Objectives ⬇

- Explore the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996.

- Describe the purposes of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009.

- Appreciate how the HITECH Act enhanced the security and privacy protections of HIPAA and how these protections continue to evolve as health information technology develops.

- Survey the provisions of the 21st Century Cures Act and its impact on health.

Key Terms ⬆ ⬇

Introduction ⬆ ⬇

Two key pieces of legislation were instrumental in shaping the health information technology and nursing informatics (NI) landscape: the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 and the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009. Other legislation, policies, and regulations continue to further the vision initiated by these seminal laws. This chapter presents an overview of the HITECH Act, including the Medicare and Medicaid health information technology (health IT) provisions of the law. Nurses need to be familiar with the goals and purposes of this law and how it enhances the security and privacy protections of HIPAA and appreciate how it otherwise affects nursing practice in the ever-evolving electronic health records age. Key concepts related to legislating health IT are explored in this chapter as well as newer legislation regulating medical devices and apps that support patient centeredness and the movement toward payment based on quality. Figure 8-1 provides a snapshot of the legislation affecting the informatics landscape.

Figure 8-1 Health Informatics Regulations

A list of health informatics regulations includes meaningful use 2010, MACRA 2015, Cures Act 2016, HIPAA 1996, and HITECH 2009.

HIPAA Came First ⬆ ⬇

HIPAA was signed into law by President Bill Clinton in 1996. Hellerstein (1999) summarized the intent of the act as follows: to curtail healthcare fraud and abuse, enforce standards for health information, guarantee the security and privacy of health information, and ensure health insurance portability for employed persons. Consequences were put into place for institutions and individuals who violate the requirements of this act. For this text, we concentrate on the health information security and privacy aspects of HIPAA, which are outlined as follows:

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) Rules contain privacy, security, and breach notification requirements that apply to individually identifiable health information created, received, maintained, or transmitted by health care providers who engage in certain electronic transactions, health transactions, health plans, health care clearinghouses, and their business associates. The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) is the Departmental component responsible for implementing and enforcing the privacy regulation. (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2022, para. 6-7)

The need and means to guarantee the security and privacy of health information were the focus of numerous debates. Comprehensive standards for the implementation of this portion of the act eventually were finalized, but the process to adopt final standards took years. In August 1998, HHS released a set of proposed rules addressing health information management. Proposed rules specific to health information privacy and security were released in November 1999. The purpose of the proposed rules was to balance patients' rights to privacy and providers' needs for access to information (Hellerstein, 2000).

Hellerstein (2000) summarized the proposed privacy rules as follows:

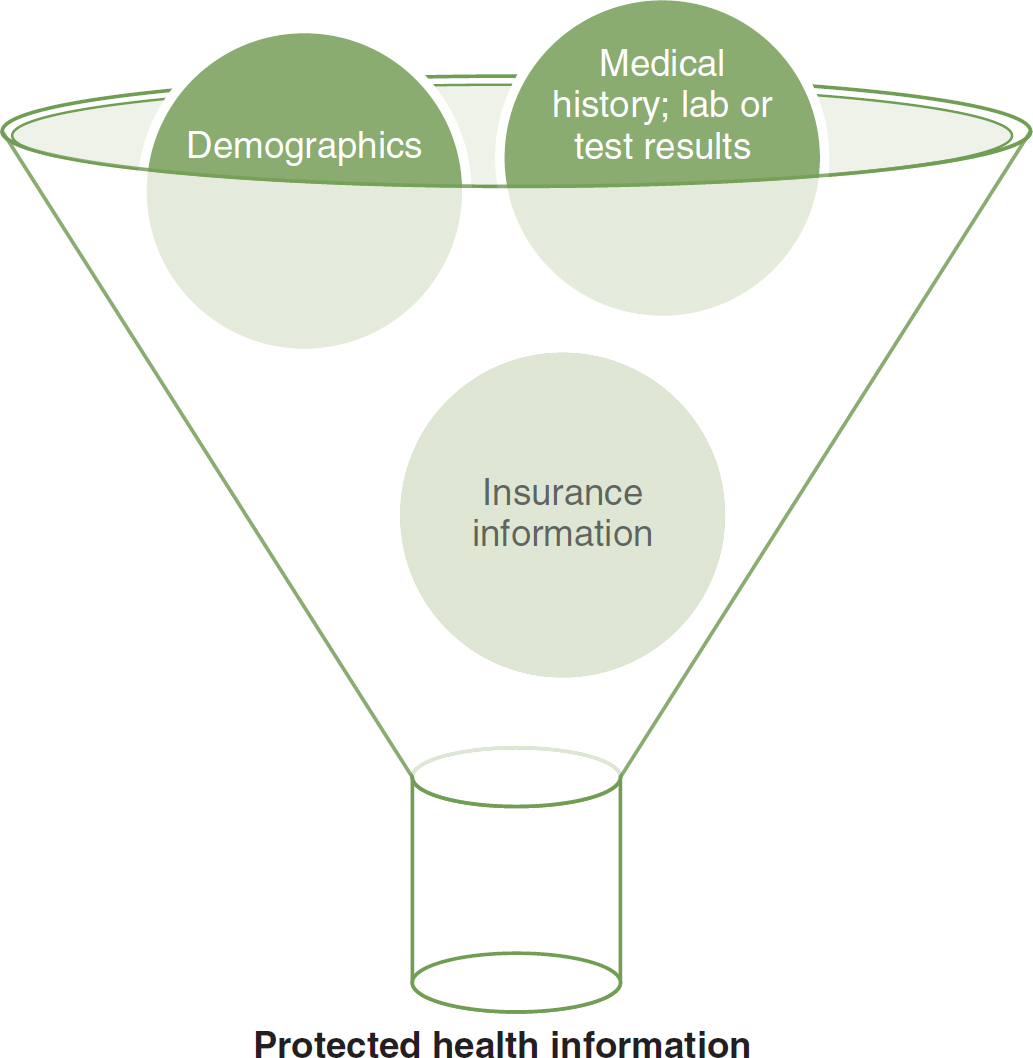

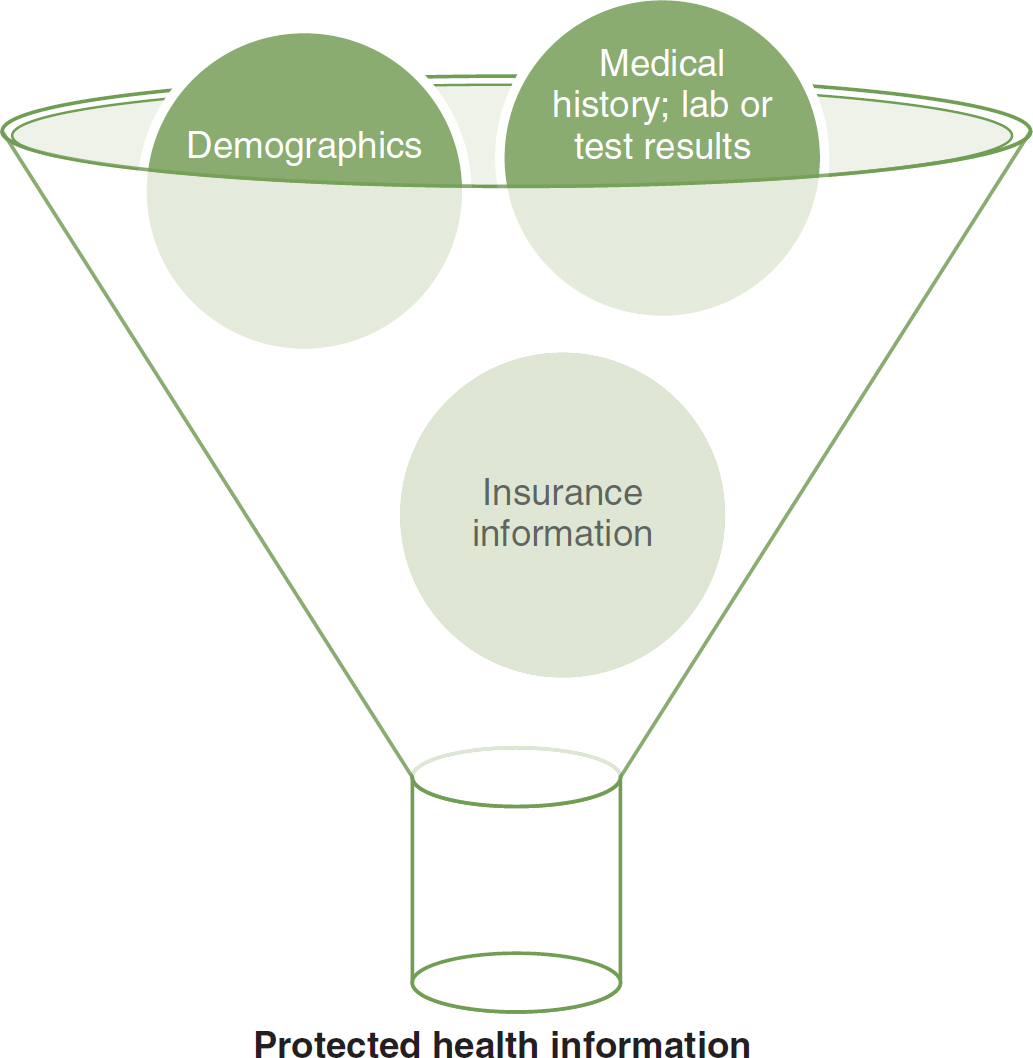

- Define protected health information (PHI) as “information relating to one's physical or mental health, the provision of one's health care, or the payment for that health care, that has been maintained or transmitted electronically and that can be reasonably identified with the individual it applies to” (p. 2). Figure 8-2 depicts the types of information protected under HIPAA.

Figure 8-2 What Is Protected Health Information?

An illustration of a funnel depicts the elements of protected health information, encompassing demographics, medical history, lab or test results, and insurance information.

- Propose that authorization by patients for release of information is not necessary when the release of information is directly related to treatment and payment for treatment. Specific patient authorization is not required for research, medical or police emergencies, legal proceedings, and collection of data for public health concerns. All other releases of health information require a form for each release that specifies which information pertinent to the issue at hand is to be released. All releases of information must be formally documented and accessible to the patient on request.

- Establish patient ownership of the healthcare record and allow for patient-initiated corrections and amendments.

- Mandate administrative requirements for the protection of healthcare information. All healthcare organizations are required to have a privacy official and an office to receive privacy violation complaints. A specific training program for employees that includes a certification of completion and a signed statement by all employees that they will uphold privacy procedures must be developed and implemented. Every 3 years, all employees must re-sign the agreement to uphold privacy. Sanctions for violations of policy must be clearly defined and applied.

- Mandate that all outside entities that conduct business with healthcare organizations (e.g., attorneys, consultants, and auditors) must meet the same standards as those of the organization for information protection and security.

- Allow PHI to be released without authorization for research studies. Patients may not access their information in blinded research studies because their access may affect the reliability of the study outcomes.

- Propose that PHI may be de-identified before release in such a manner that the identity of the patient is protected. The healthcare organization may code the de-identification so that the information can be re-identified once it has been returned.

- Applies only to health information maintained or transmitted by electronic means.

As concerns mounted and deadlines loomed, the healthcare arena prepared to comply with the requirements of the law. The administrative simplification portion of this law was intended to decrease the financial and administrative burdens by standardizing the electronic transmission of certain administrative and financial transactions. This section also addressed the security and privacy of healthcare data and information for the covered entities of healthcare providers that transmit any health information in electronic form in connection with a covered transaction, health plans, and healthcare clearinghouses (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], n.d.-a).

The privacy requirements, which went into effect on April 14, 2003, limited the release of PHI without the patient's knowledge and consent. Covered entities must comply with the requirements. Notably, they must dedicate a privacy officer, adopt and implement privacy procedures, educate their personnel, and secure their electronic patient records. Most individuals are familiar with the need to notify patients of their privacy rights because of their having had to sign forms before interacting with their own healthcare providers.

The Privacy Rule provided certain rights to patients: the right to request restrictions to access of the health record, the right to request an alternative method of communication with a provider, the right to receive a paper copy of the notice of privacy practices, the right to file a complaint if the patient believes their privacy rights were violated, the right to inspect and copy one's health record, the right to request an amendment to the health record, and the right to see an account of disclosures of one's health record. These rights placed the burden of maintaining privacy and accuracy on the healthcare system rather than on the patient.

On October 16, 2003, the standards for electronic transactions and code sets became effective. At that time, the standards did not require electronic transmission but rather mandated that if transactions were conducted electronically, they must comply with the required federal standards for electronically filed healthcare claims. “The Secretary has made the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) responsible for enforcing the electronic transactions and code sets provisions of the law” (Indian Health Service, 2003, para. 3).

The security requirements went into effect on April 21, 2005, and required the covered entities to put safeguards into place that protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of PHI when stored and transmitted electronically.

The safeguards that were addressed were administrative, physical, and technical. The administrative safeguards refer to the documented formal policies and procedures that are used to manage and execute the security measures. They govern the protection of healthcare data and information and the conduct of the personnel. The physical safeguards refer to the policies and procedures that must be in place to limit physical access to electronic information systems. Technical safeguards are the policies and procedures used to control access to healthcare data and information. Safeguards need to be in place to control access, whether the data and information are at rest; residing on a machine or storage medium; being processed; or in transmission, such as being backed up to storage or disseminated across a network.

Overview of the HITECH Act ⬆ ⬇

The federal HITECH Act, enacted February 17, 2009, is part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). The ARRA, also known as the Stimulus law, was enacted to stimulate various sectors of the U.S. economy during the most severe recession this country had experienced since the Great Depression of the late 1920s and early 1930s. The health IT industry was one area where lawmakers saw an opportunity to stimulate the economy and improve the delivery of health care at the same time. This explains why the title of the HITECH Act contains the phrase “for Economic and Clinical Health.”

The ARRA is a lengthy piece of legislation that is organized into two divisions, A and B. Each division contains several titles. Title XIII of Division A of the ARRA is the HITECH Act. It addresses the development, adoption, and implementation of health IT policies and standards and provides enhanced privacy and security protections for patient information-an area of the law that is of paramount concern in NI. Title IV of Division B of the ARRA is considered part of the HITECH Act. It addressed Medicare and Medicaid health IT and provided significant financial incentives to healthcare professionals and hospitals that adopted and engaged in the “meaningful use” of electronic health record (EHR) technology.

At the time the HITECH Act was enacted, it was estimated that fewer than 8% of U.S. hospitals used a basic EHR system in at least one of their clinical units and that fewer than 2% of U.S. hospitals had an EHR system in all of their clinical settings (Ashish et al., 2009). Not surprisingly, the cost of an EHR system was a major barrier to widespread adoption of this technology in most healthcare facilities. The HITECH Act sought to change that situation by providing each person in the United States with an EHR. In addition, a nationwide health IT infrastructure would be developed so that access to a person's EHR would be readily available to every healthcare provider who treats the patient, no matter where the patient may be located at the time treatment is rendered. According to the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), 96% of hospitals and 78% of physician's offices have EHR technology certified by HHS (ONC, n.d.-c).

Definitions

The HITECH Act included some important definitions that anyone involved in NI should know:

- Certified EHR technology: The term certified EHR technology means that an EHR meets specific governmental standards for the type of record involved, whether it be an ambulatory EHR used by office-based healthcare practitioners or an inpatient EHR used by hospitals. The specific standards that are to be met for any such EHRs are set forth in federal regulations.

- Enterprise integration: The term enterprise integration means the electronic linkage of healthcare providers, health plans, the government, and other interested parties to enable the electronic exchange and use of health information among all the components in the healthcare infrastructure.

- Healthcare provider: The term healthcare provider includes hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, nursing homes, long-term care facilities, home health agencies, hemodialysis centers, clinics, community mental health centers, ambulatory surgery centers, group practices, pharmacies and pharmacists, laboratories, physicians, and therapists.

- Health information technology: The term health information technology means “hardware, software, integrated technologies or related licenses, intellectual property, upgrades, or packaged solutions sold as services that are designed for or support the use by healthcare entities or patients for the electronic creation, maintenance, access, or exchange of health information.”

