Objectives ⬇

- Explore the use of telehealth technology in nursing practice.

- Apply the Foundation of Knowledge model to home telehealth.

- Identify the socioeconomic factors likely to increase the use of telehealth interventions.

- Describe clinical and nonclinical uses of telehealth.

- Specify and describe the most common telehealth tools used in nursing practice.

- Explore telehealth pathways and protocols.

- Identify legal, ethical, and regulatory issues of telehealth practice.

- Describe the role of the telenurse.

Key Terms ⬆ ⬇

Introduction ⬆ ⬇

Telehealth refers to a wide range of health services that are delivered by telecommunications-ready tools, such as the telephone, videophone, smartphone, and computer. The telephone, the most basic of telecommunications technologies, has been used by health professionals for many years. For example, nurses may counsel a patient by telephone, or doctors may respond to patient status changes or family requests. Because of these widespread uses, people are already somewhat familiar with the value of the direct, expedient contact that telecommunications-ready tools provide for healthcare professionals. However, physicians and patients alike largely valued traditional face-to-face office visits because of the personal interactions they afforded. In addition, barriers to telehealth included reimbursement, connectivity, and equipment issues. Then, in March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic surfaced. Roth (2020) provided this insight: “With the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth has finally come of age. Like a lonely teenager who once struggled to make connections with a broader network of friends and was bound by strict parental controls, suddenly, telehealth has blossomed into the most popular kid in school by becoming an essential tool in the healthcare armament against this pandemic” (para. 1). Up until March 2020, Medicare beneficiaries were able to enjoy paid access to telehealth services only if they lived in a rural area and had certain chronic medical conditions. On March 13, 2020, President Trump announced widespread expansion of telehealth services for Medicare beneficiaries and relaxation of rules so that seniors could avoid exposure to COVID-19 in physicians' offices and clinics (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], 2020b) and virtual consultations could help triage patients for further treatment as necessary. As a result, the demand for telehealth and virtual visits increased exponentially, which taxed a system that was not prepared for this type of growth (Brodwin & Ross, 2020). Several key groups raced to provide the support and guidance that physicians, nurses, and healthcare systems would need to ramp up their telehealth services by using virtual platforms (i.e., Skype, WebEx, and Zoom), existing patient portals, messaging apps, or phone calls. For example, the American Hospital Association (AHA, 2020) released a best practices document, CMS (n.d.) released the General Provider Telehealth and Telemedicine Tool Kit, and the American Medical Association (AMA, 2023) released the AMA Telehealth Quick Guide (released in 2020 and updated in 2021), all in a matter of a few weeks.

In 2019, the AHA reported that 76% of hospitals used telehealth to provide some services and connect clinicians for consultations at a distance, up from 35% reported in 2010. At the time, the AHA also reported limitations on coverages for Medicare recipients; broadband limitations for patients in rural areas; cross-state licensing issues; and concerns about online prescribing, security, and privacy (AHA, 2019). The growth of telehealth services, prompted by necessity during the COVID-19 pandemic, is leveling off as we emerge from the pandemic (Melchionna, 2022). “In 2022, 38 percent of care was virtual. Researchers expect that in the years to come, telehealth will be optimal not as a replacement to in-person visits but as a complementary service” (Melchionna, 2022, para. 4). This will provide nurses with many future opportunities to contribute to care delivery via telehealth services. Fauteux (2022) called the growth of telehealth the pandemic's silver lining. Let's examine a potential nursing contribution using the Foundation of Knowledge model.

The Foundation of Knowledge Model and Home Telehealth ⬆ ⬇

There is much to learn about usual home telehealthcare service delivery, particularly to the elderly and chronically ill patients. Using the Foundation of Knowledge model is key to learning how to use telehealthcare tools with typical patients (e.g., elderly patients and patients needing pointed care) and to operate effectively as telenurses. To understand the mechanics and effectiveness of home telehealth delivery within the Foundation of Knowledge model, the discussion will begin with a typical home telehealth case, through which the telenurse's role in this model can be explored.

| Case Study: The Role of a Home Telehealth Nurse |

|---|

| Mrs. A. is an 84-year-old woman who was recently discharged from the hospital with a diagnosis that includes an exacerbation of congestive heart failure (CHF). She also has diabetes and hypertension. Mrs. A. was discharged from the hospital on multiple medications and lives alone.

Home care services were initiated with skilled nursing care visits, some home health aide support, and orders to include daily telemonitoring of her vital signs. The telehealth device will remotely monitor Mrs. A.'s blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen saturation, and weight. In addition, the patient will answer customized questions about her disease on a daily basis. This information will then be transmitted daily to the home care agency, where the telenurse can determine appropriate clinical actions based on the data trends and preset baseline alerts that indicate when set parameters have been exceeded.

|

Knowledge Acquisition

As the case study illustrates, knowledge acquisition involves the telenurse receiving information from the telehealth devices via a variety of communication modes. For example, the telenurse receives the patient's vital signs taken in the home and the patient's responses to customized questions. All of this information is transmitted to a remote server or site (i.e., a central station or website) that is easily accessible to the telenurse.

Knowledge Processing

As a result of the telenurse's knowledge acquisition, the next step is knowledge processing (i.e., understanding a set of information and the ways it can be applied to a specific task). In the case study, the telenurse assesses Mrs. A.'s vital signs along with subjective data received from her as a result of the customized questions that she is asked. For example, she might be asked whether she feels shorter of breath on a given day compared to how she normally feels. The telenurse then combines this information with the patient's overall history and diagnosis to get an up-to-date view of the patient's status and considers where this information fits into the clinical picture being presented for this patient.

As an example, the telenurse notes the following: Postacute heart failure patient shows trended data with weight gain of 5 pounds over 2 days, elevated blood pressure, and decreased oxygen saturation and answers yes to questions about increased shortness of breath and increased fatigue. After processing all the current information, the telenurse is able to target the next appropriate steps involving knowledge generation and knowledge dissemination.

Knowledge Generation

By using her own nursing skills and clinical knowledge of the disease process, the telenurse considers all the data as they apply to Mrs. A., decides the best course of action to take, and acts on the data. The telenurse may, in addition, ask a variety of questions to ensure that a complete and accurate decision about the next steps for the patient is made. These questions might include the following:

- Do I need to gather additional data?

- Do I need to call the patient?

- Do I need to call the physician and inquire about a change in the current plan of care?

Knowledge Dissemination

Finally, the telenurse determines how the knowledge will be used and disseminated. Various questions that were posed in the knowledge-generation stage are acted on, including the following possibilities:

- Calling the doctor

- Obtaining a change in medication order

- Calling the patient and instructing her in a medication change

- Reviewing activities that could have led to the changes (e.g., eating salty foods)

- Educating the patient on the disease process, symptom management, and self-management techniques

- Continuing to monitor the patient on an ongoing basis

As the case illustrates, the nurse used various technologies to acquire data; interpreted the meaning of the data, thus generating information and knowledge; and then used that knowledge and wisdom to intervene appropriately.

Nursing Aspects of Telehealth ⬆ ⬇

Understanding telehealth and the potential use of telehealth technology in nursing practice is necessary in today's changing healthcare arena. As this chapter describes, nurses using telehealth have much greater access to their patients' conditions and needs and are able to respond in a timelier way than is possible using only face-to-face visits. Patients' responses to new medications, for example, can be tracked within hours rather than the several days that elapse between face-to-face visits. The telecommunications-ready tools that can be used to achieve these results are described here, and cases that have demonstrated successful outcomes are highlighted.

Telehealth is still a new and evolving technology; while the off-site interventions or contacts often lead to less time being wasted on non-care-oriented tasks because of the efficiencies offered by the technology applications, its use must never be associated with less care. It is also important to note that nursing activity in telehealth still follows the same best practice standards as those espoused in conventional care. One should simply look at the use of telehealth tools as a means for nurses to do their work better.

As the case study demonstrated, a home healthcare nurse working with telehealth tools was able to detect and respond to a patient's condition more expediently than if the nurse had relied solely on scheduled home visits and thus was able to intervene to prevent a potentially serious deterioration in the patient's condition.

History of Telehealth ⬆ ⬇

In the early 1960s, President John F. Kennedy gave the National Aeronautics and Space Administration the goal of landing an American on the moon. A surprise benefit of the space program was the demonstration of effective remote monitoring of the astronauts; thus, modern telehealth was born.

Although most of the advances in telehealth have taken place in the past 30 years, Craig and Patterson (2005) described much earlier examples, such as the use of bonfires to alert neighboring villages of the arrival of bubonic plague during the Middle Ages. Postal services and telegraphs were used to transmit health information in the mid-19th century, and 1910 marked the first transmission of stethoscope sounds over a telephone. Radio communications were used to provide medical support for crews on ships; the Seaman's Church Institute of New York (1920) and the International Radio Medical Center (1938) are two examples of organizations founded to provide health support at a distance. These services were later expanded to cover air travel (Craig & Patterson, 2005). As technology evolved, its use in health care continued to grow. The first reported use of television to monitor patients in a clinical facility occurred in the 1950s, which then led to the development of interactive closed-circuit applications in the mid-1960s. These early applications of television to health care occurred within the facility but still had the benefit of extending the reach of the caregivers because they did not need to be in the same room as their patients to monitor them effectively (Prial & Hoss, 2009).

