Differential Diagnosis

- Viral causes of arthritis (Table E1):

- Dengue fever: Similar clinical presentation and transmitted by same mosquito

- Chikungunya virus: Similar presentation, albeit with high fever and intense pain in hands, feet, knees, and back; also transmitted by same mosquito

- Parvovirus

- Rubella

- Measles

- Leptospirosis

- Malaria

- Rickettsial infections: African tick bite fever and relapsing fever

TABLE E1 Clinical Features of Zika Virus Compared With Dengue and Chikungunya

| Features | Zika | Dengue | Chikungunya |

|---|

| Fever | + to ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Maculopapular rash | +++ | + | ++ |

| Pruritus | ++ | –/+ | –/+ |

| Conjunctivitis | ++ | – | +/– |

| Arthralgia | ++ | + | +++ |

| Myalgia | + | ++ | + |

| Headache | + | ++ | ++ |

| Facial edema | +/– | ++ | + |

| Palatal petechiae | +/– | ++ | + |

| Hemorrhage | – | ++ | – |

| Shock | – | + | – |

aNote that one study of all three viruses of patients in Nicaragua suggested more similarities among the three viruses with regard to fever, conjunctivitis, arthralgia, and headache.

Primarily adapted from a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Presentation by Ingrid Rabe, Zika Virus: What clinicians need to know: a clinician outreach and communication activity (COCA) call, Atlanta, GA, January 26, 2016.

Workup

- Zika virus infection should be suspected in patients with typical clinical manifestations and a history of exposure to the virus via travel/residence in endemic area or sexual contact with a person from endemic area.