- Qualified electronic health record: The term qualified electronic health record means “an electronic record of health-related information on an individual.” A “qualified” EHR contains a patient's demographic and clinical health information, including the medical history and a list of health problems, and is capable of providing support for clinical decisions and entry of physician orders. It must also have the capacity “to capture and query information relevant to health care quality” and “exchange electronic health information with, and integrate such information from other sources.” (ONC, 2009, pp. 8-9)

Purposes

The HITECH Act established the ONC within HHS. The ONC, headed by the national coordinator, was charged with overseeing the development of a nationwide health IT infrastructure that supported the use and exchange of information to achieve the following goals:

- Improve healthcare quality by enhancing coordination of services between and among the various healthcare providers a patient may have, fostering more appropriate healthcare decisions at the time and place of delivery of services, and preventing medical errors and advancing the delivery of patient-centered care

- Reduce the cost of health care by addressing inefficiencies, such as duplication of services within the healthcare delivery system, and reducing the number of medical errors

- Improve people's health by promoting prevention, early detection, and management of chronic diseases

- Protect public health by fostering early detection and rapid response to infectious diseases, bioterrorism, and other situations that could have a widespread impact on the health status of many individuals

- Facilitate clinical research

- Reduce health disparities

- Better secure patient health information

The responsibilities of the ONC have evolved over time, although the core responsibilities of supporting the adoption of health IT and promoting health information exchange remain unchanged. The ONC's current strategic goals follow:

- Advance person-centered and self-managed health

- Transform health care delivery and community health

- Foster research, scientific knowledge, and innovation

- Enhance the nation's health IT infrastructure (ONC, n.d.-a)

Improving healthcare quality has been an ongoing challenge in the United States. According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), quality health care is “described in terms of six priorities: patient safety, person-centered care, care coordination, effective treatment, healthy living, and care affordability” (AHRQ, 2022, para 1). AHRQ, an agency within HHS, has been releasing a National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report every year since 2003. Access the 2022 report at www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr22/index.html.

The prevalence of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) serves as an excellent example of how the use of EHR technology and a nationwide health IT infrastructure played a significant role in addressing healthcare quality issues. The National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report suggested that “[w]ound infection following surgery is a common HAI. Hospitals can reduce the risk of surgical site infection by making sure patients get the right antibiotics at the right time on the day of their surgery. Surgery patients who get antibiotics within the hour before their operation are less likely to get wound infections than those who do not” (AHRQ, 2009, p. 110). Crader and Varacallo (2020) verified that this is an ongoing and accepted practice. The evolving U.S. health IT infrastructure has enabled us to track this issue for all surgical patients and thus develop evidence-based care plans to ensure that all patients within the infrastructure receive the same quality of care. This is just one of many examples in which the end result of EHR adoption is better patient outcomes.

EHR technology makes it easier for all providers involved in a patient's care to readily access that patient's complete and current healthcare record, thereby allowing providers to make well-informed, efficient, and effective decisions about a patient's care at the time those decisions need to be made. Being able to do this is of tremendous benefit to the patient and promotes a higher level of patient-centered care. It also allows effective coordination of care between and among all providers involved in the patient's care, including doctors, nurses, therapists, nutritionists, hospitals, nursing homes, rehabilitation facilities, home health agencies, laboratories, and other diagnostic centers, thereby assuring the continuum of patient care.

Such an integrated system has clear benefits for patients and providers alike. For example, imagine how much easier it would be for a patient with a rare form of cancer to obtain a second oncologist's opinion before beginning a course of treatment. The patient's complete record, including the results of numerous diagnostic tests conducted at multiple sites, such as blood tests, biopsies, radiographs, and scans, would be readily available to the second oncologist. Imagine how much easier it would be for a patient with end-stage renal disease, who is receiving outpatient hemodialysis several times a week, to receive appropriate treatment if they were suddenly hospitalized or would like to take a vacation out of state. Imagine how much easier it would be for nurses to complete a medication reconciliation for a newly admitted patient. The possibilities are endless, and the savings realized from enhancing quality, avoiding duplication of services, and streamlining delivery of patient care are obvious.

Reducing healthcare errors is another ongoing challenge in the United States. Healthcare providers strive to meet the standard of care and avoid harm to patients. Patients have a right to receive appropriate care, but that does not always happen. The seminal report, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, issued by the Institute of Medicine's Committee on the Quality of Health Care in America, undertook a comprehensive literature review and summarized the results of more than 40 studies about healthcare errors (Institute of Medicine, 2000). That report concluded that approximately 44,000 to 98,000 people in the United States die each year as a result of healthcare errors. Many thousands more who do not die are seriously injured from such errors. In addition to the human pain and suffering associated with healthcare errors, the monetary costs of these errors are substantial. Although progress in reducing healthcare errors has been made since the release of To Err Is Human, substantial work remains to be done. It is anticipated that a nationwide health IT infrastructure will contribute to a reduction in healthcare errors by providing mechanisms to assist with the prevention of errors and to provide timely warnings of the possibility of a repetitive error that may affect many patients.

Containing and reducing healthcare costs in the United States, where more than $4.3 trillion is spent on health care each year with a projected increase by 2028 of $6.2 trillion, is another daunting challenge (CMS, n.d.-c). Using EHR technology and a nationwide health IT infrastructure to improve quality and reduce errors within the healthcare delivery system is one way to address this challenge.

Promoting prevention, early detection, and management of chronic diseases was another purpose of the HITECH Act. The delivery of health care in the United States traditionally has been based on a disease model rather than on a wellness model. Having an EHR for everyone helps with the necessary transition as providers and their patients become more aware of the variables that positively or negatively affect health. The ability to collect and analyze data to identify appropriate choices to promote wellness and either prevent illness and injury or detect and manage chronic diseases sooner is well supported by the EHR.

Chronic diseases are of major concern to this country not only because of the impact they have on individuals but also because of the tremendous cost associated with providing treatment for patients with these conditions. Adult-onset diabetes, for example, has reached epidemic proportions. A national health IT infrastructure helps providers better identify those patients who are at risk for developing this disease and provide treatment strategies to avoid it. Providers of those patients who develop type 2 diabetes can predict and diagnose the condition much sooner and manage it more effectively because of the vast resources provided by the national health IT infrastructure.

Improving public health was another purpose of the HITECH Act. The recent pandemic challenge is illustrative of how a national health IT infrastructure can protect public health by fostering early detection and rapid response to infectious diseases, bioterrorism, and other situations that could have a widespread effect on the health status of many individuals and groups.

The effect that a national health IT infrastructure has and will continue to have on clinical research is self-evident. As the infrastructure evolves, the amount of data that is readily available for clinical research will increase exponentially. The ability of researchers to conduct studies and provide clinicians with the most current evidence-based practice is of tremendous benefit to patients everywhere.

Reducing health disparities was another purpose of the HITECH Act. Disparities are differences in access to and quality of care in subpopulations. Detailed information about healthcare disparities can be found at the website for the Office of Health Equity at www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth. The AHRQ routinely examines the issue of disparities in health care and reports its findings to the public. Access the report at www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/index.html.

All patients, regardless of race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status, should receive care that is effective, safe, equitable, and timely. When the national health IT infrastructure contemplated by the HITECH Act is fully implemented, such disparities are bound to decrease. The ability to monitor for disparities and promote the delivery of appropriate care to all patients will be enhanced. Clinicians will be prompted to base their treatments on appropriate factors and avoid biased care.

Perhaps the most important task that faced the national coordinator during the development and implementation of a nationwide health IT infrastructure was ensuring the security of the PHI within that system. The ability to secure and protect confidential patient information has always been of paramount importance to clinicians, who view this consideration as an ethical and legal obligation of practice. Patients value their privacy, and they have a right to expect that their confidential health information will be properly safeguarded. Nurses have been complying with the regulatory requirements of HIPAA for years, and the HITECH Act enhanced the security and privacy protections each patient has a right to expect under HIPAA. The specific changes are discussed in greater detail later in this chapter.

How a National Health IT Infrastructure Was Developed ⬆ ⬇

Developing a national health IT infrastructure is an enormous and extremely complex undertaking that requires extensive financial, technological, and human resources. The HITECH Act established the ONC, as noted earlier, and HHS appointed a national coordinator who is responsible for the development of the infrastructure. The HITECH Act also established two committees within the ONC: the Health IT Policy Committee and the Health IT Standards Committee.

