Objectives ⬇

- Describe nursing research in relation to the Foundation of Knowledge model.

- Explore the acquisition of previous knowledge through internet and library holdings.

- Explore information fair use and copyright restrictions.

- Assess informatics tools for collecting data and storing information.

- Compare tools for processing and analyzing quantitative and qualitative data.

Key Terms ⬆ ⬇

Introduction: Nursing Research and the Foundation of Knowledge Model ⬆ ⬇

The Foundation of Knowledge model suggests that the most important aspect of information discovery, retrieval, and delivery is the ability to acquire, process, generate, and disseminate knowledge in ways that help those managing the knowledge reevaluate and rethink the way they understand and use what they know and have learned. These goals closely reflect the Information Literacy Competency Standards for Nursing, published by the American Library Association (ALA) in 2013. These standards were derived from the Information Literacy Standards for Higher Education (Association of College and Research Libraries [ACRL], 2000). Specific standards for nursing were developed because nursing excellence depends on the judicious use of the best evidence and is informed by translational research.

According to the ALA (2013), an information-literate nurse is able to do the following:

- Determine the nature and extent of the information needed

- Access the needed information effectively and efficiently

- Critically evaluate information and its sources and determine the need for further information

- Use information effectively to accomplish a specific purpose, either individually or as a group member

- Understand the economic, legal, and social issues surrounding the use of information and access and use information ethically and legally

In addition, new challenges arise for individuals seeking to understand and evaluate information because information is available through multiple forms of media (i.e., graphical, aural, and textual). The sheer quantity of information does not by itself create a more informed citizenry without complementary abilities to use this information effectively. More significantly, information literacy forms the basis for lifelong learning, a commitment that is required for a professional to maintain competency and navigate ever-changing approaches to care.

| Case Study |

|---|

| During rounds, Charles encounters a rare condition he has never personally seen and only vaguely remembers hearing about in nursing school. He takes a few moments to prepare himself by searching the internet for information. That evening, he does even more research so that he can assess and treat the patient safely. He searches clinical databases online and his own school textbooks. Most of the information seems consistent, yet some factors vary. Charles wants to provide the highest quality of patient care and safety. He wonders which resources are the most trusted and which are the most accurate. |