In the 1970s, uses of more advanced forms of telehealth in the medical field, referred to as telemedicine, included teleradiology and telepathology-radiological and pathological images transmitted to specialists who were located at some distance (Allan, 2006). As additional specialties, such as dermatology and ophthalmology, entered the telemedicine arena, telehealth use enabled even more physicians to access information about their patients, regardless of the distances between themselves and the patients and in sites other than conventional healthcare settings.

Success in telehealth was achieved after decades spent refining the technology, which resulted in clearer imaging, speedier transmissions, and accurate replication of data from remote locations to a central hub. The end results of telehealth interactions today have helped to ensure that professionals, whether working off-site or directly with patients, can replicate the usual clinical interactions in all specialties, regardless of the distance involved in the contact.

The ability to provide better healthcare access is the number one benefit of using telehealth. By reducing the need for face-to-face interaction with the patient, the nurse, physician, or technician can be much more productive. When information is collected in the home, it becomes much more convenient for the patient, and the quality and timeliness of the information are improved dramatically. Home telemonitoring should be viewed as an enhancement to care because it allows more direct, physical intervention to occur only when it is actually needed. Care is not directed by a prescheduled appointment or by subjective perceptions of a condition but instead can be determined by objective measures of physical status. With telehealth, care can also be delivered at the most appropriate site of care, which reduces reliance on emergency departments and inpatient facilities (Prial & Hoss, 2009).

Driving Forces for Telehealth ⬆ ⬇

A significant increase is expected in the use of information technology tools in nursing venues in the coming decades, based on several factors in Western society. The following factors are drivers of the growing trend toward telehealth and technology use and will influence nursing practice significantly in the next decades: demographics; nursing and healthcare worker shortages; chronic diseases and conditions and the pandemic; the new, educated consumers; and excessive costs of healthcare services that are increasing in need and kind.

Demographics

One significant factor is that the baby boomers are getting older and people are living longer. In 2000, 13% of the U.S. population was older than age 65, and the number of older adults continues to grow significantly each day. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (n.d.), every day, 10,000 people turn 65. Consequently, by 2030, 19% of the U.S. population will be 65 years old or older, and the oldest-old (85 years or older) will increase by 3 million persons between 2010 (5.8 million) and 2030 (8.7 million; Vincent & Velcoff, 2010). Also on the rise is the number of older Americans living with at least one chronic disease or condition. The National Council on Aging (2023) reported that nearly 95% of older adults have at least one chronic illness and nearly 80% of the U.S. population over age 65 have two or more chronic illnesses. This trend should alert clinicians to the much greater demand for planned professional care that will arise in the coming years.

| Case Study: Early Detection of a Change in Condition |

|---|

| Mrs. C., an independent 96-year-old woman, has a history of rehospitalization because of atrial fibrillation, which resulted from CHF and hypertension.

After her most recent hospitalization, Mrs. C. was treated and released into home care at an agency in Washington. A home telemonitoring system that tracks and transmits patients' vital signs was placed in her home. The primary goal of placing this patient on the telemonitor was to provide daily monitoring of her condition, thereby avoiding unnecessary rehospitalizations.

One morning, Mrs. C.'s telenurse detected an alarmingly low oxygen saturation level in the patient's transmitted data. In response, the nurse telephoned Mrs. C. and asked her to retake her oxygen reading. The reading was confirmed, and the telenurse contacted the patient's physician, who requested immediate transportation of the patient to the hospital emergency room. Medics were called, and Mrs. C. was taken to the hospital, where she was diagnosed with a pulmonary embolism.

The prompt response resulted from early detection and timely intervention enabled by the home telehealth equipment and a home health nurse's oversight. One notable fact in this case is that although the primary goal of monitoring patients is to avoid unnecessary hospitalization, in this case the hospitalization was necessary for the patient as a result of her elevated blood pressure and compromised oxygen saturation levels. The patient was still asymptomatic at the time of detection. However, the telehealth intervention and subsequent hospitalization allowed for the embolism to be treated before any serious damage had occurred.

Under the traditional home care model, this patient might have been seen by a nurse only two or three times per week, and the clinician would not have knowledge of the patient's condition in between visits. However, having vital patient data tracked and transmitted daily allowed for a rapid response, which resulted in a positive outcome, perhaps a lifesaving intervention for this patient.

|

Nursing and Healthcare Worker Shortages

The crisis related to the well-known nursing shortage has two key aspects: a greater need for nurses by more persons, particularly those living with multiple comorbidities, and a significant decrease in the number of young people entering the nursing profession. Nationwide, the demand for nurses is clearly exceeding the supply. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN, 2022) reported, “The U.S. is projected to experience a shortage of Registered Nurses (RNs) that is expected to intensify as Baby Boomers age and the need for health care grows. Compounding the problem is the fact that nursing schools across the country are struggling to expand capacity to meet the rising demand for care given the national move toward healthcare reform” (para. 1). The AACN projected a 6% increase in the nursing workforce between 2021 and 2031 and a need for 203,200 new RNs per year.

The very serious shortage of healthcare workers in the United States must be addressed with some foresight. Although there is currently more focus on training laypeople, such as aides and other paraprofessionals, to perform certain nursing tasks, this venture certainly cannot replicate the clinical expertise of trained nurses skilled in nursing science. We must begin to look seriously at using effective adjuncts to skilled care, with telehealth being one of these important developments. Some organizations have already begun to do so.

Chronic Diseases and Conditions

Today, chronic conditions are the leading cause of illness, disability, and death in the United States. The number of elderly persons living with chronic disease is estimated at 140 million in the United States and accounts for more than 80% of healthcare expenditures (Dorsey & Topol, 2016). Both chronic conditions and the number of persons with chronic illnesses are expected to increase dramatically in the United States in the next few decades. Many age groups are also affected by chronic disease, not just the elderly. As noted in a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2022), 6 in 10 adults in the United States have a chronic disease, and 4 in 10 have two or more (para. 1). Note that this statistic is referring to adults of any age, when earlier in the demographics section we reported on chronic diseases for the aging population. You can follow the CDC's chronic disease surveillance activities at this website: www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/data/index.htm.

Securing appropriate, adequate, and affordable care services for these populations should be a national concern.

Educated Consumers

The wave of today's aging baby boomers is steering some of the usual health service practices toward a very different course. Many of these individuals are more educated than their parents and more comfortable with the use of technology. They want to become more informed and involved with their care plans. These empowered consumers will be financially motivated with the introduction of consumer-directed healthcare plans that reward healthier lifestyles and better disease management of chronic conditions. All these circumstances will further drive the use and innovation of new technologies to meet consumer need. New plans for this new generation of consumers very much lean toward meeting their demands for when-needed, as-needed care, or care services delivered on their own terms and timing.

Economics

When the drivers of today's healthcare market-the demographics, nursing shortages, and increased number of persons living with chronic conditions and their extensive use of healthcare services-relate to excessive costs of this health care, the critical need for solutions becomes obvious. The CMS (2022) reported that “U.S. health care spending grew 2.7 percent in 2021, reaching $4.3 trillion or $12,914 per person. As a share of the nation's Gross Domestic Product, health spending accounted for 18.3 percent” (para. 2). Much more will be spent annually in the coming decades. Taking all the driving factors of today's healthcare market into account, the question must be asked, What needs to be done to address healthcare issues in the United States to meet the burgeoning numbers and needs of patients?