The Policy Committee was responsible for making recommendations to the coordinator about how to implement the requirements of the HITECH Act, such as the technologies to use in the infrastructure. The Standards Committee was responsible for recommending standards by which health information was to be electronically exchanged. These two committees have since been replaced by the Health Information Technology Advisory Committee (HITAC), established by the 21st Century Cures Act (discussed later). HITAC is charged with recommending “policies, standards, implementation specifications, and certification criteria, relating to the implementation of a health information technology infrastructure, nationally and locally, that advances the electronic access, exchange, and use of health information” (ONC, n.d.-b, para. 1).

The national coordinator is charged with providing overall leadership and strategic direction for the ONC, and these duties will continue to evolve as the health IT infrastructure evolves. The Federal Register has indicated that the national coordinator of the ONC

- ensures the interoperability of health information, as central and foundational to the core mission of HHS to enhance and protect the health and well-being of all Americans;

- ensures that health information technology initiatives are coordinated across HHS programs;

- ensures that health information technology policy and programs of HHS are coordinated with those of relevant executive branch agencies (including Federal commissions and advisory committees) with a goal of avoiding duplication of effort and of helping to ensure that each agency undertakes activities primarily within the areas of its greatest expertise and technical capability;

- reviews Federal health information technology investments to ensure Federal health information programs are meeting the objectives of the strategic plan required under Executive Order 13335, to create a national interoperable health information technology infrastructure;

- provides comments and advice regarding specific Federal health information technology programs; and

- develops, maintains, and reports on measurable outcome goals for health information technology to assess progress within HHS and other executive branch agencies (HHS, 2018)

The HITECH Act also provided significant monetary incentives for providers who engaged in meaningful use of health IT. Meaningful use was defined as “electronically capturing health information in a coded format, using that information to track key clinical conditions, communicating that information to help coordinate care, and initiating the reporting of clinical quality measures and public health information” (CMS, 2010, para. 6). Monetary incentives were available to clinicians and facilities that implemented EHR systems that met the specific standards. The term meaningful use has since been replaced by provisions outlined in the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 2015.

How the HITECH Act Changed HIPAA ⬆ ⬇

HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules

Nurses have been complying with HIPAA for years. HIPAA was enacted by the federal government for several purposes, including better portability of health insurance as a worker moved from one job to another; deterrence of fraud, abuse, and waste within the healthcare delivery system; and simplification of the administrative functions associated with the delivery of health care, such as reimbursement claims sent to Medicare and Medicaid. Simplification of administrative functions entailed the adoption of electronic transactions that included sensitive healthcare information. To protect the privacy and security of health information, two sets of federal regulations were implemented: The Privacy Rule became effective in 2003, and the Security Rule became effective in 2005. Many practitioners who refer to HIPAA are not referring to the comprehensive federal statute enacted in 1996 but rather to the Privacy Rule and the Security Rule, the federal regulations that were adopted years after HIPAA became law.

Under the Privacy Rule, patients have a right to expect privacy protections that limit the use and disclosure of their health information. Under the Security Rule, providers are obligated to safeguard their patients' health information from improper use or disclosure and to maintain the integrity of the information and ensure its availability. Both rules apply to PHI, defined as any physical or mental health information created, received, or stored by a covered entity that can be used to identify an individual patient, regardless of the form of the health information (i.e., it can be electronic, handwritten, or verbal) (Legal Information Institute, 2013). Covered entities include hospitals and other healthcare providers that transmit any health information electronically as well as health insurance companies and healthcare clearinghouses (Legal Information Institute, 2013).

Clinicians have become very knowledgeable about the requirements of the Privacy and Security Rules. They are familiar with their obligations to protect patient information and the rights afforded to their patients under these regulations:

- Patients are entitled to a notice of privacy practices from their healthcare provider.

- Inpatients are entitled to opt out of the facility's directory, thereby protecting disclosure of information that they are even a patient in the facility.

- Under certain circumstances, patients must authorize disclosure of their PHI before it can be released by the provider.

- Patients can request and obtain access to their own healthcare records and may request that corrections and additions be made to their records. Providers must consider a patient's request to amend a healthcare record, but they are not required to make such an amendment if the request is unwarranted.

- Unauthorized access or use or any loss of healthcare information must be disclosed to any patient affected by the breach.

- Patients may request an accounting of anyone who accessed their healthcare information, and the provider is required to provide that information in a timely manner.

- Patients have a right to complain if they perceive that the privacy or security of their healthcare information has been compromised in some way. Such complaints can be made directly to the provider or to the Office for Civil Rights (OCR).

The OCR, which is part of HHS, is responsible for enforcing HIPAA. It provides significant information and guidance to clinicians who must comply with the Privacy and Security Rules. It has been tracking complaints and investigating violations since 2003. Guidance and information about the complaint process and the violations that the OCR has handled are available on its website at www.hhs.gov/hipaa/filing-a-complaint/index.html. As an example, snooping of healthcare records of friends and neighbors is a common HIPAA violation. Even if the information is not disclosed to anyone else, it is still a violation to access records of persons whom one is not assigned to care for. Disciplinary actions may include termination (HIPAA Journal, 2023a).

Many businesses are moving to enact a “bring your own device” (BYOD) policy for employees. This policy, which helps to streamline the lives of employees by maintaining personal and business information on one device, can also result in cost savings for the organization overall. BYOD is an issue, however, when dealing with PHI. Healthcare organizations typically do not encourage the use of personal devices for professional matters, and in many instances, they have policies in place forbidding employees from using personal devices in the workplace. According to Pennic (2013), approximately 50% of healthcare organizations reported that personal mobile devices can be used to access the internet within their facilities but these devices were not given access to the organization's network. For a long time, only devices that were issued by the organization, secured, and routinely audited were able to access the secure network; however, workers were not happy carrying more than one device. Kleyman (2018) pointed out that “[i]f we want to keep an effective and productive healthcare workforce, we need to find a balance between connection and control” (para. 7). He suggested several strategies to support workflow and provide appropriate security:

- Detail and document your users, their mobile interactions, and their use-case

- Design a mobility and BYOD workflow that works and is secure

- Leverage EMM/MDM [enterprise mobility management/mobile device management] and mobility control technologies to improve user experience while still locking things down

- Enable network-level visibility, DLP [data loss prevention], and data scanning (para. 22-25)

As more healthcare workers used personal devices in the workplace, policies began to change to ensure HIPAA compliance. Wani et al. (2020) suggested several technologies to address BYOD security risks. These include a mobile device management platform to provide central management of devices, including registration/deregistration, encryption, log off, device tracking and data wiping; containerization to separate personal and organization data; virtual desktop infrastructure that eliminates organizational data storage on personal devices; identity and access management; and secure clinical communication platforms. See this website for a list of ways to handle personal devices and maintain the security of PHI: www.healthit.gov/topic/privacy-security-and-hipaa/how-can-you-protect-and-secure-health-information-when-using-mobile-device.

Compliance with the Privacy and Security Rules is mandatory for all covered entities, and the HITECH Act extends compliance with these requirements directly to other entities that are business associates of a covered entity. Requirements include designation of privacy and information security officials to protect health information and appropriate handling of any complaints. Sanctions must be imposed if a violation of HIPAA occurs. The Privacy and Security Rules also mandated that certain physical and technical safeguards be implemented for PHI and that entities conduct periodic training of all staff to ensure compliance with these safeguards. Most entities adhere to industry standards and provide their personnel with yearly training. In addition, entities are to conduct regular audits to ensure compliance, and any breaches in the privacy or security of PHI must be remedied immediately. It is important to avoid a security incident because such incidents trigger certain notification requirements and may be associated with monetary penalties.

The HITECH Act Enhanced HIPAA Protections

The HITECH Act has had a significant effect on HIPAA's Privacy and Security Rules in the following ways:

- HHS is to provide annual guidance about how to secure health information.

- Notification requirements in the event of a breach in the security of health information were enhanced.

- HIPAA requirements now also apply directly to any business associates of a covered entity.

- The rules that pertain to providing an accounting to patients who want to know who accessed their health information were changed.

- Enforcement of HIPAA was strengthened.

These measures were implemented to provide further assurance that health information would be protected as the country transitioned to a nationwide health IT infrastructure. Privacy and data regulations are also being established around the world. See a map of the world depicting the laws of various countries at this website: https://iapp.org/resources/article/dla-piper-data-protection-laws-of-the-world. It is quite evident that privacy and security are global concerns.