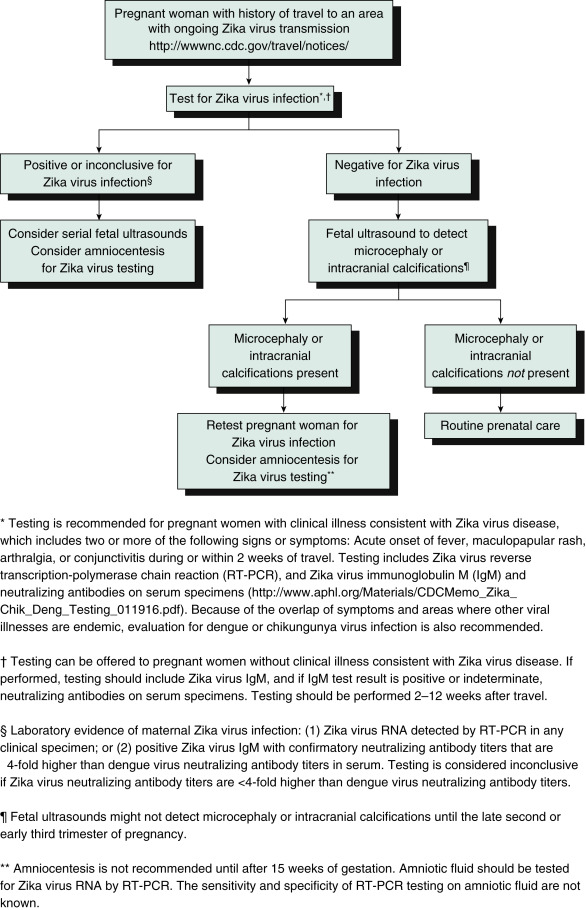

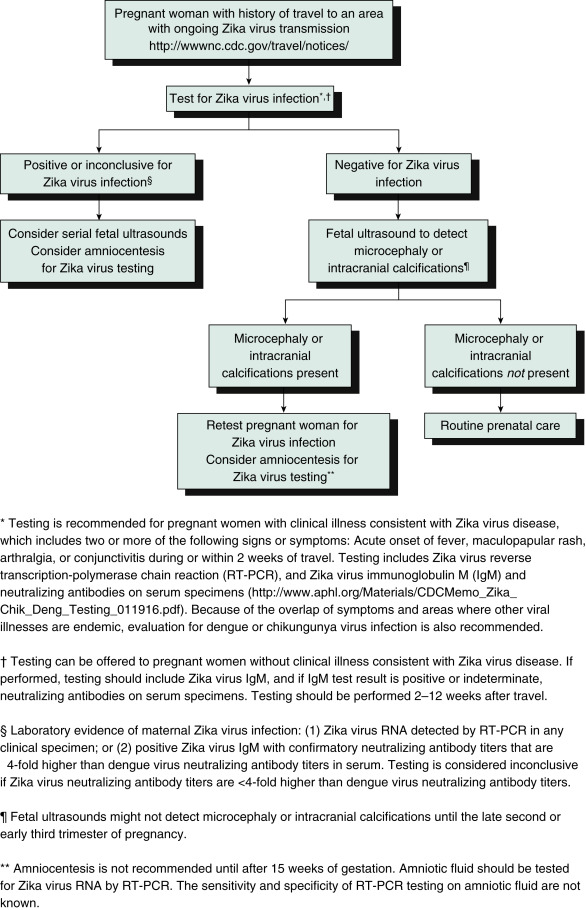

- Fig. E1 illustrates a testing algorithm for a pregnant woman with a history of travel to an area with ongoing Zika virus transmission.

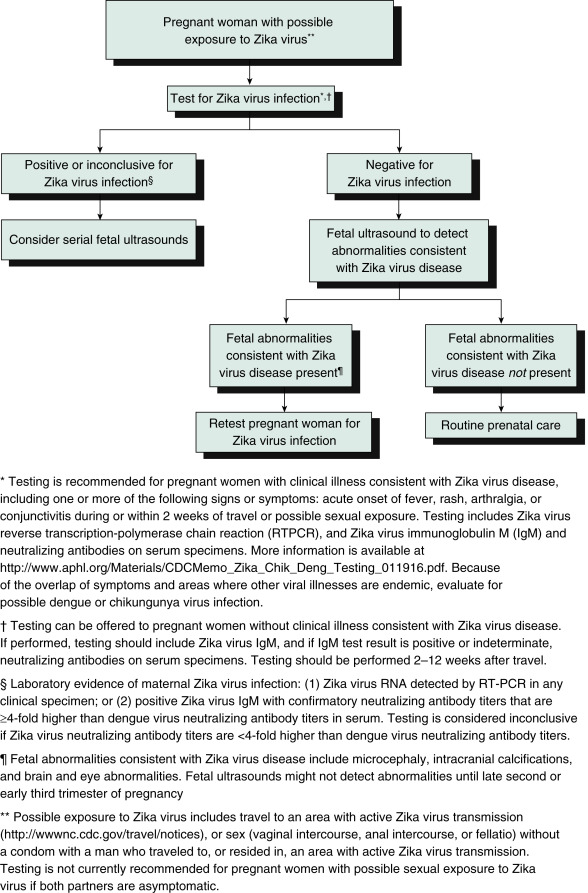

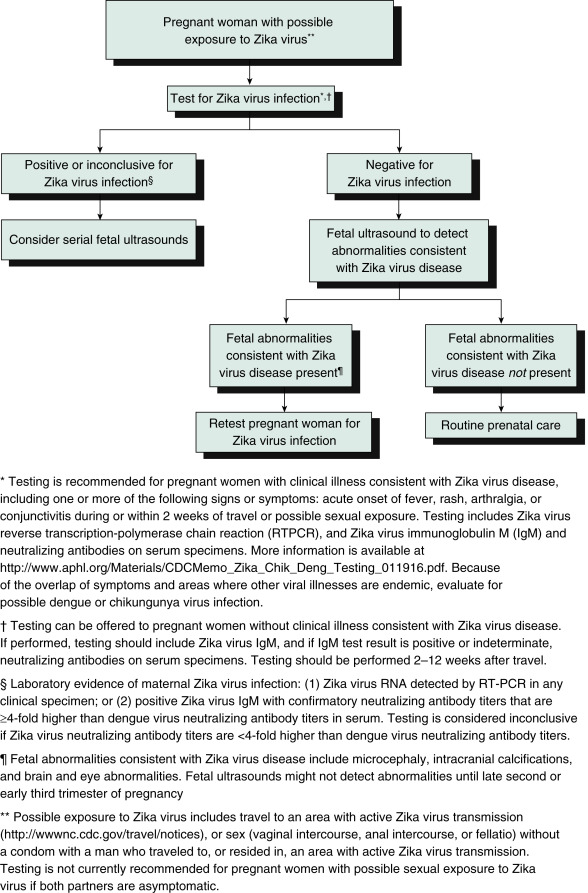

- A testing algorithm for a pregnant woman with possible Zika exposure not residing in an area with active Zika virus transmission is described in Fig. E2.

