Objectives ⬇

- Define health literacy and eHealth.

- Explore various technology-based approaches to consumer health education.

- Assess barriers to the use of technology and the issues associated with health-related consumer information.

- Imagine future approaches to technology-supported consumer health information.

Key Terms ⬆ ⬇

Introduction ⬆ ⬇

Imagine that you have decided to take up running as your preferred form of exercise in a quest to get in shape. You start slowly by running a half mile and walking a half mile. You gradually build up your endurance and find yourself running nearly every day for longer distances and longer periods of time. But then you notice a nagging pain in your right hip; over a few weeks, it gradually spreads to the center of your right buttock and then down your right leg. You try rest and heat, but nothing seems to help. You visit your doctor, who indicates that you have developed piriformis syndrome and prescribes a series of stretching exercises, ice to the involved area, and rest. You are intrigued by the diagnosis. Upon your return home, you log on to the internet and begin a search for information about piriformis syndrome. When you type the words into your favorite search engine, you immediately get 2,780,000 results in response to your query.

Your use of the internet to seek health information mirrors the behavior of many consumers who are increasingly relying on the internet for health-related information. The challenge for consumers and healthcare professionals alike is the proliferation of information on the internet and the need to learn how to recognize when information is accurate and meaningful to the situation at hand.

This chapter explores consumer information and education needs and considers how patient engagement and connected health technologies, including new trends in wearable technology, may help to meet those needs yet at the same time create ever-increasing demands for health-related information. It begins with a discussion of health literacy, eHealth, and health education and information needs and explores various approaches by healthcare providers to using technology to promote health literacy. Also examined is the use of games, web quests, and simulations as a means of increasing health literacy among the school-age population. Issues associated with the credibility of web-based information and barriers to access and uses for patient engagement are discussed. Finally, future trends related to technology-supported consumer information and connectivity are explored.

Consumer Demand for Information ⬆ ⬇

This is the Knowledge Age; most people want to be in the know. People demand news and information and want immediate results and unlimited access. The same is increasingly true with health information. More and more people, in a trend known as consumer empowerment, patient engagement, and connected health, are interested in partnering with healthcare providers to take control of their health. These patients are not satisfied with being dependent on a healthcare provider to supply them with the information they need to manage their health. Instead, they are increasingly embracing electronic technologies, such as patient portals, to offer current and past health statuses, lab results, and secure messaging with providers; social media interactions; health-related games; wearable technologies for tracking health; and health management apps. Refer to Box 16-1 to review three apps and reflect on how nurses can engage with and connect their patients to their own health, whether it be diet and exercise help; medication support; or something specific to their contextual situation, such as pregnancy or monitoring their heart's function.

| Box 16-1 Mobile Apps: Applications to Connect and Engage Patients |

|---|

| Mobile apps are software programs that operate on smartphones and other mobile communication devices. They can also be accessories that connect to a smartphone or other mobile communication device. Given these definitions, they can be a combination of accessories and software. There are mobile apps for health and medicine that patients use to manage their own health and wellness. According to Edwards, in 2019, there were over 97,000 health and fitness apps on the market, 15% of 18- to 29-year-olds have installed health-related apps on their smartphones, 8% of 30- to 49-year-olds have installed medical apps, 40% of physicians said these tools can decrease the number of face-to-face clinical visits, and 93% of physicians believed that mobile apps can improve the quality of patient health. The fitness app market grew 45% in 2020, and unique users reached 385 million in 2021 likely as a result of the pandemic (Curry, 2023). Mobile apps have a place in the delivery of health care because they help to engage patients with their own health, wellness, and overall health status. These apps not only engage but can also empower patients to actively contribute to and participate in their health care. |

| The Bump |

|---|

| The Bump (www.thebump.com) provides pregnancy and parenting information. It reviews planning a family, each trimester of pregnancy, and parenting. |

| Medisafe |

|---|

| Medisafe (www.medisafeapp.com) is a personalized medication reminder app for each medication a person is taking and also provides drug interaction warnings. You can list caregivers as Medfriends, and the app will send them notifications if you miss a medication. Easily share the medications you are taking with your healthcare provider because they reside on your smart device. |

| KardiaMobile |

|---|

| KardiaMobile (www.alivecor.com/kardiamobile) is an app with a battery-operated device that has two pads; lightly place your index and middle fingers from one hand on one pad and your index and middle fingers from the other hand on the other pad. This device is 3.20 inches (8.2 cm) by 1.25 inches (3.2 cm) by 0.14 inches (0.35 cm) with two 1.18-inch (3 cm) by 1.18-inch (3 cm) stainless steel electrodes. To use this device, you must place it near your smartphone, open the app on your smartphone, and choose record. Your EKG is visible on your smartphone and is recorded and saved to be shared with healthcare providers. You will see your results after a 30-second recording and receive a personalized heart health report every 30 days with a summary of your EKG and blood pressure readings to share with your healthcare provider. This mobile app is an example of a combination of accessories and software.

|

A national survey by the Pew Research Center's Internet and American Life Project (Fox & Duggan, 2013) indicated that 8 in 10 Americans who are online have searched for health information (these numbers are comparable to the numbers in previous surveys conducted in 2006 and 2011). The most frequent health topic searches (69%) were related to a specific disease or medical problem that the searcher or a member of the family was experiencing. Other frequent topics of health-related searches were weight, diet, and exercise (60%) and health indicators, such as blood parameters or sleep patterns (33%). The 2011 survey (n = 3,001) indicated that consumers also searched for information on food (29%) and drug safety (24%; Fox, 2011). Just over half of “online diagnosers” (i.e., those who search online for information about medical conditions) reported that they shared their internet findings with their healthcare providers, and 41% reported that their findings were confirmed by a clinician (Fox & Duggan, 2013). It is clear that patients are increasingly looking to be partners with their healthcare providers in managing their health challenges and maintaining a level of wellness. Stansberry et al. (2019) studied 530 participants. The majority of their comments surrounded their hopes and concerns over technological changes occurring in their lives; they referred to technological advances such as “brain-computer interfaces, virtual immersive experiences that will teach and entertain users, pervasive connectivity linked to artificial intelligence (AI) that helps people navigate the world and understand it better, and predictive and personalized applications that make life easier” (para. 1). Carmona et al. (2022) collected data on 2,437 users of a web-based symptom checker using AI-Buoy Health. They reported that over half of the users had pain, a lump or mass, or a gynecological issue, and many were directed to seek care within a week or to self-care. “The results of this study demonstrate the potential utility of a web-based health information tool to empower people to seek appropriate care and reduce health-related anxiety” (p. 15). Box 16-2 provides an overview of AI as a patient engagement strategy.

| Box 16-2 Artificial Intelligence (AI) Applied as a Patient Engagement Strategy |

|---|

| In today's competitive and confusing healthcare delivery system, it is important that providers be able to personalize each patient's experience. Open communication is key to remaining current with the needs of patients while making them feel connected to the practice and satisfied with the care they receive. In a blog post on Seismic (2017), it was stated that “[w]hen it comes to patient engagement, the promise of AI is to improve the experience by anticipating patient needs, providing faster and more effective outcomes” (para. 7). Seismic recommended the following: |

- Engaging patients with insights that are conversational and contextual, and adjusting based on the situation to respond in real time.

- Teaming providers with the intelligent guidance of AI so they can provide patients with next-best actions, personalized to them.