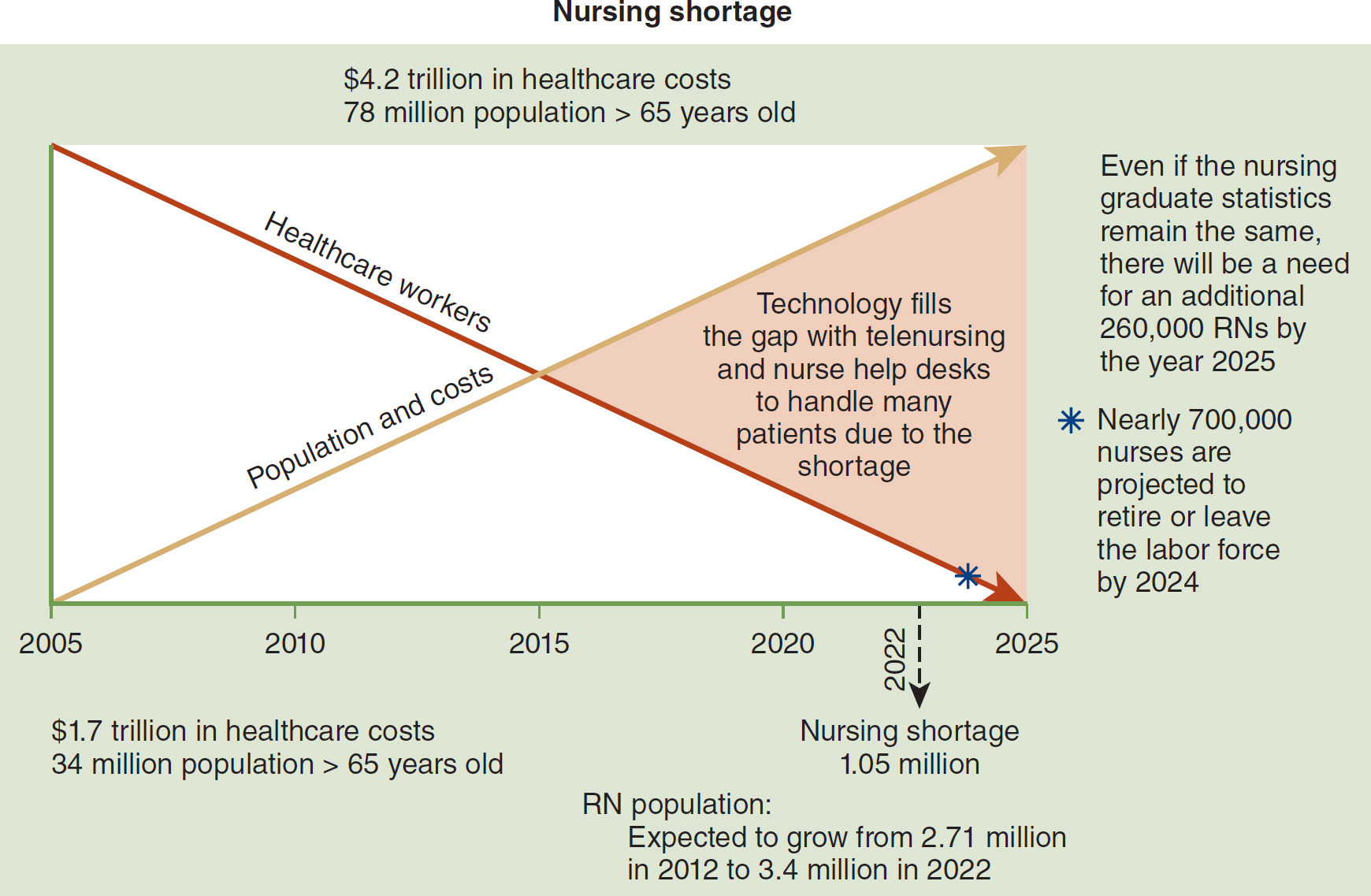

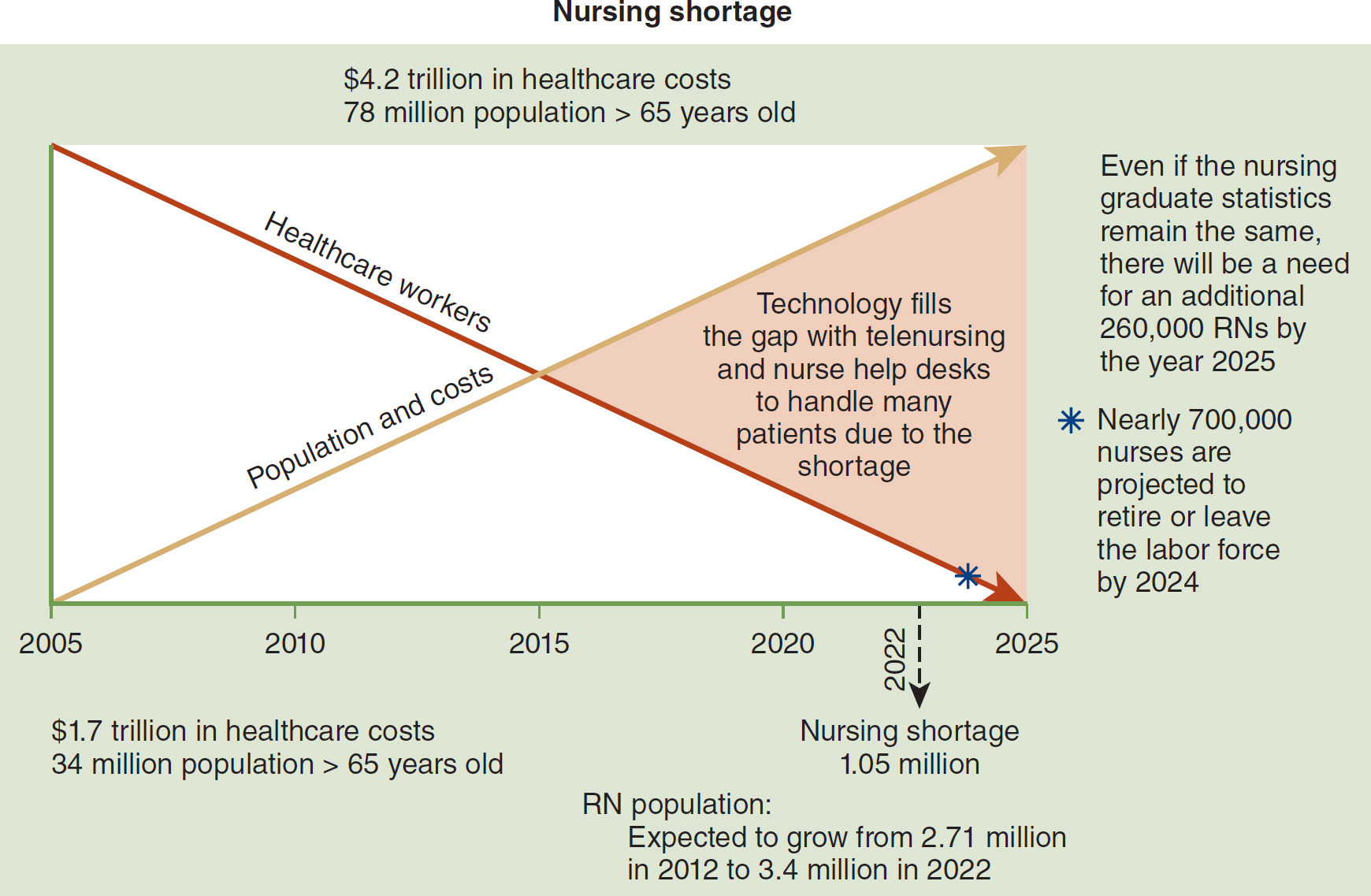

One solution is to develop a new clinical model for U.S. health care that includes technology. Telehealth technology should be included to fill the gap resulting from an overabundance of patients and a scarcity of healthcare providers. This concept is indicated in Figure 18-1.

Figure 18-1 Technology Fills the Gap

A graph depicts the nursing shortage from 2005 to 2025.

The horizontal axis spans from 2005 to 2025 in increments of 5. Two trend lines are plotted. A decreasing trend for healthcare workers and an increasing trend for population costs. Both lines intersect at 2015. The area to the right of the intersection reads, Technology fills the gap with telenursing and nurse help desks to handle many patients due to the shortage. Text alongside the graph reads as follows. 1.7 trillion dollars in healthcare costs; 34 million population greater than 65 years old. 4.2 trillion dollars in healthcare costs; 78 million population greater than 65 years old. R N population: Expected to grow from 2.71 million in 2012 to 3.4 million in 2022. Year 2022: Nursing shortage of 1.05 million. Even if the nursing graduate statistics remain the same, there will be a need for an additional 260,000 R Ns by the year 2025. Nearly 700,000 nurses are projected to retire or leave the labor force by 2024.

Data from Honeywell.

Consider the use of technology that might potentially fill the current gaps in the healthcare system. Tools of telehealth can, for example, help render needed services without requiring in-person professional care at all contacts. The remote, or virtual, visit made by skilled clinicians is just one approach to using the range of health technologies available today. More needs to be learned about what telehealth is, how it works, and which aspects have been successful so that clinicians can plan to incorporate its use into routine clinical care.

Telehealth Care ⬆ ⬇

To begin this discussion, a basic definition of telehealth care is needed. The American Telemedicine Association (ATA, n.d.) provided the following definition:

In brief, telemedicine is the remote delivery of health care services and clinical information using telecommunications technology. This includes a wide array of clinical services using internet, wireless, satellite and telephone media. (para. 1)

The Health Resources and Services Administration (2022) offered this definition: “Telehealth is defined as the use of electronic information and telecommunication technologies to support long-distance clinical health care, patient and professional health-related education, health administration, and public health” (para. 1). Indeed, telehealth is generally used as an umbrella term to describe all the possible variations of healthcare services that use telecommunications. Telehealth can refer to clinical and nonclinical uses of health-related contacts. Delivery of patient education, such as menu planning for patients with diabetes or the transmission of medication reminders, is an example of the health-promoting aspects of telehealth.

Clinical Uses of Telehealth

A few clinical uses for telehealth technologies and sample clinical applications include the following:

- Transmitting images for assessment or diagnosis. One example is transmission of digital images, such as images of wounds for assessment and treatment consults.

- Transmitting clinical data for assessment, diagnosis, or disease management. An example is remote patient monitoring and transmitting patients' objective or subjective clinical data, such as monitoring of vital signs and answers to disease management questions.

- Providing disease prevention and promotion of good health. Examples include case management provided via telephone or smartphone app and patient education provided through asthma and weight management programs conducted in schools.

