Introduction to TNM Staging Classification

Stage may be defined at several time points in the care of the cancer patient. To properly stage a patient's cancer, it is essential to first determine the time point in a patient's care. These points in time are termed classifications and are based on time during the continuum of evaluation and management of the disease. Then, T, N, and M categories are assigned for a particular classification (clinical, pathological, posttherapy, recurrence, and/or autopsy) by using information obtained during the relevant time frame, sometimes also referred to as a staging window. These staging windows are unique to each particular classification and are set forth explicitly in the Supplemental Information. The prognostic stage groups then are assigned using the T, N, and M categories, and sometimes also site-specific prognostic and predictive factors.

Among these classifications, the two predominant are clinical classification (i.e., pretreatment) and pathological classification (i.e., after surgical treatment as initial therapy).

Note C: Rules for Clinical TNM Classification

Clinical stage classification is based on patient history, physical examination, and any imaging done before initiation of treatment. Imaging study information may be used for clinical staging, but clinical stage may be assigned based on whatever information is available. No specific imaging is required to assign a clinical stage for any cancer site. When performed within this framework, biopsy information on regional lymph nodes and/or other sites of metastatic disease may be included in the clinical classification.

See General Staging Rules Table and Stage Classifications Table in Supplemental Information for additional guidance, including the time frame/staging window for determining clinical stage.

Clinical stage is important to record for all patients because:

- clinical stage is essential for selecting initial therapy, and

- clinical stage is critical for comparison across patient cohorts when some have surgery as a component of initial treatment and others do not.

Clinical stage may be the only stage classification by which comparisons can be made across all patients, because not all patients will undergo surgical treatment before other therapy, and response to treatment varies. Differences in primary therapy make comparing groups of patients difficult if that comparison is based on pathological assessment. For example, it is difficult to compare patients treated with primary surgery with those treated with chemotherapy or radiotherapy without surgery or neoadjuvant therapy.

Clinical classification is based on evidence acquired from the date of diagnosis until initiation of primary treatment. Examples of primary treatment include definitive surgery, radiation therapy, systemic therapy, and neoadjuvant radiation and systemic therapy.

Clinical Classification

The clinical stage should be determined before definitive therapy begins, and the clinical stage must not be changed because of subsequent findings once treatment has started; the only exception to this is in early cervical cancer, in which primary surgery can give staging information and at the same time represents the definitive therapy. If there is doubt regarding the stage to which a particular cancer should be assigned, the lesser stage should be selected. This classification applies only to carcinomas, including carcinosarcomas. There should be histologic confirmation of the disease.

