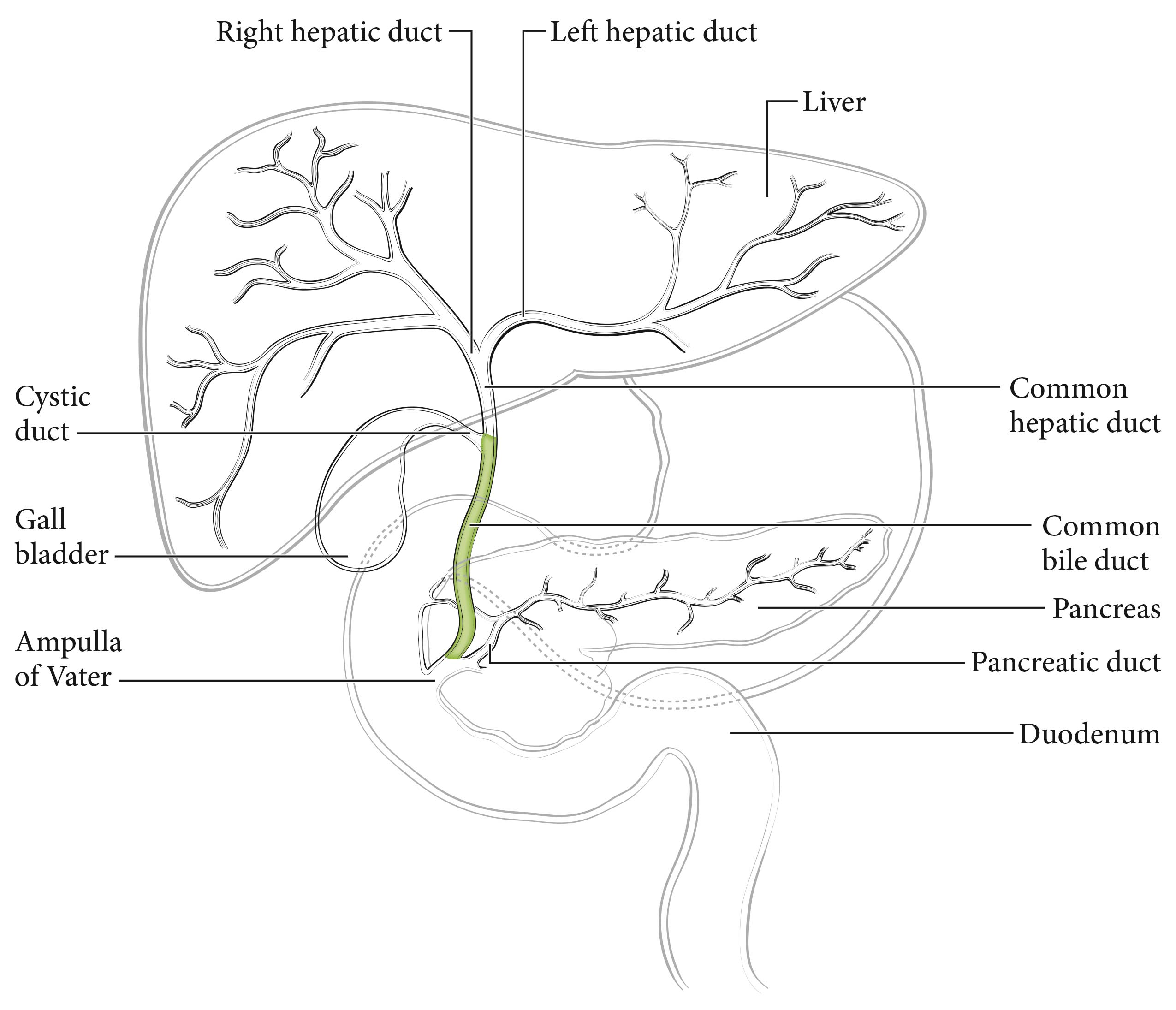

The cystic duct connects to the gallbladder and joins the common hepatic duct to form the common bile duct, which passes posterior to the first part of the duodenum, traverses the head of the pancreas, and then enters the second part of the duodenum through the ampulla of Vater. Tumors with their center located between the confluence of the cystic duct and common hepatic duct and the Ampulla of Vater (excluding ampullary carcinoma) are considered distal bile duct tumors (Figure 34.1). Histologically, the bile ducts are lined by a single layer of tall, uniform columnar calls. The mucosa usually forms irregular pleats or small longitudinal folds. The walls of the bile ducts have a layer of subepithelial connective tissue and muscle fibers. It should be noted that the muscle fibers are most prominent in the distal segment of the common bile duct. The extrahepatic ducts lack a serosa but are surrounded by varying amounts of adventitial adipose tissue. Adipose tissue surrounding the fibromuscular wall is not considered part of the bile duct mural anatomy.

Carcinomas that arise in the distal segment of the common bile duct may spread directly into the pancreas, duodenum, gallbladder, colon, stomach, or omentum.

The regional lymph nodes are the same as those resected for cancers of the head of the pancreas: nodes along the common bile duct and hepatic artery, the posterior and anterior pancreaticoduodenal nodes, and the nodes along the right lateral wall of the superior mesenteric artery.

Most patients with distal bile duct cancer present with biliary symptoms such as painless jaundice and have abnormal liver function tests. Subsequent imaging often detects a biliary obstruction or abnormality. The ideal workup of the stricture includes direct visualization of the bile duct with targeted biopsies. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) may help define the lesion or bile duct wall thickening and may help direct biopsies. Delayed-contrast computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, or MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is used to further assess the lesion, adjacent vessels, and nearby lymph nodes and to detect metastatic disease. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) may allow for bile duct brushings and stenting for unresectable disease. Serologic studies (carcinoembryonic antigen [CEA] and cancer antigen [CA] 19-9) may be considered. Clinical staging also may be based on findings from surgical exploration if the main tumor mass is not resected. The initial surgical assessment should rule out distant metastatic disease and determine local resectability. The presence of a dominant stricture may be a diagnostic feature of distal bile duct cancer. Positive biopsy, cytology, and/or polysomy on fluorescent in situ hybridization confirms the diagnosis.1