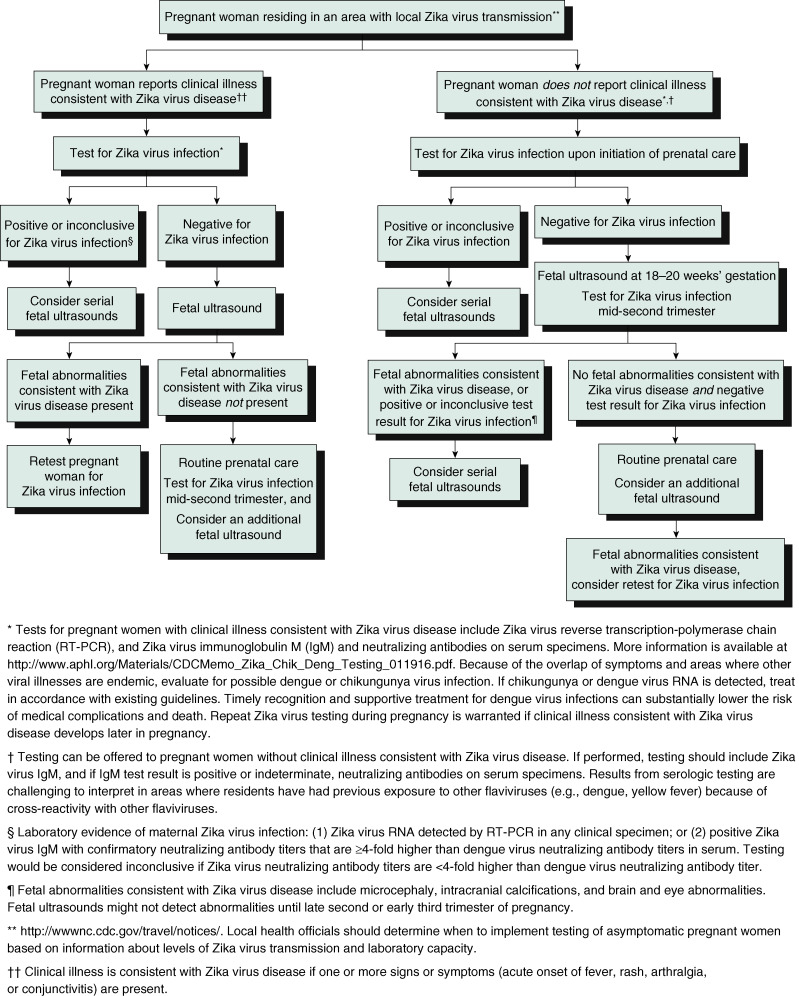

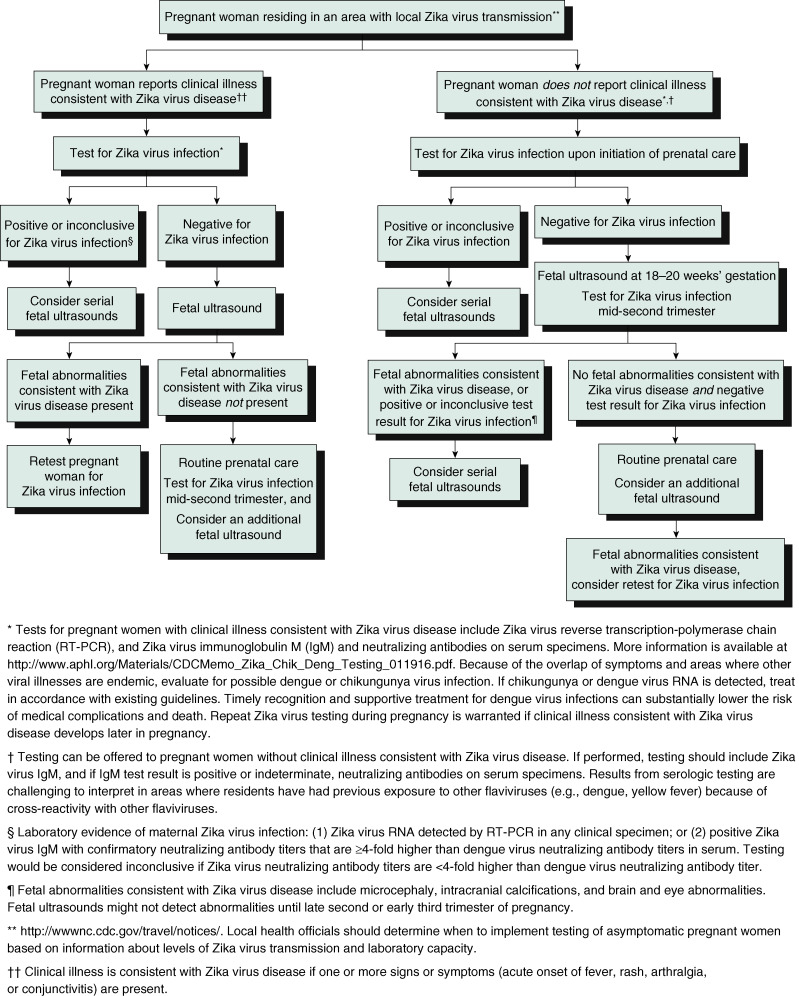

- A testing algorithm for a pregnant woman residing in an area with active Zika virus transmission with or without clinical illness consistent with Zika virus disease is illustrated in Fig. E3.

- Box E1 summarizes recommended Zika virus laboratory testing for infants and children when indicated.

- Recommended clinical evaluation and laboratory testing for infants with possible congenital Zika virus infection is summarized in Box E2.