- Empowering patients who want to actively participate and engage in their health with intelligent guidance and support when needed. (para. 7)

The blog post stated it best: A smart machine might be able to diagnose an illness and even recommend treatment better than a doctor; however, it takes a person to sit with a patient, understand their life situation, and help determine which treatment plan is optimal. (para. 9) Heath (2019) stated that a “survey of 2,000 healthcare consumers and 200 business decision makers (BDMs) revealed that AI may soon be the future of patient care” (para. 2). AI must not only engage patients but also engage healthcare providers and facilitate their ability to provide healthcare. Marr (2018) stated that AI can help with critical thinking, clinical judgment, image analysis, robotic-assisted surgery, and diagnosing. He also described providing virtual nursing assistants to monitor patients and facilitate communication and information exchange between face-to-face visits. Heath (2018) discussed the high patient satisfaction scores when patients are provided virtual care: “[F]orty-seven percent of patients said they prefer a more immediate, virtual care encounter than having to wait for an encounter that is in person” (para. 7). AI in the form of virtual nursing assistants can help patients feel connected and engaged in their care. Reflect on the following AI virtual patient encounter; assume each role (nurse, Craig, and patient, Mary), and assess your perspective as each one. The AI virtual nurse is known as Kate. |

| AI Virtual Patient Encounter Scenario |

|---|

| Mary has an appointment at the nurse-managed clinic next week but has questions about how she is feeling now. Mary grabs her tablet; opens the virtual AI app; and reaches out to Kate, her virtual nurse.

Kate is an intelligent virtual nurse who appears as an avatar. She is powered by AI and is continuously learning about her assigned patients from both the patients and the nurses with whom she interacts frequently. Kate receives Mary's call and immediately reviews her information:

Mary has been in what she classifies as “great health” all her life until now, “hitting 45 did me in.” She is a 45-year-old woman who has never married and was steeped in her career as an architect, for which she traveled 3 weeks out of every month. She had a myocardial infarction last month and has since been afraid to assume her activities of daily living and is terrified of going back to work. She reaches out at least once per day and submits monitoring data every 3 to 4 hours, at least 5 times per day. Her EKG monitoring device works through her smartphone and records her EKG, blood pressure, pulse, and respirations.

Kate has been monitoring Mary's submissions and notices that she is tachycardic generally once per day in the evening but not the other four times she submits her EKGs and vital signs. Kate had a discussion with Mary's nurse, Craig, last week. Craig had a cardiologist review the EKGs to make sure everything was fine. The cardiologist did not find an issue with the EKG but wanted to know more about the tachycardia since it occurs only once daily. Craig shared the results from the cardiologist's assessment with Kate. Craig also asked Kate to correlate Mary's activities so that they could determine what is occurring in the evening when she becomes tachycardic since all the other vital sign submissions are within normal limits. Kate reported to Craig that the tachycardic episodes correlate to when Mary's mom leaves to go home for the night.

Kate responds in fewer than 15 seconds to Mary's call and says, “Hello, Mary. What can I do for you?”

Mary says she will submit her monitoring information since she feels like her heart is beating fast this afternoon.

Kate tells Mary that she has received the data and to please wait a moment while she reviews it. It is immediately evident that Mary is tachycardic. Kate asks Mary all the appropriate questions related to assessing whether the tachycardia is of concern. She determines that it is not of concern at this time.

Mary states that she is not feeling dizzy but that she feels her heart race at least once a day: “It scares me!”

Kate asks whether her mom is still there since it is early afternoon.

Mary states that her mother just left.

Kate remembers that Craig wanted her to ask Mary more detailed questions surrounding when her mother leaves. Kate begins questioning Mary about what she has been doing for the past hour and exactly when her mother left.

Mary tells Kate that the only thing she's done is drink the big cup of hot chocolate that her mom had made her before she left and that she had to leave early today. “She takes such good care of me and always leaves me with a magazine and a cup of hot chocolate.”

Kate asks her to resend a set of vital signs, including EKG, in two hours. Kate also asks Mary whether she has any other questions or needs anything else at this time.

Mary says that she is fine and will send in her information in 2 hours.

Kate reaches out to Craig and informs him of the hot chocolate Mary's mom makes when she is getting ready to leave her. Craig thanks Kate for the information and asks her to continue to monitor Mary's EKG and vital signs.

Mary complies and submits her requested data to Kate.

Kate reviews the information Mary has sent and determines that everything is normal. She calls to let Craig know.

Craig reaches out to Mary to assess her caffeine intake throughout the day and to verify that she feels OK since her vital signs and EKG indicate that she is doing well.

Mary states that she does not knowingly have any other caffeinated foods or drinks throughout the day. She says her “mother is going to be very upset since she is the one causing me to race.”

Craig answers all Mary's questions and assures her that Kate will continue to monitor her and is readily accessible if she needs anything when Craig is not available.

Craig then calls Kate and has a discussion with her about asking dietary questions and following up on what is occurring in the patient's situational context around variations noticed in EKGs and vital signs with their cardiac patients.

Kate is still learning, and the time Craig spends with her helps to hone her skills and ability to assess and help their patients.

It is important to note that Kate's developer, a nurse informaticist, required social context and patient feelings/insights as required information for the AI virtual nurse to receive and assess in addition to the healthcare data and information related to the patient's health, illness, or care needs.

As the patient, would you want to interact with Kate? Describe your answer.

As the nurse, answer the following questions:

|

- Would you trust Kate to interact with your patients?

- How much time would you be willing to spend to help Kate learn?

- How would you assess Kate's performance and growth over time?

- Would you be interested in working with the AI developers to better understand her capabilities, make suggestions, and further enhance Kate's abilities?

Where do you believe AI capabilities will be in 5 years? How about in 10 years? |

All healthcare professionals must be prepared to listen to their patients' ideas about their personal health and at the same time provide direction toward credible health information supplied by electronic provider portals on the internet. Here is some good news: In an attempt to improve the credibility of the results of online searches about health, in 2015 Google partnered with the Mayo Clinic to fact check the information in a database for 400 of the most commonly searched for health issues (Lapowsky, 2015). According to Dr. Pearl (2019), algorithms must be altered to help differentiate good sources from those providing misinformation, credible sources should accept direction and assistance from the healthcare community, and warnings should be added to websites that are sharing unsafe or dangerous health information. Healthcare is different from other industries. Dr. Pearl makes a distinction about the ability of consumers reading sales ads or information from other sites: “When most shoppers come across a Rolex watch selling for $19.99 online, they know it's a scam. But when it comes to medical information, many patients and parents don't have the scientific expertise to discern what's real from fake” (para. 13). Medical misinformation exploded on the internet during the COVID-19 pandemic. Shajahan and Pasquetto (2022) stated, “Countering misinformation requires addressing long-standing challenges that operate within social, psychological, economic, technological, and political dynamics” (p. 124). They were part of a team that developed a misinformation toolkit for providers, MisinfoRx. They suggest that when patients present inaccurate information that they found on the internet that providers acknowledge the health information-seeking behavior and then gently correct misinformation. They also caution about commenting or arguing on misinformation posts on the internet, as this boosts the post. Rather, if providers have an online presence, they should seek to post accurate information and to like or share the accurate posts of others.