Most often, patients are staged following surgery and pathological examination. In one third to half of the cases, surgical resection is not attempted because of local/regional extension, and patients are treated without pathological staging. A single TNM classification applies to both clinical and pathological staging. With advances in imaging, integrated radiologic and pathological staging of patients may be achieved satisfactorily.

Imaging

Cross-sectional imaging, either contrast-enhanced, multiphasic, thin-section MR imaging or CT, typically is the preferred examination for assessing the stage of pancreatic cancers, ampullary tumors, and distal common bile duct tumors and should be performed before any interventions (e.g., biopsy, stent placement). The choice of MR imaging or CT should be based on the imaging equipment available, the expertise of the radiologists performing and interpreting the studies, and whether there are confounding issues, such as allergies to intravenous contrast or renal insufficiency (in the latter case, unenhanced MR imaging is preferred to unenhanced CT because of MR imaging's superior soft tissue contrast). As noted, imaging should be performed before interventions (e.g., stent placement, biopsy) to avoid the effects of potential postprocedure pancreatitis interfering with staging assessments.

If intravenous contrast is used, dynamic imaging (MR or CT) should be performed both during the phase of peak pancreatic enhancement (“pancreatic parenchymal” or “late arterial” phase), to enhance the conspicuity of tumor against the background pancreas (regardless of ampullary, pancreatic, or distal biliary origin), and during the portal venous phase of liver enhancement (peak liver enhancement), when veins are fully opacified, to judge extrapancreatic extent of tumor, involvement of vasculature, and the possibility of liver metastases, as liver metastases from these tumors typically are hypodense against uninvolved liver. Thin-section imaging (e.g., 2-3 mm for CT) is particularly important for judging vascular involvement and to assess for potential small sites of metastatic disease. In the setting of preoperative therapy, this technique is important, not only at baseline but also following therapy, to determine whether patients are still surgical candidates and to follow up borderline suspicious findings.