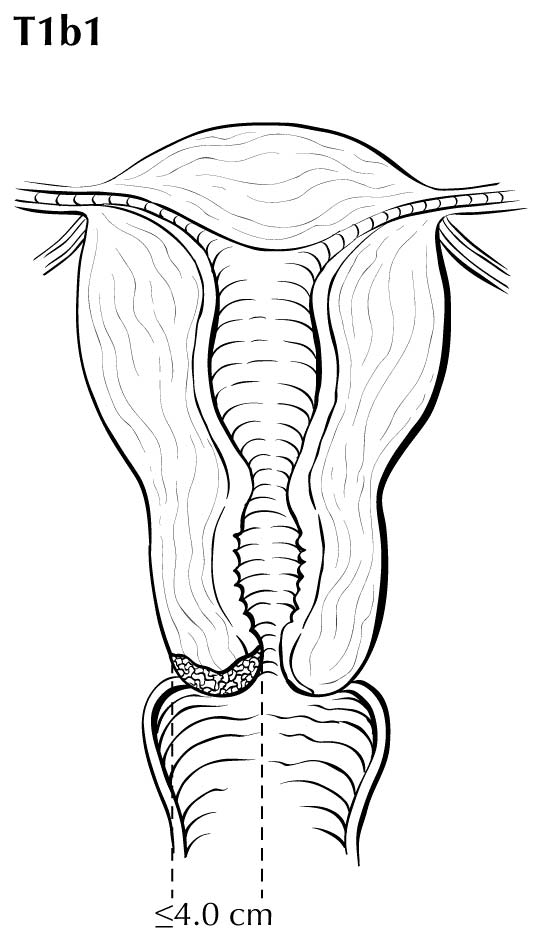

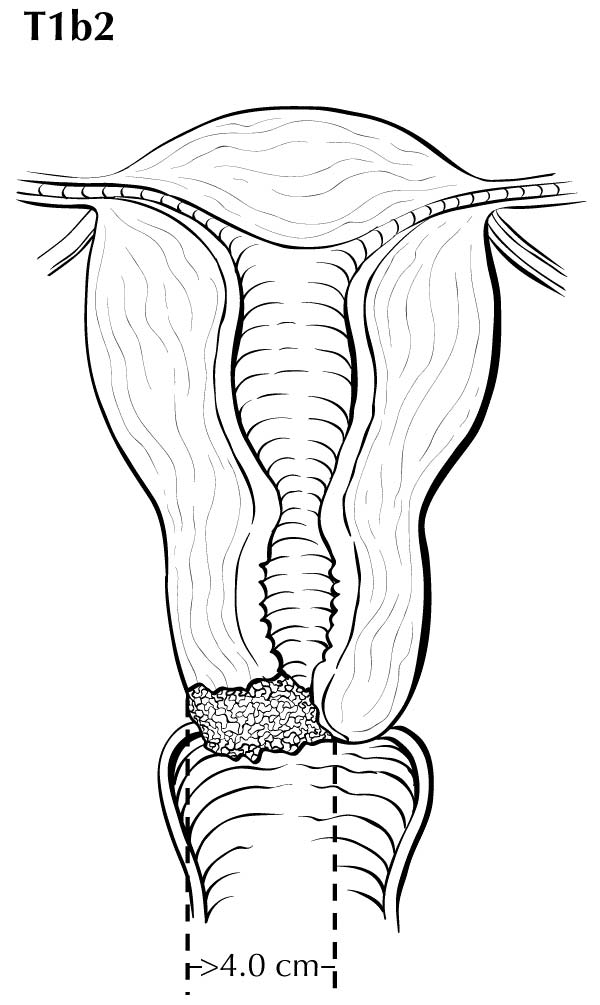

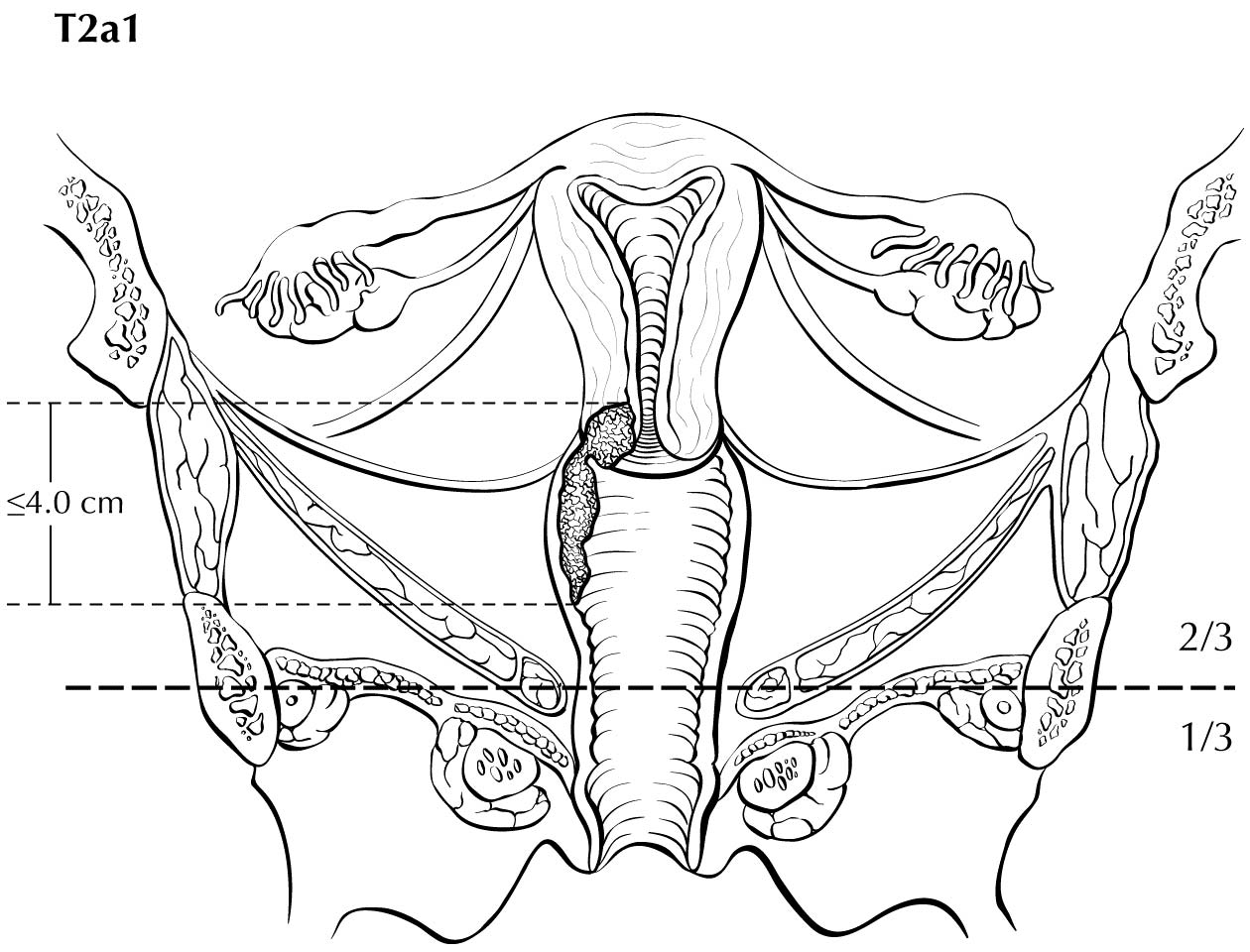

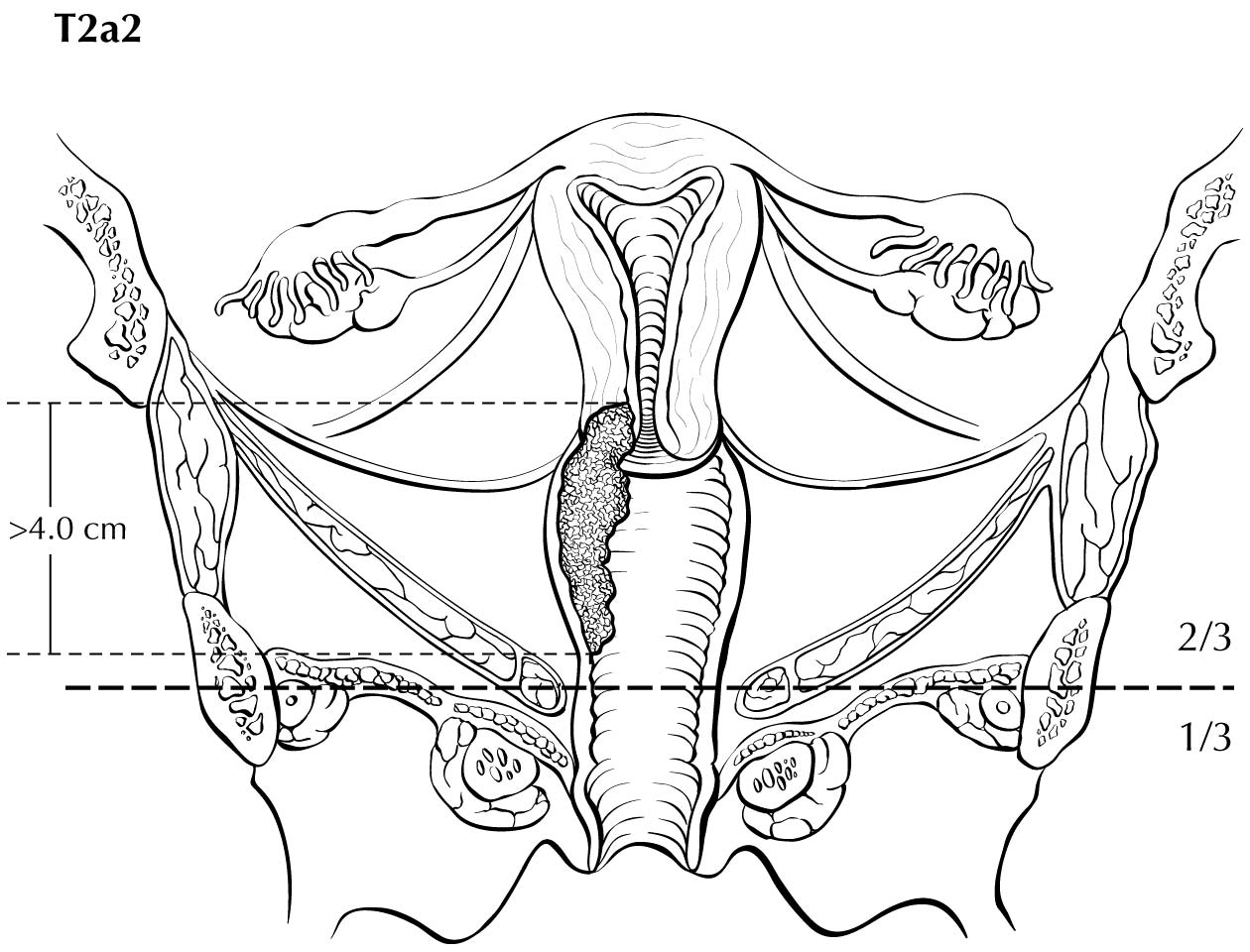

A description of the cervical tumor size is important, especially for stage I and II cancers, for which tumor size has prognostic utility. The 2018 Federation Internationale de Gynecologie et d'Obstetrique (FIGO) staging classification has adopted T subcategories based on tumor size (≤4 cm: T2al; >4 cm: T2a2) for cervical carcinoma spreading beyond the cervix but not to the pelvic wall or lower third of the vagina (T2 lesions).10

Imaging by all modalities may be incorporated into clinical staging. Ultrasonography and roentgenography of the lungs and skeleton are recommended worldwide. If available, CT, MRI, or PET may supplement or replace some of these more traditional tests. PET is usually combined with CT if both tests are available. In clinical practice, selectivity is applied regarding which tests are done even when all these tests are available. If a whole-body PET/CT is done, for example, all other imaging tests except pelvic MRI become unnecessary.

Lymph node status to assign CN may be assessed by surgical means (radiologic-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA], laparoscopic or extraperitoneal biopsy, sentinel node mapping, or lymphadenectomy) or by imaging technologies (CT, MRI, or PET). If the cN is determined by FNA or core biopsy, the (f) suffix is added, for example, cN1a(f). If the cN is determined by a sentinel node procedure, then the (sn) suffix is used. The results of these examinations or procedures may be used to determine clinical staging and to develop a treatment plan and prognostic information. Single tumor cells or small clusters of cells smaller than 0.2 mm in greatest diameter are classified as isolated tumor cells (ITCs). These may be detected by routine histology or by immunohistochemical methods. They are designated as NO(i+) and are not considered nodal metastases.

If nodal metastases are identified, it is important to identify the anatomic location of the involved nodes (pelvic lymph nodes and/or para-aortic lymph nodes) and the methodology by which the diagnosis was established (pathological or radiologic).

Note P: Rules for Pathologic TNM Classification

Classification of T, N, and M after surgical treatment is denoted by use of a lowercase p prefix: pT, pN, and cM0, cM1, or pM1. The purpose of pathological classification is to provide additional precise and objective data for prognosis and outcomes, and to guide subsequent therapy.

Pathological stage classification is based on clinical stage information supplemented/modified by operative findings and pathological evaluation of the resected specimens. This classification is applicable when surgery is performed before initiation of adjuvant radiation or systemic therapy.

See General Staging Rules Table and Stage Classifications Table in Supplemental Information for additional guidance.

Pathological Classification

Cervical excision (cone or loop electrosurgical excision procedure [LEEP]) should be the minimum required to assign staging (pT category) for cervical cancer that is not visible and apparently confined to the cervix. Cervical biopsies or endocervical curettage are not sufficient to determine the T category. Depending on the stage of disease at diagnosis, other suitable surgical treatments to determine the pT category include radical trachelectomy and simple or radical hysterectomy. Pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph node biopsy, sentinel lymph node assessment, or full lymphadenectomy can all be used to determine the pN category.

In surgically treated cases, the pathologist?s findings permit the most accurate measurement of the local extent of disease. These findings should take priority over clinical- or image-based staging and should be used for the pathological staging of disease assigned by the managing physician.