Knowledge Generation Through Nursing Research ⬆ ⬇

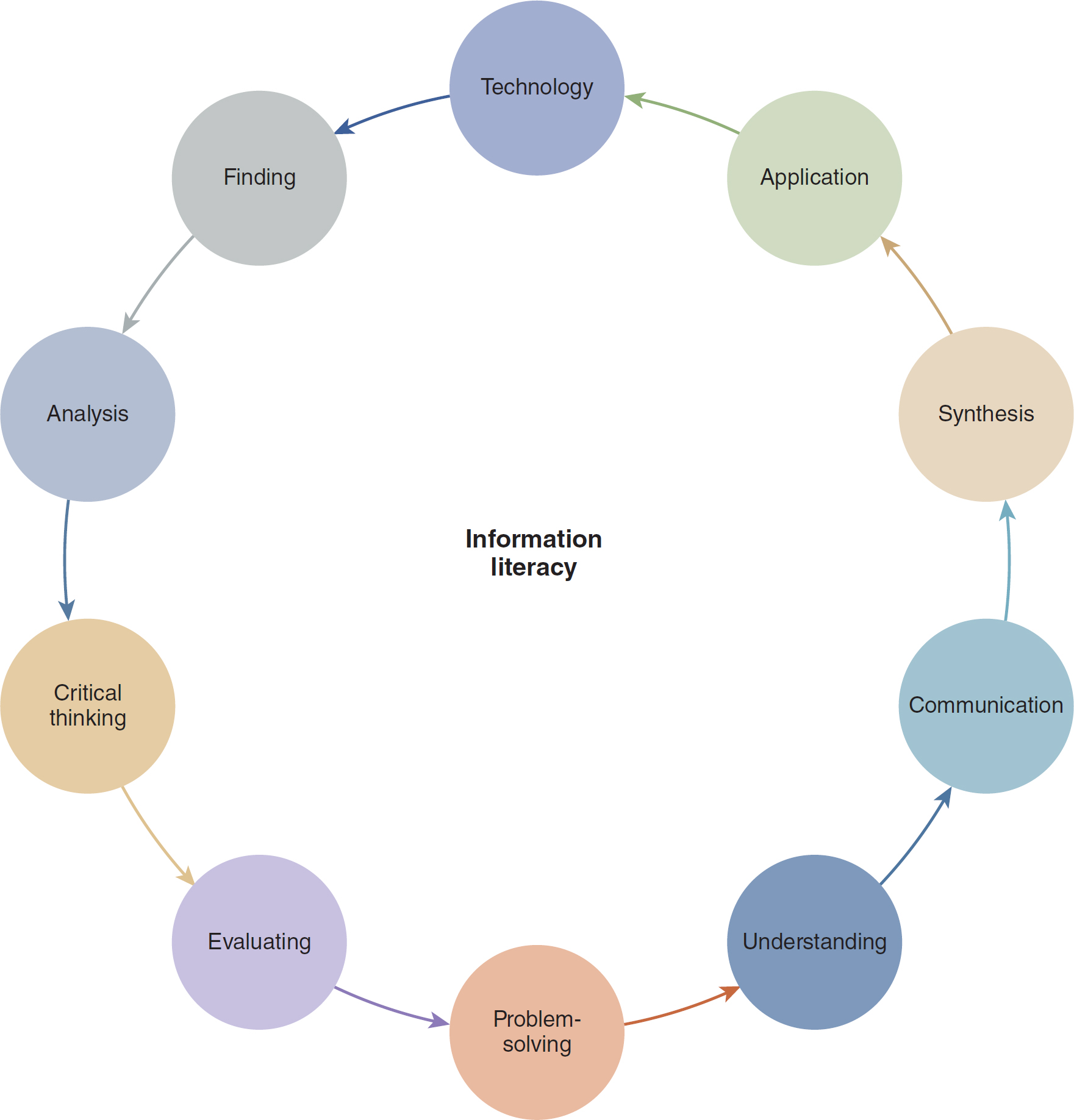

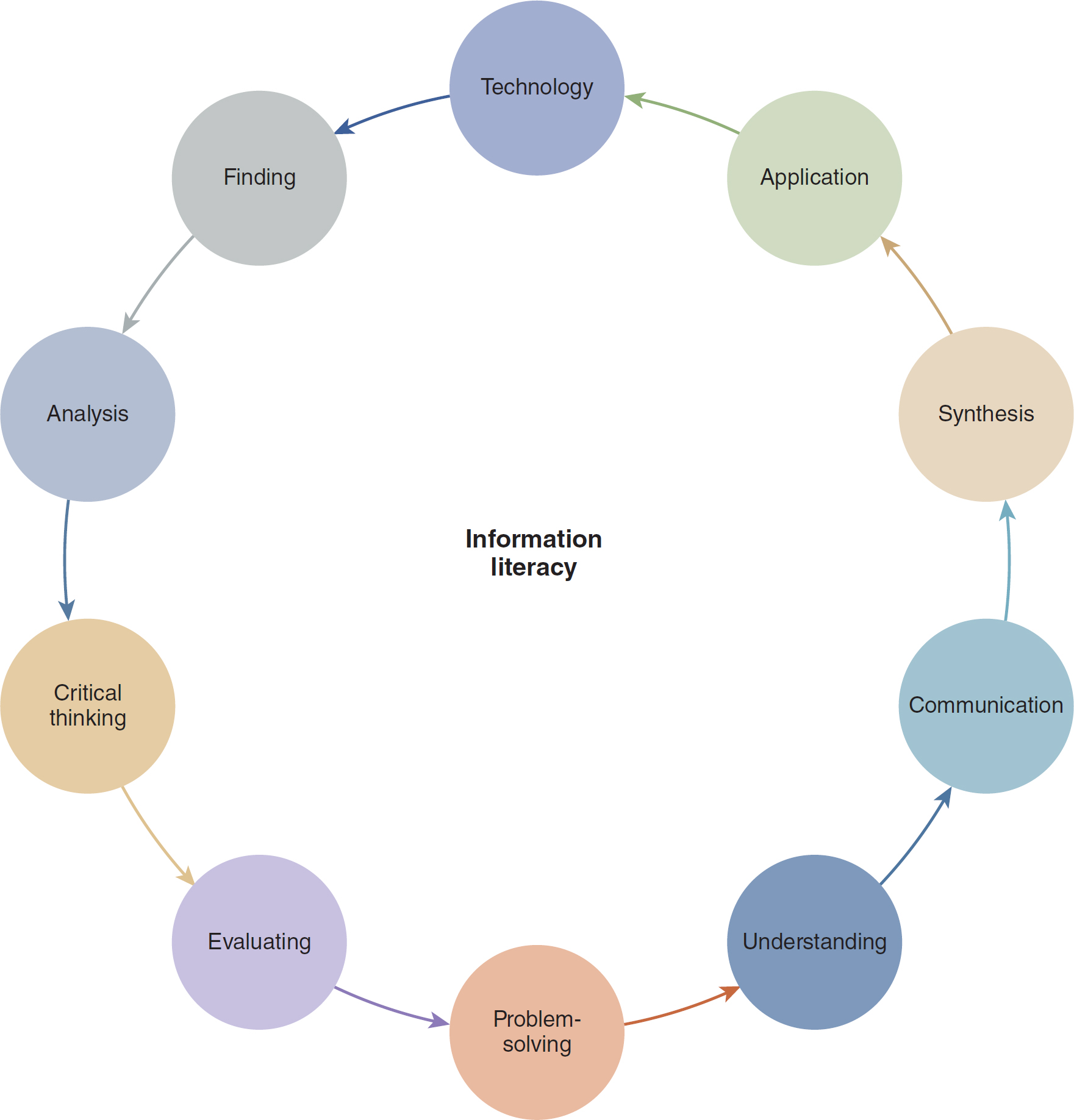

Information literacy is an intellectual framework for finding, understanding, evaluating, and using information (Figure 21-1). These activities are accomplished in part through fluency with information technology and sound investigative methods but, more importantly, through critical reasoning and discernment.

Figure 21-1 Information Literacy

The components of information literacy encompass technology, application, synthesis, communication, understanding, problem-solving, evaluating, critical thinking, analysis, and finding.