It is important to note that surveys of online health behaviors are limited to those individuals who are online; therefore, they do not reflect the health information needs or demands of those persons who are not online. Digital divide is the term used to describe the gap between those who have and those who do not have access to online information. Nurses and healthcare providers must be aware of the various components of the digital divide to ensure that patients and clients are receiving the health information they need in a format that they are interested in and can comprehend. Notably, persons with chronic diseases are less likely to have internet connectivity. Fox and Purcell (2010) explained that having a chronic disease is associated with age, level of education, ethnicity, and income-all factors that are also associated with the digital divide. Persons living with a chronic disease who have internet access are likely to use the internet for blogging and online discussion forums, activities popularly referred to as peer-to-peer support. An issue brief by the Council of Economic Advisers (2015) reiterated digital divide factors as age, education, income, and geographic location. In 2021, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration released a countrywide interactive map of the digital divide (www.ntia.gov/press-release/2021/ntia-creates-first-interactive-map-help-public-see-digital-divide-across-country). By providing infrastructure investment monies, the ConnectED initiative was designed to increase broadband access for schools. A similar initiative is designed to promote competition among internet providers, thereby lowering costs and making high-speed internet connections more affordable and accessible across the country. One of Healthy People 2030's overarching goals remains “Eliminate health disparities, achieve health equity, and attain health literacy to improve the health and well-being of all” (HealthyPeople.gov, n.d., para. 1). Thobias and Kiwanuka (2018) stated that there are challenges and barriers to information dissemination in low-resource settings in their study. One area was the lack of access to phones for mothers. They presented a data model that would leverage the leaders in the community who owned smartphones and others, including relatives, to assist with transmitting health education messages to the mothers. Their study has shown the feasibility of using phones to communicate with mothers who do not actually own phones. This is a great example of providing technologies that work with the constraints of the situation. Another example of addressing the digital divide is the growing number of health-related websites that support Spanish and other language formats.

Health Literacy and Health Initiatives ⬆ ⬇

The goal of health literacy for all is one that is widely embraced in many sectors of health care and remains an overarching goal for Healthy People 2030 (Health.gov, n.d.). Clinicians who have been practicing for some time recognize that informed patients have better outcomes and pay more attention to their overall health and changes in their health than those who are poorly informed. Some of the earliest formally developed patient education programs, which included postoperative teaching, diabetes education, cardiac rehabilitation, and diet education, were implemented in response to research that suggested the positive effect of patient education on health outcomes and satisfaction with care.

The Health Resources and Services Administration (2022) concluded that those persons with low health literacy have difficulty understanding what healthcare providers are telling them, lower educational skills, cultural barriers to health care, and issues managing chronic illnesses. Low health literacy affects the incidence and management of disease. “Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others” (para. 1). For example, healthcare providers depend on a patient's ability to understand and follow directions associated with dietary restrictions or exercising at home. It is also assumed, sometimes erroneously, that people will correctly interpret symptoms of a serious illness and act appropriately. Locating and evaluating health information for credibility and quality, analyzing the various risks and benefits of treatments, and calculating dosages and interpreting test results are among the tasks that are essential for health literacy. Other important and less easily learned health literacy skills are the ability to negotiate complex healthcare environments and understand the economics of payment for services.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH; 2021) reported that numerous studies concerning health literacy demonstrate that a variety of challenges remain on both the patient and the healthcare provider sides of the equation. This is still true today, as evidenced in the Healthy People 2030 overarching goals. Health.gov (2016) created a health literacy online guide that was last updated in 2016 but that still contains valuable information, such as the Health Literacy Online Strategies Checklist. According to Health.gov (2021), “Health literacy and clear communication between health professionals and patients are key to improving health and the quality of health care” (para. 1).