Occasionally, the cancer is incompletely resected with a first procedure, and subsequent resection removes the residual tumor; or the resection is completed in 1 procedure, but there are 2 or more specimens each containing part of the cancer. The pathologist should make an effort to ascertain tumor size from the 2 specimens, realizing that this is an inherently inaccurate method of determining overall tumor size, with expected interobserver variation. Correlation with imaging data may be helpful in such cases.

Pathologists are cautioned that certain prosection techniques may result in measuring the circumference of the tumor instead of the diameter, which in turn will overestimate the size of the tumor if not interpreted in 3-dimensional context.

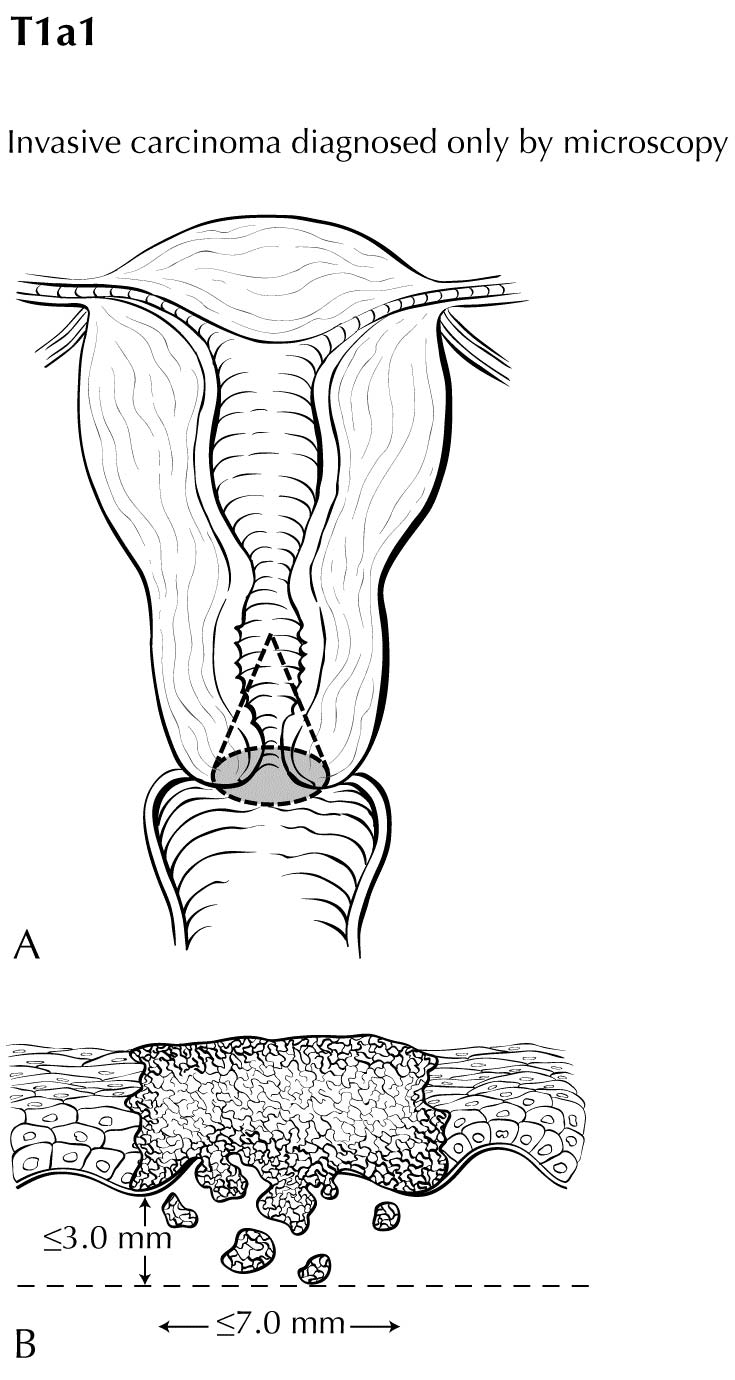

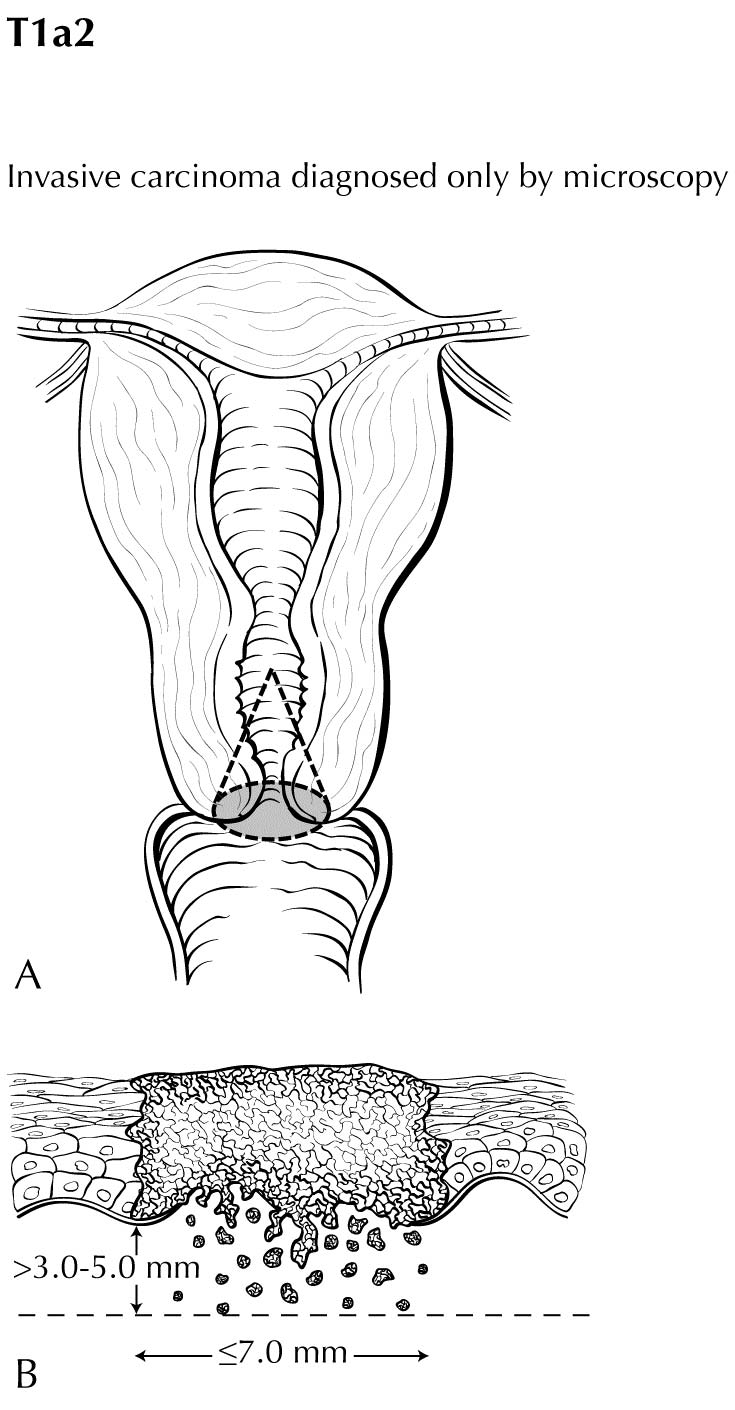

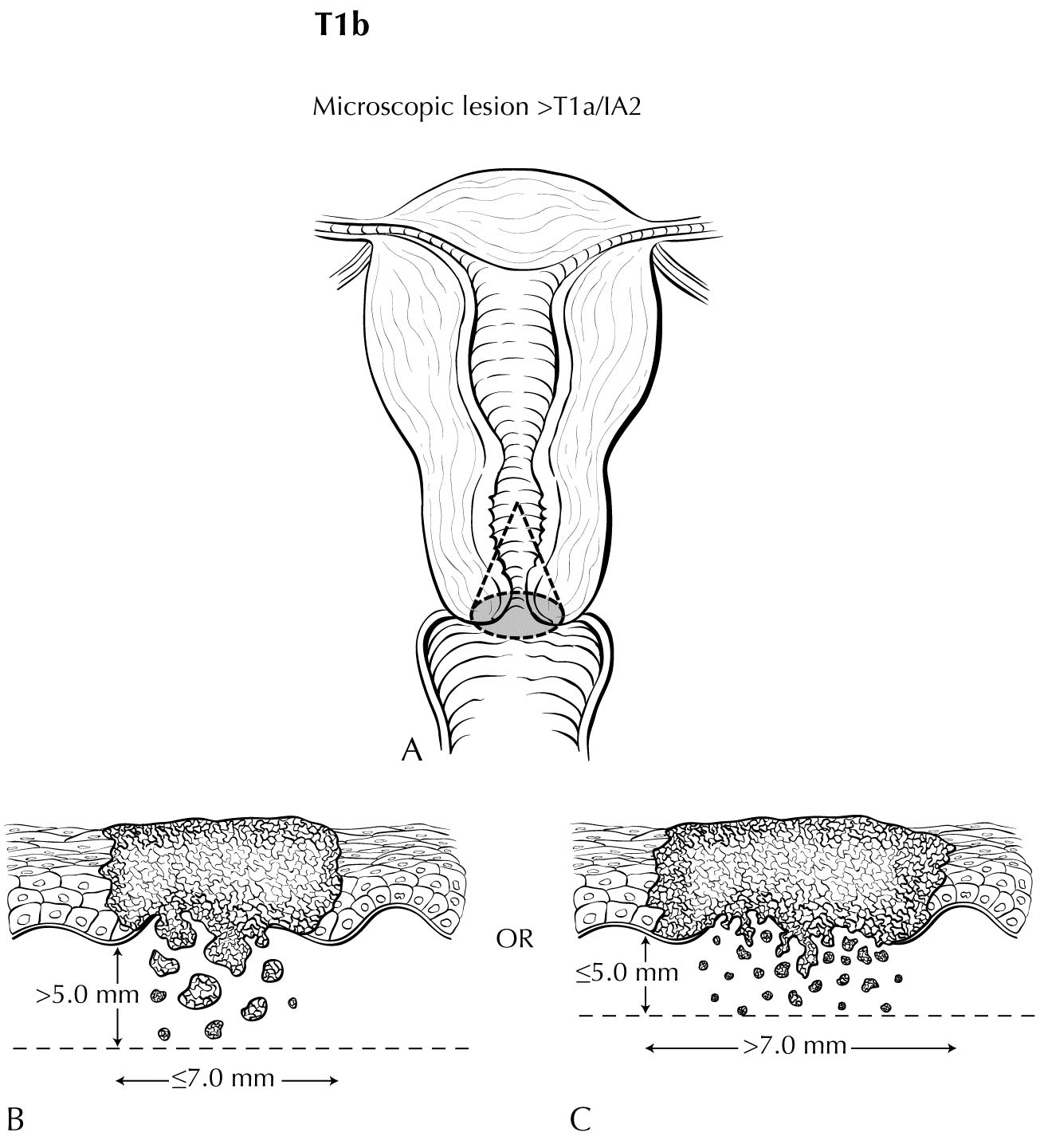

Although staging under AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th edition11 considered horizontal spread for T1a sub-category determination, this information has been dropped in the current staging update. Some stakeholders still feel that horizontal spread may have prognostic significance in early stage cervical cancer. We encourage collection of these data to create an opportunity for future analysis.

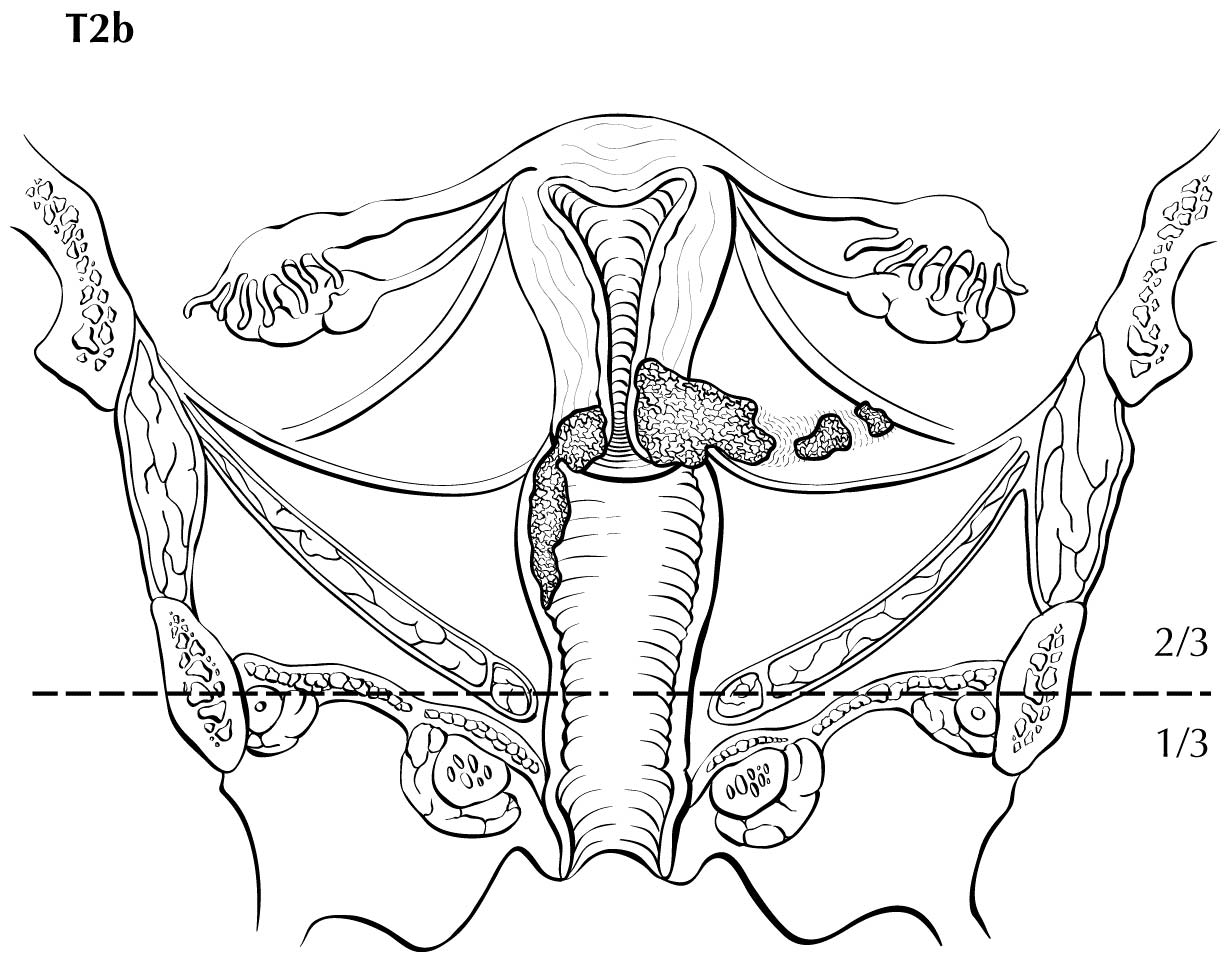

Perineural invasion in the parametrium is sufficient to qualify as pT2b disease and has been reported to be an adverse prognostic feature in a retrospective series.12