Because nursing informatics (NI) combines all four nursing practice areas (i.e., clinical, research, administration, and education), the ability to recognize the need for a specific kind of information and then locate, evaluate, and effectively use that information is paramount. It is important that nurse educators prepare nursing students for information-literate practice in technology-laden healthcare environments. Stephens-Lee et al. (2013) stressed that “[n]ursing students require opportunities to help them develop NI skills and abilities to prepare them for contemporary workplaces” (para. 39). Nash (2014) stated that

[i]f we desire nurses who practice the art of nursing as well as the science of nursing, we must make it a priority to address the issue of integrating those interpersonal and critical thinking skills we value into an increasingly complex, high-tech, fast-paced healthcare system that often works against us practicing at our very best. (p. 13)

Nursing students today use technology in their personal lives, and they know that

technology allows them to share photos (Flickr), exchange files and images, send videos (YouTube, Snapchat), bookmark (Quorum or Diigo, Pinterest), micro-blogs or short postings (Twitter, Tumblr, MySpace), blog (Blogger), socialize (Facebook, Vimeo, Instagram), search (Google, Google+), and network professionally (Altogether, LinkedIn, Yahoo Groups). (Merrill, 2015, p. 72)

Nursing faculties must be able to adapt their teaching in this new technology era so that they engage their students and help them assimilate technology as they prepare for their professional nursing roles. Focusing on nurses' providing direct patient care, Piscotty et al. (2015) stated that “finding methods that can help nurses offer safe and effective care using technology is an absolute necessity” (p. 287). As nurses enact their roles as administrators, researchers, educators, and clinical staff members, integrating technology into the current technology-laden information era is paramount.

We must also support the evolution of nursing and assist nurses and nursing students in their quest for knowledge to improve patient care and patient outcomes. They must be encouraged to question how they practice and why they do what they do, recognize the information needs necessary to enact change, and search the literature for evidence. Once they locate appropriate literature, they must be able to judiciously examine and analyze the findings. Following their analysis, they must synthesize, apply, and implement what they have learned from the literature to what they experience in their practice. If they deem a change in practice is warranted, the change should be instituted and its efficacy evaluated. For this process to work, nurses and nursing students must know how to access the literature, search for appropriate resources, and evaluate specific findings.

Acquiring Previously Gained Knowledge Through Internet and Library Holdings ⬆ ⬇

In an environment characterized by rapid technological change coupled with an overwhelming proliferation of information sources, nurses face an enormous number of options when choosing how and from where to acquire information for their academic studies, clinical situations, and research. Because information is available through so many venues-libraries, special interest organizations, media, community resources, and the internet-in increasingly unfiltered formats, healthcare practitioners must inevitably question the authenticity, validity, and reliability of information (ACRL, 2016).

Often, the retrieval of reliable research and information may seem to be a daunting task in light of the seemingly ubiquitous amount of information found on the web. Focusing on specific information venues not only aids this search but also assists in negotiating the endless maze of resources, which allows a nursing practitioner to find the best and most accurate information efficiently.

Professional Online Databases

Professional databases represent a source of online information that is generally invisible to all internet users except those with professional or academic affiliations, such as faculty, staff, and students. These databases, which range from specific to general, act as collection points by aggregating information, such as abstracts and articles from many journals. Two such databases include the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and MEDLINE. CINAHL, for example, specifically includes information from all aspects of allied health, nursing, alternative medicine, and community medicine. The MEDLINE database contains references to more than 22 million journal articles and is maintained and produced by the National Library of Medicine. PubMed comprises more than 30 million citations for biomedical literature from MEDLINE, life science journals, and online books. The Cochrane Library is a collection of databases in medicine and other healthcare specialties; its core is the collection of Cochrane Reviews, which is a database of systematic reviews and meta-analyses that summarize and interpret the results of medical research. Other databases such as PsycInfo; PsycArticles, which is a database of articles from journals published by the American Psychological Association (APA); and the Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC) database may also benefit nursing. Many databases also offer full-text capabilities, meaning that entire articles are available online. The articles and abstracts contained within these databases have already withstood the rigors of publication in professional journals and therefore are considered viable and authentic peer-reviewed sources.

Libraries with subscriptions to databases often employ library professionals who are able to help patrons sift through the vast amounts of available electronic information; using the expert research capabilities of a health science librarian at one's local university is the best way to learn how to conduct database searches that yield the most efficient and useful results. Also useful are websites that provide tutorials on best searching practices specifically for medically oriented databases, such as the tutorials provided by EBSCO (an acronym for the Elton B. Stephens Company) to support searching the CINAHL database.

Search Engines

Search engines allow users to surf the web and find information on nearly anything, although many researchers steer clear of search engines because of the vast amounts of unsubstantiated information they are likely to uncover. Because no legitimacy needs to be provided for any information that appears on the web, an author can make claims, substantiated or not, and still use the web as a publishing venue. Despite the pitfalls associated with search engines in general, they can yield a bounty of useful information when used with discretion.

Each search engine will produce results different from those produced by other search engines when used for the same research. For example, one popular search engine ranks its results by the number of hits that a page or site has received. Whereas the most popular research results are likely to be relevant, the order in which results appear does not indicate quality or viability of the source.

