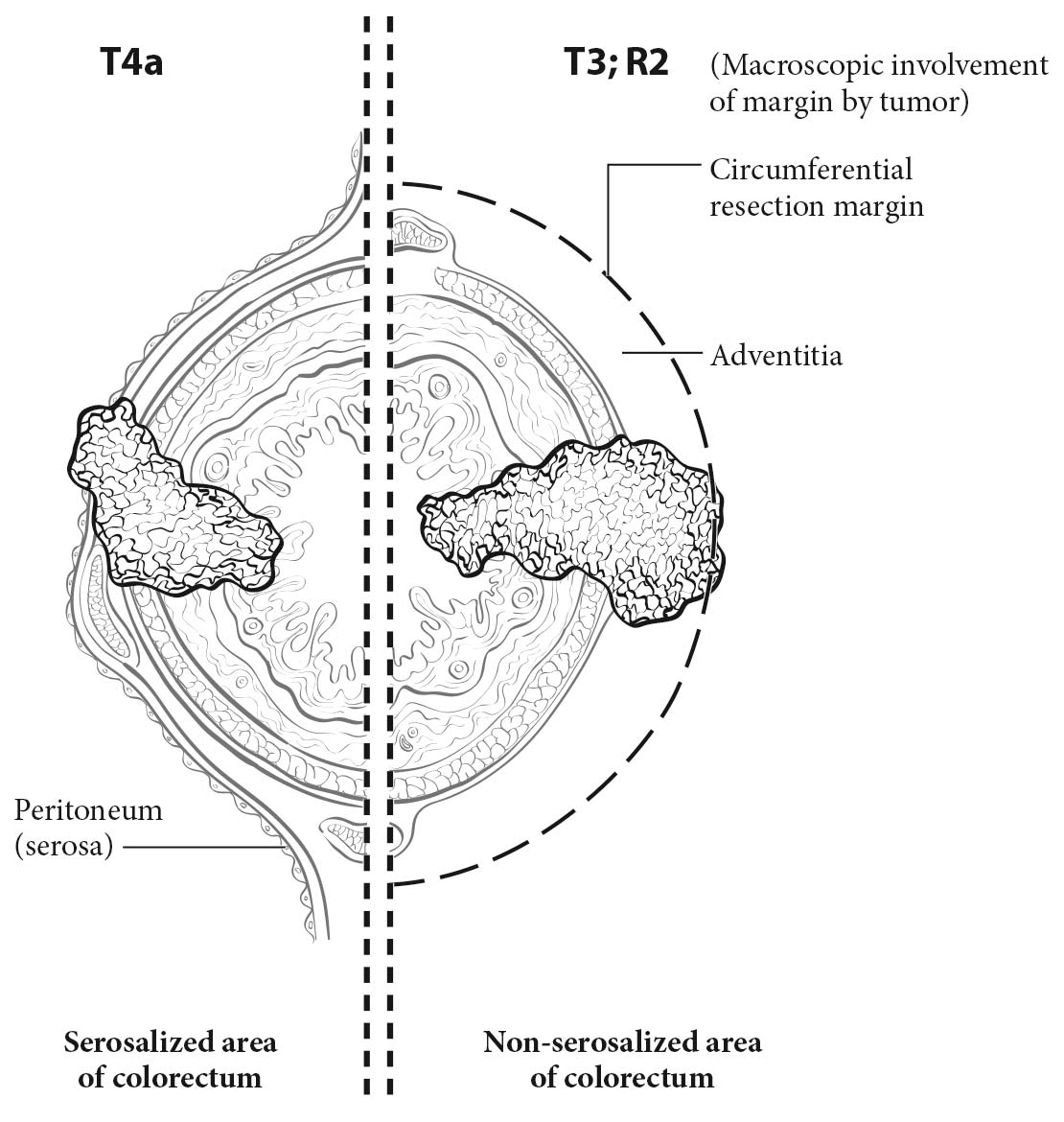

T4. Tumors that involve the serosal surface (visceral peritoneum) or directly invade adjacent organs or structures are assigned to the T4 category. For both colon and rectum, T4 is divided into two categories (T4a and T4b) based on different outcomes shown in expand ed datasets16,17 (Figures 20.6 and 20.7). T4a tumors are characterized by involvement of the serosal surface (visceral peritoneum) by direct tumor extension. Tumors with perforation in which the tumor cells are continuous with the serosal surface through inflammation also are considered T4a. The significance of tumors that are <1 mm from the serosal surface and accompanied by serosal reaction is unclear, with some18 but not all studies19 indicating a higher risk for peritoneal relapse. Multiple-level sections and /or additional tissue blocks of the tumor should be examined in these cases to detect serosal surface involvement. If the latter is not present after additional evaluation, the tumor should be assigned to the pT3 category. In portions of the colorectum that are not peritonealized (e.g., posterior aspects of the ascending and descending colon, lower portion of the rectum), the T4a category is not applicable.