Methods of lymph node sampling may include FNA, biopsies, sentinel node procedures, and lymphadenectomy. For TNM staging, the number of resected lymph nodes is immaterial, but the number of resected and positive nodes should be recorded. Pathological classification based on the histologic status of those lymph nodes should be recorded, with the caveat that nodes with ITCs are not considered positive for staging purposes.

MO cannot be assigned pathologically. PM1 requires microscopic confirmation of metastatic disease. Involvement of uterine serosa and adnexa are considered M1 disease. In the absence of clinical or pathological evidence of M1 disease, CMO should be assigned. MX is not a valid category and should not be used.

Note YC: Rules for Posttherapy Clinical TNM Classification

Stage determined after treatment for patients receiving systemic and/or radiation therapy alone or as a component of their initial treatment, or as neoadjuvant therapy before planned surgery, is referred to as posttherapy classification. It also may be referred to as post neoadjuvant therapy classification.

See General Staging Rules Table and Stage Classifications Table in Supplemental Information for additional guidance.

Observed changes between the clinical classification and the posttherapy classification may provide clinicians with information regarding the response to therapy. The clinical extent of response to therapy may guide the scope of planned surgery, and the clinical and pathological extent of response to therapy may provide prognostic information and guide the use of further adjuvant radiation and/or systemic therapy.