Web address (i.e., domain) suffixes (e.g., .com, .edu, .org, and .gov) indicate who is responsible for creating the website. Although a .edu site is hosted by an educational institution and for that reason may seem legitimate, consider that it could also belong to a student stating personal opinion, gossip, or guesswork. In contrast, .gov sites are maintained by the government and nearly always have professional contact information. Web hosts develop new domain suffixes constantly; therefore, although looking at the suffix can be useful, it should not be the sole deciding factor when choosing to trust information.

Information found on a web page should never be blindly trusted. When possible, check the date of the most recent update (How old is the page?), contact information (Is a bibliography or list of sources provided?), links to external sources (Do they seem relevant?), and previous attained knowledge from other reputable sources (Is the information too unbelievable?).

Fees and information retrieval charges should be approached with skepticism. Private companies do offer information aggregation services for a fee. In these cases, users pay a flat monthly fee for access to collections of articles in a particular field. What users (especially those affiliated with an academic institution) may not realize is that they are likely to have free access to the same, if not more complete, information through their institution's library system. Be sure to check with the medical librarian in a hospital system as well as the academic librarian in an educational institution.

Some legitimate databases and traditional newspapers that maintain a web presence do provide access for a small fee, but just as many other providers simply ask users to register to see articles for free. Many nursing students and professionals affiliated with a university may find that their university library has already purchased access for the student body.

Electronic Library Catalogs

Nearly all higher education institutions have placed their library catalogs online. Although this is an obvious convenience for many students, some nursing professionals not used to working completely online may be intimidated by an e-catalog. Library professionals at the tiniest university and the busiest community college are available to demonstrate how to navigate a basic search of their library's catalog. Asking for assistance in learning how to access the vast assortment of journals, books, databases, and other resources available at one's college library is an excellent idea. Students in nursing programs at larger universities will likely find free classes that specifically teach users how to navigate and use the online catalog. If smaller colleges and universities do not offer these services, one should take advantage of the library's online tutorials, help pages, frequently asked questions pages, and online reference service (if available). Local public libraries often have subscriptions to popular databases and offer free classes on searching techniques to patrons, providing yet another free access point to the best information for one's research needs. Making full use of available library resources serves to strengthen information literacy skills, which enables learners to master content and extend their investigations, become more self-directed, and assume greater control over their own learning (ACRL, 2016).

Fair Use of Information and Sharing ⬆ ⬇

Copyright laws in the world of technology are notoriously misunderstood. The same copyright laws that cover physical books, artwork, and other creative material apply in the digital world. Have you ever given a friend a flash drive that contains a computer game or some other type of software that you paid for and registered? Have you ever downloaded a song from the internet without paying for it? Have you ever copied a section of online content from a reference site and used that content as if it were your own? Have you ever copied a picture from the internet without asking permission from the photographer who took the picture? Have you ever copied and pasted information about a disease or drug from a website and then printed out the information to give to a patient or family member? All of these situations are examples of the type of copyright infringements enabled by technology that occur almost without thought.

The value of creative material-whether it is written content, a song, a painting, or some other type of creative work-lies not in the physical medium on which it is stored but rather in the intangibles of creativity, skills, and labor that went into creating that item. The person who created the material should be properly credited and possibly reimbursed for the use of the material. How would musicians be reimbursed for their music if everyone just downloaded their songs illegally from the internet? Imagine that you created a game to teach patients with type 1 diabetes how to manage their diet, and other nurses copied and distributed that game without getting your permission to do so. How would you feel?

Almost all software, music, and movies (either digital or in hard copy [CDs or DVDs] form) come with restrictions on how and why copies can be made. The license included with the software clarifies exactly which restrictions are applicable. The most common type of software license is a shrink wrap license, meaning that as soon as the user removes the shrink wrap from the CD or DVD case, they have agreed to the license restriction. Most computer software developers allow for a backup copy of the software to be made without restriction. If the hard drive on the user's computer fails, the software can usually be reinstalled through this backup copy. Some software companies even allow the purchaser of a software package to transfer it to a new user. In this case, typically, the software must be uninstalled from the original owner's computer before the new owner is free to install the software on their computer. Most of these restrictions depend on the honesty of the user in reading and following the licensing agreement. As a result of widespread abuses, however, the music and film industries commonly include hardware security features in their products that block users from making a working copy of a music CD or movie DVD.

The bottom line is that copyright laws also apply to the digital world, and copyright violations can lead to prosecution. Advances in technology have made the sharing of information easy and extremely fast. A scanner can convert any document to digital form instantly, and that document can then be shared with people anywhere in the world. Nevertheless, the person who originally created that document has the right to approve of the sharing of the work. Carefully read the fine print of any software purchased, and be sure to clarify any questions regarding how that software can be copied. Avoid downloading music illegally from the internet, and do not use information from the internet without permission to do so or without citing the reference appropriately. Healthcare organizations that allow access to the internet from a network computer should ensure that users are well aware of and compliant with all copyright and fair use principles.

Informatics Tools for Collecting Data and Storing Information ⬆ ⬇

As knowledge workers, nurses are already intimately familiar with data collection as they enter patient data in electronic health records (EHRs). As early as 1991, Werley et al. advocated for use of standardized data collection using the Nursing Minimum Data Set. Although these standardized nursing data sets comprise gathered information, such as healthcare definitions, classification systems, and nursing information, they were primarily used to support patient care and not for research.