Treatment of Primary Colorectal Carcinomas. Colon carcinomas are resected according to guidelines by several organizations.1-4 The stand ard of care for primary treatment of rectal carcinoma should include sharp dissection with an intact fascia propria of the mesorectum. The extent of mesorectal excision may be total (TME) or partial, as in the setting of proximal tumors located more than 5 cm from the distal extent of the mesorectum (tumor-specific mesorectal excision [TSME]). For the purpose of discussion throughout the rest of this chapter, TME is used to indicate either TME or TSME. The rate of local recurrence is inversely proportional to the completeness of the excision and the distance from the tumor to the circumferential resection margin (CRM).20-22 Thus, macroscopic assessment of the quality and completeness of the excision of the mesorectum and the state of the fascia propria should be reported for rectal cancers. As suggested by Parfitt and Driman,23 the College of American Pathologists (CAP) guidelines support a three-tiered evaluation system of a) complete, b) nearly complete, and c) incomplete (Table 20.1). The site-specific factor of the CRM is related to, but separate from, the grading of the TME specimen, as TME grading includes an assessment of the mesorectum for bulk, presence of surgical defects, degree of coning, and perforation. The CRM is described further elsewhere in the chapter and applies to the status of the nonserosal margin closest to the deepest point of penetration by the primary cancer throughout the colorectum.11 As indicated in the current CAP guidelines11 and in a systematic review,24 patients with an incomplete mesorectum after rectal resection have a worse outcome than those with a complete mesorectum. For those with a negative CRM, the quality of the TME specimen is especially important, because the recurrence rate is higher in those with incomplete specimens.

20.1 Grading of quality and completeness of the mesorectum in a total mesorectal excision

| | Mesorectum | Defects | Coning | CRM* |

|---|

| Complete | Intact, smooth | Not deeper than 5 mm | None | Smooth, regular |

| Nearly complete | Moderate bulk, irregular | No visible muscularis propria | Moderate | Irregular |

| Incomplete | Little bulk | Down to muscularis propria | Moderate/marked | Irregular |

Both the specimen as a whole (fresh) and cross-sectional slices (fixed) are examined to make an adequate interpretation (Adapted from Parfitt and Driman23 with permission). *CRM, circumferential resection margin. |

Tumor Regression after Neoadjuvant Preoperative Radiotherapy and /or Chemotherapy for Rectal Carcinoma

The pathological response to preoperative radiotherapy and /or chemotherapy is an important prognostic factor for rectal carcinoma. This response is assessed by the pathologist and is reported with the prefix y before a pT and pN. Both a large institutional study25 and a rand omized phase III trial26 demonstrated that complete eradication of the tumor, as detected by microscopic examination of the resected specimen, is associated with a better prognosis than an incomplete or poor response to neoadjuvant therapy. Failure of the tumor to respond to neoadjuvant treatment is an adverse prognostic factor. Parallel associations are observed in breast, esophageal, and pancreatic carcinomas. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the use of complete pathological response to neoadjuvant therapy as such a strong positive prognostic factor in breast cancer that it may be used as an end point for evaluating drug responses. In addition, measures of tumor response to therapy such as minimal residual disease in leukemias after induction therapy and necrosis after neoadjuvant treatment of osteosarcomas have similar prognostic impact.

According to the CAP guidelines for recording tumor regression, the resection specimen must be evaluated and recorded by the pathologist (see CAP's “Protocol for the Examination of Specimens from Patients with Carcinomas of the Colon and Rectum”11,12), because neoadjuvant chemoradiation in rectal cancer often is associated with significant tumor response and downstaging. Therefore, specimens from patients receiving neoadjuvant chemoradiation should be examined thoroughly at the primary tumor site, in regional nodes, and for peritumoral satellite nodules or deposits in the remainder of the specimen. It is especially important to evaluate the resection specimen for lymph node metastases, because nodal metastasis is an important poor prognostic factor.26

Lymph Nodes

In the assessment of pN, the number of lymph nodes sampled should be recorded. The number of nodes removed and retrieved from an operative specimen has been reported to correlate with improved survival, possibly because of increased accuracy in staging. For nodal sampling to be accurate, it is important to obtain and examine at least 12 lymph nodes in radical colon and rectum resections in patients who undergo surgery for cure. In cases in which tumor is resected for palliation, or in patients who have received preoperative radiation or chemoradiation, fewer lymph nodes may be present. In all cases, however, it is essential that the total number of regional lymph nodes recovered from the resection specimen be recorded, because that number is prognostically important. A pN0 determination is assigned if all nodes are histologically negative, even if fewer than the recommended number of nodes have been analyzed.