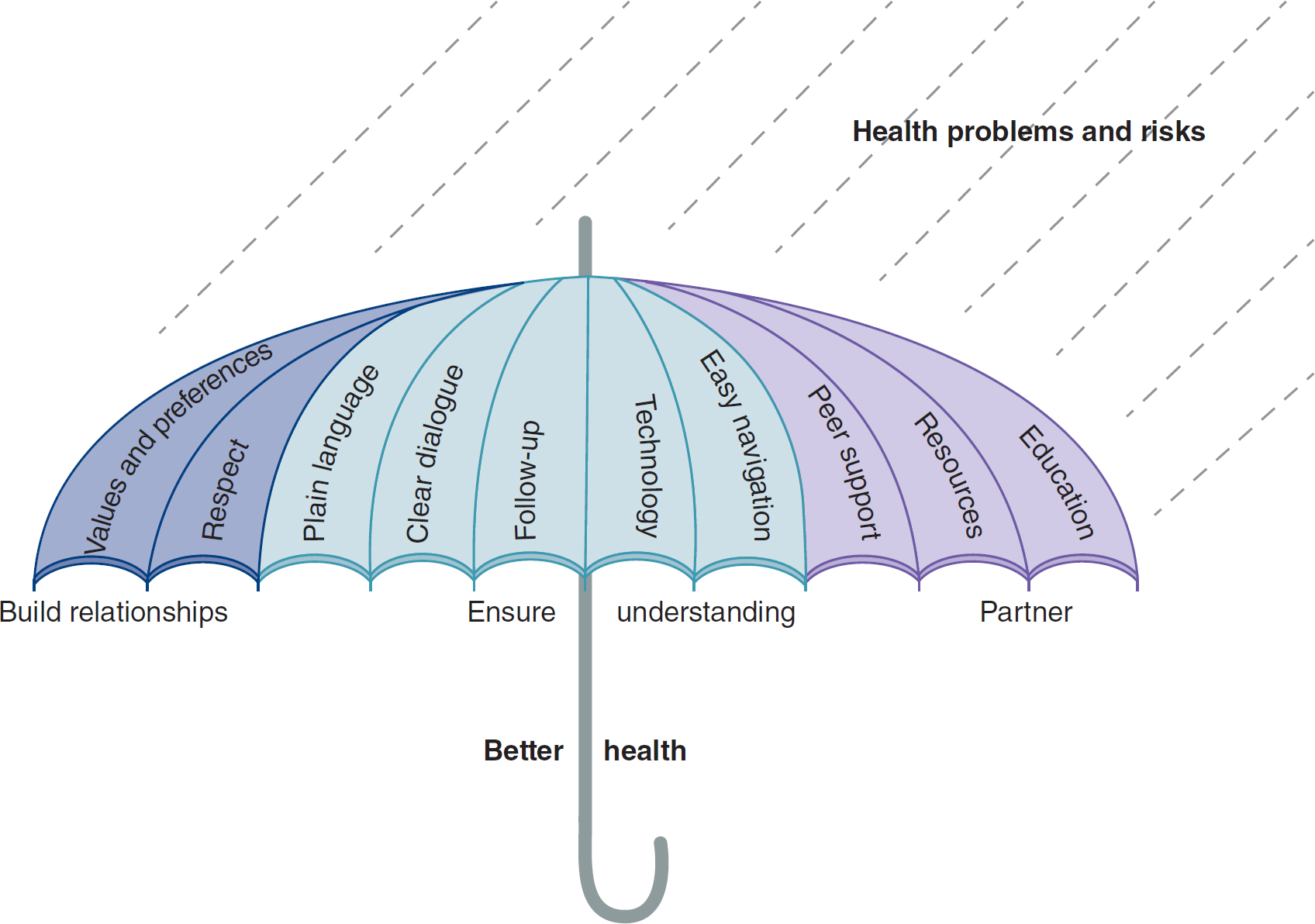

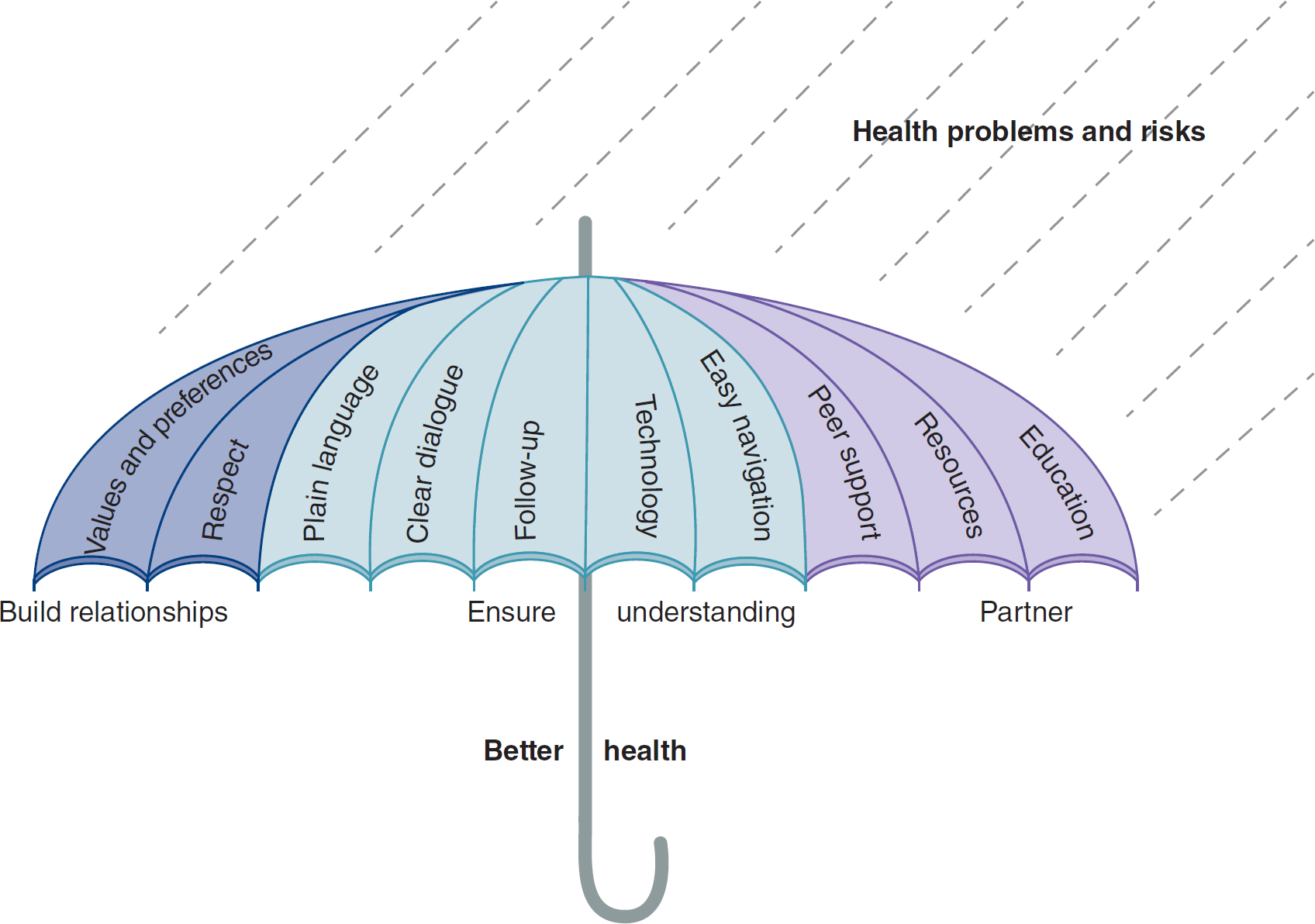

It is increasingly clear that better outcomes result when patients are well informed and engaged in their care. As depicted in Figure 16-1, there are a number of effective strategies to promote better health, including strategies for building sound relationships, strategies to ensure that patients are well informed about their health challenges, and strategies to build partnerships with patients.

Figure 16-1 The Health Literacy Umbrella

An umbrella under the rain symbolizes the health literacy umbrella.

The rain symbolizes health problems and risks. The umbrella encompasses key elements, including building relationships with values and preferences, and respect; ensuring understanding through plain language, clear dialogue, follow-up, technology, and easy navigation; and partnering with peer support, resources, and education. Underneath the umbrella, the concept is associated with achieving better health.

Developed by the Health Literacy in Communities Prototype Faculty: Connie Davis, Kelly McQuillen, Irv Rootman, Leona Gadsby, Lori Walker, Marina Niks, Cheryl Rivard, Shirley Sze, and Angela Hovis with Joanne Protheroe and the Ministry of Health, July 2009. IMPACT BC, with funding from the BC Ministry of Health.

The eHealth Initiative was developed to address the growing need for managing health information and promoting technology as a means of improving health information exchange, health literacy, and healthcare delivery. Visit the eHealth Initiative website (www.ehidc.org) for information. Although its scope goes beyond health literacy, a major goal continues to be empowering consumers to understand their health needs better and to act appropriately to those needs. The eHealth Initiative recently released a 2020 road map outlining a vision toward patient-centric care. Poor interoperability among healthcare systems and failure to embrace national data standards for health care continue to be identified as barriers to the eHealth Initiative. Further, concerns about privacy and security of information and the failure to invest appropriately in technology have slowed the development of this important initiative. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; 2023b) provides access to health literacy and eHealth initiatives by state (www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/statedata/index.html).

Healthcare Organization Approaches to Engagement ⬆ ⬇

Healthcare organizations (HCOs) use a wide variety of approaches and tools to engage patients and promote patient education and health literacy. Although the old standby for disseminating information is the paper-based flyer, some HCOs are recognizing that today's consumers are more attracted to a dynamic medium rather than to a static medium. In addition, the cost of designing and printing pamphlets and flyers becomes prohibitive when one considers the rapidity of changing information; the brochure may be outdated almost as soon as it is printed. One approach to deal with these issues is to have patient education information stored electronically so that changes can be made as needed or information can be better tailored to the specific patient situation and then printed out and reviewed with the patient.

Another old standby approach that is still widely used is the group education class. These classes initially were developed to help people manage chronic health problems (e.g., diabetes) and were typically scheduled while people were hospitalized. Now many HCOs also sponsor health promotion education classes as a way of marketing their facilities and showcasing their expert practitioners.

The movement from static to dynamic presentations began in many HCOs with the use of videotapes and then DVDs, which were shown in groups or broadcast on demand over dedicated channels via a television in patients' rooms. HCOs are now also taking advantage of the fact that patients and families are captive audiences in waiting rooms by promoting education via pamphlet distribution, health promotion programs broadcast on television, and health information kiosks in those locations. The kiosks are typically computer stations and often contain a variety of self-assessment tools (especially those related to risks for diabetes, heart disease, or cancer) and searchable pages of information about specific health conditions. The self-assessment tools represent yet another step forward in technological support for education; in addition to being dynamic, the kiosk is interactive. On the assessment page, the user is asked to respond to a series of questions and then the health risk is calculated by the computer program. One caution, however, is that just because the information is made available does not mean that people will participate or understand what they have experienced. Issues related to the level of health literacy, the digital divide, and the gray gap (i.e., differences in electronic connectivity by age) still exist in these situations.

Many HCOs have invested time and money in developing interactive websites and believe that web presence is a critical marketing strategy. Consider how the information in Box 16-3 might be attractive to a consumer. Most websites offer physician search capabilities, e-newsletters, and call-center tie-ins. As with all patient education materials, there must be a sincere commitment to keeping information current and easily accessible. Web designers must pay particular attention to the aesthetics of the site, the ease of use, and the literacy level of those in the intended audience.

| Box 16-3 The Science Fiction-Reality Factor |

|---|

| It is true that we want to have a health-literate and truly engaged patient to partner with their healthcare journey. It is a stretch at times for patients to comply with or understand their treatment plan and/or medication regimen. Inc. (2018) brought a new level to literacy and engaging patients and their significant others or caregivers. It provided the following example of sci-fi meeting reality when it stated that “3D printing is a cutting-edge innovation in health care today” (para. 5). It can be used to generate casts, and “some scientists are now experimenting with 3D-printing organs” (para. 5). |

| Application |

|---|

| What if a “child needs a prosthetic hand-printing it at home could drastically lower the cost” (Inc., 2018, para. 6) as well as decrease the time to receive the replacement.