Nurses have traditionally generated and recorded data from their own observations or with the assistance of various devices. Free text (i.e., informational data, such as drug dosages administered, resources used, and problems diagnosed) is recorded electronically. Free text is then interpreted and organized by some standardizing principle, either manually or by computer. In this way, data (often qualitative data that cannot be traditionally measured in a numeric sense) can be organized and processed. A central issue to the generation and analysis of free-text data is the lack of a generally accepted set of terminology to capture nursing data.

Knowledge networks are rich and dynamic digital collections affording high-quality knowledge support to their users for sharing, developing, and evolving knowledge. Knowledge networks include linked users of research collaborations. The nurses as users of the knowledge network should assess the knowledge base and determine the extent to which the network is generating new knowledge or recycling current knowledge to facilitate new insights.

Database management systems consist of software designed to collect, sort, organize, store, retrieve, select, and aggregate data. Nursing and health data may be classified into four basic types: (1) resource data (e.g., financial information), (2) patient and client demographics, (3) activity data (i.e., clinical data), and (4) health service provider data. These primary data may be either recorded manually or collected electronically, with manual collection providing a greater opportunity for error. The process of electronically recording data follows a programmed set of instructions built into the software, thereby substantially cutting down on collection error. Of paramount importance in the collection process are the data collection form and the computer interface used for inputting the data, both of which affect the completeness, consistency, and accuracy of the resulting data (Brackett, 2015).

Quantitative data collection tools, or instruments, include questionnaires, interviews, surveys, quizzes, assessments, email interviews, and web-based surveys, all of which generate numerical rather than text-based data. Questionnaires-one of the most popular means of data collection-can be administered in hard copy form or programmed into a website where individuals may answer the questions electronically (Statistics Canada, 2016). Other electronic data collection tools include handheld devices and on-site laptops. A key benefit of using electronic data collection is the ability to directly transmit data to another computer for compilation and analysis, thereby cutting down on the risk of error (Kania-Richmond et al., 2016; Teale et al., 2013).

Of course, one must always be cognizant of the need to protect the privacy of participants by de-identifying data collected for research and having tools in place to provide secure transmission and storage of private information. Some researchers are finding rich qualitative data on public and freely available patient support sites and blogs. An important issue associated with such internet-based data collection is whether participants actually are who they say they are and whether they actually have the variable of interest or are just pretending to be someone or something they are not. Remember that the same rules for protecting human subjects apply no matter where the data are accessed or collected, and all research involving human subjects should be formally approved by the appropriate institutional review board (IRB). Many IRBs have specific policies in place that govern electronic data collection and storage to ensure that the rights and privacy of research participants are protected (Penn State Senior Vice President for Research, n.d.).

Harder-to-measure, nonnumerical qualitative data can be collected electronically in the form of a narrative, or diary-like, entry. Much in the way that free text is analyzed and sorted, this narrative dialogue is assessed and then coded to look for patterns and themes that represent the phenomenon under study. For example, a nurse researcher may be interested in studying the lived experiences of women recently diagnosed with breast cancer and therefore may ask them to keep a diary of their thoughts, questions, and treatment experiences.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the commitment to collecting healthcare data in a standardized way to facilitate data sharing and treatment outcomes. As Eddy (2022) described, in response to the pandemic, the National COVID Cohort Collaborative (NC3) was formed, and biomedical researchers opted to use a common data collection model, the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) Common Data Model (CDM). The Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI) (n.d.) organization explains, “The Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) Common Data Model (CDM) is an open community data standard, designed to standardize the structure and content of observational data and to enable efficient analyses that can produce reliable evidence” (para. 1). The ability to easily share standardized healthcare data promotes descriptive analyses, research collaboration, public health surveillance, and predictive modeling (OHDSI, n.d.).

Tools for Processing Data and Data Analysis ⬆ ⬇

Data analysis is the process by which data collected during the course of a study are processed to identify trends and patterns of relationships. Descriptive statistics allow the researcher to organize information meaningfully, thereby facilitating insight by describing what the data show. A range of tools exist to facilitate such analysis, including specialized databases; word processing, spreadsheet, and database applications; and statistical packages (Laitinen et al., 2014).

Quantitative Data Analysis

Quantitative data focus on numbers and frequencies, with the goal of describing a situation or looking for more robust relationships, such as correlations, and specific variable contributions to an outcome. This aim stands in contrast to qualitative analysis, which focuses on experiences and meaning. Although the kind of data generated by quantitative collection is fairly straightforward and easy to analyze (i.e., responses to questionnaires, experiments, and psychometric tests), quantitative data analysis has come under criticism. Psychologists, for example, prefer to use a combination of quantitative and qualitative data and to back up research participants' explanations with statistically reliable information obtained by numerical measurement (Holah.co.uk, n.d.).