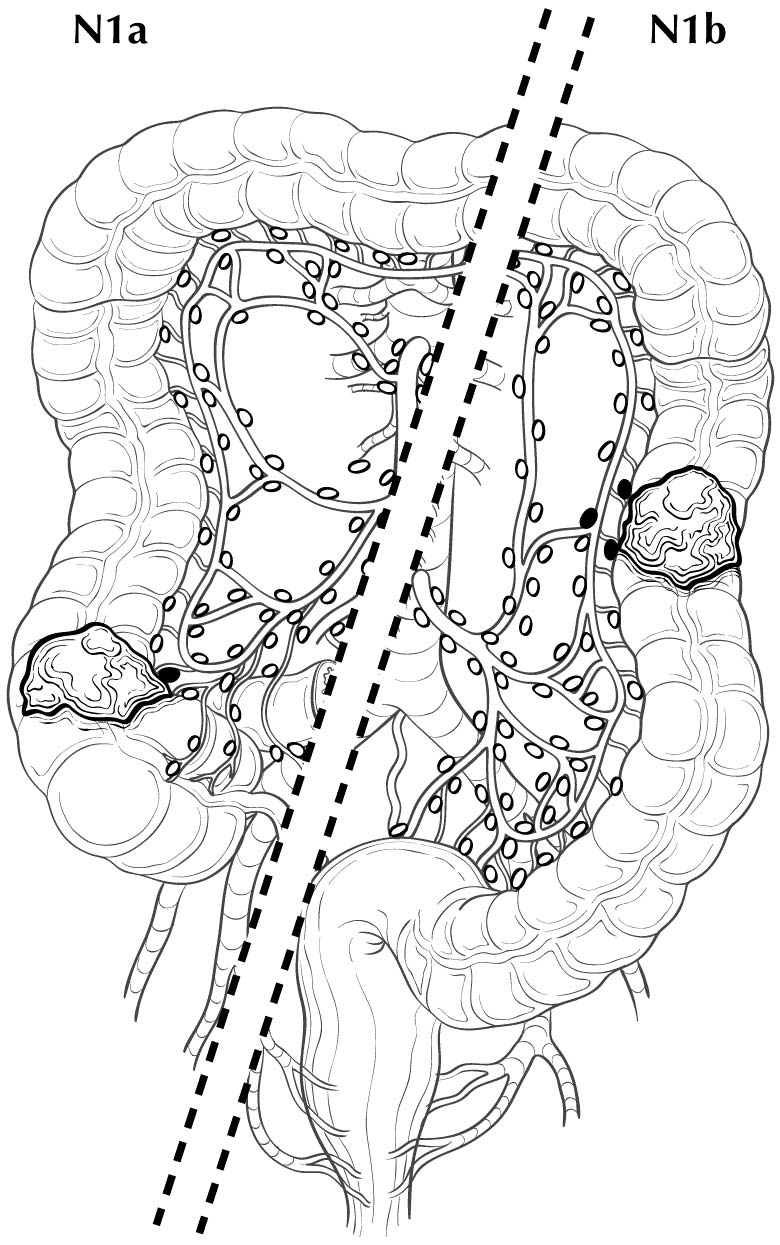

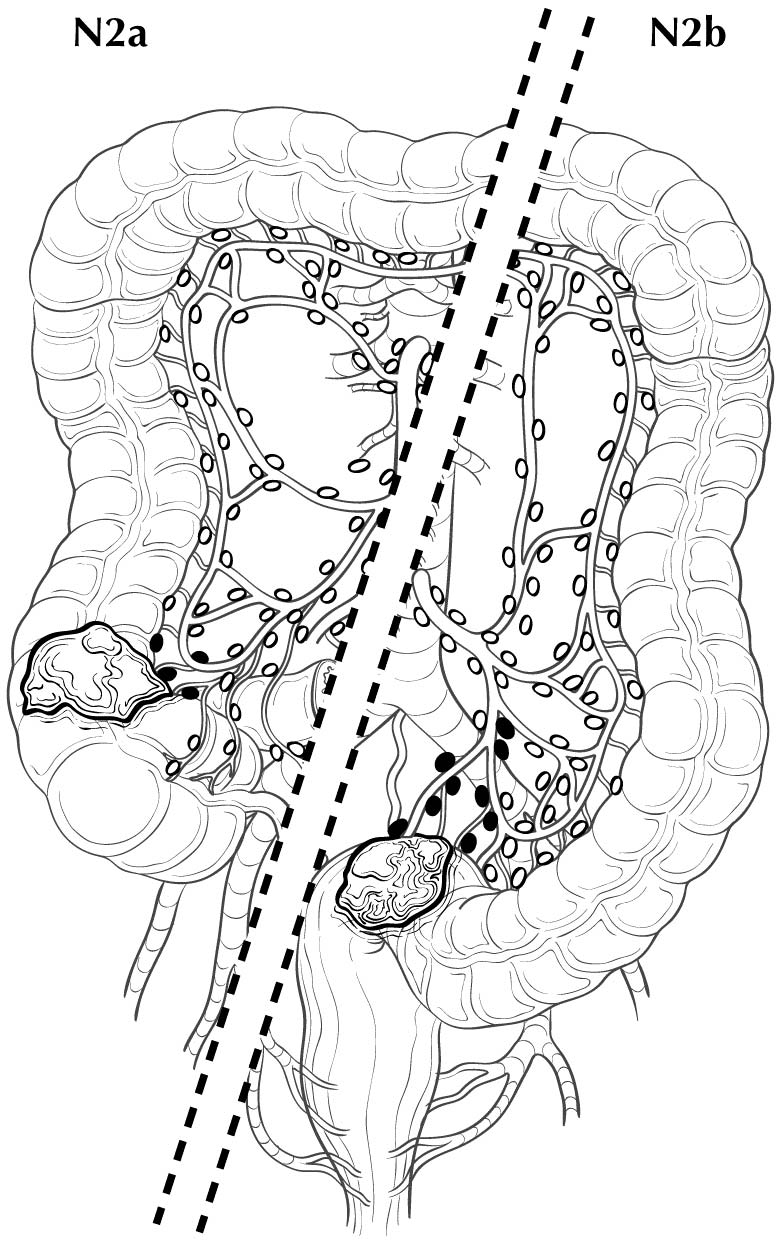

Regional lymph nodes are classified as N1 or N2 according to the number involved by metastatic tumor. Involvement of one to three nodes by metastasis is pN1; involvement of four or more nodes by tumor metastasis is pN2. The number of nodes involved with metastasis influences outcome in both the N1 and N2 groups (Figures 20.5 and 20.6). pN1 is subdivided further into pN1a (metastasis in one regional lymph node) and pN1b (metastasis in two or three regional lymph nodes), and pN2 is subdivided into pN2a (metastasis in four to six regional lymph nodes) and pN2b (metastasis in seven or more regional lymph nodes), because each subgroup represents roughly half the population of N1 or N2, and the subgroups with fewer positive nodes have better survival than those with more positive nodes within the N1 and N2 categories16,17 (Figures 20.6 and 20.7). Lymph nodes outside the regional drainage area of the primary tumor should be categorized as distant metastases; for example, external iliac or common iliac node involvement in a rectosigmoid carcinoma would be M1a.

Controversy exists regarding whether isolated tumor cells or micrometastases in regional nodes are prognostically important. The literature is contradictory because some authors have defined isolated tumor cells as not only individual tumor cells in the subcapsular or marginal sinus but clumps of up to 20 tumor cells.27Micrometastases have been defined as clusters of 10 to 20 tumor cells or clumps of tumor on cut section that measure >=0.2 mm in diameter. These cell clusters indicate that tumor cells have entered a node and replicated and are not merely isolated dormant cells. A recent meta-analysis28 demonstrated that micrometastases, defined as clusters of tumor cells greater than 0.2 mm in diameter, are a significant poor prognostic factor. Lymph nodes harboring such clusters therefore should be considered positive. Although these micrometastases may be designated as N1mi, it may be better to consider these as stand ard positive nodes with the corresponding number, as pathologists likely have considered these to be positive nodes in the past.