Classification of T, N, and M after systemic or radiation treatment intended as definitive therapy is denoted by use of a lowercase yc prefix: yct, ycN, c/pM. The c/pM category may include cMO, CM1, or pM1. The post neoadjuvant therapy assessment of the T and N (YTNM) categories uses specific criteria. In contrast, the M category for post neoadjuvant therapy classification remains the same as that assigned in the clinical stage before initiation of neoadjuvant therapy (e.g., if there is a complete clinical response to therapy in a patient previously categorized as CM1, the M1 category is used for final yc and yp staging).

See Stage Classifications Table in Supplemental Information for additional guidance.

Note YP: Rules for Posttherapy Pathological TNM Classification

Classification of T, N, and M after systemic or radiation neoadjuvant treatment followed by surgery is denoted by use of a lowercase yp prefix:ypt, ypN, c/PM. The c/PM category may include cMO, MI, or PM1. The post neoadjuvant therapy assessment of the T and N (yTNM) categories uses specific criteria. In contrast, the M category for post neoadjuvant therapy classification remains the same as that assigned in the clinical stage before initiation of neoadjuvant therapy (e.g., if there is a complete clinical response to therapy in a patient previously categorized as CM1, the M1 category is used for final yc and yp staging).

The time frame for assignment of ypT and ypN should be such that the post neoadjuvant therapy surgery and staging occur within a period that accommodates disease-specific circumstances.

Criteria: First therapy is systemic and/or radiation therapy followed by surgery.y-pathological (yp) classification is based on the:

- y-clinical stage information, and supplemented/modified by

- operative findings, and

- pathological evaluation of the resected specimen.

Examples of treatments that satisfy the definition of neoadjuvant therapy for cervix may be found in sources such as the NCCN Guidelines, ASCO guidelines, or other treatment guidelines. Systemic therapy includes chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and immunotherapy. Not all medications given to a patient meet the criteria for neoadjuvant therapy (e.g., a short course of therapy that is provided for variable and often unconventional reasons, should not be categorized as neoadjuvant therapy).

See Stage Classifications Table in Supplemental Information for additional guidance.

Note R: Rules for Recurrence/Retreatment TNM Classification

Staging classifications at the time of retreatment for a recurrence or disease progression is referred to as recurrence classification. It also may be referred to as retreatment classification. Classification of T, N, and M for recurrence or retreatment is denoted by use of the lowercase r prefix: rct, reN, rc/rpM, and rpT, rpN, rc/rpM. The rc/rpM may include rcMO, rcM1, or rpMI.

See Stage Classifications Table in Supplemental Information for additional guidance.

Note A: Rules for Autopsy TNM Classification

Staging classification for cancers identified only at autopsy is referred to as autopsy classification. This classification is used when cancer is diagnosed at autopsy and there was no prior suspicion or evidence of cancer before death. All clinical and pathological information obtained at the time of death and through post-mortem examination is included. Classification of T, N, and M at autopsy is denoted by use of the lowercase a prefix: aT, aN, aM.

See Stage Classifications Table in Supplemental Information for additional guidance.

Note CE: Clinical Examination

Careful clinical examination should be performed in all cases, preferably by an experienced examiner and with the patient under anesthesia. Examination under anesthesia (EUA) allows the clinician to optimally visualize and palpate the tumor without subjecting the patient to undue discomfort. EUA is typically coupled with colposcopy, cystourethroscopy, rigid proctoscopy, and biopsies of the primary tumor and suspected mucosal surfaces.

Note I: Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is currently the preferred modality for local assessment of cervical cancer.13 Contrast-enhanced CT does not have the soft-tissue resolution necessary to evaluate the local extent of the tumor and may not be helpful in assessing early disease, specifically in patients who want to undergo fertility-preserving surgery.

Determination of lymph node metastases on cross-sectional imaging is based on lymph node size, with abnormal being >1 cm in the short axial dimension. Hybrid PET/CT also may be used to determine lymph node status in patients who have locally advanced cancer. Metabolically active lymph nodes of any size on PET/CT are considered metastatic, unless there is another known cause for metabolic activity. PET/CT is considered superior to other modalities in evaluating for extrapelvic disease and bone metastases.

MRI

MRI has excellent soft-tissue contrast resolution. Intravaginal gel is recommended prior to imaging of the pelvis in the setting of cervical cancer staging evaluation. The vaginal gel helps distend the vagina, provides better assessment of tumor extension to the vagina, and may help guide radiation treatment planning. A prospective multicenter trial in patients with early-stage cervical cancer showed a sensitivity of 53% for MRI versus 29% for clinical examination to help detect parametrial extension.14

MRI is superior to CT scans or clinical examinations owing to its superior soft-tissue resolution in determining tumor size (measured as the largest diameter of the tumor in the axial plane or the craniocaudal dimension), as well as in assessing the tumor's local relationship with the surrounding structures.15-18

Stage IB disease can be detected on MRI with a sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 98%. Tumors <1 cm can be detected on dynamic contrast-enhanced and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI).19-21

With its better soft-tissue resolution, MRI has a sensitivity of 90% to 98% in the detection of internal os involvement.13,22,23 It is specifically useful in patients undergoing trachelectomy. However, MRI has limited ability to assess postbiopsy inflammatory changes because postbiopsy changes may appear as focal areas of enhancement, which can be mistaken as tumor. This limitation can be overcome by correlating with the diffusion-weighted sequence along with apparent diffusion coefficient maps, which have been able to to differentiate the 2 entities.

Despite these advances with MRI techniques, stage IA disease may not be visible on MRI because it is microscopic and can be better assessed on pathology. MRI has the ability to clearly define the tumor's relationship with the surrounding structures. It can assess vaginal involvement with an accuracy of 86% to 93%.22,24,25 It is particularly useful when assessment of the vaginal apex may be difficult on physical examination owing to pelvic pain or agglutination.

Disruption of the cervical stroma on MRI suggests parametrial extension, and this can increase the T category from T2a to T2b. However, microscopic invasion of the parametrium may not be visible on imaging and may result in false-negative findings, whereas inflammation surrounding the tumor may yield a false-positive finding. One study has shown that MRI accompanied by clinical examination increases sensitivity for parametrial invasion and helps select surgical candidates with a higher accuracy.22

Soft-tissue extension from the tumor to the adjacent organs as seen on MRI has a 100% reported accuracy in assessing involvement of the rectum22 or bladder invasion and thus can reliably exclude category T4 disease. This can be assessed on postcontrast T1-weighted imaging or the T2-weighted nonfat saturated sequence.

MRI has a specificity of 96.8% and a low sensitivity of 50% for pelvic nodal metastasis versus 66.6% and 100%, respectively, for para-aortic nodal metastasis.22,27-30 The low sensitivity may reflect the fact that tumor-involved lymph nodes are mostly detected by their size on imaging, which may appear normal in the early metastatic process. The cutoff value used to predict pathologic lymph nodes on imaging is 0.8 to 1.0 cm in the short axis. However, the sensitivity of MRI increases when detecting lymph node metastasis in bulky cervical tumors. A recent meta-analysis by Shen et al31 found that DWI imaging may improve detection of metastatic lymph nodes as the reported pooled sensitivity and specificity of DWI for assessment of metastatic lymph nodes were 86% and 84%, respectively.

PET/CT

PET/CT is limited in evaluating primary tumor size as well as parametrial involvement, internal os involvement, and soft-tissue invasion of the vagina and adjacent organs.32,33 PET/CT can assess metabolic activity in the tumor,26 making the tumor conspicuous; however, it is not able to identify microscopic disease. Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) activity in the bladder can obscure adjacent organ involvement, specifically, bladder involvement.

PET/CT has a higher ability to detect metastatic lymph nodes compared with MRI,34 because metastatic lymph nodes may be metabolically active even when they may morphologically show a normal size. One PET study35 showed a positive and negative predictive value of 91% and 85%, respectively, and an overall accuracy of 88% for pelvic lymph nodes. Benign inflammatory lymph nodes, however, can be metabolically active, and this may limit the accuracy of PET/CT. PET/CT performs better in assessing lymph nodes in late-T category disease,36,37 with a sensitivity and specificity of 75% and 95%, respectively, compared with 53% to 73% and 90% to 97%, respectively, in early-stage disease.38,39 PET has also been shown to alter management in up to 28% of patients36,37 by detecting extrapelvic disease and can be used as a one-stop shop for suspected metastases, specifically in bulky tumors.

