AUTHOR: Glenn G. Fort, MD, MPH

Dengue fever (DF) is an infectious disease endemic in most tropical and subtropical countries. It is the most widespread arboviral illness worldwide. The causative agent is the dengue virus, a single positive-stranded RNA virus of the Flaviviridae family, which has four distinct but closely related serotypes (DEN-1, DEN-2, DEN-3, DEN-4). Dengue virus is transmitted by the Aedes mosquito. The primary vector is Aedes aegypti; the secondary vector is Aedes albopictus. The case definitions of dengue are summarized in Table E1.

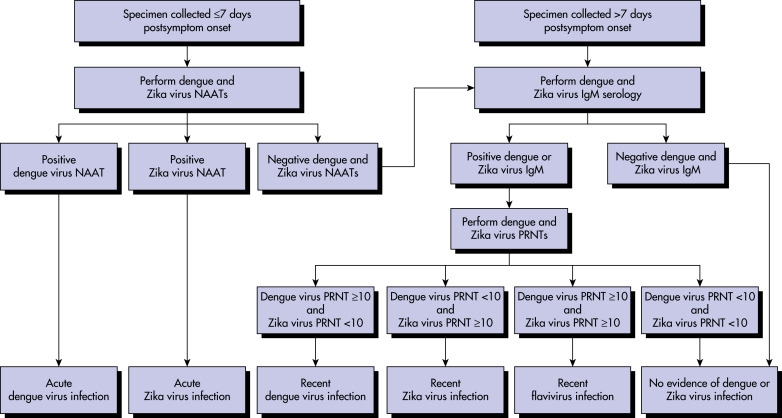

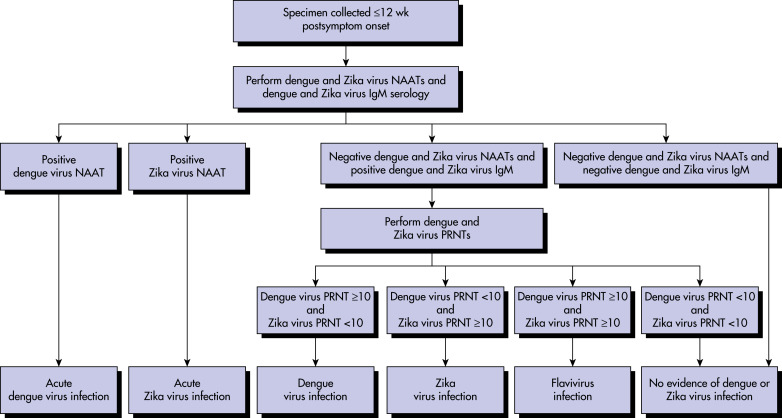

TABLE E1 Case Definitions for Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever/Dengue Shock Syndrome, Severe Dengue, and the Warning Signs for Severe Dengue

ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate transaminase.

From Ryan ET et al: Hunter’s tropical medicine and emerging infectious diseases, ed 10, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

- The incidence of dengue is underestimated. Recent estimates indicate 390 million dengue infections per year, of which 96 million manifest clinically. Attack rates during epidemics range from 1 to 10/1000 per year and as high as 292/1000 among children in hyperendemic countries. There has been a thirtyfold increased incidence over the past 30 yr. During 2010-2017, a total of 5387 dengue cases were reported from U.S. states; 93% were travel-associated. In 2021, there were a 117 cases in the U.S. from travel (states with the most cases were Florida: 19, California: 17, New York: 10, New Jersey: 10, and Texas: 10) and 513 cases in U.S. territories of which 509 were locally acquired in Puerto Rico. Dengue is endemic in more than 100 countries in the regions of Africa, Asia, and West Pacific. Outbreaks have also occurred in Europe.

- Dengue shows cyclical variation with large outbreaks every 3 to 5 yr. DF is confirmed in up to 8% of febrile travelers returning from the tropics.

Travel to endemic regions. Few locally acquired U.S. cases have been documented in Texas, Hawaii, and Florida. The majority of indigenous cases presented as uncomplicated fever, and a minor percentage developed dengue hemorrhage fever (DHF) or dengue shock syndrome (DSS). Local transmission has also been reported in recent years in Europe (Southern France, Croatia, and Portugal).

- Clinical presentation ranges from asymptomatic infection to shock syndrome.

- Symptomatic DF infection can be classified into three categories:

- Undifferentiated fever.