In a recent multicenter prospective trial, nearly 200 patients with Stage I or II disease had negative nodes based on stand ard hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining but were found to have tumor cells <0.2 mm in diameter that stained positively with a pan-keratin antibody (N0i+). These patients had a 10% decrease in overall survival compared with patients with N0 disease.29 This decrease in survival occurred in patients with T3-T4 primary tumors but not in those with T1 or T2 primary tumors.29 Further research into N0(i+) detected by pan-keratin staining in otherwise negative H&E-stained lymph nodes may be warranted, especially in patients with T3 or T4 primary carcinomas.

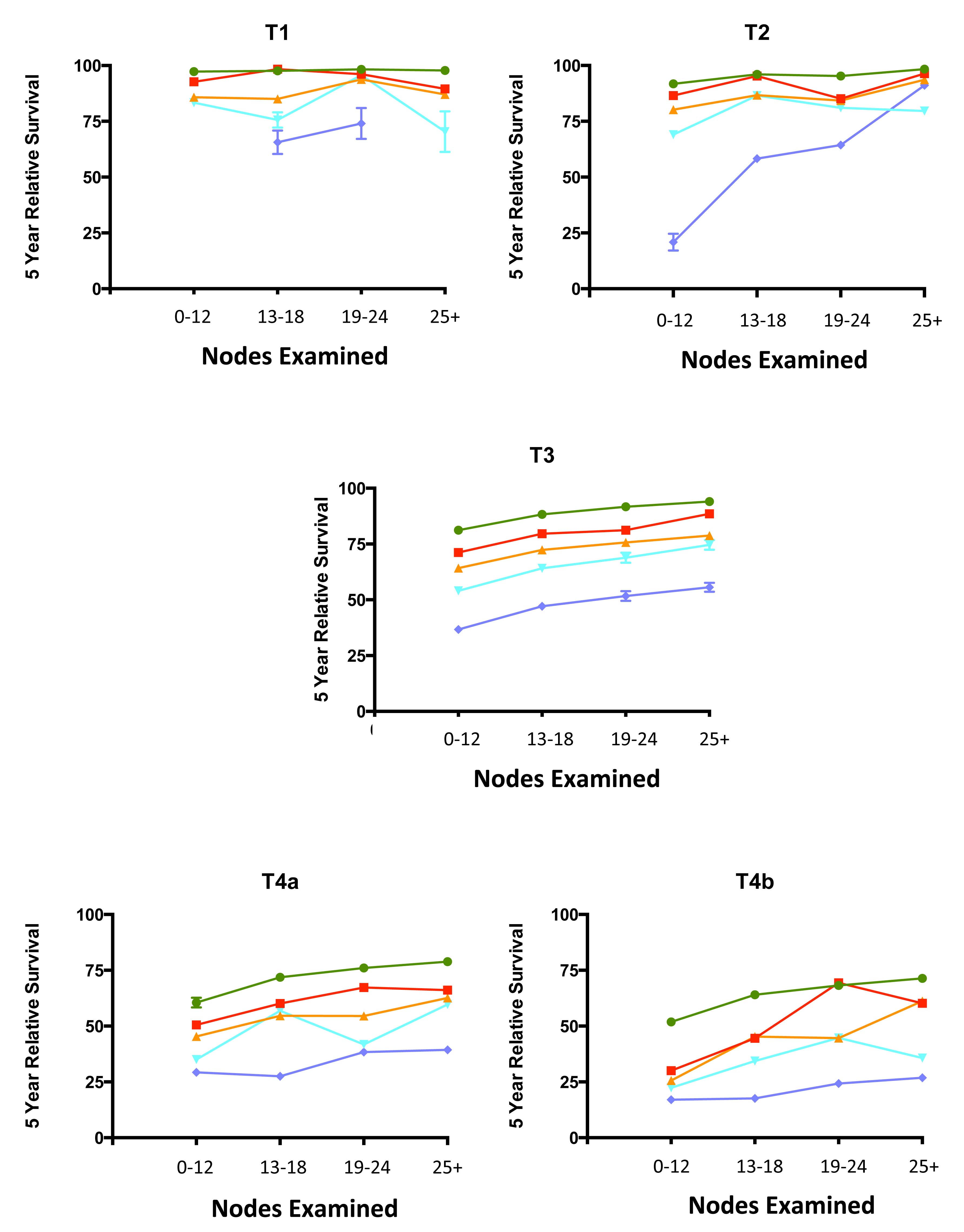

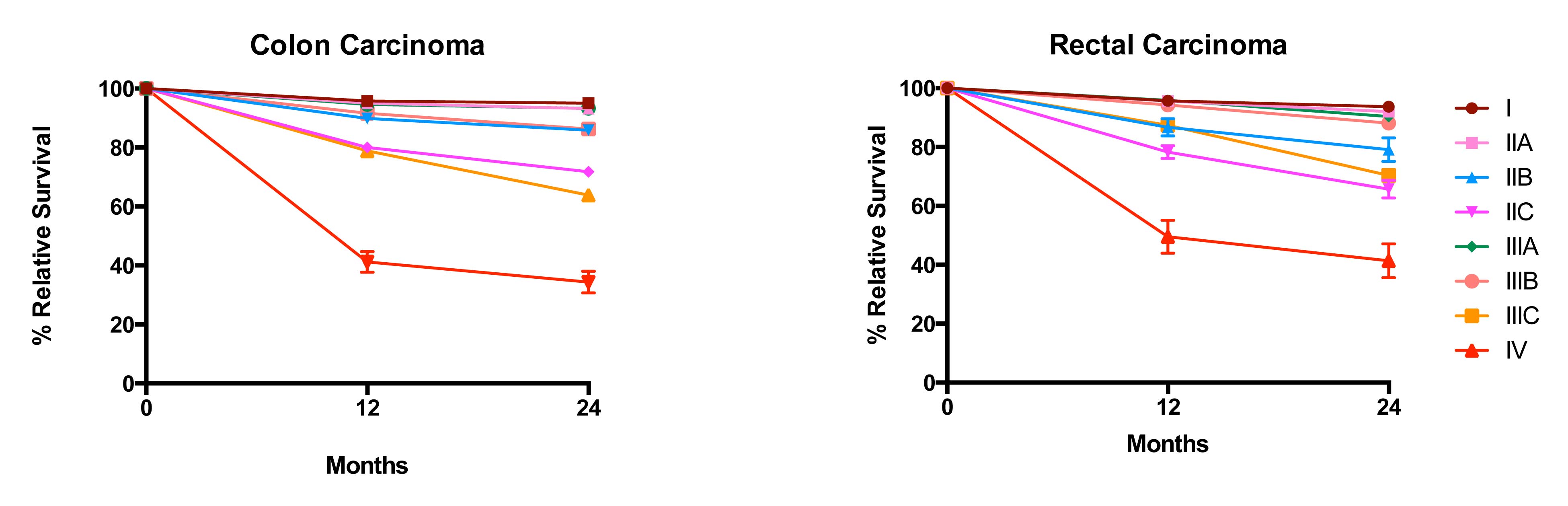

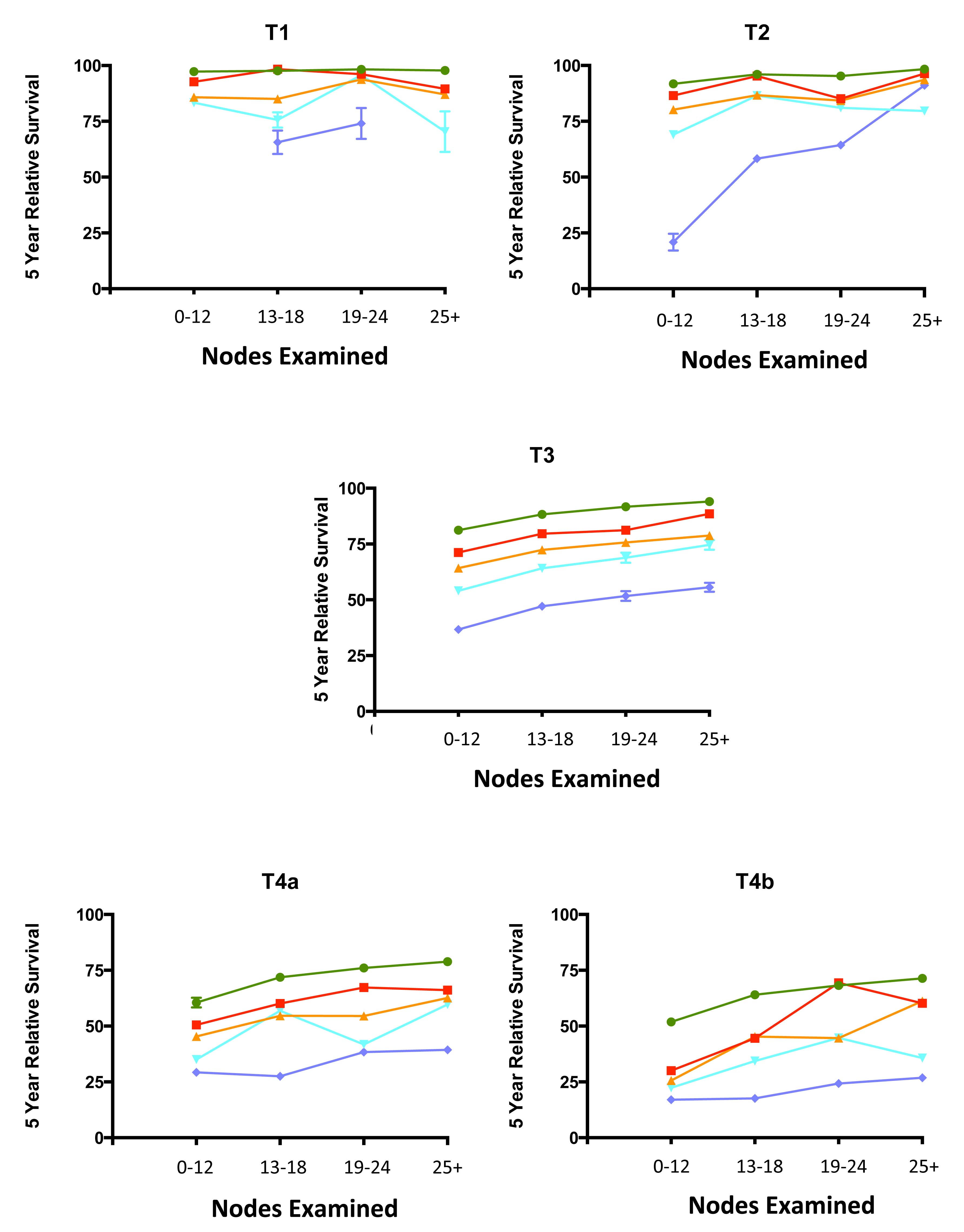

20.6 Impact of positive nodes, the total number of nodes examined, and the depth of primary tumor invasion in a population-based cohort of rectal carcinoma. Data from 30,202 patients diagnosed with rectal carcinoma between 2004 and 2010 and included in the population-based Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database were analyzed for 5-year relative survival. Each T category is presented separately. The N categories are color coded as follows: green, N0 (all nodes negative); red, N1a (one positive node); orange, N1b (two or three positive nodes); light blue, N2a (four to six positive nodes); and dark blue, N2b (seven or more positive