Reflect on how health literate and engaged the parents and/or caregiver must be to accomplish this task.

|

The aim of the review conducted by Reen et al. (2019) was “to synthesize the usability of specific health information websites” (para. 2). They provided insights into how to assess website usability. It is important to collect information on user site preferences and user satisfaction with websites. “Preferred website features were interactive content such as games and quizzes, as well as videos, images, audio clips, and animations” (para. 4). When considering the adolescent population, it was important for them to be able to communicate or interact with other like adolescents, and they wanted to learn about their situation by hearing true stories in other adolescents' own words.

The rapid growth of electronic communication through increased use of computers and access to the internet, particularly for medical purposes, empowers the clinician as well as the consumer of healthcare information. The integration of information and communication technologies and the growing trend of consumer empowerment have reshaped the delivery of health care. As a result of meaningful use initiatives, many HCOs have developed secure patient portals that allow patients to access their health records, including tracking laboratory results and reviewing the records. Most HCOs, however, do not allow patients to edit these records. In addition, patients are occasionally interested in interacting with others who have the same or similar conditions, and some HCOs are providing the information necessary to help them connect. This peer-to-peer support is especially popular with patients who have cancer diagnoses, diabetes, and other chronic and debilitating conditions (Lober & Flowers, 2011).

Some HCOs are using social media for health education to promote actual engagement of audiences rather than as a means of one-way messaging. Neiger et al. (2013) suggested “that the use of social media in health promotion must lead to engagement between the health promotion organization and its audience members, that engagement must provide mutual benefit, and that an engagement hierarchy culminates in program involvement with audience members in the form of partnership or participation (as recipients of program services)” (p. 158). The CDC (2011) has an excellent social media tool kit that can be used by health educators to guide the planning and implementation of social media strategies for health promotion: www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/ToolsTemplates/SocialMediaToolkit_BM.pdf. The CDC (2023a) also has a social media overview page at www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/toolstemplates/socialmediatoolkit_bm.pdf. The CDC (2023a) also has a digital and social media page at www.cdc.gov/digital-social-media-tools/index.html.

Promoting Health Literacy in School-Age Children ⬆ ⬇

Promoting health literacy in school-age children presents special challenges to health educators. There is wide agreement that childhood obesity is a serious and growing issue, which is related not only to poor choice of foods but also to the sedentary lifestyles promoted by video games and television. In addition, the time once devoted to health and physical education programs in schools has given way to more time spent on core subjects, such as math and science. Auld et al. (2020) recommended strategies to support health-enriching behaviors, such as customizing and personalizing information and engaging students using age and developmentally suitable information, materials, teaching techniques, and learning approaches. The eHealth programs are developed specifically to appeal to the generational (i.e., highly connected and computer literate) and cultural needs of this group.

Although sedentary lifestyles promoted by video game engagement may contribute to obesity, gaming may be an effective way to promote health literacy. Here are a few examples and an overview of very early games. As early as 2005, Donovan described an interdisciplinary web quest designed to appeal to older school-age children. The quest is interdisciplinary in that it requires reading comprehension, critical thinking, presentation, and writing; thus, core skills and health literacy skills are learned in a single assignment. Students are directed to the web to search for information on the pros and cons of low-carbohydrate diets and obesity prevention. Students learn along the way as they search for information, collect and interpret it, and then develop a presentation and final paper.

The Cancer Game (Oda & Kristula, n.d.) was developed by a young man taking a college class on Macromedia software who had previously undergone a bone marrow transplant. Subsequently, he and a professor collaborated and expanded the project to its present form. The game is designed as an arcade-style video game for cancer patients to relieve stress by visualizing the fighting of cancer cells. Although cancer victims of any age can access and play the game, it has a special appeal to children and adolescents. Similarly, Ben's Game (https://archive.org/details/bensgame) is a video game designed to help relieve the stress of cancer treatment for children (Anderson & Klemm, 2008). According to Cullen et al. (2016), Squires Quest II is a serious video game designed to increase fruit and vegetable consumption in fourth and fifth graders; these authors found an increase in fruit intake at breakfast and increased vegetable intake at dinner. This is a great example of a health education program designed to appeal to this connected generation of learners and their intuitive ability to use interactive technologies.

You can access newer games on the internet by typing “health games” into a search engine. Be sure to review the information presented in the game for accuracy before you recommend it to parents and children. The National Library of Medicine maintains a site dedicated to health learning games for both children and adults (https://medlineplus.gov/games.html). You can feel confident in recommending games from this trusted website because it has been vetted for accuracy and credibility.

Winkelman et al. (2016) reported that only 12% of adults in the United States are proficient in health literacy, or the ability to successfully navigate and function in the healthcare system. This is cause for grave concern because health literacy is one of the strongest predictors of health; it is more prognostic than gender, age, income, or educational status (Leiditch, 2021). Low health literacy is linked with poor child health outcomes, increased healthcare costs, and higher mortality rates (Schools for Health in Europe, n.d.; Winkelman et al., 2016). It is easy to understand why the CDC (2022) has a website on health literacy to support schools (www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/education-support/schools.html) and why health literacy was included in Healthy People 2010 and Healthy People 2020 and continues as a goal in Healthy People 2030.

Supporting Use of the Internet for Health Education ⬆ ⬇

Nurses and other healthcare providers must embrace the internet as a source of health information for patient education and health literacy. Patients are increasingly turning there for instant information about their health maladies. Health-related blogs (short for weblogs, or online journals) and electronic patient and parent support groups are also proliferating at an astounding rate. Clinicians need to be prepared to arm patients with the skills required to identify credible websites. They also need to participate in the development of well-designed, easy-to-use health education tools. Finally, they need to convince payers of the necessity of health education and the powerful effect education has on promoting and maintaining health. Box 16-4 provides more information about patient education.

