AUTHORS: Kenny Chang, BS and Manuel F. DaSilva, MD

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by inflammatory polyarthritis that affects peripheral joints, especially the small joints of the hands and feet.1 It is a chronic, progressive disease in which untreated inflammation may lead to cartilage and bone erosions and joint destruction resulting in functional impairment.1

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.5% to 1.0% of the worldwide population, with different rates in different ethnic groups2

Female gender, age, tobacco use, silica exposure, and obesity, family history. Smoking has an additive detrimental effect in RA patients (twofold excess mortality risk).2

Usually between age 30 and 50.4 Steadily increases with age until the mid-70s

- Pain, swelling, warmth in one or more peripheral joints, frequently with symmetric small joint involvement, often associated with >1 hour of morning stiffness and constitutional symptoms such as fatigue, malaise, low-grade fevers, and weight loss occurring over a period of weeks to months.4 A subset of patients can also present with acute-onset polyarthritis instead of insidious symptoms.2

- Most common joints involved include metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints (Fig. E1), and metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints (Fig. E2), as well as wrists.4

- Other affected joints involved include elbows, shoulders, hips, knees, and ankles.4

- Distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints are spared.1

- Sacroiliac and vertebral joints are spared, except for the C1 and C2 articulations.4

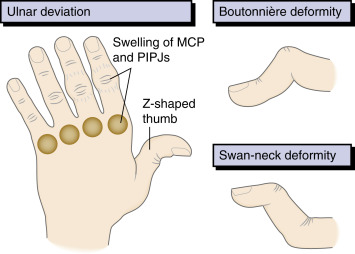

- “Swan-neck” (DIP flexion and PIP hyperextension) (Fig. E3), “boutonniere” (DIP hyperextension and PIP flexion), and “Z-thumb” (MCP flexion and IP hyperextension) deformities (Fig. 4), ulnar deviation, and subluxation of the MCP joints as well as radial deviation of the wrists.

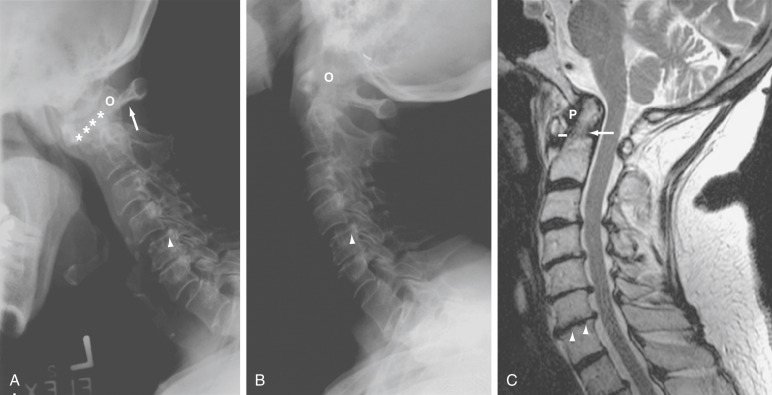

- C1-C2 (atlantoaxial) inflammation can lead to odontoid erosion and transverse ligament laxity/rupture, resulting in atlantoaxial subluxation (Fig. E5) and cord compression.5

- Joint damage of wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, and knees can lead to severe secondary osteoarthritis, necessitating joint surgery and/or replacement.4

Figure 4 Characteristic hand deformities in rheumatoid arthritis.

MCP, Metacarpophalanges; PIPJs, proximal interphalangeal joints.

From Ballinger A: Kumar & Clark’s essentials of clinical medicine, ed 6, Edinburgh, 2012, Saunders.

Extraarticular manifestations:

- Secondary Sjögren syndrome (∼35%): Immune-mediated inflammation of lacrimal and salivary glands, resulting in dry mouth (xerostomia) and eyes (keratoconjunctivitis sicca).6

- Rheumatoid nodules (25%): Nontender, firm nodules on extensor surfaces and pressure points, usually in rheumatoid factor positive (RF+) disease.6 Histopathology demonstrates palisading histiocytes surrounding a central area of fibrinoid necrosis.7

- Felty syndrome: RA with splenomegaly and leukopenia.4 Most patients are positive for HLA-DR4 and RF.

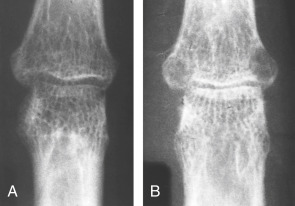

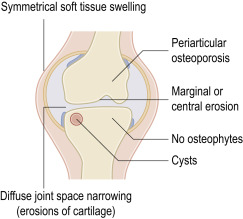

Figure E1 Rheumatoid arthritis.

(A) Initial x-ray shows early trabecular loss around the finger proximal interphalangeal joint with joint space preservation. (B) Subsequently there is erosive change with joint space narrowing.

From Sutton D: Textbook of radiology and imaging, ed 7, 1998, Churchill Livingstone. In Grant LA: Grainger & Allison’s diagnostic radiology essentials, ed 2, 2019, Elsevier.

There is localized osteopenia with a “dot-dash” pattern of deossification (white arrow). Note also the symmetric soft tissue swelling and frank erosion of the ulna border (black arrow).

From Adam A et al: Grainger and Allison’s diagnostic radiology, ed 6, 2015, Elsevier. In Grant LA: Grainger & Allison’s diagnostic radiology essentials, ed 2, 2019, Elsevier.