nodes). The N1c category is not represented because there is not yet a mature cohort in SEER with 5-year relative survival. The lines for N category levels spread across the numbers of nodes examined. All patients were free of clinical metastases by surgical and clinical staging; that is, they were in stage groups I to III. Results are mean ± SEM of 5-year relative survival except for T4a and T4b, for which the number of patients is small and the error is large. The results suggest that the examination of more nodes for a given N category is associated with increasing survival. N0(i+) and N0mi are not included because they were not recorded previously for colorectal carcinoma.

20.7 Impact of positive nodes, the total number of nodes examined, and the depth of primary tumor invasion in a population-based cohort of colon carcinoma. Data from 144,744 patients diagnosed with colon carcinoma between 2004 and 2011 and included in the population-based SEER database were analyzed for 5-year relative survival. Each T category is presented separately. The N categories are color-coded as follows: green, N0 (all nodes negative); red, N1a (one positive node); orange, N1b (two or three positive nodes); light blue, N2a (four to six positive nodes); and dark blue, N2b (seven or more positive nodes). N1c category is not represented because there is not yet a mature cohort in SEER with 5-year relative survival. The lines for N category levels spread across the numbers of nodes examined. All patients were free of clinical metastases by surgical and clinical staging; that is, they were in stage groups I to III. Results are mean ± SEM of 5-year relative survival. Results suggest that the examination of more nodes for a given N category is associated with increasing survival. N0(i+) and N0mi are not included because they were not recorded previously for colorectal carcinoma.

N1c—Tumor Deposits

Tumor deposits are defined as discrete tumor nodules within the lymph drainage area of the primary carcinoma without identifiable lymph node tissue or identifiable vascular or neural structure. The shape, contour, and size of the deposit are not considered in these designations.

If the vessel wall or its remnant is identifiable on H&E, elastin, or any other stain, the lesion should be classified as lymphovascular invasion (LVI) present (a CAP-required data element). Further documentation should subclassify LVI as small vessel invasion (“L” positive for either lymphatic or small venule involvement) or venous invasion (“V” positive for tumor within an endothelial-lined space that contains red cells or is surrounded by smooth muscle [adapted from the RCPath Colorectal Cancer Dataset 2014]).30 These definitions are similar to those for large vessel invasion on page 122 of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th Edition,14 and LVI is a new data item to be collected. If neural structures are identifiable, the lesion should be classified as perineural invasion.