Endoscopic ultrasound may be used in conjunction with CT/MR imaging to assist in locoregional staging; however, EUS has limited utility in assessing for distant disease such as liver metastases, peritoneal implants, or adenopathy outside the surgical field. EUS and EUS/fine-needle aspiration also should be performed before ERCP, as pancreatitis may degrade the ability of EUS to visualize the tumor and stent placement makes it impossible to identify sites of duct cutoff that may be useful in guiding biopsies. ERCP subsequently may be helpful in the setting of duct abnormalities, both for treatment (stent placement) and for diagnosis (brushings). 2-19

TNM Categories of Staging by Imaging

The relationship of the tumor to relevant vessels should be reported, specifically the relation of the tumor to arteries, such as the superior mesenteric, celiac, splenic, and common hepatic arteries, as well as the aorta if the tumor extends posteriorly into the retroperitoneum. The relationship of the tumor to relevant veins, including the portal vein, splenic vein, splenoportal confluence, and superior mesenteric vein, as well as to branch vessels, such as the gastrocolic trunk, first jejunal vein, and ileocolic branches, also should be recorded.

The relationship of the tumor to the vessels should be described using terms commonly understood by the clinical community, such as degrees of circumferential involvement and the terms abutment (i.e., up to and including 180° of involvement of a given vessel by tumor) and encasement (i.e., greater than 180° of circumferential vessel involvement by tumor). Multiplanar reconstructions for CT and direct multiplanar imaging for MR imaging may be particularly helpful in visualizing the circumferential relationship of the tumor to relevant vasculature. It also is important to describe the relationship of the tumor to adjacent structures such as the stomach, spleen, colon, small bowel, and adrenal glands.

Assessment of N category (nodal) status may be a challenge for all imaging modalities, because preoperative imaging is limited and cannot detect microscopic metastatic disease. Nevertheless, it is important to fully identify the location of visibly suspicious nodes. Nodes are considered suspicious for metastatic involvement if they are greater than 1 cm in short axis or have abnormal morphology (e.g., are rounded, hypodense, or heterogeneous; have irregular margins; involve adjacent vessels or structures). Lymph nodes outside the usual surgical field, such as retroperitoneal nodes, pelvic nodes, and lymph nodes within the jejunal mesentery or ileocolic mesentery, also should be evaluated and reported if abnormal.

The most common sites of metastatic disease include the liver, peritoneum, and lung. Evaluation for potential metastatic disease is best done with contrast-enhanced CT or MR imaging.

Suggested Radiology Report FormatTumor involvement with adjacent vasculature should be reported with terms generally understood by the oncology community, such as degrees of circumferential involvement by tumor of a given vessel, and the terms abutment and encasement, as defined earlier.

The radiology report should include detailed descriptions of the following:

- Primary tumor: location, size, characterization and effect on ducts (common bile duct and main pancreatic duct). Details regarding any findings suspicious for superimposed acute pancreatitis, which may distort findings relevant to staging, or chronic pancreatitis/autoimmune pancreatitis also should be reported, as these diseases may closely mimic malignancy and may be associated with duct strictures.

- Local extent: the relationship of the tumor, with reference to degrees of circumferential involvement using commonly understood terms, such as abutment and encasement, and occlusion with regard to adjacent arterial structures (celiac, superior mesenteric, hepatic, and splenic arteries and the aorta) and venous structures (portal, splenic, and superior mesenteric veins, and if relevant, inferior vena cava). The following observations also should be noted:

- How much of the vascular involvement is related to solid tumor versus stranding, and whether vessel involvement is related to direct involvement by tumor or is separate from the tumor

- Narrowing of vasculature, vascular thrombi, and the length of tumor involvement with the vasculature

- Enlarged collaterals or varices

- Involvement of branch vessels, such as the gastrocolic, first jejunal, and ileocolic branches of the superior mesenteric vein

- Relevant arterial variants: This is particularly important with regard to hepatic arterial variants, such as those arising from the superior mesenteric artery, and the nature of the variant (e.g., accessory right hepatic vs. common hepatic artery arising from the superior mesenteric artery). Confounding factors, such as narrowing of the celiac origin by arcuate ligament syndrome or atherosclerotic disease of the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries, as well as their effects on adjacent vasculature, also are important for treatment planning.