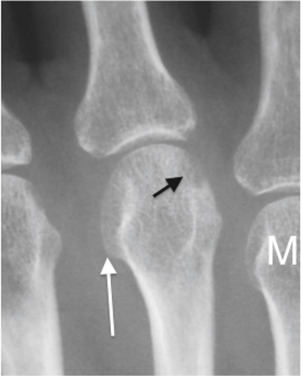

Figure E3 Rheumatoid arthritis.

Bilateral symmetric changes with soft tissue swelling (especially over the ulnar styloids). Erosions are seen at the carpus, metacarpophalangeal joints, distal radius, and ulna with joint space narrowing and bone collapse. There is a swan neck deformity of the right 5th distal interphalangeal joint.

From Sutton D: Textbook of radiology and imaging, ed 7, 1998, Churchill Livingstone. In Grant LA: Grainger & Allison’s diagnostic radiology essentials, ed 2, 2019, Elsevier.

(A and B) Anterior Atlantoaxial Subluxation in RA. (A) Lateral Radiography in Flexion Shows Severe Anterior Atlantoaxial Subluxation with a Wide Anterior Atlantodental Interval (Asterisks) and a Decreased Posterior Atlantodental Interval (Arrow). (B) Almost Complete Reduction of Subluxation is Noted on the Lateral View in Extension. There Also is Subaxial Subluxation at the Level of C4-C5 (Arrowhead) with Erosive Changes in Various Facet Joints. O, Odontoid. (C) T2-Weighted Sagittal Magnetic Resonance (MR) Image in RA Shows Low Signal Periodontoid Pannus (P). The Odontoid Process Appears Irregular Secondary to Erosions (Arrow). The Atlantodental Distance Shows Mild Widening (Solid Line). There Also is Vertical Subluxation Without Signs of Cord Compression. The Anterior Subarachnoid Space is Compromised by Disk Protrusions at Multiple Levels. Small Erosions (Arrowheads) are Seen at the Vertebral End Plates at the C6-C7 Level.

From Firestein GS et al: Firestein & Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology, ed 11, Philadelphia 2021, Elsevier.

- Pleural disease (exudative effusions, pleuritis)4

- Interstitial lung disease (up to 10% clinically significant)4

- Bronchiolitis obliterans4

- Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia4

- Pulmonary nodules: A combination of RA and pneumoconiosis is called Caplan syndrome4

- Entrapment neuropathy (carpal tunnel, tarsal tunnel, and cubital tunnel are most commonly involved)4,8,9

- Mononeuritis multiplex4

- Peripheral neuropathy9

- Cervical myelopathy and cord compression secondary to atlantoaxial subluxation4

- Pachymeningitis (rare)10

- Vasculitis4

- Pericarditis (most common)4

- Myocarditis11

- Valvular nodules11

- There is an increased risk of cardiovascular disease compared to the general population, thought to be secondary to accelerated atherosclerosis from systemic inflammation11

- Keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eye, without dry mouth) (10%)4

- Episcleritis, scleritis, scleral thinning, scleromalacia perforans, ulcerative keratitis4

Amyloidosis: Occurs in longstanding, poorly controlled RA. Usually presents as nephrotic syndrome. Organs affected include the heart, kidney, liver, spleen, intestines, and skin4

Osteoporosis12

The exact cause of RA remains unknown despite extensive research. It is likely that a combination of genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors leads to aberrant immune activation and inflammatory response in the joint. A common genetic background plays a role in susceptibility to disease, as twins and first-degree relatives of RA patients are at an increased risk of developing the disease compared to the general population.13 Patients with HLA-DR4, DR1, and DR14 alleles have increased susceptibility to RA; in particular, one amino acid sequence in the DR β chain, known as the shared epitope, is overrepresented in these patients.13 Other identified genetic associations include polymorphisms in PTPN22, PADI4, CTLA4, TRAF1-C5, STAT4, TNFAIP3.13 Epigenetic factors are also likely to be involved.13 Multiple environmental factors have also been implicated as possible etiologic factors, including cigarette smoking, silica exposure, and low socioeconomic class.13 Infectious agents such as P. gingivalis, Epstein-Barr virus, and parvovirus B19 have also been reported as possible triggers.13

Stages of disease development presumably include:

- Initiation of the innate immune response through toll-like receptor (TLR) activation by a stimulating signal.13 The preclinical stages of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis are characterized by disordered immunity, often associated with mucosal surfaces, including the oral cavity, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract, and by local and systemic generation of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs). These autoantibodies can be detected in the blood a median of 4.5 yr before the onset of arthritis.13a

- Perpetuation of inflammatory response through activation of the adaptive immune system. There is migration of inflammatory cells (autoreactive B and T cells, monocytes) into the joint space, activation of macrophage-like and fibroblast-like synoviocytes, and development of a “synovial pannus,” a thickened synovial membrane.14

- The pannus releases proinflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], interleukin [IL]-1, IL-6, IL-15, IL-17, IL-18) as well as proteases, which erode cartilage and bone.14 Bone erosions are caused mainly by osteoclasts, which express the receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK).13 TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-17 promote the expression of RANK ligand (RANKL) on T cells and fibroblast-like synoviocytes, thus creating a positive feedback loop.13 IL-6 and TNF-α act synergistically to increase vascular endothelial growth factor levels, which in turn stimulate angiogenesis, thereby maintaining pannus formation. B-cell differentiation is also promoted by IL-6, leading to the production of autoantibodies.13

- Many of the new “biologic” disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are engineered to target these cytokines (see “Treatment” section).15