AUTHOR: Imrana Qawi, MD

Sarcoidosis is a chronic multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown cause characterized histologically by the presence of noncaseating granulomas and manifesting with a wide range of clinical disturbances.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Incidence is 11 in 100,000 in whites and 35 in 100,000 in blacks; presents most commonly in the winter and early spring. (The adjusted annual incidence among black Americans is roughly 3 times higher than among white Americans [35.5 cases/100,000, as compared with 10.9/100,000] and is likely more chronic and fatal in black Americans.)

Familial clustering has been described. Having a first-degree relative with sarcoidosis increases the risk for disease fivefold.2 There have been reports of association between sarcoidosis and gene products, specifically human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II antigens, encoded by HLA-DRB1 and DQB1 alleles.3

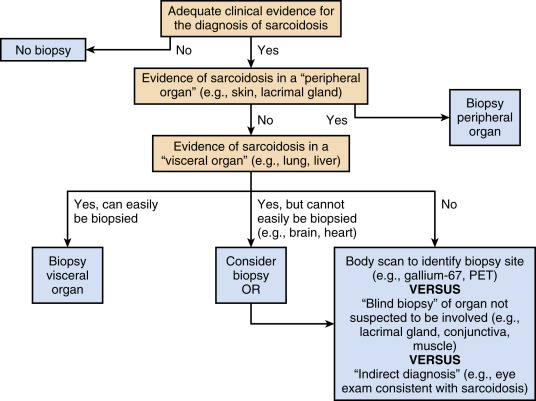

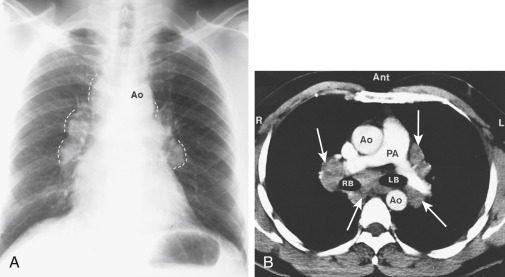

- Clinical manifestations often vary with the stage of the disease and degree of organ involvement. Patients may be asymptomatic, but a chest radiograph may demonstrate findings consistent with sarcoidosis (see “Imaging Studies”). Nearly 50% of patients with sarcoidosis are diagnosed by incidental findings on chest radiograph. Lung involvement occurs in >90% of patients with sarcoidosis.

- Frequent manifestations:

- Pulmonary manifestations: Dry, nonproductive cough; dyspnea; chest discomfort. Pleural effusion is an uncommon manifestation but can occur in stage II or III of pulmonary involvement.

- Constitutional symptoms: Fatigue, weight loss, anorexia, malaise, night sweats.

- Visual disturbances: Blurred vision, ocular discomfort, conjunctivitis, iritis, uveitis (65% of patients).

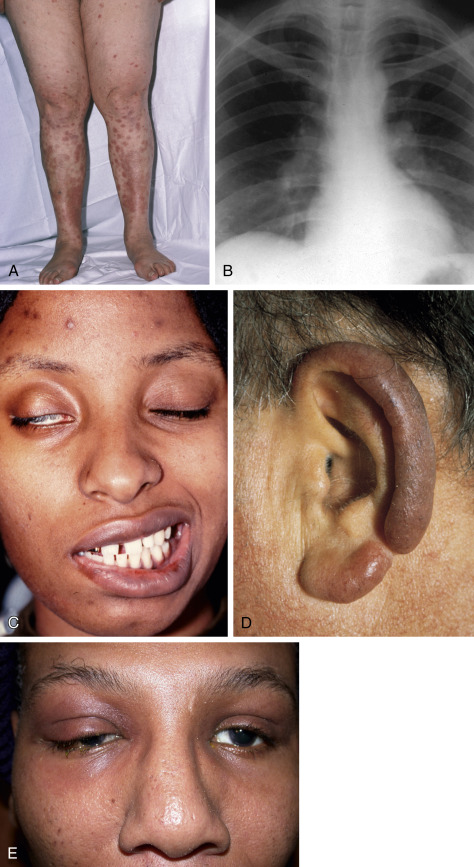

- Dermatologic manifestations (30% of patients): Erythema nodosum (10% of patients), macules, papules, subcutaneous nodules, hyperpigmentation, lupus pernio (indurated violaceous lesions on the nose, lips, ears, and cheeks that can erode into underlying cartilage and bone) (Fig. E1).