Several standards-setting organizations are also involved in the privacy and security aspects of the health IT infrastructure development (Box 8-1).

| Box 8-1 Standards-Setting Organizations |

|---|

| The following organizations are recognized by the Secretary of Health of HHS as standards-setting organizations and groups that support the administrative simplification aspects of HIPAA. Each organization is followed by a link to its web page. This information is used with permission from www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Administrative-Simplification/HIPAA-ACA/StandardsSettingandRelatedOrganizations. |

| Advisory Groups |

|---|

- National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (NCVHS)

- Workgroup for Electronic Data Interchange (WEDI)

|

| Designated Authoring Entity for Operating Rules |

|---|

- Committee on Operating Rules for Information Exchange (CAQH CORE)

|

| Designated Standard Maintenance Organizations (DSMOs) |

|---|

- Dental Content Committee of the American Dental Association (ADA DeCC)

- Accredited Standards Committee (ASC X12)

- Health Level Seven (HL7)

- National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP)

- National Uniform Billing Committee (NUBC)

- National Uniform Claim Committee (NUCC)

|

| Non-Designated Standard Maintenance Organizations |

|---|

- American National Standards Institute (ANSI)

- Electronic Healthcare Network Accreditation Commission (EHNAC)

- Health Industry Business Communications Council (HIBCC)

- Electronic Payments Association (Nacha)

- National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC)

- National Information Standards Organization (NISO)

|

Avoiding security incidents has become a paramount concern for healthcare organizations and providers. Providers must protect their information and prevent unauthorized persons from accessing, using, disclosing, changing, or destroying a patient's health information or otherwise interfering with the operations of a health information system, such as an EHR. PHI can be secured through encryption, shredding and other forms of complete destruction, or electronic media sanitation. For an overview of two methods for de-identifying PHI, visit www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/special-topics/de-identification/index.html.

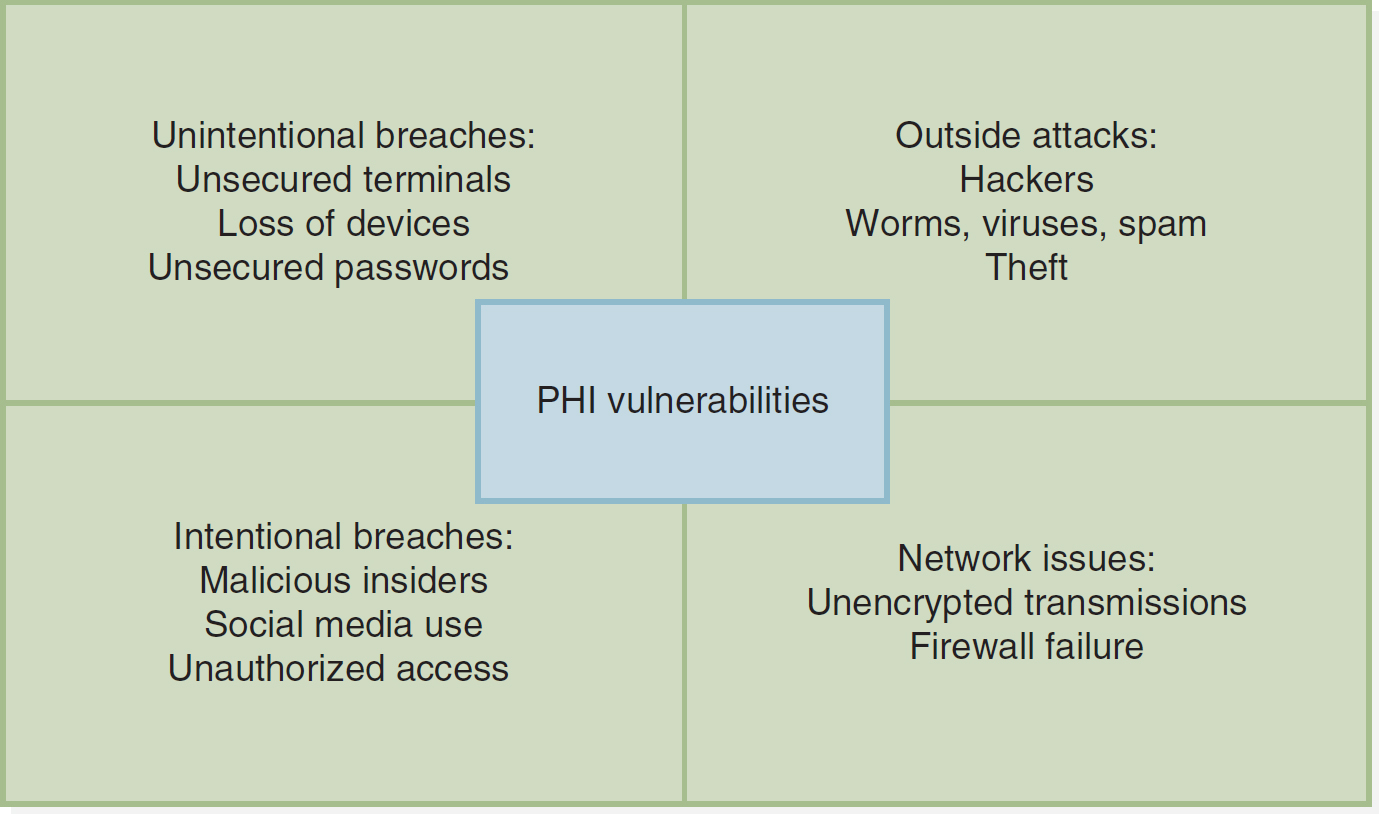

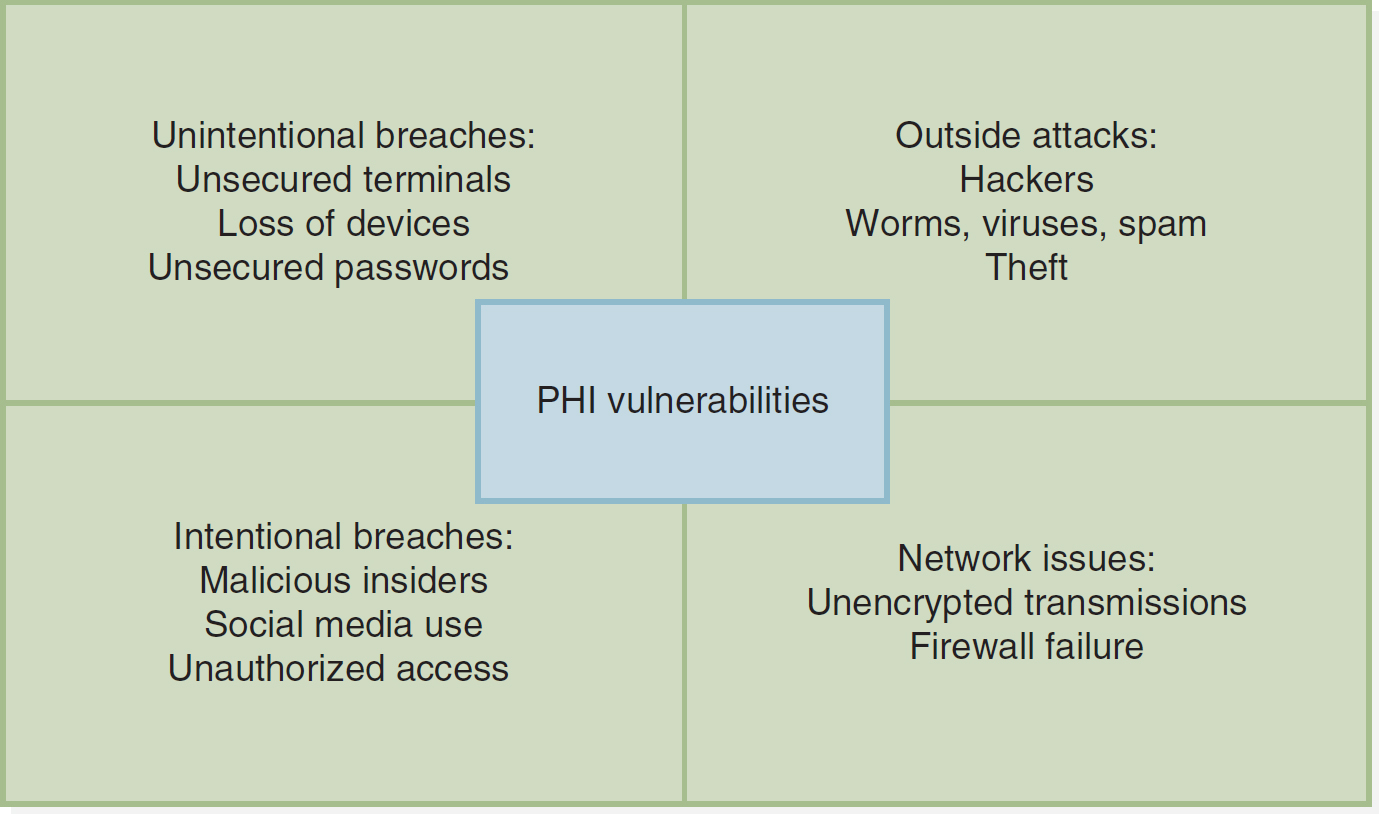

Figure 8-3 depicts some common causes of PHI vulnerabilities.