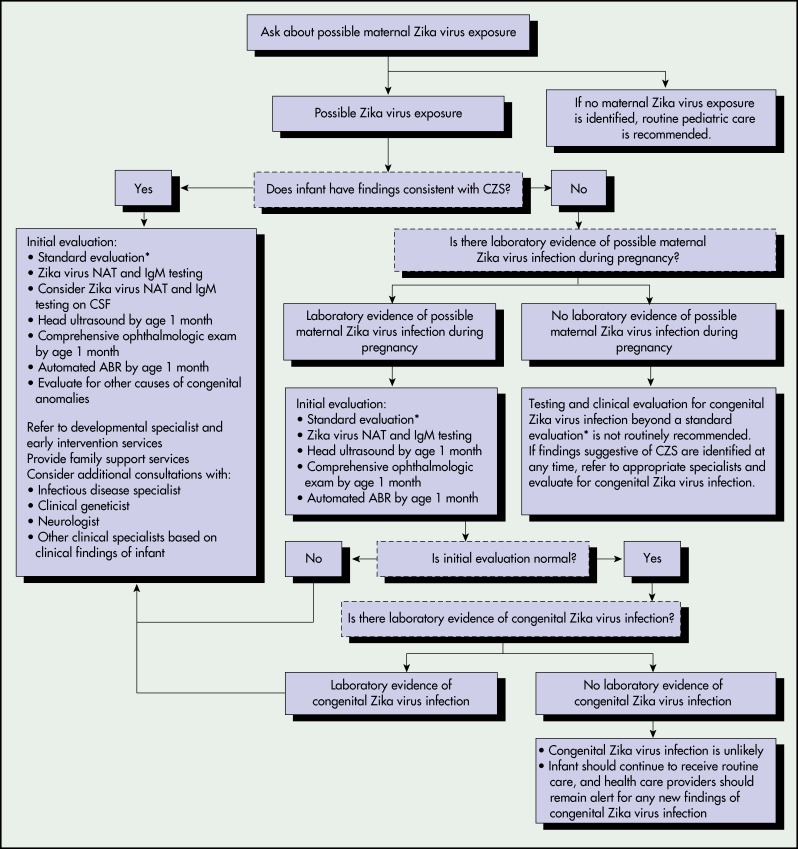

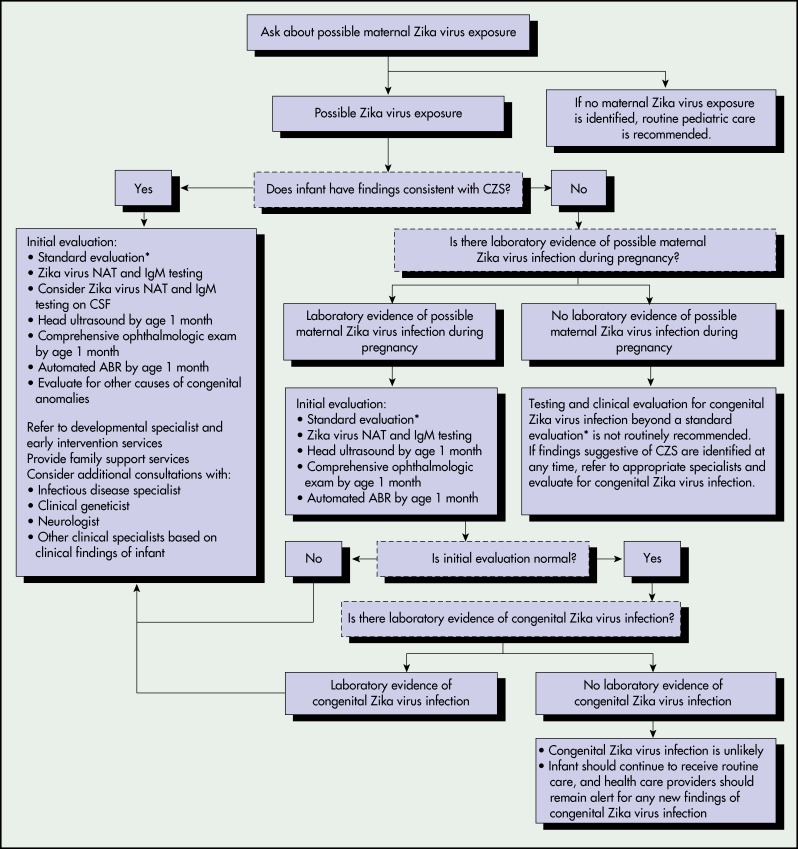

- Fig. E4 illustrates recommendations for the evaluation of infants with possible congenital Zika virus infection based on infant clinical findings.

Figure E1 Updated Interim Guidance: Testing Algorithm,†,§,¶, for a Pregnant Woman with History of Travel to an Area with Ongoing Zika Virus Transmission

From Oduyebo T et al: Update: interim guidelines for health care providers caring for pregnant women and women of reproductive age with possible Zika virus exposure-United States, 2016, MMWR 65[5]:122-127, 2016, fig. 1 p. 124.

Figure E2 Updated Interim Guidance: Testing Algorithm,†,§,¶ for a Pregnant Woman with Possible Zika Virus Exposure Not Residing in an Area with Active Zika Virus Transmission

From Petersen E et al: Update: interim guidelines for health care providers caring for pregnant women and women of reproductive age with possible Zika virus exposure-United States, 2016, MMWR 65[12]:315-322, 2016, fig. 1, p. 319.

Figure E3 Updated Interim Guidance: Testing Algorithm,†,§,¶ for a Pregnant Woman Residing in an Area with Active Zika Virus Transmission, with or Without Clinical Illness†† Consistent with Zika Virus Disease

From Petersen E et al: Update: interim guidelines for health care providers caring for pregnant women and women of reproductive age with possible Zika virus exposure-United States, 2016. MMWR 65(12):315-322, 2016, fig. 2, p. 320.

Figure E4 Recommendations for the Evaluation of Infants with Possible Congenital Zika Virus Infection Based on Infant Clinical Findings,,† Maternal Testing Results,§,¶ and Infant Testing Results,††-US., October 2017. Abr, Auditory Brain Stem Response; CSF, Cerebrospinal Fluid; Czs, Congenital Zika Syndrome; IgM, Immunoglobulin M; Nat, Nucleic Acid Test; Prnt, Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test. All Infants Should Receive a Standard Evaluation at Birth and at Each Subsequent Well-Child Visit by Their Health Care Providers Including (1) Comprehensive Physical Examination, Including Growth Parameters and (2) Age-Appropriate Vision Screening and Developmental Monitoring and Screening Using Validated Tools. Infants Should Receive a Standard Newborn Hearing Screen at Birth, Preferably Using Auditory Brain Stem Response.