| Box 16-4 Considerations for Patient Education |

|---|

| Julie A. Kenney IdaAndrowich

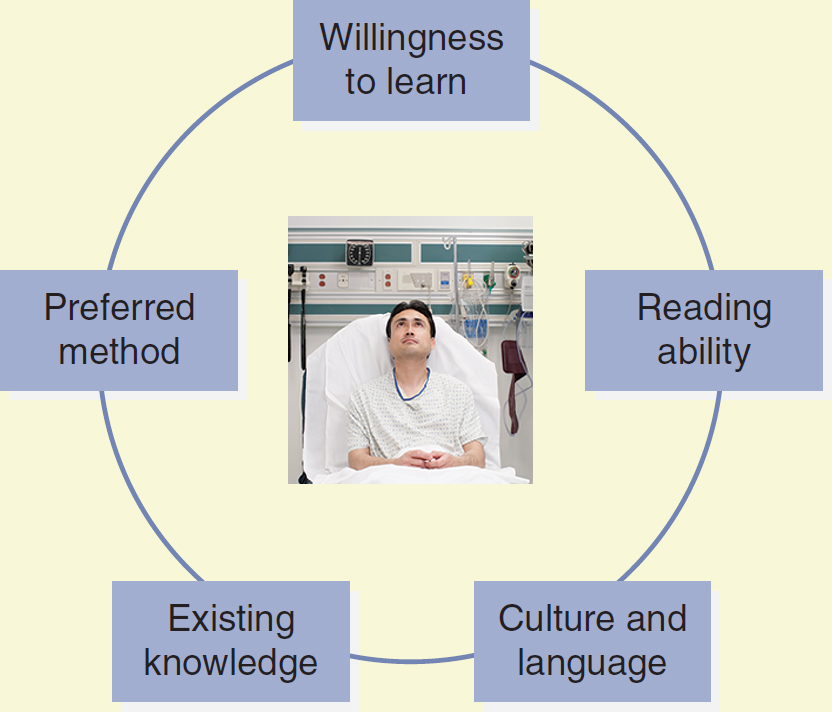

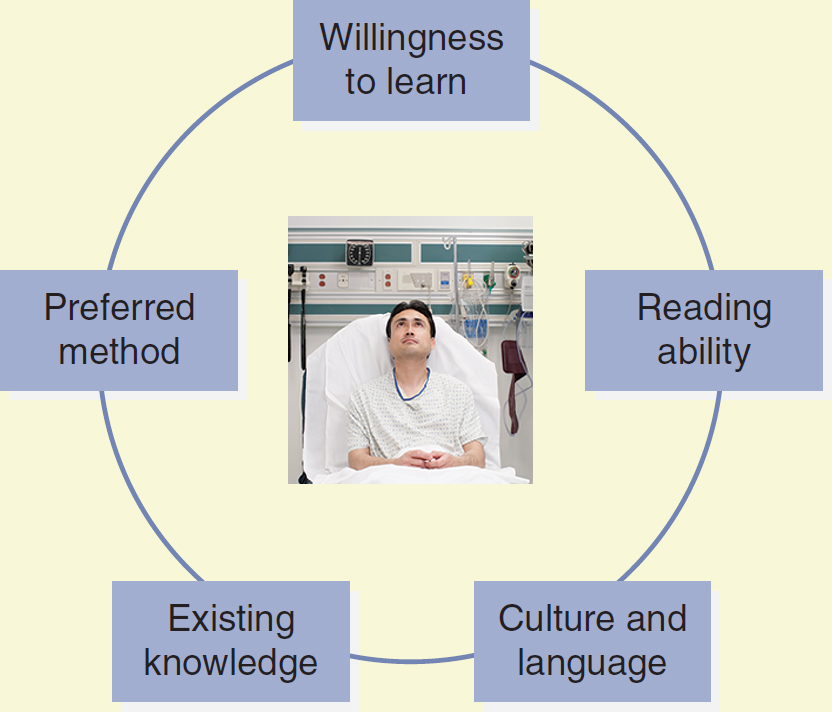

Nurses need to consider many things when teaching patients. They need to assess patients' willingness to learn and reading ability, the means by which they learn best, and their existing knowledge about the subject. These important considerations for patient education are depicted in Figure 16-2.

Figure 16-2 Choosing an Education Strategy

A cyclic diagram depicts the considerations in choosing an education strategy. Elements include willingness to learn, reading ability, culture and language, existing knowledge, and preferred method.

Photo: © ERproductions Ltd/Blend Images/Getty Images

Nurses also need to consider cultural, language, and generational differences when teaching their patients. If the nurse chooses to use an electronic method to educate the patient, digital natives (i.e., patients who have grown up with technology) need to be taught differently from digital immigrants (i.e., those who are late adopters of technology; “Educational Strategies,” 2006). Digital natives are typically born after 1982 and may also be referred to as Millennials. This generation prefers to learn using technology and learns quite well if information is presented in a format to which they are accustomed, such as an interactive video game to introduce them to a topic. This group is also comfortable using information that they can access via their handheld devices, such as smartphones and tablets, as well as wearable devices, such as smartwatches. Those born before 1982 have learning styles that range from preferring to learn in a classroom setting to reading a book about the topic to learning using a hands-on, interactive approach (“Educational Strategies,” 2006).

A systematic review of the literature related to teaching methods (Friedman et al., 2011) suggested that all the various modalities ranging from computer technologies to demonstrations and reviews of written materials can be effective as long as they are structured and specifically designed for and congruent with the patient's culture. More recently, Sawyer et al. (2016) tested a tablet-based education program for patients with heart failure. They sought to demonstrate the value of the tablet-based education approach to staff and at the same time find ways to minimize the disruptiveness of the technology-based education on clinical workflow, ensure patent safety by establishing specific procedures for device cleaning, and suggest strategies for maintaining the security of the devices. They conclude that technology-based learning tools may be effective in helping patients manage their disease after discharge. They also emphasize the need to consider clinician workflow and device security to ensure a successful implementation.

The next generation, Generation Z, are those born between 1996 and 2010 (Spitznagel, 2020). This generation is growing up in a highly sophisticated and complex digital environment and spending more time with digital devices and the internet than the previous Generation Y. They are also the most ethnically and racially diverse. These individuals are active problem solvers and comfortable and familiar with getting information on demand. They do not like lectures and expect to be able to customize their educational episodes. The teaching strategies should fit with the patient's culture and include using up-to-date instructional technologies, including communication and feedback incorporating social media and smart devices.

References - Educational strategies in generational designs. (2006). Progress in Transplantation, 16(1), 8-9. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/152692480601600101

- Friedman A., Cosby R., Boyko S., Hatton-Bauer J., & Turnbull G. (2011).

Effective teaching strategies and methods of delivery for patient education: A systematic review and practice guideline recommendations.

Journal of Cancer Education, 26, 12-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-010-0183-x - Sawyer T., Nelson M. J., McKee V., Bowers M. T., Meggitt C., Baxt S. K., Washington D., Saladino L., Lehman E. P., & Brewer C. (2016).

Implementing electronic tabletbased education of acute care patients.

Critical Care Nurse, 36(1), 60-70. https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn2016541 - Spitznagel E. (2020).

Generation Z is bigger than millennials-And they're out to change the world.

New York Post. https://nypost.com/2020/01/25/generation-z-is-bigger-than-millennials-and-theyre-out-to-change-the-world/

|

The HONcode and TRUSTe accreditation symbols are two of the most common symbols that indicate trustworthy and secure websites. Internet users can also look at the domain name of the website as a clue to trustworthiness. Many users gravitate toward university sites (.edu), government sites (.gov), and HCO sites (.org). Remember that commercial sites (earn money from advertisers and seek to sell products or services) will use the (.com) domain name and may or may not have credible information to share.

The National Library of Medicine and the NIH jointly sponsor MedlinePlus (https://medlineplus.gov), a website that has a tutorial for learning how to evaluate health information and an electronic guide to web surfing that is available in both English and Spanish. A similar guide explains the major things one should evaluate when accessing health-related resources on the web (National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, 2018). Suggest that patients visit these sites to become more adept at identifying whether a website is credible before they adopt the recommendations provided.

Some healthcare professionals have partnered with their organizations to develop patient education materials. These materials must be carefully reviewed for accuracy and usability. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2014) published an assessment tool for both print and audiovisual patient education materials. Its tool is designed to assess both understandability and actionability by providing a series of review criteria for each of these domains. Clearly, clinicians need to engage patients to partner with them in the management of their health. Refer to Box 16-4 and Box 16-5 to review effective education methods used in teaching patients and their families about their health challenges.

| Box 16-5 A Clinician's View on Patient Education |

|---|

| Denise D. Tyler

Knowledge dissemination in nursing practice includes sharing information with patients and families so that they understand their healthcare needs well enough to participate in developing the plan of care; make informed decisions about their health; and, ultimately, comply with the plan of care, both during hospitalization and as outpatients.