- Myocardial disturbances, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, various conduction abnormalities, and pericardial effusion. Cardiac sarcoidosis is much more common than clinically appreciated and is found in up to 25% of patients in the U.S.

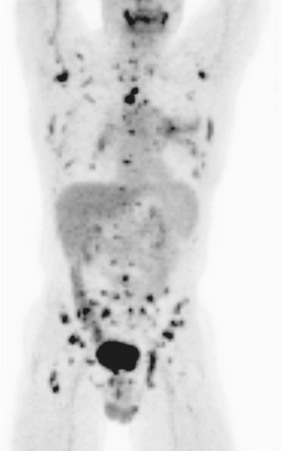

- Splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and rarely, can involve the pancreas.

- Rheumatologic manifestations: Arthralgias have been reported in up to 40% of patients. It typically affects the ankles but can also involve the knees, wrists, and small joints of the hands and feet.

- Löfgren syndrome, consisting of the triad of arthritis, erythema nodosum, and bilateral hilar adenopathy, occurs in 9% to 34% of patients. Fever is frequently present.

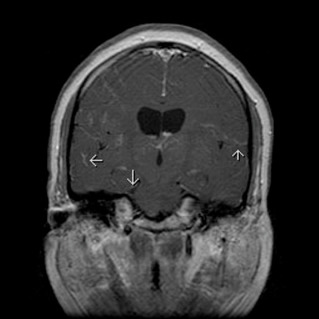

- Neurologic and other manifestations: Cranial nerve palsies, diabetes insipidus, meningeal involvement, parotid enlargement, hypothalamic and pituitary lesions, peripheral adenopathy. Neurosarcoidosis is detected in up to 25% of patients and can occur in the absence of apparent disease elsewhere. Cranial nerve dysfunction is the most common neurologic complication of sarcoidosis. Basilar granulomatous meningitis is the usual cause (Fig. E2), but the facial nerve may also be involved when parotitis is present.

- The presence of anterior uveitis, parotiditis, fevers, and facial nerve palsy is known as Heerfordt syndrome.

- Renal involvement in 7% to 22% in multisystem disease. Epididymis and the testis can be involved in male patients. Initial presentation can be of hydronephrosis due to external compression by retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

- Hypercalcemia is seen in about 10% to 13% of patients with multisystem involvement. Abnormal production of 1-alpha-hydroxylase and PTHrp is thought to contribute to the hypercalcemia in some patients with sarcoidosis. Hypercalciuria is also common.

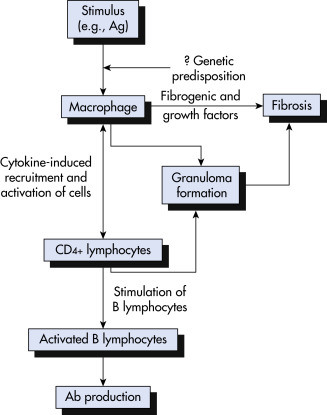

A cardinal feature of sarcoidosis is the presence of CD4+ T cells that interact with antigen-presenting cells to initiate the formation and maintenance of granulomas (Fig. E3). Multiple lines of evidence suggest that sarcoidosis may result from the interaction of multiple genes with environmental exposures or infection.

Figure E3 Simplified proposed pathogenetic sequence in sarcoidosis.

Ab, Antibody; Ag, antigen.

From Weinberger SE: Principles of pulmonary medicine, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

Various HLA antigens have been implicated in diverse patient populations. Familial predisposition has been reported dating back to 1923, with a wide percentage of variability of affected relatives (0.4% to 21%) and heterogeneity based on genetic background. A more recent study was published by the ACCESS (A Case Controlled Etiologic Survey of Sarcoidosis) study group, which confirmed increased risk for family members with an odds ratio of 4.6 for all relatives. Absolute risk, however, for a family member to be affected was less than 1%. This study also showed a higher risk in white versus black American siblings and parents.

Numerous chemokines and cytokines have been implicated in the development and/or resolution of the disease. In sarcoidosis, the alveolitis seen at disease presentation represents an increase in primarily lymphocytic cellularity, predominated by CD4 cells. Presence of increased neutrophils in the bronchoalveolar lavage of patients with sarcoidosis has been associated with persistence of disease, with spontaneous remission noted in 36% of patients with elevated neutrophil counts.