Figure 8-3 Vulnerability of Private Health Information

A box divided into four equal sections depicts the vulnerability of private health information.

The P H I vulnerabilities are as follows. Unintentional breaches: Unsecured terminals; Loss of devices; Unsecured passwords. Outside attacks: Hackers; Worms, viruses, spam; Theft. Intentional breaches: Malicious insiders; Social media use; Unauthorized access. Network issues: Unencrypted transmissions; Firewall failure.

The distinction between secured and unsecured PHI is important because providers that experience a breach in the privacy or security of their PHI must adhere to certain notification requirements depending on the type of PHI affected by the breach. The HITECH Act enhanced the breach notification requirements of HIPAA. If the PHI is unsecured, the provider must take certain steps to notify those individuals who have been affected. Providers can avoid these onerous breach notification requirements if the PHI is secured in accordance with the specifications of HHS.

A breach is considered discovered as soon as an employee other than the individual who committed the breach knows or should have known of the breach, such as unauthorized access or even an unsuccessful attempt to access information. For example, if a nurse knows that a colleague has accessed or attempted to access the record of a patient for whom the colleague is not providing care, the nurse's employer is deemed to have discovered the breach as soon as the nurse learned of it. The discovery of a breach triggers the beginning of the time frame during which the provider must fulfill the notification requirements. A provider must fulfill these requirements within a reasonable period; under no circumstances may a provider take more than 60 days from discovery of the breach. It is easy to understand why providers require their employees to report knowledge of such breaches immediately to the privacy or information security officer. A provider's failure to adhere to the breach notification requirements could result in OCR sanctions, including monetary penalties.

Whenever a breach involves unsecured PHI, covered entities are responsible for alerting each affected individual by mail or email, based on the individual's preference. If there is insufficient contact information for 10 or more patients, the provider is required to place conspicuous postings on the home page of its website or in major print or broadcast media (without identifying patients). A toll-free number must be provided so that affected individuals can call for information about the breach. For breaches involving unsecured PHI of more than 500 individuals, a prominent media outlet must also be notified. Notice of a breach must be given to HHS within 60 calendar days of the discovery (HHS, 2015). It is easy to see why providers would want to avoid these requirements by making sure that their PHI is secured. Having to post such notices undermines the trust that exists between healthcare providers and the patients and communities they serve.

The HITECH Act has improved the privacy and security of PHI by applying the requirements of HIPAA directly to the business associates of covered entities. In the past, it was up to the covered entity to enter into contracts with its business associates to ensure compliance with HIPAA. Now business associates are responsible for their own compliance. An example of such a business associate is a health IT company hired by a hospital to implement or upgrade an EHR system. The technology company has access to the hospital's EHR system and must comply with the HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules, just as covered entities must comply with these rules, which includes being subject to enforcement by the OCR for any violations.

Existing accounting rules are enhanced under the HITECH Act, giving patients the right to access their EHR and receive an accounting of all disclosures. Before the HITECH Act, HIPAA regulations provided an exception to the accounting requirements. Providers and other covered entities were not required to include in the accounting any disclosures that were made to facilitate treatment/payment/operations (TPO)-treatment of patients, the payment for services, or the operations of the entity-a provision commonly known as the TPO exception. This exception ended in January 2011 for providers that recently implemented new EHR systems. For those providers with EHR systems that were implemented before the HITECH Act, the TPO exception ended in January 2014. It is easy to understand why this exception has ended. As all providers implement comprehensive EHR systems, it will be very easy to generate an electronic record with an accounting of anyone who accessed a patient's record.

Finally, the HITECH Act strengthened the enforcement of HIPAA. HHS can conduct audits, which will be even easier to accomplish once a nationwide health IT infrastructure is in place. In addition, stiffer civil monetary penalties (CMPs) for violations of HIPAA became effective as soon as the HITECH Act became law in February 2009. They were revised in 2019 to reduce the maximum penalty for Tiers 1 through 3. CMPs are divided into four tiers. A Tier 1 CMP, in which the covered entity had no reason to know of a violation, is $100 per incident, up to a cap of $25,000 per year. A Tier 2 CMP, in which the covered entity had reasonable cause to know of a violation, is $1,000 per incident, up to a cap of $100,000 per year. A Tier 3 CMP, in which the covered entity engaged in willful neglect that resulted in a breach, is $10,000 per incident, up to a cap of $250,000 per year. In addition, the HITECH Act gives authority to impose an additional Tier 4 CMP of $50,000 to $1.5 million if the covered entity does not properly correct a violation. Criminal penalties also can be imposed when warranted. It is imperative that providers avoid these penalties (HHS, 2019). The HIPAA Journal (2023b) notes that the OCR has discretion when applying penalties and that the actual dollar amounts change yearly with inflation.

Before enactment of the HITECH Act, the federal government alone enforced HIPAA. Now state attorneys general can play a significant role in the enforcement and prosecution of HIPAA violations. Once the HITECH Act became law, state attorneys general were authorized to pursue civil claims for HIPAA violations and collect up to $25,000 plus attorneys' fees. As of 2012, individuals who are damaged by such violations became eligible to share in any monetary awards obtained by these state officials. For very specific and current HIPAA information, see www.hhs.gov/hipaa/index.html.

Interestingly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Secretary of Health and Human Services issued a limited waiver of HIPAA sanctions and penalties in response to the declaration of a national emergency. Read here the bulletin detailing HIPAA requirements and limited sanctions during a national emergency: www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/hipaa-and-covid-19-limited-hipaa-waiver-bulletin-508.pdf.

Implications for Nursing Practice ⬆ ⬇

Being Involved and Staying Informed

The development and implementation of a nationwide EHR system holds great promise for nursing practice and NI. The profession of nursing will benefit from the many enhancements such an infrastructure has to offer, including the ability to improve the delivery and quality of nursing care, making more efficient and timely nursing care decisions for patients, avoiding errors that may harm patients, and promoting health and wellness for the patients whom nurses serve. On a broader scale, nurse researchers will have the ability to more readily access data that can be used to continue to foster evidence-based practice. For those who devote their professional careers to NI or plan to do so, the opportunities abound. Much work remains to be done as this country transitions to a nationwide health IT infrastructure.

All nurses need to be engaged in this process, whether they treat patients, are managers within healthcare organizations, teach, develop computer programs, or help create institutional or governmental policies. Nurses, as the end users of developing technologies, cannot afford to be left behind in these exciting times. Their voices must be heard, whether within the facility in which they work as changes to the EHR system are contemplated or in the public policy arena. How often are nurses the last to know that a new EHR system has been adopted by their hospital? How many times have nurses been trained to use a system that would have benefited from their input before it was implemented or even purchased? Often, nurses are not invited to the table when entities make decisions about informatics. They should not be afraid to ask to be included, whether to be heard within the workplace or within the governmental agencies that are overseeing the changes that are taking place.

Even nurses who do not get involved in this process need to stay current with the rapid changes that are taking place. Information about federal initiatives is available from the ONC and the OCR. Both offices are housed within HHS and are excellent resources for additional information about the HITECH Act and HIPAA. Regulations to implement the HITECH Act and enhance the HIPAA protections required by it are being proposed and adopted at a rapid pace.