CT Scan

Although CT is widely available, it has limited value in the detection and local staging of cervical cancer owing to its poor soft-tissue resolution. Small cervical tumors may have similar attenuation to the cervix and may be invisible; large cervical tumors may appear as an enlarged cervix.40

CT has a lower accuracy of 72% compared with 95% accuracy of MRI for assessment of parametrial invasion.41,42 The overall reported accuracy of CT in assessing bladder invasion ranges between 96% and 98%,43-46 especially in bulky disease.

The reported accuracy of CT in detecting lymph node metastases ranges from 37% to 86%.37,47 Similar to MRI, size criteria are used with CT for detection of metastatic lymph nodes.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is a widely available, noninvasive imaging modality and is available at a lower cost than other imaging technologies.

Fischerova et al48 found that transrectal ultrasound is able to detect cervical cancer with a sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 93%, 95%, and 94%, respectively. However, transrectal ultrasound is not performed in routine practice. A European multicenter study found that ultrasound detected cervical cancer at a rate of 97% with a specificity of 90% compared with the rates for MRI of 90% and 67%, respectively.49 Ultrasound is operator dependent, has high interobserver variability, and depends on the patient's body habitus. Ultrasound is limited in detection of distant enlarged lymph nodes. Testa et als50 found that ultrasound failed to detect 91% of lymph node metastasis owing to its small field of view. In a study by Epstein et al,49 ultrasound detected only 3 of 38 lymph node metastases. Retroperitoneal lymph nodes may be difficult to detect, specifically in obese patients and in the presence of bowel gas.

PET/MRI

PET/MRI is a promising new modality that combines the advantage of local staging by MRI and nodal detection by PET. PET/MRI has a sensitivity and specificity of 91% and 94%, respectively, for lymph node detection.51 It has the ability to locally stage a patient's tumor owing to the superior soft-tissue resolution of MRI. More studies will be needed to assess the staging efficacy and cost-effectiveness of this powerful new tool.