- Using telephonic or video interactive technologies to provide health advice in emergent cases. An example is performing teletriage in call centers or real-time stroke consultation between a rural health center and an academic medical center.

- Using real-time video. An example is exchanging health services or education live via videoconferences.

Telehealth Transmission Formats and Their Clinical Applications

Nurses must become familiar with the many and varied clinical and nonclinical transmission formats and applications of telehealth technologies so that they can make informed choices about the tools that are available for their use. Among these applications are store-and-forward telehealth, real-time telehealth, remote monitoring, telephony, and mobile health (mHealth). The Center for Connected Health Policy has provided video overviews of the telehealth transmissions and clinical applications. To access these videos, go to www.cchpca.org/resources. Several of the videos posted there reflect telehealth changes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Store-and-Forward Telehealth

In a store-and-forward telehealth transmission, digital images, video, audio, and clinical data are captured and stored on the client's computer or device; then, at a convenient time, the data are transmitted securely (forwarded) to a specialist or clinician at another location, where they are studied by the relevant specialist or clinician. If indicated, the opinion of the specialist or clinician is then transmitted back. Based on the requirements of the participating healthcare entities, this round-trip interaction could take anywhere from a few minutes to 48 hours. In many store-and-forward specialties, such as teleradiology, an immediate response is not critical. Dermatology, radiology, and pathology are common specialties whose practices are conducive to store-and-forward technologies. Transmission of wound care images for assessment by specialty care nurses or other specialists has become a frequently used and important form of home telehealth nursing practice.

Real-Time (or Interactive) Telehealth

In real-time telehealth, a telecommunications link between the involved parties allows a real-time, or live, interaction to take place. Videoconferencing equipment is one of the most common forms of technologies used in synchronous telehealth. In addition, peripheral devices can be attached to computers or to the videoconferencing equipment to facilitate an interactive examination. Use of computers for real-time two-way audio and video streaming between centers over ever-improving and cheaper communication channels is becoming common. These developments have contributed to the lowering of costs in telehealth. See Figure 18-2 for a depiction of this interaction.

Figure 18-2 Physician-to-Physician Consult Using Telehealth

A physician holds a newborn while focusing on two monitors in front of him. One monitor displays a newborn, while the other displays two additional physicians engaged in the consultation.

Reproduced from: Ohio Supercomputer Center. (2008). Governor Strickland, international panel of experts consider establishing telehealth video resource center. www.osc.edu/press/governor_strickland_international_panel_of_experts_consider_establishing_telehealth_video.

Examples of real-time clinical telehealth applications include the following:

- Telemental health, which uses videoconferencing technology to connect a psychiatric nurse with a mental health client.

- Telerehabilitation, which uses video cameras and other technologies to assess patients' progress in home rehabilitation.

- Telehomecare, which uses video technologies to observe, assess, and teach patients living in rural areas.

- Teleconsultations, which use a variety of technologies to enable collaborative exchanges or consultations between individuals or among groups that are involved with a case. These teleconsults may be transmitted live using videoconferencing technology. They may, for instance, involve teaching a certain technique to a less experienced clinician, or they may provide several clinicians with an opportunity to discuss an appropriate approach to a difficult case.

- Telehospice, or telepalliative care, which can use real-time or remote monitoring to provide psychological support to patients and caregivers. Telehealth devices can also play a role in symptom management, in effect helping end-of-life patients achieve an optimal quality of life.

Remote Monitoring (Telemonitoring or Remote Patient Monitoring)

In remote monitoring, devices are used to capture and transmit biometric data. For example, a tele-electroencephalogram device can monitor the electrical activity of a patient's brain and then transmit those data to a specialist assigned to the case. This interaction could occur either in real time or as a stored and then forwarded transmission. Examples of telemonitoring include the following:

- Monitoring patient parameters during home-based nocturnal dialysis

- Cardiac and multiparameter monitoring of remote intensive care units (ICUs)

- Home telehealth-for example, daily home telemonitoring of vital signs by patients and subsequent transmission of those data that enables off-site nurses to track their patients regularly and precisely and address noticeable changes through education and information suggestions about diet or exercise

- Disease management

Telephony

Telephone monitoring (telephony) is the most basic type of telehealth. It can be described as remote care delivery or monitoring in which scheduled patient encounters via the telephone occur between a healthcare provider and a patient or caregiver. Some telephone consultations are automated, with alerts sent to the professional for intervention if a patient issues a negative response to a screening question during an automated call. Bhatia et al. (2022) reported that the majority of their study participants “preferred video over phone-only visits because they felt communication was better and more effective with video” (p. 3489).

mHealth

The use of mobile phones, tablets, and personal digital assistants for managing health is a rapidly advancing form of telehealth. There are numerous applications (apps) that target specific health behaviors and illnesses and that provide a platform for management at a distance. One such management technique is a targeted text message to remind patients to perform a certain behavior, such as monitoring their peak flow to manage asthma or to take medications. Other apps are more specific to public health or provider education. Vo et al. (2019) performed a meta-analysis of qualitative studies published on users' perceptions of mHealth apps. “From the patients' point of view, mHealth could facilitate communication with health care providers and other patients, encourage them to be more participative during clinical encounters, and promote the use of coping techniques to manage their illness” (para. 40). Müeller et al. (2022) collected data on mHealth and digital contact tracing technologies that emerged as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in four countries (United Kingdom, Canada, Kenya, and Rwanda). “It is evident that a wide variety of mHealth and virtual care tools with parallel functionality are being used in different sectors of health care throughout North America, Europe, and Africa” (p. 5). They concluded that “[t]he staggering international increase in the adoption of mHealth and virtual care interventions facilitates researching and comparing their efficacy, paving the way to incorporating them into everyday health care globally” (p. 6).

Nonclinical Uses of Telehealth Technologies

There are also many nonclinical uses of telehealth technologies. Currently, these applications include distance education, including continuing medical and nursing education, grand rounds, and patient education; administrative uses, including meetings among telehealth networks, supervision, and presentations; and research using the internet and other online sources for information and health data management.

All these telecommunications-assisted activities overcome obstacles of distance and provide access to needed health-related information. Clearly, with telehealth, the range of patient care possibilities broadens significantly.

Telenursing ⬆ ⬇

Where does telenursing (nurses using telehealth) fit into today's healthcare delivery arena? As early as 1988, Skiba referred to telenursing as the use of telecommunications and information technology to provide nursing services in health care and to enhance care whenever a physical distance exists between patient and nurse or among any number of nurses. As a clinical field, telenursing is part of telehealth and has many points of contact with other medical and nonmedical applications, such as telediagnosis, teleconsultation, and telemonitoring. Telenurses serve as an integral part of the healthcare delivery team, no matter their location. For example, the National Telenursing Center provides expert consultation and support to remote clinicians as they perform sexual assault forensic examinations and collect and preserve evidence to aid in prosecution of the perpetrator (Mass.gov, n.d.). Read more about this center and the services it provides here: www.mass.gov/info-details/about-the-national-telenursing-center.

Applications of Telenursing in Home Care

Health services or health education and support delivered at a distance to a patient's home using communication devices is defined as home telehealthcare (Kinsella, n.d.). Two key values of telehomecare were also emphasized by Kinsella:

- Nurses can be more alert to patients' current needs and address these needs in a more timely manner than ever before;

- Patients who receive telehealth interventions can receive more comprehensive management, leading to more rapid stabilization and, ideally, learn how to become more competent in self-management skills (learning self-management being the most cost effective home health service interaction of all). (para. 4)

Joo (2022) reiterated that home “telehealth with nurses' care services offers broad access to patients and suggests that it may help reduce health disparities” and that telehealth provides “continuous and person-centered care” (p. 810). Weaknesses of nurse-led telehealth identified by Joo were the lack of evidence-based practice guidelines, physical assessments that were limited by monitoring tools, and difficulties with psychological care.

As telehomecare has evolved, this definition has expanded to include a broader arena of delivery. In fact, the definition of home has expanded to include anywhere outside of an acute inpatient setting-for example, nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and other living situations beyond the single-family home or apartment. Wherever the home setting may be, people want to be cared for there. Today's burgeoning senior population, in particular, has become quite vocal about this preference, and estimates for preferences of aging in place at home are around 90% (AgingInPlace.org, 2023). Fortuitously, the reach of nurses using telecommunications-ready tools in the home is now remarkably extended. Not only have the settings for home care expanded beyond what was usual (the family home) in the past four decades of home health's formal existence, but the types of services delivered to the home have also become more advanced. The home care industry's newest challenge is to work with sicker patients, many of whom have been discharged from hospitals to home earlier than in the past.

This challenge to extend the range of conventional home care is why telehealth can and must be provided to a wide range of patients, including those who

- are immobilized;

- live in remote or difficult-to-reach places;

- have chronic ailments, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, and congestive heart disease; and

- have debilitating diseases, such as neural degenerative diseases (e.g., Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis).

All of these patients may stay at home and be visited and assisted regularly by a nurse via videoconferencing, internet, videophone, or other telecommunications means. These telecommunications-ready tools enable home telenurses to follow through with advanced levels of care as needed.