†automated Abr by Age 1 Mo if Newborn Hearing Screen Passed but Performed with Otoacoustic Emission Methodology.§laboratory Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection During Pregnancy is Defined as (1) Zika Virus Infection Detected by a Zika Virus RNA Nat on any Maternal, Placental, or Fetal Specimen (Referred to as Nat-Confirmed); or (2) Diagnosis of Zika Virus Infection, Timing of Infection Cannot Be Determined or Unspecified Flavivirus Infection, Timing of Infection Cannot Be Determined by Serologic Tests on a Maternal Specimen (I.e., Positive/Equivocal Zika Virus IgM and Zika Virus Prnt Titer 10, Regardless of Dengue Virus Prnt Value; or Negative Zika Virus IgM, and Positive or Equivocal Dengue Virus IgM, and Zika Virus Prnt Titer 10, Regardless of Dengue Virus Prnt Titer). The Use of Prnt for Confirmation of Zika Virus Infection, Including in Pregnant Women, is Not Routinely Recommended in Puerto Rico (Https://www.cdc.gov/Zika/Laboratories/Index.html).¶this Group Includes Women Who Were Never Tested During Pregnancy and Those Whose Test Result was Negative Because of Issues Related to Timing or Sensitivity and Specificity of the Test. Because the Latter Issues are Not Easily Discerned, All Mothers with Possible Exposure to Zika Virus During Pregnancy Who Do Not have Laboratory Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection, Including Those Who Tested Negative with Currently Available Technology, Should Be Considered in This Group.laboratory Testing of Infants for Zika Virus Should Be Performed as Early as Possible, Preferably Within the First Few Days after Birth, and Includes Concurrent Zika Virus Nat in Infant Serum and Urine, and Zika Virus I.M.testing in Serum. If CSF is Obtained for Other Purposes, Zika Virus Nat and Zika Virus I.M.testing Should Be Performed on CSF.††laboratory Evidence of Congenital Zika Virus Infection Includes a Positive Zika Virus Nat or a Nonnegative Zika Virus IgM with Confirmatory Neutralizing Antibody Testing, if Prnt Confirmation is Performed.