Contribution of Imaging to TNM Staging

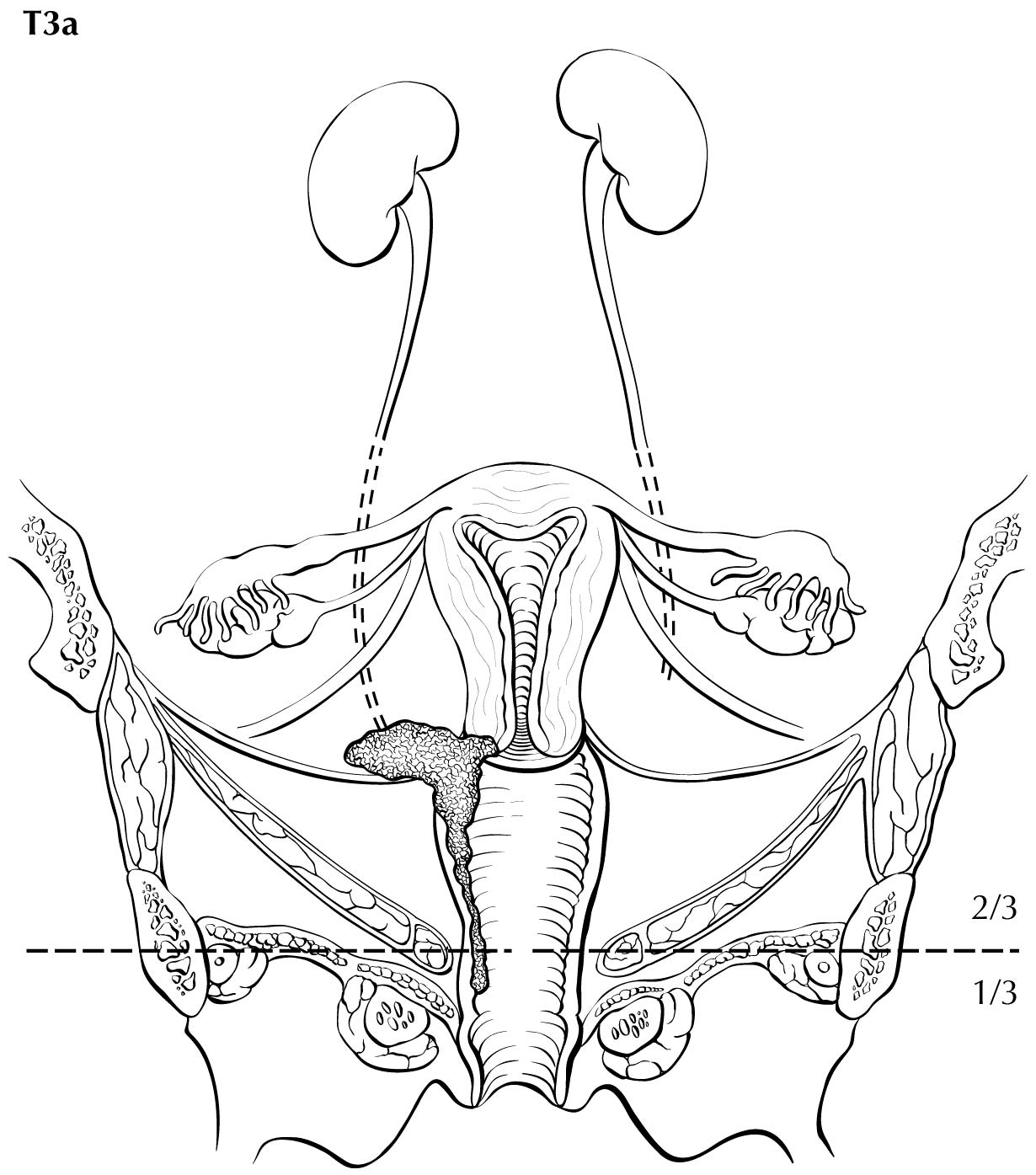

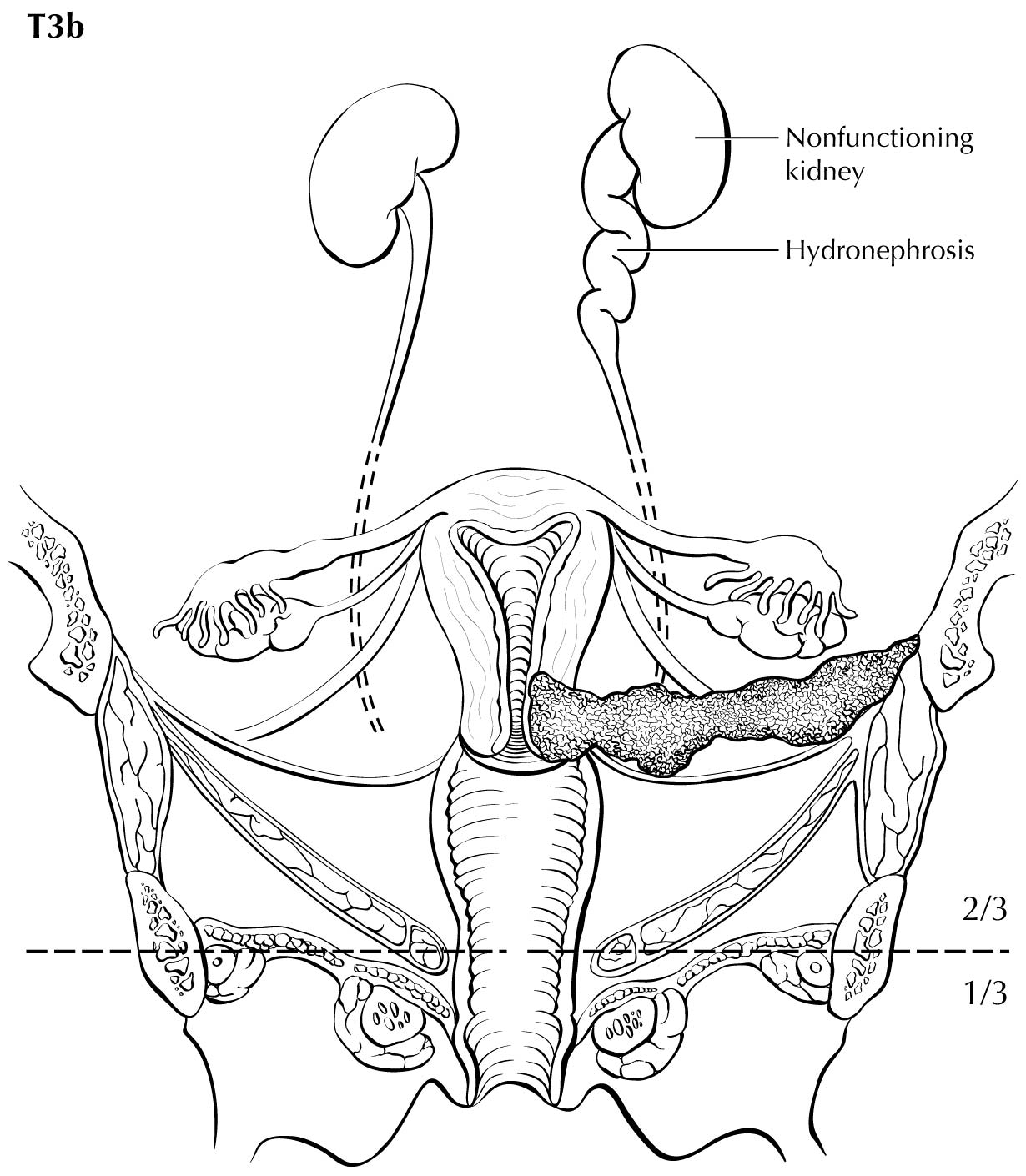

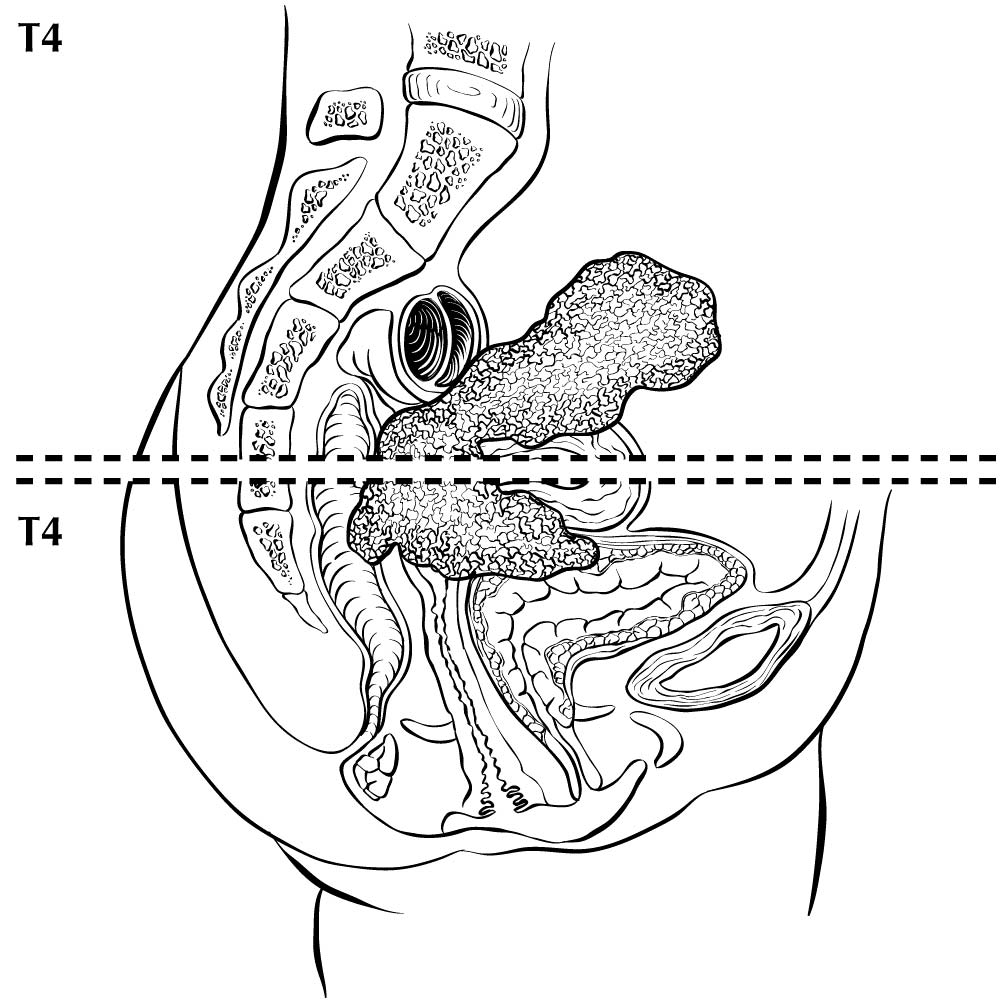

Category T1a disease is not seen on imaging. Although invasion may be suspected on the basis of imaging, the depth of invasion cannot be assessed with a level of certainty appropriate for clinical use, and the use of imaging, including MRI, for this purpose is discouraged. In T1b disease, the tumor is visible on imaging, and the T (ie, size) category is assessed by measuring the greatest diameter of the tumor in any plane, on the sequence in which it is most conspicuous. T2a disease involves the upper two-thirds of the vagina, which is visible on MRI. Another important assessment typically made by MRI is parametrial involvement, which can determine the primary modality of therapy in apparently early cervical cancer. When the tumor causes hydronephrosis or extends to the pelvic wall, it is considered to be clinical category T3b. Involvement of adjacent organs is considered to be category T4; however, the presence of bullous edema on the bladder mucosa is not considered true bladder involvement and does not represent T4 disease.

When there is discordance between imaging and clinical examination, and before surgical resection or if surgical resection is not done, the ct category should be based on imaging measurement of size, which is typically more accurate than clinically estimated size.

Regional nodal metastases are considered N1 or N2 disease and may be assessed on CT and MRI. This classification is based on the criterion for abnormal size of >1 cm in the short axial dimension. However, metabolically active lymph nodes of any size on FDG PET scans are considered metastatic.

The presence of involved lymph nodes beyond the pelvis or para-aortic region, or bone metastases, is considered MI disease, and PET/CT is considered the best modality to assess for this. If PET/CT is not available, contrast-enhanced CT may be used. In low-resource settings, a total body bone scan may be used to survey for skeletal metastases.

Suggested Imaging Report Format

- Primary tumor

- Size (diameter in the axial and the craniocaudal dimension)

- Local extent

- Involvement of the internal os and distance from the internal os

- Depth of cervical invasion (in mm)

- Involvement of the vagina (upper third, middle third, and lower third)

- Parametrial extension, with presence or absence of hydronephrosis

- Involvement of the bladder and rectum/adjacent bowel loops

- Adenopathy

- Regional (pelvic and para-aortic)

- Distant lymph node: inguinal, mediastinal, and supraclavicular

- Extrapelvic disease

- Distant organ involvement

- Liver, peritoneum, lungs, and other organs

- Bone involvement

General Staging Rules

| Topic | Rules |

| Microscopic confirmation |

Example: Lung cancer diagnosed by CT scan only, that is, without a confirmatory biopsy |

| Time frame/staging window for determining clinical stage | Information gathered about the extent of the cancer is part of clinical classification:

|

| Time frame/staging window for determining pathological stage | Information including clinical staging data and information from surgical resection and examination of the resected specimens - if surgery is performed before the initiation of radiation and/or systemic therapy - from the date of diagnosis:

|

| Time frame/staging window for staging post neoadjuvant therapy or posttherapy | After completion of neoadjuvant therapy, patients should be staged as:

|

| Progression of disease | If there is documented progression of cancer before therapy or surgery, only information obtained before the documented progression is used for clinical and pathological staging.

Progression does not include growth during the time needed for the diagnostic workup, but rather a major change in clinical status. Determination of progression is based on managing physician judgment, and may result in a major change in the treatment plan. |

| Uncertainty among T, N, or M categories, and/or stage groups: rules for clinical decision making | If uncertainty exists regarding how to assign a category, subcategory, or stage group, the lower of the two possible categories, subcategories, or groups is assigned for

Note: Unknown or missing information for T, N, M or stage group is never assigned the lower category, subcategory, or group. |

| Uncertainty rules do not apply to cancer registry data | If information is not available to the cancer registrar for documentation of a subcategory, the main (umbrella) category should be assigned (e.g., TI for a breast cancer described as <2 cm in place of T1a, T1b, or T1c). If the specific information to assign the stage group is not available to the cancer registrar (including subcategories or missing prognostic factor categories), the stage group should not be assigned but should be documented as unknown. |

| Prognostic factor category information is unavailable | If a required prognostic factor category is unavailable, the category used to assign the stage group is:

|

| Grade | The recommended histologic grading system for each disease site and/or cancer type, if applicable, is specified in each disease site and should be used by the pathologist to assign grade.