Protecting Yourself

Nurses who strive to protect the privacy and security of patient information are protecting themselves from ethical lapses and violations of law. The American Nurses Association's (ANA's) Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements mandates that nurses protect a patient's rights to privacy and confidentiality.

Associated with the right to privacy, the nurse has a duty to maintain the confidentiality of all patient information. Nurses who engage with social media need to be especially cognizant of the potential for breaching the confidentiality of patient information. Box 8-2 provides more information related to nurses' use of social media. Refer also to the ethical use of social media discussed in Chapter 5, Ethical Applications of Informatics. The patient's well-being could be jeopardized and the fundamental trust between patient and nurse destroyed by unnecessary access to data or the inappropriate disclosure of identifiable patient information. The rights, well-being, and safety of the individual patient should be the primary factors in arriving at any professional judgment concerning the disposition of confidential information received from or about the patient, whether oral, written, or electronic. The standard of nursing practice and the nurse's responsibility to provide quality care require that relevant data be shared with only those members of the healthcare team who have a need to know that information. Only information pertinent to a patient's treatment and welfare should be disclosed and only to those directly involved with the patient's care. When using electronic communications, special effort should be made to maintain data security (ANA, 2015).

| Box 8-2 Use of Social Networks by Nurses |

|---|

| New opportunities to share information via social networks have grabbed the headlines. Since their inception in 2004, the growth in popularity of social networking platforms, such as Facebook (www.facebook.com) and X (formerly Twitter) (www.twitter.com), has been phenomenal. What makes these sites so attractive? Web-based applications, such as Facebook, allow users to connect and share information in ways that were not previously possible. Users develop online profiles that contain information they choose to share with others. Using simple online utilities, users can easily connect and share their profiles and communicate with friends over the internet. Virtual groups of users with similar profiles may be created, connecting users with others who have similar interests. X (Twitter), a microblogging platform, allows users to create interpersonal networks for socializing, support, and information sharing. The power of such tools as X (Twitter) lies in their being lightweight, their limiting of updates to 280 or fewer characters, and their convenience-users can update their status from any device that has an internet connection or text messaging capabilities.

The popularity of social and mobile networking applications is one indication of how new web-based technologies are changing communication preferences. The web is no longer a destination place but instead has become a vehicle of communication where individuals use application software (app), which is installed or downloaded, to connect with others. Individuals act as their own portal and can connect from anywhere with their various communities. This makes it difficult to separate communities and social networks. Where once it was relatively easy to separate work relationships from friends and family, networked communities tend to overlap, which blurs the boundaries between them. The phenomenon of overlapping networks means that the unintended audience is almost always greater than the intended one. A status update that may be construed as harmless and funny to one's friends could be taken in an entirely different way by family or colleagues. This is not to say networked communities are harmful or bad. Indeed, the benefits of such communities far exceed their negatives. However, the immediacy and permanence of the updates shared mean that the user must think about the impact beyond the intended audience in ways never before required (Johnson & Swain, 2011).

Nurses and other healthcare workers who use social media must be aware that the overlapping of networks may unintentionally create privacy and confidentiality breaches. Even when patients are not identified by name, general sharing of information or venting about a difficult day may constitute a privacy breach. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (2011) has collaborated with the ANA in a white paper to develop specific guidelines for the use of social media by nurses. Read the white paper discussing common misconceptions about social media, consequences for breaching confidentiality using social media, guidelines for appropriate use of social media, and case scenarios with discussion.

|

The similarities between these ethical obligations and the legal requirements of HIPAA and other federal and state privacy and confidentiality laws are readily apparent to nurses. By complying with their ethical code, nurses were complying with the Privacy and Security Rules before they were required to do so. Since the adoption of the HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules and the strengthening of the rules by the HITECH Act, it is more important than ever for nurses to understand their obligations in this area and to avoid the pitfalls of violations.

In addition to the sanctions imposed by the OCR, violations can lead to disciplinary actions, as well as litigation, by employers and professional licensing boards. Such actions can have a serious negative effect on the nurse's reputation and financial well-being. If a nurse is terminated for invading a patient's privacy or breaching the confidentiality of a patient's information, some state laws require reporting the information to prospective employers of the nurse; other laws require reporting the information to the state board of nursing. State boards of nursing have the authority to publicly discipline a nurse who has engaged in professional misconduct by invading a patient's privacy, which includes inappropriately accessing a patient's EHR and breaching confidentiality of patient information, such as allowing or tolerating unauthorized access to a patient's EHR. These types of situations can also cause patients to file complaints with the OCR and lawsuits against the offenders. Nurses must be ever mindful of their obligation to report a breach in the privacy or security of PHI to their employers, even if it entails reporting a colleague.

Finally, some view the EHR as a convenient method for employers to monitor the performance of their nurses. Clearly, an EHR system provides a wealth of information that can be, and often is required to be, monitored. Audits are required to make sure that no breaches in the system's security occur. Audits are not necessarily required to determine, for example, which nurses are failing to complete the hospital's documentation requirements in a timely fashion, which nurses are improperly altering (attempting to correct) the record, or which nurses are dispensing more pain medication than the average. Nurses have been challenged by employers who allege failure to document, improper or false documentation, and suspected diversion of narcotics. These types of situations are unsettling and may be on the rise as more providers adopt sophisticated EHR systems. Thus, it behooves every nurse who works with such a system to obtain proper training and to know the policies and procedures that pertain to its use.

Social media can and should be used in an appropriate manner by professionals to educate and promote health behaviors in the clients they serve, communicate with clients if they choose this method of communication, and network with other professionals by sharing information (de-identified) and knowledge. As Gagnon and Sabus (2015) suggested, “the reach of social media for health and wellness presents exciting opportunities for the health care professional with a well-executed social media presence. Social media give health care providers a far-reaching platform on which to contribute high-quality online content and amplify positive and accurate health care information and messages. It also provides a forum for correcting misinformation and addressing misconceptions” (p. 410). They advocated for healthcare professionals to practice digital professionalism and for social media use to be one of the professional competencies for health professional education. Bazan (2015) suggested that social media can be used to consult with other healthcare providers, such as in a professional Facebook group, using direct private messaging between the two providers, but cautioned that posting to the main social site cannot contain any hint of PHI. He also shared information about a progressive medical practice that communicates with patients via private messaging on Facebook. Pershad et al. (2018) suggested that X (Twitter) is a great collaborative and communication tool for patients, physicians, and researchers. They caution, however, that dangerous misinformation can also be shared by nonexperts on this platform. Remember that everything you do electronically leaves a digital footprint. Proceed with caution and be certain that your digital interactions comply completely with professional ethics, laws, and organizational policies.

Recent Laws and Regulations ⬆ ⬇

In 2015, MACRA (HHS, 2016) was released by CMS. Although this legislation primarily affects provider payments based on quality care, all members of the healthcare team will have a hand in helping to ensure quality care. This new legislation replaced the former CMS meaningful use guidelines and rewards clinicians for value over volume. A key component of this legislation was the replacement of Social Security numbers on Medicare cards by April 2019 (CMS, n.d.-b). Updates to this legislation and implementation rules and guidelines can be found at the CMS website at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a division of HHS, is responsible for regulating medical devices to ensure public safety. In 2015, in response to the proliferation of mobile medical applications, the FDA released a guidance document for manufacturers, developers, and FDA staff, which was revised in 2019 and again in 2022. Currently, the most common types of these mobile or smartphone-based apps are not regulated by the FDA because they are not defined as medical devices. An app is defined as a medical device and may be subject to regulation by the FDA if “the intended use of a mobile app is for the diagnosis of a disease or other conditions, or the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease, or if it is intended to affect the structure or function of the body of man” (FDA, 2022, p. 8). The guidance document also provides a list of examples of apps that are not currently viewed as medical devices, such as apps that help users organize personal medical data, track fitness, or self-manage a disease. If, however, the mobile app is an accessory to a regulated medical device, then it is also considered a medical device and is subject to FDA oversight. For those who are interested in developing mobile health apps in the future, the FDA provides an interactive website to help determine whether the device would need to be regulated (www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/mobile-health-apps-interactive-tool). We must be aware that as these mobile apps become more sophisticated in the future, they may indeed be subject to more stringent oversight by the FDA to ensure consumer safety.