In quantitative studies, variables represented by data are collected in numerical form. These values are then entered into specific fields that have predetermined meanings or are coded. Various quantitative data analyses can be applied to nursing research, such as intervention research, quality improvement studies, and outcomes research. One of the most popular statistical packages for this kind of analysis is the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Depending on the research goal, the researcher may use different types of analysis. Statistical goals may require hypothesis testing, model building, or descriptive and exploratory analyses. For example, hypothesis testing is based on assumptions regarding the relative truth of the hypothesis; therefore, a data analysis would compare actual outcomes with purported hypotheses.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Extremely varied in nature, qualitative data can include nearly any information that can be captured and is not numerical (Trochim, n.d.-a). Qualitative data are more concerned with describing meaning than with drawing statistical inferences; what is lost in reliability (e.g., faulty transcription or forgotten details) is gained in validity (Holah.co.uk, n.d.). Although qualitative data rely on judgments, they can still be manipulated numerically, much in the same way that quantitative data can be open to judgment (Trochim, n.d.-b).

Some major types of qualitative data include in-depth interviews, direct observation, and written documents. Interviews include individual and focus group interviews and may be recorded. Interviews differ from direct observation in their interactive nature. Direct observation differs from case to case and often means that the researcher does not make contact with the respondent. Written documents might include a variety of written materials, including memos, newspaper clippings, conversation transcripts, and books (Trochim, n.d.-a).