Still other applications of home telehealth care involve the care of patients in immediate postsurgical situations, those needing care of wounds and ostomies, and handicapped individuals needing physical therapy interventions or telerehabilitation. In addition to this extended range of patients who can be served with telehealth, many more patients can be seen when telehealth is used. For example, in conventional home health care, depending on the distances of travel involved, one nurse may be able to visit as many as seven patients per day. Using telenursing, however, one nurse can remotely visit, or televisit, 12 to 16 patients in the same amount of time using interactive telehealth. Over the past decade, the efficiencies of telenursing have been well documented, as have the resulting improved patient care outcomes that can be expected by frequent telecontact.

Another outpatient application of telenursing is telephony-based call centers, which may be operated by managed care organizations, hospitals, and other health organizations. Some call centers also include telemonitoring services, which allow the patient to stay at home and use different telehealthcare devices to transmit biometric and other medical information back to the call center. Monitoring can be intermittent or continuous. This use of the teletechnology allows clinicians to evaluate patients' status and use the data to make decisions to better manage patients' health conditions.

Many features of call centers' services are comparable to conventional hands-on care in the home. For instance, call centers are typically staffed by RNs who act as case managers or perform patient triage. These professionals can provide information and counseling to patients as part of a disease management program and to educate them on their disease process. In effect, their goal is to offer appropriate access to care (from nurses at the call centers) and help patients to prevent avoidable emergency room visits and rehospitalizations. An example of this assistance includes a nurse calling (i.e., not waiting for a patient to contact the call center) a recently discharged patient with diabetes on a regularly scheduled basis to evaluate progress at home, activity tolerance, medication compliance, foot care, and diet management. This empowering of patients toward self-management is a very significant and needed part of telenursing.

Home care telenursing can also involve other activities, such as providing customized patient education in dietary or exercise needs, nursing teleconsultations, review of results of medical tests and examinations, and assistance to physicians in the implementation of medical treatment protocols. The work can be wide ranging; for example, some home-based telecardiology programs involve the patient, the family, the physician, and a specialized cardiac monitoring center. A multidisciplinary approach is used along with best practice-defined protocols to manage the patient; improve the patient's quality of life; and reduce healthcare costs, especially hospitalization costs. Nurses play a key role in this network of care.

A relatively new role for advanced practice nurses is that of a tele-intensive care unit (tele-ICU) nurse. These nurses provide remote monitoring, oversight, and expert consultation for patients in rural ICUs by examining real-time data collected at the bedside and communicated to a central station. The tele-ICU nurses use computer programs, algorithms, and clinical decision support tools to look for trends indicating that an intervention is needed and then they alert the bedside nurse of the need, thereby providing an extra set of eyes and an advanced level of expertise. Rincon and Henneman (2018) reported that there are over 300 hospitals using tele-ICU services. A typical caseload for a tele-ICU nurse is 30 to 40 patients because (1) the use of high-tech audio and video and other telecommunications tools allows clinicians to move more efficiently between patients; (2) alerts and clinical decision support tools assist with triage and surveillance; and (3) the primary responsibilities of the tele-ICU team are to gather information, monitor for adverse events, and ensure compliance with best practices (p. 42). The tele-ICU market is expected to continue to grow in the coming years because of increased demand and a shortage of intensivists (Fact.MR, 2022).

By reviewing all these examples of telenursing practice, one can see that nurses using telenursing can broaden their involvement in the targeted care of their patients. Some sources have predicted that home care will soon become the hub of much patient activity: The home will be where care that is begun in hospitals and other settings will be managed over the very long term and in the most cost-effective healthcare setting. Home care telenurses can expect to play a vital and dynamic role in the changing delivery systems that are likely to be put in place in the coming decades.

Telehealth Patient Populations1 ⬆ ⬇

Any patient who has a condition that must be monitored is a candidate for home telemonitoring. Patients with chronic illnesses have particularly benefited from ongoing monitoring to prevent acute episodes. Patients who are homebound or who have limited access to transportation are also appropriate candidates for such monitoring. Bhatia et al. (2022) reported that “telemedicine eliminated the time, stress, and cost of commuting and parking at appointments or waiting in clinic rooms and avoided difficulties with stairs or walking distances to reach offices” (p. 3489).

Patients With Chronic Diseases

Given demographics and advances in medical practice, there has been unprecedented growth in the number of patients with chronic diseases. Those patients are at significant risk of having an acute episode when subtle but significant changes in their medical condition occur. The ability to identify these changes in a timely fashion allows for changes in medication, lifestyle, or treatment to occur. Identification of a 3-pound weight gain over 5 days in a patient with CHF, for example, allows for interventions that could prevent an emergency room visit and subsequent hospitalization. The categories of patients with chronic diseases who are most monitored today include those with CHF, COPD, or diabetes and those who require long-term wound care.

These patients, particularly those with higher acuity levels, are at significant risk of having a medical crisis that might necessitate emergency or unplanned acute interventions. Many other patients with chronic diseases are less susceptible to a health crisis but would greatly benefit from home telemonitoring to improve care and reduce costs.

At-Risk Populations

Telemonitoring can be used effectively on patients who are at greater risk for an episode of acute illness. Patients who have a predisposition to disease are at increased risk of medical problems associated with employment, lifestyle, or location, and those patients who have displayed early signs of potentially serious health problems could be placed on preventive monitoring. In such cases, monitoring is used to ensure that interventions are timely and that acute incidents are avoided. Such technology could be part of a healthcare early-warning system and support preventive models of care.

Isolated Patients

Home telemonitoring is effective for patients who cannot physically access healthcare services. The homebound elderly have been among the first to benefit from this technology in conjunction with the home health services they receive. With increasing limits affecting the ability of patients to receive services in the home because of staffing shortages and coverage limitations, telemonitoring technology takes on greater importance in managing homebound patients.

Patients in remote geographic areas have been longtime users of telemedicine interventions. With few rural healthcare facilities being built and access problems becoming more difficult, the use of technology in the home will increase. Even in suburban and rural areas, access is becoming more problematic, requiring greater use of home telemonitoring interventions. A lack of primary care and emergency resources in many urban core areas has prompted many health systems to consider managing certain patients through telemonitoring options and better staging of patient access. Ross (2018) described a home care robot called Rudy:

At the average height of a 10-year-old child, Rudy can also provide light in dark areas, call emergency numbers for help, carry objects, set reminders and notify family members or friends on demand. Rudy can work on its own, or it can be controlled by a nurses' aide or family member from an app. The robot takes the lead and provides care to the older adult, making note of medication usage, response times and more. (para. 6)

Incarcerated Patients

Telehealth services are used extensively in several states to provide mandated medical services for prison populations. Incarcerated patients are considered a vulnerable population and frequently have numerous chronic diseases (e.g., hepatitis C, HIV, COPD, asthma, diabetes, and hypertension) and mental health issues (especially substance abuse) that require continuous care (Young & Badowski, 2017). Correctional telemedicine programs can be cost effective and promote public safety and more humane care by not having to transport prisoners to healthcare facilities for care (UNC School of Medicine, 2021; Weinstein et al., 2014). As Young and Badowski pointed out,

[i]ncarcerated individuals often do not have easy, or any, access to medical professionals with subspecialty training and experience due to the common barriers of geography, limited transportation and cost. . . . For the incarcerated, technology-based solutions must be utilized to improve access to care, connecting patients with providers in a way that removes geographic barriers and the healthcare restrictions of the correctional environment. (pp. 1-2)

Wurzburg (2021) indicated the need for dedicated spaces in prisons for telehealth consultations to ensure patient privacy. Expect that technology-based solutions will increase in the future to provide effective care to this population.

Hospitalized Patients

Home telemonitoring has proved effective in managing the flow of patients into and out of hospitals and other inpatient facilities. Patients are monitored to determine when they are admitted, predict how long they might stay, and prevent unfunded readmissions. Patients undergoing semi-elective procedures can be better staged with scheduling options when they are monitored in the home before admission. If deterioration of the patient's condition is observed, a procedure can be accelerated or planned interventions can be changed.

Monitoring can also be used effectively in length-of-stay reduction strategies. Physicians and surgeons are more confident in discharging patients early when they know that vital signs will be monitored and any decline in condition will be noted in a timely fashion. Use of monitoring effectively allows for an extension of step-down models of care into the patient's home. These length-of-stay management strategies have been particularly useful when hospital beds are in short supply.

Unplanned readmissions are a serious patient care and financial management issue for hospitals. The use of monitoring in the home has consistently reduced unplanned and unfunded readmissions by enabling healthcare providers to obtain reliable information on the patient and intervene appropriately to keep the patient at home.

Emergency Response Situations

Telemedicine will likely be a major component of effective patient management in a major disaster; large-scale nuclear or biochemical attack; and as we have experienced in 2020, the outbreak of a highly infectious disease. In such situations, traditional healthcare delivery systems may become overwhelmed, and patients will need to be more effectively triaged and managed by remote providers. Telemedicine applications allow for a dramatic extension of patient management, triaging options, and off-site providers to be involved in care. If an infectious or communicable disease is involved, patient isolation could be accomplished in the home using telemedicine technology.