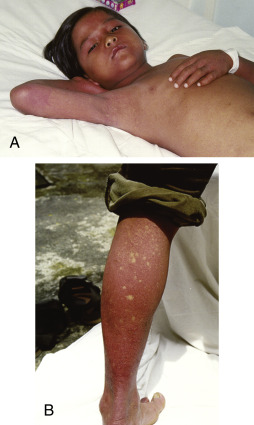

- Classic DF: Characterized by acute febrile illness accompanied by symptoms such as headache, retroorbital pain, fatigue, mild respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms, and myalgias or arthralgias (“break bone fever”); DF usually follows an incubation period of 3 to 14 days, and fever typically lasts 5 to 7 days; physical findings may include a maculopapular rash (Fig. E1), lymphadenopathy, pharyngeal erythema, and injected conjunctivae; some patients may experience development of hemorrhagic manifestations with petechiae, purpura (Fig. E2), and rarely, epistaxis, gum bleeding, and gastrointestinal bleeding; during pregnancy, DF has been associated with increased risk for premature labor and birth, uterine hemorrhage, intrauterine death, neonatal death, and maternofetal transmission.

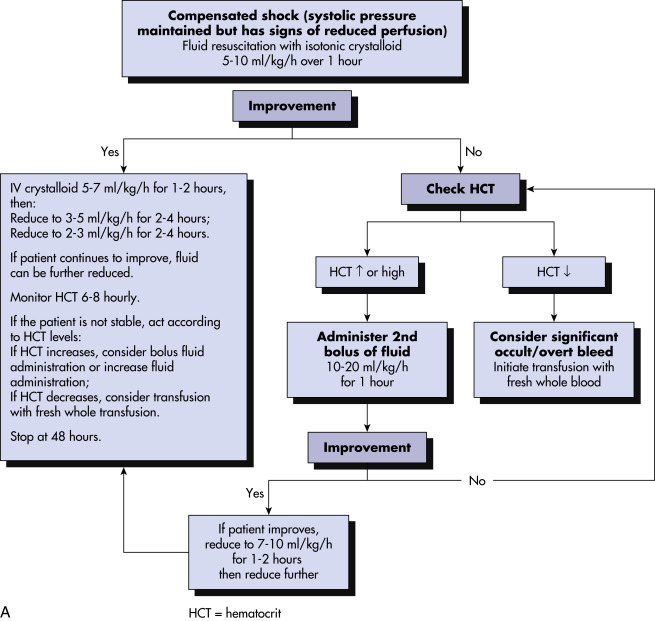

- DHF/DSS: Occurs in fewer than 3% of infected individuals; early course is similar to presentation of classic dengue, but 4 to 7 days after onset of illness, plasma leakage with hemorrhagic manifestations develops, resulting in hypoproteinemia, peripheral edema, ascites, and pleural and cardiac effusions, and is suggested by a hematocrit increase of 20% during course of illness; thrombocytopenia is also a hallmark, with resultant clinical manifestations such as petechiae, ecchymosis, mucosal hemorrhage, and GI bleeding; may progress to DSS with circulatory collapse, manifested by rapid/weak pulse, profound hypotension, and pulse pressure of <20 mm Hg; warning signs for DHF/DSS include mucosal bleed, abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, abrupt defervescence, change in mental status, and respiratory distress.

Figure E1 Characteristic skin manifestations in convalescent dengue.

A, Early convalescent macular diffuse rash occurring in the first week after recovery. B, Typical convalescent rash with “islands of white in a sea of red.”

From Vincent JL et al: Textbook of critical care, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2011, Saunders.

Figure E2 Acute skin manifestations of dengue.

A, Characteristic minor bleeding near injection sites. B, Rash in established dengue shock syndrome. C, Severe bleeding after intravenous (IV) injection. Staff should press after IV injections for 5 min to ensure that bleeding stops.

From Vincent JL et al: Textbook of critical care, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2011, Saunders.

After a bite by infected mosquito, the virus replicates in regional lymph nodes and then spreads by blood and the lymphatic system to other tissues. The incubation period is typically 4 to 7 days (range, 3 to 14 days). The most important risk factors for development of severe disease (DHF/DSS) are young age, female sex, prior infection, and viral genotype. The majority of DHF/DSS cases occur during secondary heterologous (different from first exposure) infection or during primary infection in infants born to dengue-immune mothers. In such cases, non-neutralizing cross-reactive antibodies facilitate viral entry into cells, generating higher viral burdens and stronger inflammatory responses. Additionally, T-memory cells from a previous infection are preferentially expanded because of a lower threshold of activation compared with naïve T cells of higher affinity to the current serotype. This results in suboptimal clearance of the virus and quicker, more robust cytokine production, leading to increased vascular permeability and plasma leakage. “Asian” genotypes DEN-2 and DEN-3 are associated with severe disease.