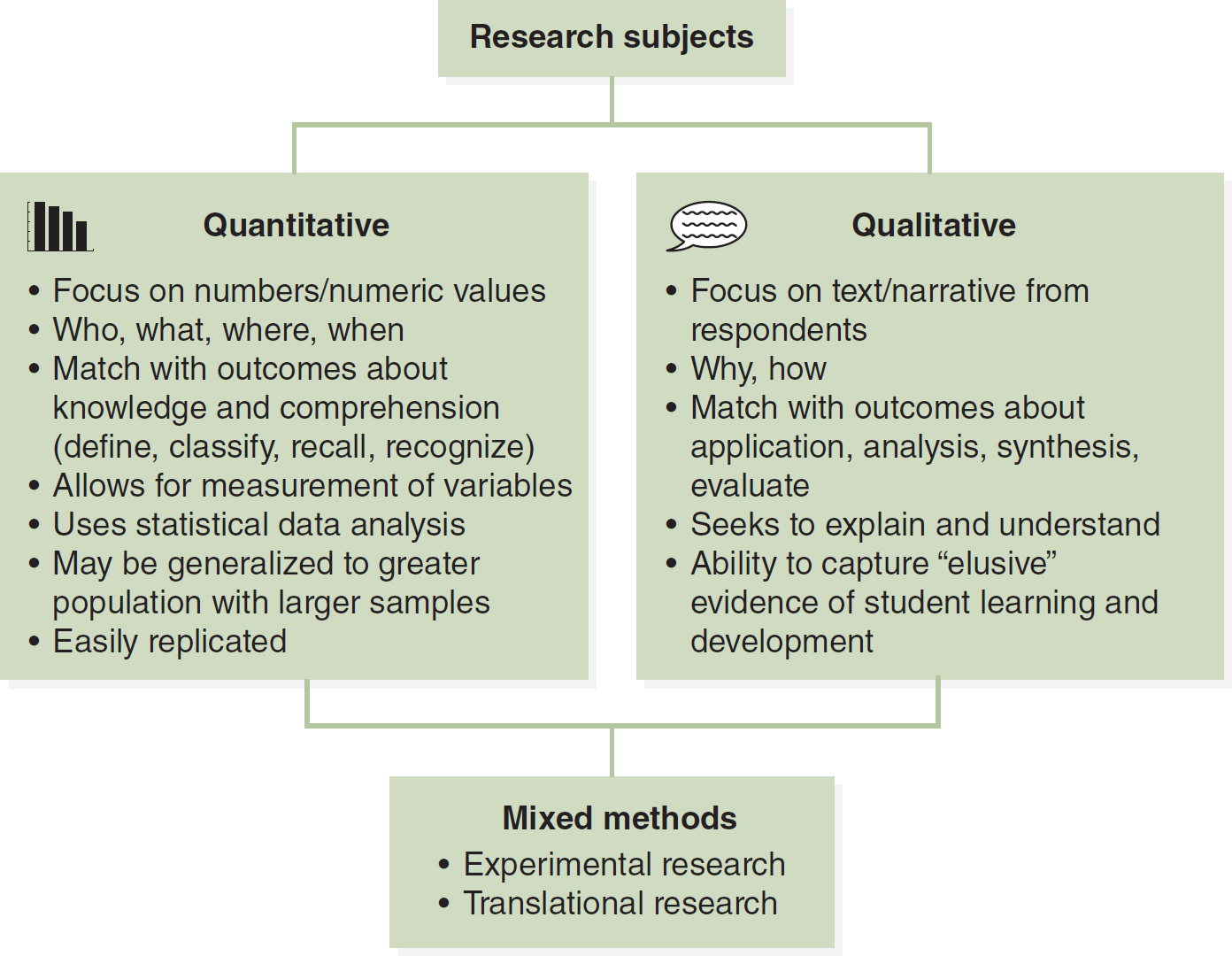

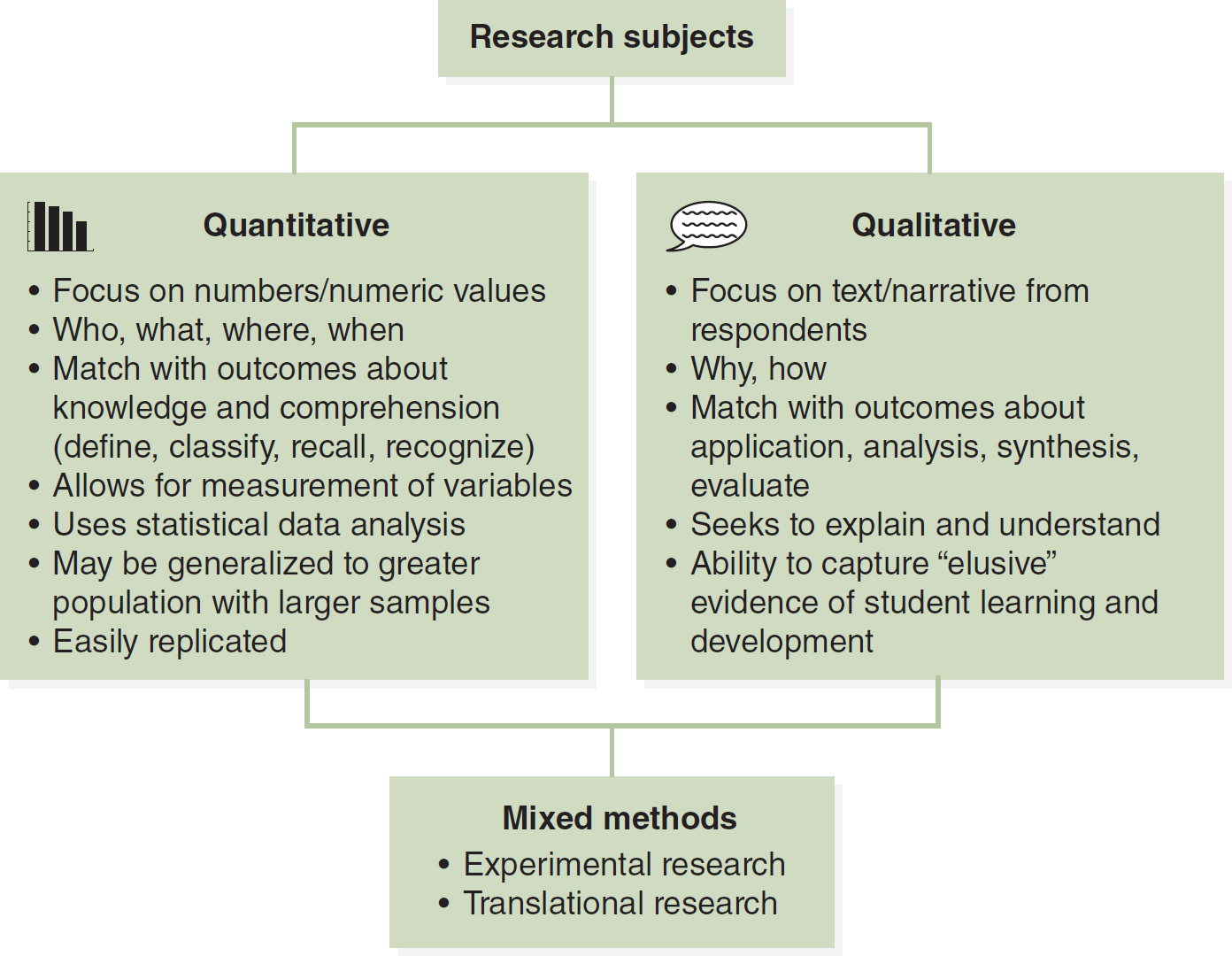

Data analysis is facilitated by computers and specialized programs, such as Excel, Access, or NVivo, in which a user can categorize data and link categories with key words. Data can be converted into information and knowledge by either inductive or deductive reasoning. Most qualitative methods use an inductive approach in which the researcher generates hypotheses (versus the deductive approach typical of quantitative studies, in which hypotheses are tested). Data analysis in quantitative studies may allow the researcher to make inferences to a population beyond the sample as long as the sample was representative of the population. In contrast, generalizing to a larger population is not a goal of qualitative research. Rather, in qualitative research the goals are exploration and deeper understanding of a phenomenon that has not been widely studied (Figure 21-2).

Figure 21-2 Quantitative Versus Qualitative Research

A flowchart illustrates the two research subjects.

The two research subjects are as follows. Quantitative: Focus on numbers and numeric values; Who, what, where, when; Match with outcomes about knowledge and comprehension, define, classify, recall, recognize; Allows for measurement of variables; Uses statistical data analysis; May be generalized to greater population with larger samples; Easily replicated. Qualitative: Focus on text and narrative from respondents; Why, how; Match with outcomes about application, analysis, synthesis, evaluate; Seeks to explain and understand; Ability to capture, elusive, evidence of student learning and development. The two methods converge to form mixed methods, including experimental research and translational research.

Two relatively new approaches to quantitative research are cohort research and case control research. Cohort research is a type of study in which two groups of people are identified, one with an exposure of interest and another without the exposure. The two groups are followed to determine whether the outcome of interest occurs. Groups are defined based on whether they have had an exposure to a particular risk factor. In contrast, case control research is a type of study in which patients who have an outcome of interest and patients who do not have the outcome are identified; the researcher then looks back in time (typically, using health records) to determine exposures and experiences that could have contributed to the outcome occurring or not occurring (Brown, 2014).