Concerned Patients and Families

Perhaps the largest potential market for home telemonitoring is patients and families who want to have reliable and objective information that allows for their involvement in healthcare decision-making. At one extreme is a young person who wants to monitor physiological data as part of a personal wellness or fitness program. At the other extreme are families who want information on the status of a terminally ill loved one in another city. In between, there is a wide range of opportunities for individuals and families to obtain information that promotes realistic and meaningful dialogue with healthcare professionals.

Assisted Living and Subacute Patients

In assisted living facilities or subacute care centers, a kiosk can be used to obtain vital signs for large groups of people. Vital signs reports can then be forwarded on a regularly established schedule to physicians and others involved in the patient's care. This approach allows for better individual care management and lends itself to developing intervention strategies and education options to benefit the entire population of a facility. The CMS issued a telehealth tool kit in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The tool kit detailed the plan for payment for telehealth services and relaxed some of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requirements. Two additional requirements are that the provider must use an interactive video and audio platform that permits real-time communication and that a staff member at the facility must manage the technology during the telemedicine visit (CMS, 2020a). Some facilities have even used access to telemonitoring systems as an inducement to attract potential residents.

Employers and Wellness Programs

Health care is a vital concern for employers. They have a direct financial interest in lowering costs and are financial beneficiaries of long-term-illness preventive strategies. If they can monitor their workers (e.g., offer telehealth options as a wellness program), they will see many benefits for themselves, such as reduced absenteeism and increased productivity. Effective monitoring programs can ultimately lower healthcare costs and associated insurance premiums. Some companies are now exploring the creation of financial incentives for employees who achieve healthcare objectives, such as appropriate weight, reduced blood pressure, and levels of exercise. Monitoring could very well be used as a means of tracking performance in this regard. Friedman (2019) described a comprehensive employee health telemedicine system developed by Tampa General Hospital. The ultraviolet light-sanitized kiosks provide high-definition video and audio visits that allow for general health screening (e.g., height, weight, temperature, pulse, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation) and provide prescription services and self-administered lab kits. “Once the prototype stage for these new kiosks is completed, the hospital says it has plans to deploy them in other venues like airports, colleges, and hotels” (para. 4). The Kaiser Family Foundation (2021) reported that support for telemedicine use by employers increased as a result of the pandemic and that many employers expanded telemedicine coverage for mental health services.

Tools of Home Telehealth

A wide and growing range of telecommunications-ready tools are available for nurses' and patients' use in the home.

Central Stations, Web Servers, and Portals

Central stations, web servers, and portals are various terms for the technologies presently used as part of multifunctional telehealthcare platforms and application servers. These clinical management software programs receive and display patients' vital signs and other information transmitted from a medical device, including blood pressure, weight, and glucose information. Such transmission was initially most accomplished over plain old telephone system (POTS) lines; however, network access and wireless communication are more commonly used as technology advances and access improves.

Central stations and web servers are key components of telehealth that can be as minimal as a single-screen display or as comprehensive as software applications that provide various functions, including triaging the data based on medical alerts, which allows clinicians to quickly identify those patients requiring immediate attention. Other features found in these packages allow clinicians to build personal medical records for patients and provide trended patient data and analysis reports to support improved patient outcomes using telehealth. In addition, some of the software packages provide remote programming capabilities that allow the clinician to remotely program the medical device in the patient's home. Such an application can change monitoring report times for patients, individualize alert parameters, set up reminders, and send educational content to a patient.

Peripheral Biometric (Medical) Devices

Peripheral biometric (medical) devices can consist of fully integrated systems, such as a vital signs monitor, or they may be stand-alone telecommunications-ready devices, such as blood pressure cuffs and blood glucose meters. These devices plug directly into a household telephone jack to send data to a central server location or use Bluetooth technology to transmit data.

An ever-increasing number of peripheral devices are being introduced to the market. Examples of other peripheral devices seen today in home telehealth include pulse oximeters, international normalized ratio meters (measure prothrombin time), spirometers, peak flow meters, electrocardiogram monitors, and card readers and writers that use smart card technology and enable multiple users to use one device.

Rose et al. (2022) assessed the reliability of sensors for assessing gait and chair stand function and concluded that “[w]earable sensors could be used to remotely monitor gait and chair stand function in participant's natural environments at a lower cost, reduced participant and researcher burden, and greater ecological validity overcoming many limitations of lab visits” (p. S19).

Telephones

Telephones are already the most familiar household communications tool used in telehealth care. A telephone device can be augmented with a lighted dial pad, an autodial system, or a louder ringer for easier use by patients who need such augmentation. Telephone systems are still and will continue to be important when there is no internet access in the home.

Video Cameras and Videophones

Video cameras, videophones, and smartphones are readily available consumer items that can be used in telehealth for show-and-tell demonstrations by nurses for patients or to capture wound healing progress, among other applications. Typically, these products operate as a standard telephone or as a video picture telephone, using standard telephone lines to transmit information or interactions. If the patient has a Wi-Fi network, then a smartphone can easily transmit images in this manner.

Currently, the image quality over a POTS is limited by the bandwidth of POTS technology, which favors use of such images for assessment rather than for delivering diagnostic-quality images. These imaging capabilities will improve as integrated services digital network lines become more widely available in the home environment. Typically, medical centers and hospitals have access to larger bandwidth capabilities for image transmission and viewing, thus ensuring high-quality diagnostic images and point-to-point consultations in hospital-based or medical center-based settings.

Personal Emergency Response Systems

Personal emergency response systems are signaling devices worn as a pendant or otherwise made easily accessible to patients to ensure their safety and enable them to quickly access emergency care when needed, usually in case of a fall. A preset telephone number is alerted by the patient pushing a button on the pendant; upon this signal, predesignated emergency help is dispatched. Many newer sensor options for tracking patients at home are being incorporated into multifunctioning personal emergency response system devices, such as alerting a central call center to water flooding or smoke in a patient's home. The next subsection provides details on these sensors and monitors.

Sensor and Activity-Monitoring Systems

Sensor and activity-monitoring systems can track activities of daily living of seniors and other at-risk individuals in their place of residence. These sensors and monitoring systems can provide insight into behavior changes that might signal changes or deterioration of health status. Such technologies consist of wireless motion sensors that are strategically placed around the residence and can detect motion on a 24-hour basis.

Data from these sensors are wirelessly sent to a receiver and base station, which periodically transmit the information to a centralized server. Sophisticated algorithms analyze and compile data on each individual's normal patterns of behavior, including bathroom usage; sleep disturbance; meal preparation; medication interaction; and general levels of activity, including fall detection. Deviations from these norms can be important warning signs of emerging health problems, and the alerts provided can enable caregivers to intervene early (Breaux, 2023).

In addition to widely used fire, security, and home gas detectors, other sensors can monitor appliances to detect whether a household appliance is turned on or off and, with some devices, actually switch the appliance on and off for the resident. Typical applications for affixing programmable sensors can include lamps, television sets, irons, and kitchen stoves. Such sensors might be very valuable for ensuring the safety of elderly, forgetful persons who live alone. One excellent example of today's sensor use for assistance with the elderly are sensors placed in or on stovetops to alert users when they are standing too close to the equipment or the kettle or pot has boiled over. Benefits realized from these technologies include enabling people to live independently with an improved quality of life. They can also provide peace of mind for other family members living at a distance. Smart home technologies have continued to evolve and become more sophisticated and reliable (Hipp, 2023; Matte, 2018), thus providing benefits, such as safety and security, and supporting independent living and providing peace of mind.

Medication Management Devices

Medication management devices address a well-recognized major problem in health care, medication management and compliance. The failure of patients to take medications as prescribed has become a national problem in health care today. This noncompliance can have devastating consequences, particularly for those patients living with chronic illnesses. Lloyd et al. (2019) reported that medication nonadherence ranged from 23% for heart failure to as high as 38% for managing hyperlipidemia. Annual costs of nonadherence, ranging in the billions of dollars, are based on emergency department visits and inpatient hospitalizations as a result of poor disease management.

To address some of these very pressing problems, a host of telecommunications-ready medication devices have become available, and many more are in development. Devices are as simple as a watch that reminds a person to take medications and pill organizers with audible reminders, and some can even be programmed to dispense prefilled containers with medications and alert a patient or caregiver of a missed dose. Furthermore, some of these medication tools send data from the device back to a central server so that patients' medication compliance can be tracked. These telecommunications-ready devices can organize, manage, dispense, or remind, and they will play an increasingly important role in helping people live independently and manage their disease processes through medication compliance. For more information on these devices, see Chapter 15, Informatics Tools to Promote Patient Safety, Quality Outcomes, and Interdisciplinary Collaboration.