- Lymph node involvement: Suspicious nodes should be documented, particularly those greater than 1 cm in short axis or morphologically abnormal (e.g., rounded nodes, hypodense/heterogeneous/necrotic nodes, nodes with irregular margins); suspicious nodes outside the typical surgical field, such as retroperitoneal, pelvic, and mesenteric nodes, also should be recorded.

- Distant spread: Evaluation of the liver, peritoneum (including whether ascites is present or absent), bone, and lung should be recorded.

- Ascites should be noted, as it may indicate peritoneal metastases.

Pathological staging depends on surgical resection and pathological examination of the specimen and associated lymph nodes. The College of American Pathologists (CAP) Protocol for the Examination of Specimens from Patients with Carcinoma of the Distal Extrahepatic Bile Ducts is recommended as a guideline for the pathological evaluation of resection specimens for distal bile duct cancer (www.cap.org).

As for the T category, assessment of tumor extension may be difficult because the extrahepatic biliary tree lacks uniform smooth muscle distribution along its length, with scattered or no muscle fibers in the wall of the proximal ducts as compared with the distal bile duct.20,21 In addition to the problem created by the lack of discrete tissue boundaries, inflammatory changes in the bile ducts and desmoplastic stromal reaction to tumor may cause distortion of the bile duct wall. To overcome these difficulties, the measurement of tumor depth has been adopted in the new classification.22 This system, however, requires careful perpendicular or longitudinal sectioning of the bile duct so that the deepest tumor invasion (from the basal lamina of adjacent normal or dysplastic epithelium) can be identified and measured. If the depth of invasion is difficult to measure, a best estimate should be given. The level of invasion also should be reported separately (tumor confined to the bile duct, tumor invading beyond the bile duct wall, or tumor extending into an adjacent organ, such as the pancreas, gallbladder, duodenum, or other adjacent organ).