The 21st Century Cures Act signed into law in 2016 contains several provisions that are specific to informatics. In general, the Cures Act was designed to provide funding streams and promote research into preventing and curing serious illnesses, ensure medication and medical device development, support community mental health efforts, and improve interoperability and health information exchange by providing seamless access to improved EHRs. Interestingly, there is a provision barring the FDA from regulating mobile health apps that support wellness as long as the app does not diagnose or treat disease. The act also clarifies HIPAA privacy rules when a patient is incapacitated and unable to make decisions (Lengyel-Gomez, 2017). The most interesting part of the Cures Act is the focus on interoperability by requiring a standardized application programming interface (API), creating a Trusted Exchange Network, and forbidding the blocking of health information exchanges. These items are detailed in the Cures Act Final Rule, which puts patients at the center so that IT will do the following:

- Enable patients to make choices that work for them by increasing transparency into the cost and outcomes of care

- Allow patients to shop for and understand their options in getting medical care

- Provide patients with convenient, easy access and visualizations of health information through smartphone apps

- Support an “app economy” that provides innovation and choice to patients, physicians, hospitals, payers, and employers (ONC, n.d.-d, para. 5)

Stay tuned for HIPAA Privacy Rule changes likely to be announced in mid-2023. According to Clark (2023), the stated reasons for the 2023 Privacy Rule changes include

- Strengthening patient rights to access their own PHI,

- Managing information sharing for care coordination and case management,

- Family and caregiver involvement for individuals experiencing emergencies and health crises,

- Providing guidance for disclosures of PHI to facilitate patient care during an emergency situation, and

- Reducing administrative burden (para. 6)

The Kaiser Family Foundation periodically publishes the U.S. Global Health Legislation Tracker, which provides a list of legislation being considered by Congress. Access the tracker at www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/fact-sheet/u-s-global-health-legislation-tracker.

Summary ⬆ ⬇

The HITECH Act and the HIPAA Privacy Rule and Security Rule are intended to enhance the rights of individuals. These laws provide patients with greater access and control over their PHI. They can control its uses, dissemination, and disclosures. Covered entities must establish not only a required level of security for PHI but also sanctions for employees who violate the organization's privacy policies and administrative processes for responding to patient requests regarding their information. Therefore, they must be able to track the PHI, note access from the perspective of which information was accessed and by whom, and identify any disclosures. Finally, readers should recognize that there is global awareness of the need for privacy protections for personal information or PHI.

Over the next few years, international efforts will accelerate to enhance international data exchange. We will come to appreciate the importance of data and terminology standards that support seamless exchange. We may also see additional legislation designed to safeguard PHI while at the same time enhancing and enabling the use of healthcare data to promote health.

| Thought-Provoking Questions |

|---|

- One of the biggest problems with healthcare information security has always been inappropriate use by authorized users. How do HIPAA and the HITECH Act help to curb this problem?

- How do you envision privacy rules, HIPAA, and the HITECH Act evolving in the next decade?

- If you were the privacy officer in your organization, how would you address the following?

- Tracking each point of access of the patient's database, including who entered the data

- Encouraging employees to report privacy and security breaches

- The healthcare professionals are using smartphones, iPads, and other mobile devices. How do you address privacy when data can literally walk out of your setting?

- You observe one of the healthcare professionals using their smartphone to take pictures of a patient. They see you and, in front of the patient, say, “I am not capturing their face!” How do you respond to this situation?

|

References ⬆

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2009). National healthcare quality report.https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqr09/nhqr09.pdf

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2022). 2022 national healthcare quality and disparities report. www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr22/index.html

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. www.nursingworld.org/coe-view-only

- Ashish K. J., DesRoches C. M., Campbell E. G., Donelan K., Rao S. R., Ferris T. G., Shields A., Rosenbaum S., & Blumenthal D. (2009). Use of electronic health records in U.S. hospitals. New England Journal of Medicine, 360(16), 1628-1638. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa0900592

- Bazan J. (2015). HIPAA in the age of social media. Optometry Times, 7(2), 16-18.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (n.d.-a). HIPAA and administrative simplification: Administrative simplification overview. www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Administrative-Simplification/HIPAA-ACA/index

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (n.d.-b). MACRA.www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (n.d.-c). NHE fact sheet.www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nhe-fact-sheet

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2010, July 16). CMS finalizes definition of meaningful use of certified electronic health records (EHR) technology. www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/cms-finalizes-definition-meaningful-use-certified-electronic-health-records-ehr-technology

- Clark D. (2023). Proposed modifications to the HIPAA Privacy Rule 2023: What to know and how to prepare. HIPAAtrek. https://hipaatrek.com/hipaa-privacy-rule-2023-what-to-know-and-how-to-prepare

- Crader M. F., & Varacallo M. (2020). Preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis. StatPearls. www.statpearls.com/kb/viewarticle/27671

- Gagnon K., & Sabus C. (2015). Professionalism in a digital age: Opportunities and considerations for using social media in health care. Physical Therapy, 95(3), 406-414. http://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130227

- Hellerstein D. (1999). HIPAA's impact on healthcare. Health Management Technology, 20(3), 10-12, 14-15. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10351268

- Hellerstein D. (2000). HIPAA and health information privacy rules: Almost there. Health Management Technology, 21(4), 26, 28, 30-31. PMID:11066924

- HIPAA Journal. (2023a, January 2). The ten most common HIPAA violations you should avoid. www.hipaajournal.com/common-hipaa-violations

- HIPAA Journal. (2023b, January 1). What are the penalties for HIPAA violations?www.hipaajournal.com/what-are-the-penalties-for-hipaa-violations-7096

- Indian Health Service. (2003). Guidance on compliance with HIPAA transactions and code sets. www.ihs.gov/sites/hipaa/themes/responsive2017/display_objects/documents/guidance-final.pdf

- Institute of Medicine. (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system. National Academies Press.

- Kleyman B. (2018, January 29). 4 Key ways to overcome healthcare BYOD security challenges. HealthITSecurity. https://healthitsecurity.com/news/4-key-ways-to-overcome-healthcare-byod-security-challenges

- Legal Information Institute. (2013). 45 CFR § 160.103 - Definitions. www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/45/160.103

- Lengyel-Gomez B. (2017, February 20). 21st Century Cures Act-A summary. Healthcare Information Management and Systems Society. www.himss.org/resources/21st-century-cures-act-summary

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. (n.d.-a). About ONC: What we do. www.healthit.gov/topic/about-onc

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. (n.d.-b). Health Information Technology Advisory Committee (HITAC). www.healthit.gov/hitac/committees/health-information-technology-advisory-committee-hitac

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. (n.d.-c). National trends in hospital and physician adoption of electronic health records.www.healthit.gov/data/quickstats/national-trends-hospital-and-physician-adoption-electronic-health-records

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. (n.d.-d). The ONC Cures Act final rule. www.healthit.gov/cures/sites/default/files/cures/2020-03/TheONCCuresActFinalRule.pdf

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. (2009). Index for excerpts from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA). www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/hitech_act_excerpt_from_arra_with_index.pdf

- Pennic J. (2013, June 11). 3 Do's and don'ts of effective HIPAA compliance for BYOD & mHealth. HIT Consultant. https://www.hhs.gov/foia/privacy/index.html

- Pershad Y., Hangge P., Albadawi H., & Oklu R. (2018). Social medicine: Twitter in healthcare. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 7(6), 121-130. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7060121

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2015). Submitting notice of a breach to the secretary.www.hhs.gov/guidance/document/breach-reporting-submitting-notice-breach-secretary

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). Administration takes first step to implement legislation modernizing how Medicare pays physicians for quality. https://wayback.archive-it.org/3926/20170127191630/https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2016/04/27/administration-takes-first-step-implement-legislation-modernizing-how-medicare-pays-physicians.html

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2018). Statement of organization, functions, and delegations of authority; Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-05-02/pdf/2018-09361.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2019). 45 CFR part 160: Notification of enforcement discretion regarding HIPAA civil money penalties. www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-04-30/pdf/2019-08530.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022, August 31). The Privacy Act. www.hhs.gov/foia/privacy/index.html

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2022, September 28). Policy for device software functions and mobile medical applications. www.fda.gov/media/80958/download

- Wani T. A., Mendoza A., & Gray K. (2020). Hospital bring-your-own-device security challenges and solutions: Systematic review of gray literature. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(6), e18175. https://doi.org/10.2196/18175