The copious amount of data collected in health care is useless if it cannot be analyzed to yield information and knowledge. Big data is a field that deals with ways to examine, analyze, and systematically extract data and information from data sets that are too large or complex to be processed using conventional data-processing application software. The big data revolution challenged healthcare professionals to meaningfully assess the data sets using technical advances to make it easier to collect and analyze information from multiple sources. In health care, data are blended from many sources, such as nurse-managed clinics, hospitals, payers, laboratories, free-standing imaging centers, and physicians' offices. The ability to aggregate this data using advanced data analytics to find better answers is changing the healthcare landscape and how nurses care for their patients.

The Future ⬆ ⬇

The future of NI is growing as fast as technology itself. The more nurses participate in the development process of healthcare technology, the more efficient and effective NI may become. Nurses are urged to take an active role in the profession by providing real-world feedback during the design process and after implementation. Such practical insights will provide valuable data for technology evaluation and advancement in the field of NI.

Summary ⬆ ⬇

This chapter discussed the value of information literacy as an essential research tool and its relationship to knowledge generation and lifelong learning. The reader is now acquainted with informatics tools useful for acquiring new knowledge and assessing previous knowledge and tools useful for collecting, storing, and analyzing information to generate knowledge. In an ideal world, information literacy and informatics tools would be used as a critical skill set for increasing healthcare efficiency, effectiveness, and safety in the 21st century.

| Thought-Provoking Questions |

|---|

- How does information literacy affect NI in the 21st century?

- Provide a detailed description of how NI facilitates both qualitative and quantitative research.

- Reflect on copyright law and why it is needed. Suppose you determine that photographs or other images can be replicated based on your assessment of fair use but your administrative assistant refuses to photocopy them because he feels that it is copyright infringement and against company policy. Describe in detail how you would handle this situation.

- What is big data? How has NI affected data analytics in relation to large data sets?

|

References ⬆

- American Library Association. (2013). Information literacy competency standards for nursing.www.ala.org/acrl/standards/nursing

- Association of College and Research Libraries. (2000, January). Information literacy competency standards for higher education. https://crln.acrl.org/index.php/crlnews/article/view/19242/22395

- Association of College and Research Libraries. (2016, January 11). Framework for information literacy for higher education. www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

- Brackett M. (2015). The data-information-knowledge cycle. DATAVERSITY. www.dataversity.net/the-data-information-knowledge-cycle

- Brown S. (2014). Evidence-based nursing: The research-practice connection (3rd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Eddy L. (2022). New tool transforms data collection for clinical research. Insight. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/articles/new-tool-transforms-data-collection-for-clinical-research

- Holah.co.uk. (n.d.). Quantitative and qualitative data. www.holah.karoo.net/quantitativequalitative.htm

- Kania-Richmond A., Weeks L., Scholten J., & Reney M. (2016). Evaluating the feasibility of using online software to collect patient information in a chiropractic practice-based research network. Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 60(1), 93-105. www.chiropractic.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/95301-1_Chiro_60_1m_Kania-Richmond.pdf

- Laitinen H., Kaunonen M., & Astedt-Kurki P. (2014). Methodological tools for the collection and analysis of participant observation data using grounded theory. Nurse Researcher, 22(2), 10-15. https://journals.rcni.com/doi/abs/10.7748/nr.22.2.10.e1284

- Merrill E. (2015). Integrating technology into nursing education. ABNF Journal, 26(4), 72-73.

- Nash B. (2014). Maintaining the art of nursing in an age of technology. Ohio Nurses Review, 89(6), 12-13.

- Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics. (n.d.). Standardized data: The OMOP common data model. www.ohdsi.org/data-standardization

- Penn State Senior Vice President for Research. (n.d.). IRB guideline X: Guidelines for computer- and internet-based research involving human participants. www.research.psu.edu/irb/policies/guideline10

- Piscotty R., Kalisch B., & Gracey-Thomas A. (2015). Impact of healthcare information technology on nursing practice. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 47(4), 287-293. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12138

- Statistics Canada. (2016, September 30). Data collection and questionnaire. http://web.archive.org/web/20211224063216/https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/cs/questions-3

- Stephens-Lee C., Lu D., and Wilson K. (2013). Preparing students for an electronic workplace. Online Journal of Nursing Informatics, 17(3), 15-27. https://ojni.org/OJNI-V17-N3.pdf

- Teale E., Young J., & Sleigh I. (2013). A point of care electronic stroke data collection system. British Journal of Healthcare Management, 19(1), 10-15. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjhc.2013.19.1.10

- Trochim , W. M. K. (n.d.-a). Research methods knowledge base: Qualitative data. Conjointly. https://conjointly.com/kb/qualitative-data

- Trochim , W. M. K. (n.d.-b). Research methods knowledge base: Types of data. Conjointly. https://conjointly.com/kb/types-of-data

- Werley H. H., Devine E. C., Zorn C. R., Ryan P., & Westra B. L. (1991). The Nursing Minimum Data Set: Abstraction tool for standardized, comparable, essential data. American Journal of Public Health, 81(4), 421-426. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1405031/pdf/amjph00204-0023.pdf