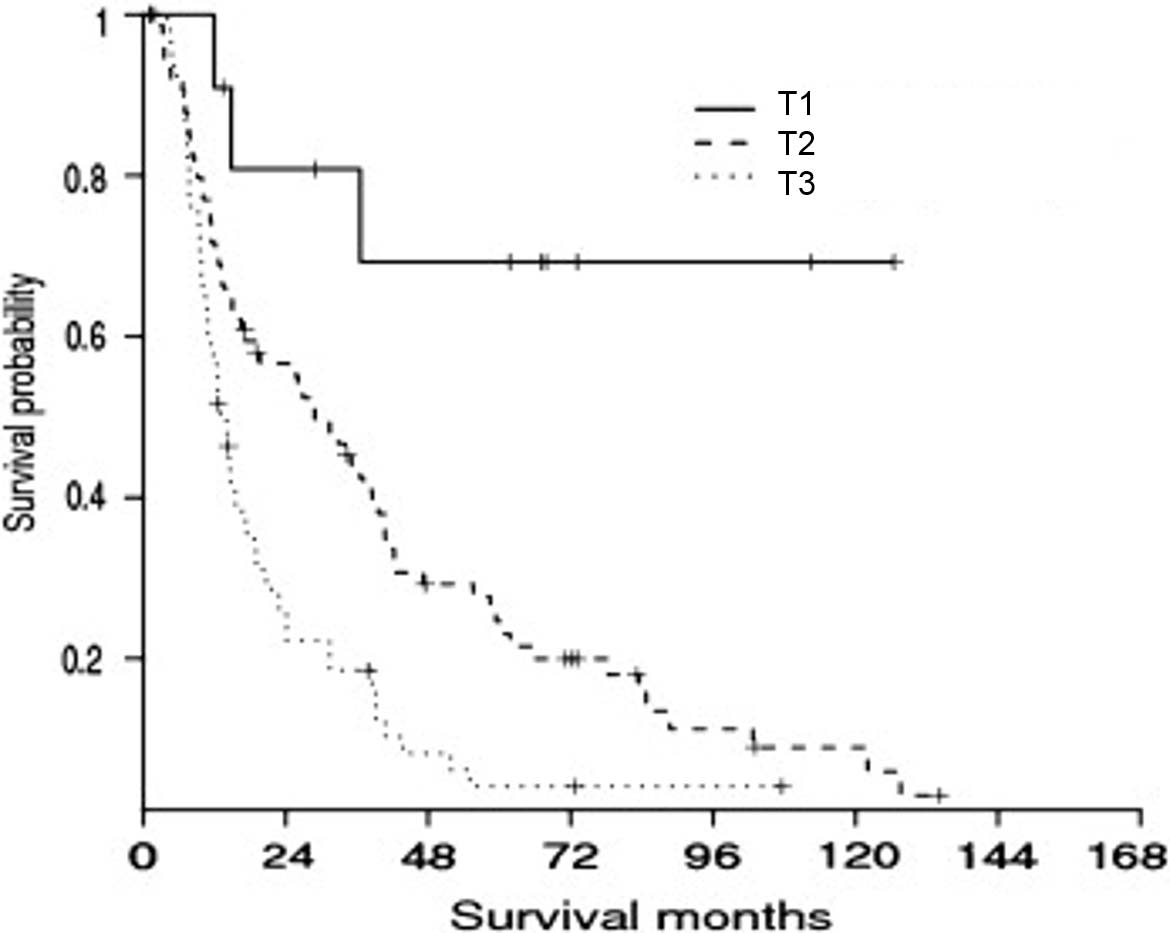

Depth of tumor invasion using the cutoff values of 0.5 cm and 1.2 cm was more powerful than the descriptive extent of tumor invasion in predicting patient outcomes (Figure 34.2) in several single-institution studies.20,22 Tumor depth should be measured from the basement membrane of adjacent normal or dysplastic epithelium to the point of deepest tumor invasion in appropriately oriented and sectioned specimens.22 AJCC Level of Evidence: II

An effort should be made to distinguish a tumor that arises in the intrapancreatic portion of the common bile duct from pancreatic cancer, given the differences in tumor biology, patient outcomes, availability of clinical trials, and staging classifications that apply to each clinical entity. Making this distinction, however, may be challenging because of the intimate association of the bile duct with the pancreas and identical immunophenotypic features.23 Tumors growing symmetrically around the common bile duct are more likely to be distal bile duct carcinomas, whereas an eccentric tumor mass with an epicenter away from the intrapancreatic bile duct more likely is a pancreatic cancer. Another helpful feature that points to distal bile duct origin is the finding of an in situ component, such as prominent biliary intraepithelial neoplasia or a biliary intraductal tubular/tubulopapillary neoplasm.23

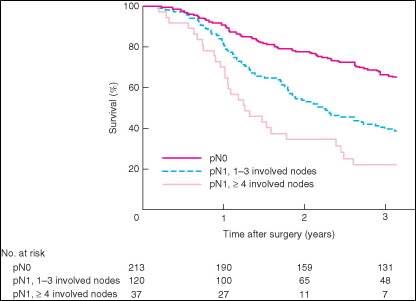

The N category for distal bile duct cancer mirrors that of pancreatic cancer. Specifically, patients are categorized as having no regional lymph node metastasis (N0), metastasis in one to three regional lymph nodes (N1), or metastasis in four or more regional lymph nodes (N2). Tumor involvement of other nodal groups outside the region is considered distant metastasis. Although the minimal number of lymph nodes to be examined for accurate staging has not been determined, examination of at least 12 lymph nodes is recommended.

Accurate pathological staging requires that all lymph nodes that are removed be analyzed. Published studies on optimal histologic examination of a pancreaticoduodenectomy specimen for pancreatic adenocarcinoma support analysis of a minimum of 12 lymph nodes.24 If the resected lymph nodes do not contain metastatic disease but fewer than 12 are retrieved, pN0 should still be assigned. Anatomic division of regional lymph nodes is not necessary; however, separately submitted lymph nodes should be reported as submitted.

The extent of resection (R0, R1, R2) is an important stage-independent prognostic factor and should be reported.25,26 Extrahepatic bile duct carcinomas may be multifocal; thus, microscopic foci of carcinoma or intraepithelial neoplasia may be found at the margin(s) and should be reported.

- Tumor location (ICD code lacks specificity): cystic duct, perihilar bile ducts, or distal bile duct

- CEA

- CA 19-9