One to four individual tumor deposits or five or more deposits without involvement of lymphatic, venous, or neural structures within the lymph drainage area of the primary carcinoma should be recorded. In the evaluation of tumors pretreated with radiation and /or chemotherapy, it is important for the pathologist to assess whether tumor nodules represent tumor deposits as defined earlier or discontinuous eradication of the original tumor so that he or she can record the appropriate ypT and ypN categories.

As reported by Quirke, Nagtagaal, and others,31-35 tumor deposits are associated with poor overall survival. A recent population-based study36 demonstrated that approximately 10% of primary colon or rectal carcinomas have tumor deposits and that 2.5% of colon and 3.3% of rectal cases have tumor deposits with otherwise histologically negative lymph nodes. The strength of tumor deposits as a negative prognostic factor in the absence of any nodal metastases resulted in the introduction of the N1c category.

In cases with tumor deposits but no identified lymph node metastases, the N1c category is used and is applicable to all T categories. The presence of tumor deposits does not change the primary tumor T category, but does change the node status (N) to N1c if all regional lymph nodes are pathologically negative. The number of tumor deposits is notadded to the number of positive regional lymph nodes if one or more lymph nodes contain cancer.

Metastasis

Metastasis to only one site/solid organ (e.g., liver, lung, ovaries, nonregional lymph node) should be recorded as M1a. Multiple metastases within only one organ, even if the organ is paired (e.g., the ovaries or lungs), is still M1a disease. Metastases to multiple sites or solid organs distant from the primary site is M1b, excluding peritoneal carcinomatosis. Peritoneal carcinomatosis with or without blood-borne metastasis to visceral organs is designated as M1c, because recent studies suggest that this occurs in 1-4% of patients37,38 and that the prognosis for peritoneal disease is worse than that for visceral metastases to one or more solid organs.39,40 The pathologist should not assign pM0 because M0 is a global designation referring to the absence of detectable metastasis anywhere in the body.

Anastomotic Recurrence

If the tumor recurs at the site of surgery, it is anatomically assigned to the proximal segment of the anastomosis (unless that segment is the small intestine, in which case the colonic or rectal segment should be designated as appropriate) and restaged by the TNM classification. The rprefix is used for the recurrent tumor stage (rTNM).

Colorectal Carcinoma Found at Death

The aprefix is used for cancer discovered as an incidental finding during autopsy and not suspected before death.

Molecular Advances That Will Lead to Future Markers and Therapies

In the past few years, there has been an explosion in the understand ing of the molecular pathology of colorectal carcinoma. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project provided a reference against which alterations that occur in cancer may be compared. The TCGA study in primary colorectal carcinomas41 identified several different pathways that may lead to colorectal carcinoma, including chromosomal instability characterized by truncating mutations in the APCgene; MSI due to loss of function by somatic mutation or promoter hypermethylation of at least one of the DNA MMR genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) with or without POLE mutations and /or the presence of hypermutation; and the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) pathway caused by epigenetic alterations. The various pathways provide several molecular alterations that will create not only prognostic and predictive markers but also opportunities for therapy to be developed in coming years. As stated, hypermutated carcinomas show frequent deficiency in DNA MMR as well as specific mutations associated with this subset.42 Their high rate of somatic mutation may form neoantigens that may induce an antitumor immune response, leading to a better prognosis.43 The emergence of the Immunoscore project, which quantitates host immune infiltrating cells in colorectal carcinoma,44 may be stand ardized in the future. Currently, however, its lack of stand ardization prevents it from being added to TNM staging.

Presently, the only major molecular alterations validated as significant markers with level I evidence are high levels of MSI/defective MMR (MSH-H/dMMR; good prognosis) and mutation in the BRAF gene (poor prognosis). Predictive markers are mutations in KRAS, the related NRAS, and BRAF genes that cause resistance to therapies using monoclonal antibodies to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)45 and possibly to vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA)46 in advanced colorectal carcinoma. The prognostic effects of mutations in the RAS genes appear to be small; this is discussed further in the site-specific factor section. Mutations in the gene PIK3CA47 also may be prognostic and may predict lack of response to therapy against EGFR in advanced colorectal carcinoma, but their level of evidence currently is low.