There are several effective methods for educating patients and their families. One-on-one and classroom instruction are traditional and valuable forms of education. One-on-one education is interactive and can be adjusted at any time during the process, based on the needs of the individual patient or family; it can also be supplemented by written material, videos, and web-based learning applications. Classroom education can be beneficial because patients and families with similar needs or problems can network, thereby enhancing the individual experience. However, the ability to interact with each member of the group and tailor the educational experience based on individual needs may be limited by the size and dissimilarities of the group. Individual follow-up should be available when possible.

Paper-based education that is created, printed, and distributed by individual institutions or providers can be very effective because materials can be distributed at any time and reviewed when the patient feels like learning. Many agencies, such as the CDC, have education for patients available on their websites. These documents can be reviewed online or printed by healthcare providers or patients. Organizations can also develop and distribute information and instructions specific to their policies and procedures. In addition, printed educational material can be purchased from companies that employ experts in the subject matter and instructional design.

One of the more popular sources of patient education information is the internet. Many hospitals and HCOs provide proprietary information in this manner, such as directions to the facility, information on procedures, and instructions on what to expect during hospitalization. Other health organizations, such as the NIH, provide detailed information on their websites. Clinicians should be cautious when recommending websites to patients and families because not all sites are reliable or valid.

Many companies that provide clinical information systems or electronic health records also include patient education materials linked to the clinical system via an intranet. Thus, standardized instructions that are specific to a procedure or disease process can be printed from this computer-based application. Discharge instructions that are interdisciplinary and patient specific can often be modified via drop-down lists or selectable items that can be deleted or changed by the clinician. This ability to modify before printing provides more consistent and individualized instruction. The computer-based generation of instruction is preferable to free-text and verbal instruction because it also allows the information to be linked to a coded nursing language and therefore easily used for measurement and quality assurance reporting. Relevant triggers may be embedded in the clinical information systems. For example, when a patient answers yes to a question about current smoking, smoking cessation information should automatically be printed, or a trigger should remind the nurse to explore this topic with the patient and then provide the patient with preprinted information on smoking cessation.

Integration of standardized discharge instructions and patient education into the clinical system is another way to improve the compliance and documentation of education; it also streamlines the workflow of clinicians. Printing the information to give to the patient should be seamless to the clinician who is documenting information into the patient's record. The format should be logical and easy to read. The more transparent the process, the more efficient the system and the easier it is to use for the clinician. What I envision for the future is a system that “remembers” the style of learning preferred by patients and their families, prompts the provider to print handouts, and programs the bedside computer/video education system, based on previous selections and surveys. This interactive patient and family education would be integrated into the clinical system and the patient's personal health record.

|

Some providers have developed a list of credible websites and apps that are shared with patients or family members. Recommendations for websites might include the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services-sponsored MyHealthfinder site (https://health.gov/myhealthfinder), a website dedicated to helping consumers find credible information on the internet. Other excellent sources of reliable information are the NIH, the CDC, MedlinePlus, and the National Health Information Center (https://health.gov/our-work/health-literacy/resources/national-health-information-center). Some of the apps (found on iTunes for iPhones or Google Play for Android devices) that might be recommended include Mayo Clinic on Pregnancy, WebMD Pain Coach, MyFitnessPal, and Understanding Diseases. These are great examples of the wealth of patient information being developed as apps by hospitals and other healthcare providers. More apps are being developed every day to engage people in managing and taking control of their health. Perhaps the most important thing that healthcare professionals can stress is that not all apps have credible and valid information. We must encourage our patients to become savvy users of electronic information sources.

Future Directions for Engaging Patients ⬆ ⬇

Predicting future directions for technology-based health education is somewhat difficult because one may not be able to completely envision the technology of the future. One can predict, however, that some current technologies will be used increasingly to support health literacy and new technologies will be developed every day. For example, audio and video podcasts may become more commonplace in health education and be provided as free downloads from the websites of HCOs.

Voice recognition software used to navigate the web may reduce the frustration and confusion associated with attempting to spell complex medical terms. However, the confusion and frustration may increase if the patient or client is unable to pronounce the terms. Voice interactivity should help to reduce the digital access disparity associated with those who have limited keyboard or mouse skills. For those persons with visual impairments, some websites may provide both audio and text information and support increased text size for greater ease of reading (Anderson & Klemm, 2008).

Many websites associated with government and national organizations are also providing multiple-language access to health information and decision support tools (MedlinePlus, n.d.). The multilanguage access broadens the population to whom education can be provided, and the decision support programs allow users to access results that are tailored to their age, risk factors, or disease state (Anderson & Klemm, 2008).

As patient engagement strategies become more commonplace, we will also see a movement toward connected health. Those individuals who are frequent email users may be interested in being able to communicate with physicians and other healthcare personnel via email or a practice portal messaging system rather than the telephone. This idea previously met with some resistance from physicians who perceived email correspondence as bothersome and time-consuming. However, it is possible that work efficiency might increase if patients and their needs are screened via secure email or message before an office or a clinic visit. For example, as a result of an email correspondence in lieu of an initial office visit, medications could be changed or diagnostic tests could be performed before the office visit. In addition, patients could be directed to an interactive screening form housed on a secure website where they would answer a series of questions that would help them decide whether they should call for an appointment, head for the emergency room, or self-manage the issue. If self-management is the outcome of the screening tool, then the patient or caregiver could be directed to a credible website for more information. The idea is not to interfere with or replace the face-to-face visit but rather to supplement the provider-patient relationship and perhaps streamline the efficiency of healthcare delivery. Interestingly, Diaz (2022) noted that many physicians and healthcare systems are now billing for email correspondence if the correspondence required physician expertise and took more than 5 minutes.

Wearable technologies are becoming increasingly popular among tech-savvy patients. These technologies are promoting a paradigm shift from provider-centric to consumer-centric care.

The most common consumer-based wearables are fitness trackers, but there are no clear guidelines as to how to integrate the data these devices collect into a patient's health record and make them actionable.

Medgadget (2020) announced its breathable, stretchable, electronic fabric for new medical wearables that offers the “potential to monitor the body over extended periods of time in unprecedented ways. The heart's rhythms, flexion of joints, and other biomedical parameters can be tracked with high fidelity and continuously using devices that can conform to the body” (para. 1). The breathability is the key to the success of its product, with the electronics embedded into the stretchable material. This material permits gases “such as volatile organic compounds and sweat to come through thereby allowing it to be worn over the skin for many days” (para. 2). The more we can make our tools easy to comprehend and use, the more engaged and compliant our patients will be in their health and wellness journey. Virtual and augmented reality tools are increasingly being used for “stress relieving, relaxation, visualization, and guided meditation tools” (Polet, 2022, para. 3). The literature is beginning to reflect an expansion of concepts beyond patient engagement to enablement, empowerment, and action. LeRouge et al. (2022) stated that “the path to empowered activation includes healthy consumers' responses to critical personal assessments, leading to emergent states of engagement, enablement, and empowerment” (p. 2). They defined engagement as “individual motivation to participate in self-management behaviors”; enablement as “having appropriate knowledge, skills, and abilities to understand one's health condition and make decisions”; and empowerment as “a consequence of enablement and engagement and takes a form of an emergent state and process” (p. 3) leading to action.