Special Needs Telecommunications-Ready Devices

Special needs telecommunications-ready devices can include preprogrammed, multifunctional infusion pumps for meeting a range of infusion needs, including medications for pain management and other infusion delivery needs, such as hydration and nutrition, peak flow meters, and electrocardiogram monitors. Many such tools are in development to meet the more demanding and challenging needs of today's at-home patients. The common goal of these tools is to increase communications between nurse and patient and to increase the nurse's knowledge of the patient's status in a timely manner. A relatively new device approved for home use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is Tyto, described by McDaniel et al. (2019) as follows:

The Tyto device (TytoCare Ltd., Israel) is a novel examination system that includes a built-in examination camera, an infrared thermometer, a wireless communication unit, a lithium ion battery, and a touch screen. The system also incorporates a digital stethoscope, a digital otoscope, and a tongue depressor. The Tyto platform enables the capacity for live video or store and forward applications, and users can be directed by voice or on-screen instructions to obtain images and sounds to comport with the standard of care by enabling a remote physical examination. (p. 2)

Read more about this device and see illustrations provided on the product's web page at www.tytocare.com.

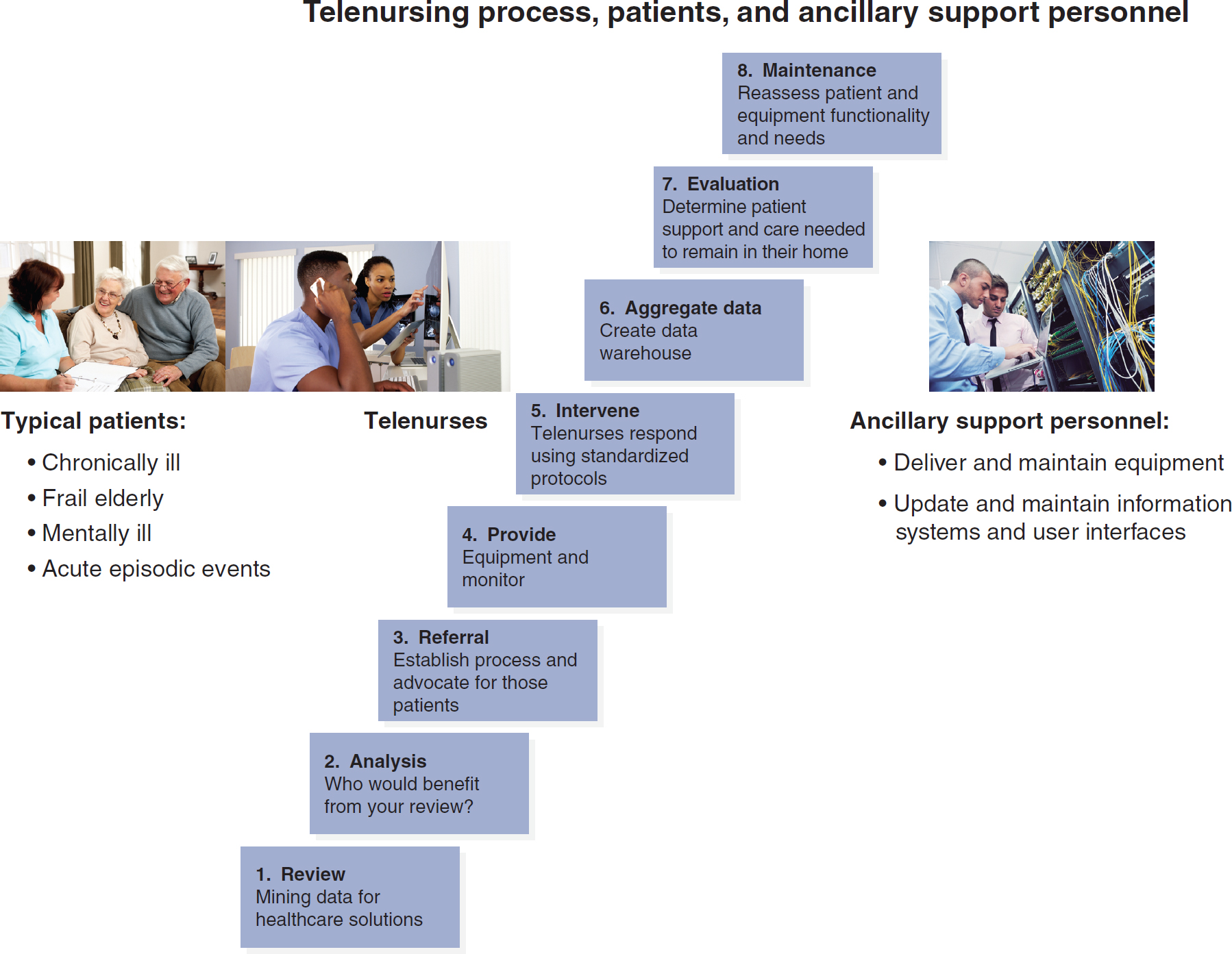

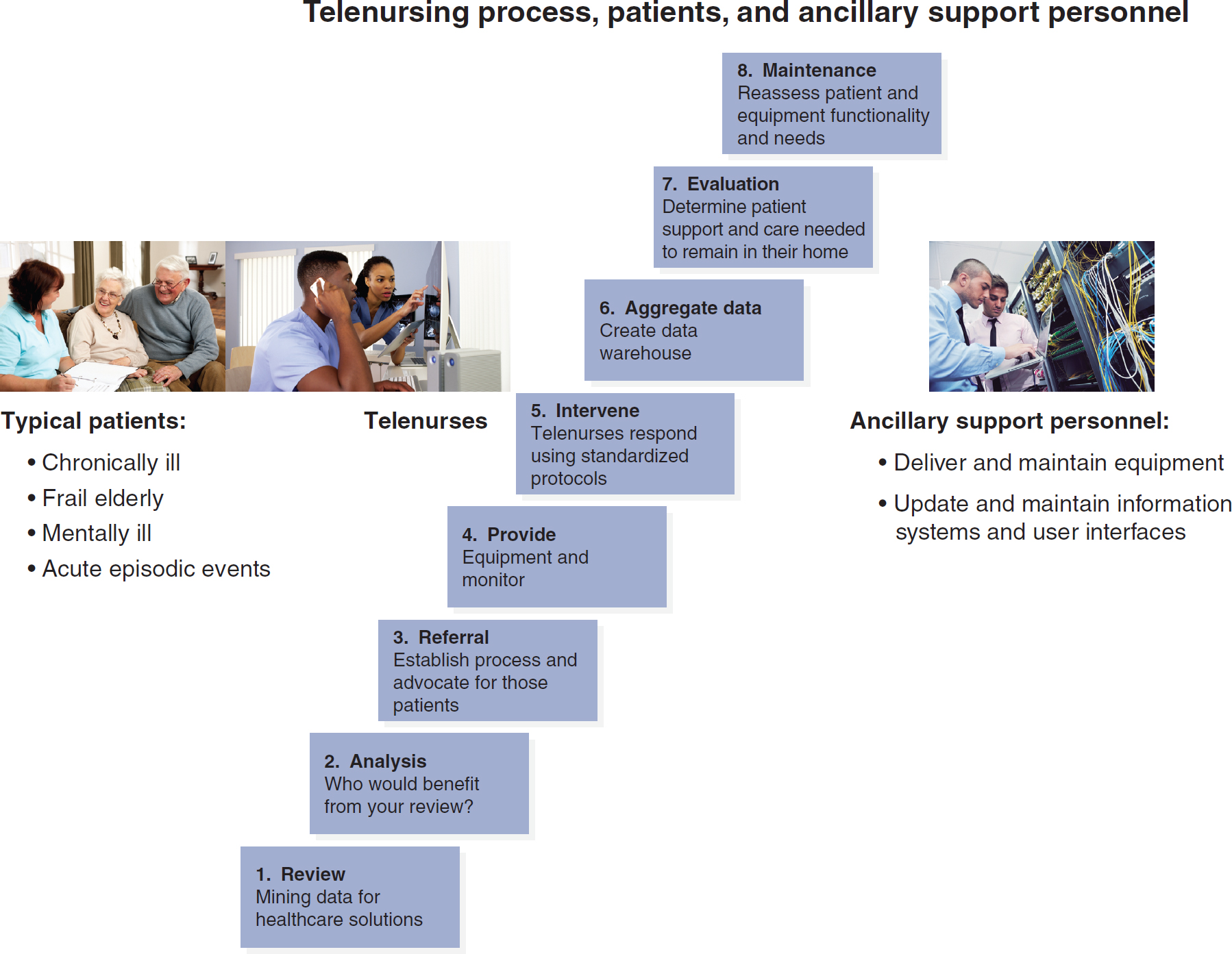

Figure 18-3 illustrates the process for managing home telehealth.

Figure 18-3 Managing Home Telehealth

A flow diagram and three photos depict the telenursing process involving patients and ancillary support personnel.

The flow diagram includes the following path. 1. Review: Mining data for healthcare solution. 2. Analysis: Who would benefit from your review. 3. Referral: Establish process and advocate for those patients. 4. Provide: Equipment and monitor. 5. Intervene: Telenurses respond using standardized protocols. 6. Aggregate data: Create data warehouse. 7. Evaluation: Determine patient support and care needed to remain in their home. 8. Maintenance: Reassess patient and equipment functionality and needs. The three photos feature the following. 1. A healthcare professional interacts with an elderly couple. Accompanying text reads, Typical patients: Chronically ill, Frail elderly, Mentally ill, and Acute episodic events. 2. Telenurses: Two nurses interact with a healthcare professional through a computer. 3. Two healthcare professionals have an interaction in a computer server room. Accompanying text reads, Ancillary support personnel: Deliver and maintain equipment; Update and maintain information systems and user interfaces.

