Diagnosis of PID is made when a sexually active female has clinical or pathologic evidence of upper genital tract infection and inflammation, which includes any cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, or adnexal tenderness. Box 1 summarizes the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria for diagnosing PID. Although no single test or measure reliably diagnoses the spectrum of disorders that comprise PID, a clinical diagnosis of symptomatic PID has a positive predictive value of 65% to 90%:

- Providers should maintain a low threshold for diagnosis and treatment of PID given significant long-term health risks associated with the disease, especially if untreated

- The CDC suggests that women with risk factors, abdominal or pelvic pain, and any pelvic tenderness (cervical, uterine, and/or adnexal) be treated for PID

- Definitive criteria for diagnosis of PID include:

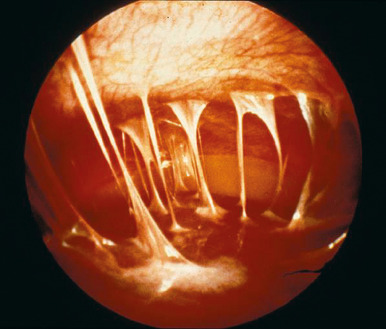

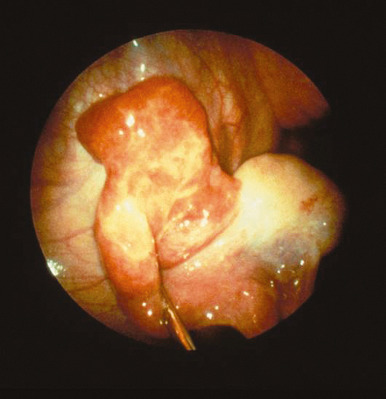

- Laparoscopic abnormalities consistent with PID

- Histopathologic evidence of endometritis in women with clinical suspicion for PID

- Transvaginal sonography or other imaging techniques showing thickened, fluid-filled tubes with or without free pelvic fluid or tuboovarian complex or Doppler studies indicative of pelvic infection such as tubal hyperemia

BOX 1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidelines for Diagnosis of Acute Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: Clinical Criteria for Initiating Therapy

MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging; PID, pelvic inflammatory disease; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; WBCs, white blood cells.

Minimum criteriaEmpirical treatment of PID should be initiated in sexually active young women and others at risk for STIs if the following minimum criteria are present and no other causes(s) for the illness can be identified: - Lower abdominal tenderness or

- Adnexal tenderness or

- Cervical motion tenderness

Additional criteria for diagnosing PID

- Oral temperature >38° C (100.4° F)

- Abnormal cervical or vaginal discharge (mucopurulent)

- Presence of abundant WBCs on microscopy of vaginal secretions

- Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Elevated C-reactive protein

- Laboratory documentation of cervical infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis

Definitive criteria for diagnosing PID

- Histopathologic evidence of endometritis on endometrial biopsy

- Transvaginal sonography or MRI showing thickened fluid-filled tubes, with or without free pelvic fluid or tuboovarian complex

- Laparoscopic abnormalities consistent with PID

- Although initial treatment can be made before bacteriologic diagnosis of C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae infection, such a diagnosis emphasizes the need to treat sex partners.

|

From Gershenson DM et al: Comprehensive gynecology, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.Data from Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015, MMWR Recomm Rep 64(RR-03):1-137, 2015.

However, requiring the aforementioned criteria before empiric treatment would not only lead to underdiagnosis and treatment but also delay treatment and lead to unnecessary morbidity.

- Supportive criteria for that enhance diagnostic specificity of PID include:

- Oral temperature >38.3° C (>101° F)

- Abnormal cervical mucopurulent discharge or cervical friability

- Predominance of white blood cells (WBCs)on saline microscopy of vaginal fluid

- Elevated acute inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] or C-reactive protein)

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis infection

Differential Diagnosis

- Appendicitis

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Intrauterine/other pregnancy

- Ovarian cyst

- Adnexal torsion

- Endometriosis

- Urinary tract infection (cystitis or pyelonephritis)

Workup

- History: As in risk factors and clinical presentation, previously

- Physical examination: As in physical findings, previously

Laboratory Tests

- Wet mount: Clue cells, increased WBCs

- Gram stain of endocervical exudate: >30 polymorphonuclear cells per high-power field correlates with chlamydial or gonococcal infection

- Endocervical cultures for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis

- CBC: Leukocytosis

- Human chorionic gonadotropin to rule out intrauterine or ectopic pregnancy

- Elevated acute phase reactants: ESR >15 mm/h, C-reactive protein

- HIV and rapid plasma reagin, with consideration for other STI screening such as hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C Ab (HIV increases incidence of tuboovarian abscess [TOA])

- Fallopian tube aspirate or peritoneal exudate culture if laparoscopy or drainage of TOA performed

- Endometritis on endometrial biopsy if performed

Imaging StudiesUltrasonography is commonly used to assess for PID and can be used to determine inpatient vs. outpatient treatment by presence or absence of TOA. Findings include:

- Thick-walled adnexal mass with heterogenous or cystic contents suggestive of abscess

- Dilated fallopian tubes (note that normal fallopian tubes are rarely identified on ultrasonography)

- “Cogwheel sign” indicating thickened fallopian tube walls

- Heterogenous fluid within the endometrium

Computed tomography or MRI scan may be useful to better characterize adnexal masses and/or rule out other pathology, such as appendicitis or renal calculus. Choice of imaging modality will depend on clinical suspicion, logistical access, and associated cost.

ProceduresEndometrial biopsy that reveals endometritis may support a diagnosis of PID. Laparoscopy has been utilized as a gold standard for diagnosing PID, but due to the invasive nature of this procedure and the risks and costs associated, it is rarely indicated as a diagnostic tool.