The cancer registrar will document grade for a specific site according to the coding structure in the relevant disease site. |

| Synchronous primary tumors in a single organ: (m) suffix | If multiple tumors of the same histology are present in one organ:

|

| Synchronous primary tumors in paired organs | Cancers occurring at the same time in each of paired organs are staged as separate cancers. Examples include breast, lung, and kidney. Exception: For tumors of the thyroid, liver, and ovary, multiplicity is a T-category criterion, thus multiple synchronous tumors are not staged independently. |

| Metachronous primary tumors | Second or subsequent primary cancers occurring in the same organ or in different organs outside the staging window are staged independently and are known as metachronous primary tumors.

Such cancers are not staged using the y prefix. |

| Unknown primary or no evidence of primary tumor | If there is no evidence of a primary tumor, or the site of the primary tumor is unknown, staging may be based on the clinical suspicion of the organ site of the primary tumor, with the tumor categorized as TO. The rules for staging cancers categorized as TO are specified in the relevant disease sites. Example: An axillary lymph node with an adenocarcinoma in a woman, suspected clinically to be from the breast, may be categorized as TO N1 (or N2 or N3) MO and assigned Stage II (or Stage III). Examples of exception: The TO category is not used for head and neck squamous cancer sites, as such patients with an involved lymph node are staged as unknown primary cancers using the "Cervical Nodes and Unknown Primary Tumors of the Head and Neck" system (TO remains a valid category for human papillomavirus (HPV)- and Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]-associated oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal cancers). |

| Date of diagnosis | It is important to document the date of diagnosis, because this information is used for survival calculations and time periods for staging. The date of diagnosis is the date a physician determines the patient has cancer. It may be the date of a diagnostic biopsy or other microscopic confirmation or of clear evidence on imaging. This rule varies by disease site and shares similarities with the earlier discussion on microscopic confirmation. |

Stage Classifications

Stage classifications are determined according to the point in time of the patient's care in relation to diagnosis and treatment. The five stage classifications are clinical, pathological, posttherapy/post neoadjuvant therapy, recurrence/ retreatment, and autopsy.

| Classification | Designation | Details |

| Clinical | cTNM or TNM | Criteria: used for all patients with cancer identified before treatmentIt is composed of diagnostic workup information, until first treatment, including:

Note: Exceptions exist by site, such as complete excision of primary tumor for melanoma. |

| Pathological | pTNM | Criteria: used for patients if surgery is the first definitive therapy

It is composed of infor from:

|

| Posttherapy or post neoadjuvant therapy | ycTNM and ypTNM | For purposes of posttherapy or post neoadjuvant therapy, neoadjuvant therapy is defined as systemic and/or radiation therapy given before surgery: primary radiation and/or systemic therapy is treatment given as definitive therapy without surgery.

ycThe yc classification is used for staging after primary systemic and/or radiation therapy, or after neoadjuvant therapy and before planned surgeryCriteria: First therapy is systemic and/or radiation therapy. ypThe yp classification is used for staging after neoadjuvant therapy and planned post neoadjuvant therapy surgery. Criteria: First therapy is systemic and/or radiation therapy and is followed by surgery. |

| Recurrence or retreatment | rTNM | This classification is used for assigning stage at time of recurrence or progression until treatment is initiated.

Criteria: Disease recurrence after disease-free interval or upon disease progression if further treatment is planned for a cancer that:

rcClinical recurrence staging is assigned as rc. rpPathological staging information is assigned as rp for the rTNM staging classification. This classification is recorded in addition to and does not replace the original previously assigned clinical (c), pathological (p), and/or posttherapy (yc, yp) stage classifications, and these previously documented classifications are not changed. |

| Autopsy | aTNM | This classification is used for cancers not previously recognized that are found as an incidental finding at autopsy, and not suspected before death (i.e., this classification does not apply if an autopsy is performed in a patient with a previously diagnosed cancer).

Criteria: No cancer suspected prior to death Both clinical and pathological staging information is used to assign a TNM. |

Note S: Identification of Primary Site(s)

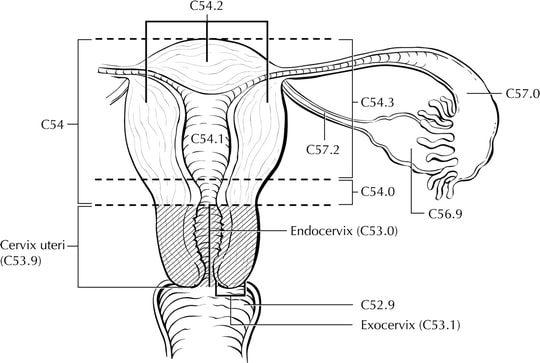

The cervix is the lower third of the uterus. It is roughly cylindrical and projects into the upper vagina (Figure Cervix Uteri-anatomy). The endocervical canal is lined by glandular or columnar epithelium and runs through the cervix; it is the passageway connecting the vagina with the uterine cavity. The vaginal portion of the cervix, known as the exocervix, is covered by squamous epithelium. The original squamocolumnar junction is located on the ectocervix, vaginal fornix, or upper vagina, but squamous metaplasia causes a new squamocolumnar junction to be established at the external cervical os, where the endocervical canal begins. The area between these 2 junctions is called the transformation zone. Cancer of the cervix may originate from the squamous epithelium of the exocervix or the glandular epithelium of the canal; however, most of these cancers arise in the transformation zone.

The anatomy of the cervix is described in Note S: Identification of Primary Site(s) with a figure of the anatomy. The following figures depict the local extent of tumor described in the T categories.

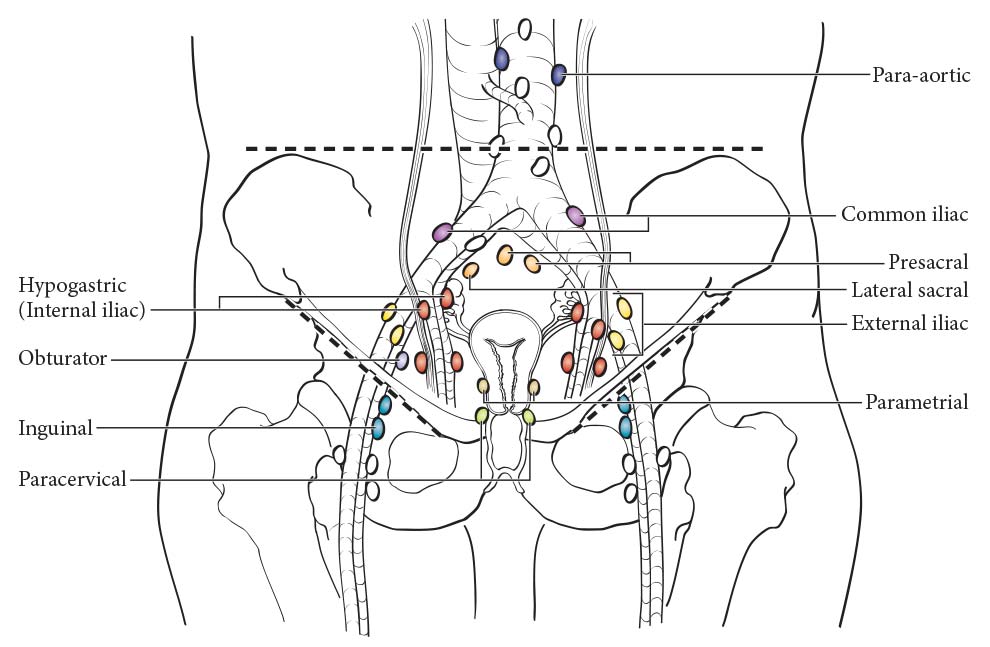

Regional Lymph Nodes

The cervix is drained by parametrial, cardinal, and uterosacral ligament routes into the following regional lymph nodes (Figure 64.1):

- Parametrial

- Obturator

- Internal iliac (hypogastric)

- External iliac

- Sacral

- Presacral

- Common iliac

- Para-aortic

Emerging Factors for Collection

None recommended

Additional Factors Relevant for Clinical

Additional data elements that are clinically significant but not required for staging are identified with a dagger symbol.(†)

- †FIGO stage

- †Tumor Size

- †Lymph Node Metastasis

- †Fractional Depth of Invasion

- †p16 status

- †Histopathologic Type

- †HIV status

- FIGO stage

- p16 status

- Pelvic nodal status and method of assessment (microscopic, CT, PET, MR imaging)

- Para-aortic nodal status and method of assessment

- Distant (mediastinal, scalene) nodal status and method of assessment

- HIV status