Elderly patients at a consultation: © Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock; telenurses looking at computer screen: © Rocketclips, Inc./Shutterstock; computer technicians: © dotshock/Shutterstock.

1 This section is adapted from Prial and Hoss (2009).

Home Telehealth Software2 ⬆ ⬇

As important as the gathering of data is the organizing of information to support decision-making by clinical professionals. The telehealth software that supports home telehealth programs has become much more sophisticated in recent years and now allows for greater numbers of patients to be better managed by a single clinician. Areas of significant improvement in software include trending, triage, communications protocols, access, and sharing.

Trending

One of the key advantages of home telemonitoring is the creation of a digital health record that allows information to be recorded over time. If patients take their weight and blood pressure daily, most software will graphically display these data over time so that subtle trends can be observed. This type of trend data is much more useful in identifying emerging or developing conditions than is snapshot data, which are collected every 6 to 8 weeks at a physician's office. Trend information can also be developed for groups of patients or populations, which allows for population-based analyses of interventions. For example, one might gather trend information on patients with COPD, patients of a particular physician, or all patients receiving a certain medication.

Triage

Most home telemonitoring systems set an acceptable range of values for individual patients when they are enrolled in the monitoring program. For example, if oxygen saturation, blood pressure, or weight values go above or below predetermined amounts, then the software alerts the appropriate party. More sophisticated software looks at readings from multiple pieces of equipment on a single patient and can give higher priority to patients at risk of an acute episode. These systems help clinicians better organize their work and arrange for appropriate interventions.

Communications

Advanced telemonitoring software utilizes sophisticated electronic notification protocols. Often, when information will be communicated and to whom it is sent are predetermined. Sophisticated protocols can be developed related to both routine and alert information, thereby more effectively organizing communications with physicians, nurses, and caregivers. Some systems also have the capacity to communicate back to the patient or seek additional information under predetermined circumstances.

Data Access and Information Sharing

Many telemonitoring systems house information in web-based formats. This format allows for easy access to the data from any location that has access to the internet. Multiple parties can simultaneously share and view data. Data can also be conveniently transmitted to other clinicians and are updated almost immediately when new values are received. Web-based records are fully HIPAA compliant when appropriate protections and controls are in place.

2 This section is adapted from Prial and Hoss (2009).

Home Telehealth Practice and Protocols ⬆ ⬇

The tools of telehealth described previously are devices that enable remote care delivery, enhance patient care, and improve outcomes. It is important to note that the data received from these tools are useless without some type of clinical oversight. Such tools do not replace the nurse but rather give the nurse the ability to make more informed clinical decisions based on reliable data and a comprehensive picture of the patient's status. In home care, they also direct the clinical resources to patients based on need. The resulting patient-centered approach to care delivers improved patient outcomes and clinical efficiencies.

Home telehealth is indeed a practice, albeit one that represents a change in the current clinical model of practice for home care. Use of the telehealth tools is integrated into the practice to improve patient outcomes. As with any tool, however, the effectiveness is directly proportional to the appropriateness of the tool's application and use. Home telehealth programs differ depending on the type of technology used and the foci of the telehealth programs. However, every program should have telehealth use criteria established, including provisions for informed consent and assessment of the appropriateness of telehealth use for specific situations. The ATA regularly develops and issues practice guidelines, which can be accessed at its website: www.americantelemed.org/resource_categories/practice-guidelines. Note that the ATA requires you to register with them to access the guidelines.

Other professional organizations, such as the American Nurses Association (ANA), the AACN, and the American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing (AAACN), also provide telehealth practice guidelines. Patient criteria for telehealth should be governed by established inclusion and exclusion guidelines that detail who is eligible and appropriate for each type of technology. Other criteria include establishing policies and procedures that address patient enrollment, education, and equipment setup; patient and caregiver and home assessment; patient informed consent; and privacy and confidentiality rights. In addition, a clinical plan of care that is specific to patient needs should be developed. Telehealth pathways and protocols ensure more focused work with patients and allow for targeted interventions.

| Case Study: Home Telemonitoring of Multiple Illnesses |

|---|

| The patient is a 71-year-old male who has stage 4 cardiomyopathy/pulmonary hypertension, atrial fibrillation, COPD, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. He has been an active patient with a home healthcare agency for several years, with an admitting diagnosis of CHF.

Initially, the patient was seen three times a week by an RN for CHF assessment and management. The patient's history included frequent hospitalizations for exacerbation of CHF and uncontrolled atrial fibrillation. He experienced a total of four hospitalizations in the year before placement of a telemonitoring system in his home, after about 6 months of receiving conventional home care.

Ever since the patient was placed on a telemonitoring system for daily tracking more than 8 months ago, he has not been hospitalized. The telemonitoring interactions with his nurse have made him very conscious of the role that his medications, diet, and fluid restrictions play in his overall health status.

In addition, the telemonitor has proved its benefits to local physicians. The patient's family physician, cardiologist, and pulmonologist were able to provide better care for the patient by examining the tabular and graphical trends that were elicited from the daily vital signs monitor. This information aided in the titration and addition of the various medications needed to control the patient's CHF and atrial fibrillation. The physicians were able to ascertain the response to the medication adjustments and other treatment modalities, such as oxygen titration. At the start of care, the patient's weight was 196 pounds; it is now at a stable 187 pounds, with the symptoms more controlled than they have ever been.

The patient's nurses, meanwhile, have peace of mind knowing they can keep an eye on their patient daily while making additional visits as needed, with the documentation being provided by the system to justify the additional nursing visit. This tool can also be incorporated into the nurses' care plan, enabling a higher standard of care to the patient.

At present, the patient is being case managed by nursing staff visits that occur once per month. He now enjoys a newfound peace of mind and security and an improved state of health, something this patient had not experienced in more than a year.

|

Clearly, by using a protocol for patients who regularly use telehealth equipment for tracking their status, nurses receive a good deal more targeted information than can possibly be obtained during scheduled in-person visits. As a result, the use of telehealth tools, together with clinical oversight and practice, makes possible more efficient and effective clinical management by allowing the patient's needs to drive the care. As home telehealth protocols are used more extensively, the improved clinical and operational efficiencies may ultimately affect the home care agency's bottom line.

It is important that this clinically driven, as-needed approach to care services is not misunderstood as providing less care. In the previous case study, a proactive, patient-centered approach enabled a home healthcare agency to identify early exacerbations in a patient's condition and take appropriate action.

Legal, Ethical, and Regulatory Issues ⬆ ⬇

Telehealth is affected by certain legal, ethical, and regulatory issues of which nurses should be aware. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, interstate practice of telenursing, for example, required nurses to be licensed to practice in all the states in which they provided telehealth services and directly interacted with patients. This was particularly important when nurses worked for health systems that are located near state borders and draw patients from both states. A possible solution is the development of the federally sponsored physician Interstate Medical Licensure Compact and Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC) to facilitate portability of licensure across state lines. However, this federal initiative has met opposition from some states that are unwilling to share licensing authority. Gaines (2023) reported that the original NLC was updated in 2018 to the Enhanced Nursing Licensure Compact (eNLC). The eNLC requires criminal background checks and fingerprinting. Currently, 40 states have enacted eNLC licensure, and 4 states have legislation pending. Follow these developments at your state licensing boards. The Center for Connected Health Policy provides an interactive map of current and pending state laws and reimbursement policies at www.cchpca.org/telehealth-policy/current-state-laws-and-reimbursement-policies.

Some evidence exists that these regulations are slowly changing, so it is important for all licensed professionals to be aware of legislation governing specifically their practice. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, some laws and regulations related to telehealth practice were temporarily suspended. Telehealth laws and regulations are likely to change again as a result of the end of the public health emergency declaration. Shachar et al. (2020) indicated that “[t]o maintain the impetus for change and the momentum for telehealth services that have resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic, the US cannot revert to prepandemic telehealth regulations. Neither can the US simply adopt the recent changes, because they lack nuance to support clinicians while ensuring safety and privacy for patients: a third regulatory path is needed” (p. 2376). Follow these developments at the official U.S. government website: https://telehealth.hhs.gov/licensure/getting-started-licensure.

Patient confidentiality and the privacy and safety of clinical data must be given special consideration. Informed consent releases to receive telehealth services are a critical first step and recommended by the Center for Connected Health Policy (n.d.). A typical informed consent for telehealth is a written document that describes what the patient can expect and the security measures that are in place to protect privacy. Informed consent policies for telehealth may vary by state (Center for Connected Health Policy, n.d.). You will also find important informed consent information at https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/preparing-patients-for-telehealth/obtaining-informed-consent. Pointed efforts must be continually undertaken by the nurses' agencies to upgrade their information systems to ensure that a high level of data security is provided at all times. Telehealth providers must adhere to all data privacy and confidentiality guidelines and remain vigilant to ensure that all involved parties, including the technical staff support assistants, have appropriate training in privacy and confidentiality issues.

The Patient's Role in Telehealth ⬆ ⬇