Summary ⬆ ⬇

The healthcare delivery system is honing its engagement strategies for patient-centered, connected health. Hospitals are using social media to engage and connect with their patients. The consumer empowerment and connected health movement will continue to drive the need for access to quality health education, engagement, and support programs. In an ideal world, practitioners would design educational materials that are user friendly, culturally competent, interesting, dynamic, and interactive and that meet the skills, education needs, and interests of the user.

| Thought-Provoking Questions |

|---|

- Choose two patient engagement or connectivity tools and discuss specifically how you would use them to deliver care in your practice.

- Formulate a patient education plan for a common chronic health challenge related to your practice. Provide a rationale for each approach and describe a technology tool you would use to engage and educate the patient and their family.

- Reflect on connected health potentials in your practice. What are you doing currently that connects and engages your patients in managing their health? Describe in detail what you plan to do in the next 6 months to a year.

- Explore the Healthy People 2030 framework (https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/health-literacy-healthy-people-2030). How would you explain health literacy based on the 2030 goal? Determine and describe in detail several ways to promote health literacy across the life span.

|

References ⬆

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2014). The Patient Education Materials Assessment (PEMAT) and user's guide. www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/pemat_guide.pdf

- Anderson A., & Klemm P. (2008). The internet: Friend or foe when providing patient education? Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 12(1), 55-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1188/08.CJON.55-63

- Auld M. E., Allen M. P., Hampton C., Montes J. H., Sherry C., Mickalide A. D., Logan R., Alvarado-Little W., & Parson K. (2020). Health literacy and health education in schools: Collaboration for action. NAM Perspectives. National Academy of Medicine. https://doi.org/10.31478/202007b

- Carmona K. A., Chittamuru D., Kravitz R. L., Ramondt S., & Ramírez, A. S. (2022). Health information seeking from an intelligent web-based symptom checker: Cross-sectional questionnaire study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(8), e36322. https://doi.org/10.2196/36322

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). The health communicator's social media toolkit. www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/ToolsTemplates/SocialMediaToolkit_BM.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Health literacy: Schools. www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/education-support/schools.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023a). CDC social media.www.cdc.gov/digital-social-media-tools/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023b). Health literacy. www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy

- Council of Economic Advisers. (2015, July). Issue brief: Mapping the digital divide. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/wh_digital_divide_issue_brief.pdf

- Cullen K. W., Liu Y., & Thompson D. I. (2016). Meal-specific dietary changes from Squires Quest! II: A serious video game intervention. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 48(5), P326-P330. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2016.02.004

- Curry D. (2023, August 16). Fitness app review and usage statistics (2023). Business of Apps. www.businessofapps.com/data/fitness-app-market

- Diaz N. (2022, November 28). More health systems charging for MyChart messages. Becker's Healthcare. www.beckershospitalreview.com/ehrs/more-health-systems-charging-for-mychart-messages.html

- Donovan O. (2005). The carbohydrate quandary: Achieving health literacy through an interdisciplinary WebQuest. Journal of School Health, 75(9), 359-362. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.00050.x

- Fox S. (2011, February 1). Health topics. Pew Research Center. www.pewinternet.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/media/Files/Reports/2011/PIP_Health_Topics.pdf

- Fox S., & Duggan M. (2013, January 15). Health online 2013. Pew Research Center. www.pewinternet.org/2013/01/15/health-online-2013

- Fox S., & Purcell K. (2010, March 24). Chronic disease and the internet. Pew Research Center. www.pewinternet.org/2010/03/24/chronic-disease-and-the-internet

- Health.gov. (n.d.). Health literacy in Healthy People 2030.https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/health-literacy-healthy-people-2030

- Health.gov. (2016). Health literacy online: A guide for simplifying the user experience. https://health.gov/healthliteracyonline

- Health.gov. (2021). Health literacy. https://health.gov/our-work/health-literacy

- Health Resources and Services Administration. (2022). Health literacy. www.hrsa.gov/about/organization/bureaus/ohe/health-literacy/index.html

- Heath S. (2018, March 8). Patients welcome AI tech to create access to convenient care. PatientEngagementHIT. https://patientengagementhit.com/news/patients-welcome-ai-tech-to-create-access-to-convenient-care

- Heath S. (2019, February 19). Patients ready to embrace AI, patient engagement technologies. PatientEngagementHIT. https://patientengagementhit.com/news/patients-ready-to-embrace-ai-patient-engagement-technologies

- Inc. (2018, October 24). How technology is changing health care for the better.www.inc.com/aflac/changing-healthcare-for-the-better.html

- Lapowsky I. (2015, February 10). Google will make health searches less scary with fact-checked results. WIRED. www.wired.com/2015/02/google-health-search

- Leidich J. (2021, January 19). Improving adherence through patient health literacy. Hayes Hall Gazette. https://desis.osu.edu/seniorthesis/index.php/2021/01/19/improving-adherence-through-patient-health-literacy

- LeRouge C., Durneva P., Lyon V., & Thompson M. (2022). Health consumer engagement, enablement, and empowerment in smartphone-enabled home-based diagnostic testing for viral infections: Mixed methods study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 10(6), e34685. https://doi.org/10.2196/34685

- Lober W. B., & Flowers J. L. (2011). Consumer empowerment in health care amid the internet and social media. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 27(3), 169-182. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2011.04.002

- Medgadget. (2020, May 1). Breathable, stretchable electronic fabric for new medical wearables. www.medgadget.com/2020/05/breathable-stretchable-electronic-fabric-for-new-medical-wearables.html

- MedlinePlus. (n.d.). Health information in multiple languages.www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/languages/languages.html

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. (2018). Finding and evaluating online resources. www.nccih.nih.gov/health/finding-and-evaluating-online-resources

- National Institutes of Health. (2021). Clear communication: Health literacy. www.nih.gov/clearcommunication/healthliteracy.htm

- Neiger B. L., Thackeray R., Burton S. H., Giraud-Carrier C. G., & Fagen M. C. (2013). Evaluating social media's capacity to develop engaged audiences in health promotion settings: Use of Twitter metrics as a case study. Health Promotion Practice, 14(2), 157-162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839912469378

- Oda Y., & Kristula D. (n.d.). The Cancer Game: A side-scrolling, arcade-style, cancer-fighting video game. www.cancergame.org

- Pearl R. (2019, April 17). 3 ways to advance the credibility of online health information. KevinMD.com. www.kevinmd.com/blog/2019/04/3-ways-to-advance-the-credibility-of-online-health-information.html

- Polet D. (2022, January 19). 5 ways patient engagement technology is changing healthcare. Wellbe. https://wellbe.me/5-ways-patient-engagement-technology-is-changing-healthcare

- Reen G., Muirhead L., & Langdon D. (2019). Usability of health information websites designed for adolescents: Systematic review, neurodevelopmental model, and design brief. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(4): e11584. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/11584

- Schools for Health in Europe. (n.d.). Health literacy: Resources and glossary. www.schoolsforhealth.org/resources/glossary/health-literacy

- Seismic. (2017, May 30). The role of artificial intelligence in patient engagement. https://seismic.com/blog/the-role-of-artificial-intelligence-in-patient-engagement

- Shajahan A., & Pasquetto I. V. (2022). Countering medical misinformation online and in the clinic. American Family Physician, 106(2), 124-125.

- Stansberry K., Anderson J., & Rainie L. (2019, October 28). Themes about the next 50 years of life online. Pew Research Center. www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/10/28/themes-about-the-next-50-years-of-life-online

- Thobias J., & Kiwanuka A. (2018). Design and implementation of an m-health data model for improving health information access for reproductive and child health services in low resource settings using a participatory action research approach. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 18(45). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-018-0622-x

- Winkelman T., Caldwell M., Bertram B., & Davis M. (2016). Promoting health literacy for children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 138(6), e20161937. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1937