From Adebanjo T et al: Update: interim guidance for the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of infants with possible congenital Zika virus infection-United States, 2017, MMWR 66(41):1089-1099, 2017, fig. 1, p. 1093.

BOX E1 Recommended Zika Virus Laboratory Testing for Infants and Children When Indicated1,‡,†

For possible congenital Zika virus infection

- Test infant serum for Zika virus RNA, Zika virus immunoglobulin M (IgM) and neutralizing antibodies and dengue virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies. The initial sample should be collected either from the umbilical cord or directly from the infant within 2 days of birth, if possible.

- If cerebrospinal fluid is obtained for other studies, test for Zika virus RNA, Zika virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies, and dengue virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies.

- Consider histopathologic evaluation of the placenta and umbilical cord with Zika virus immunohistochemical staining on fixed tissue and Zika virus reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on fixed and frozen tissue.

- If not already performed during pregnancy, test mother’s serum for Zika virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies, and dengue virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies.

For possible acute Zika virus disease

- If symptoms have been present for <7 days, test serum (and, if obtained for other reasons, cerebrospinal fluid) for Zika virus RNA by RT-PCR.

- If Zika virus RNA is not detected and symptoms have been present for ≥4 days, test serum (and, if obtained for other reasons, cerebrospinal fluid) for Zika virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies, and dengue virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies.

|

BOX E2 Recommended Clinical Evaluation and Laboratory Testing for Infants With Possible Congenital Zika Virus Infection

CBC, Complete blood count; CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiogram; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

For all infants with possible congenital Zika virus infection, perform the following:

- Comprehensive physical examination, including careful measurement of occipitofrontal circumference, length, weight, and assessment of gestational age.

- Evaluation for neurologic abnormalities, dysmorphic features, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and rash or other skin lesions. Full-body photographs and photographic documentation of any rash, skin lesions, or dysmorphic features should be performed. If an abnormality is noted, consultation with an appropriate specialist is recommended.

- Cranial ultrasound, unless prenatal ultrasound results from third trimester demonstrated no abnormalities of the brain.

- Evaluation of hearing by evoked otoacoustic emissions testing or auditory brainstem response testing, either before discharge from the hospital or within 1 mo after birth. Infants with abnormal initial hearing screens should be referred to an audiologist for further evaluation.

- Ophthalmologic evaluation, including examination of the retina, either before discharge from the hospital or within 1 mo after birth. Infants with abnormal initial eye evaluation should be referred to a pediatric ophthalmologist for further evaluation.

- Other evaluations specific to the infant’s clinical presentation.

For infants with microcephaly or intracranial calcifications, additional evaluation includes the following:

- Consultation with a clinical geneticist or dysmorphologist.

- Consultation with a pediatric neurologist to determine appropriate brain imaging and additional evaluation (e.g., ultrasound, CT scan, MRI, and ECG).

- Testing for other congenital infections such as syphilis, toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus infection, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection, and herpes simplex virus infections. Consider consulting a pediatric infectious disease specialist.

- CBC with platelet count and liver function and enzyme tests, including alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and bilirubin.

- Consideration of genetic and other teratogenic causes based on additional congenital anomalies that are identified through clinical examination and imaging studies.

|

Adapted from Staples JE et al: Interim guidelines for the evaluation and testing of infants with possible congenital Zika virus infection-United States, MMWR 65(3):63-67, 2016.