AUTHORS: Maya Deeb, MD and Talia Zenlea, MD

Ascites is a pathologic accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity, most commonly due to portal hypertension caused by cirrhosis.

- Diuretic-resistant ascites: Ascites that cannot be mobilized or the early occurrence of ascites that cannot be prevented because of a lack of response to dietary sodium restriction and intensive diuretic treatment

- Diuretic-intractable ascites: Ascites that cannot be mobilized or the early recurrence of ascites that cannot be prevented because of the development of diuretic-induced complications that preclude the use of effective doses of diuretics

- Ascites may be graded according to the amount of fluid in the peritoneal cavity1,2:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ascites is the most common decompensation-defining complication of cirrhosis and is associated with worse prognosis. Ascites occurs at a rate of 7% to 10% annually in cirrhotic patients and occurs in ∼60% of individuals with cirrhosis within 10 yr of diagnosis.3 Cirrhosis is the cause of more than 80% of cases of ascites.4

- Important information to elicit within history:

- History of viral hepatitis

- Ongoing or previous heavy alcohol use

- Current or previous intravenous drug use and/or intranasal cocaine use

- Sexual history (e.g., unprotected sex with multiple partners, men who have sex with men)

- History of transfusions, tattoos, piercings, or incarceration

- Travel history and time spent in endemic regions for hepatitis

- Symptoms suggestive of peritoneal malignancy (e.g., weight loss, pain, palpable masses, rectal/vaginal bleeding)

- Other liver disease symptoms (e.g., increasing abdominal girth, jaundice, pruritus, confusion, pedal edema)

- Cardiac symptoms (e.g., pedal edema, shortness of breath, orthopnea, chest pain)

- Hypothyroid disease (fatigue, weight gain, constipation)

- History of ascites, prior treatment, large volume paracentesis (LVP) requirements and frequency

- Important physical exam findings:

- Protuberant abdomen (Fig. E1)

- Bulging flanks (can be present in obesity)

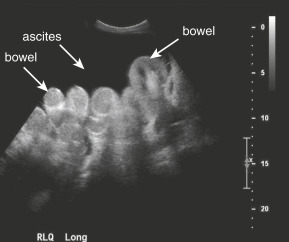

- Flank dullness to percussion (requires ∼1500 mL of fluid)

- Fluid wave on abdominal exam

- Lower extremity edema

- Shifting dullness on abdominal exam

- Physical signs associated with liver cirrhosis: Spider angiomas, jaundice, loss of body hair, skeletal muscle wasting (sarcopenia), Dupuytren contracture, bruising, palmar erythema, gynecomastia, testicular atrophy, rectal varices, and caput medusa

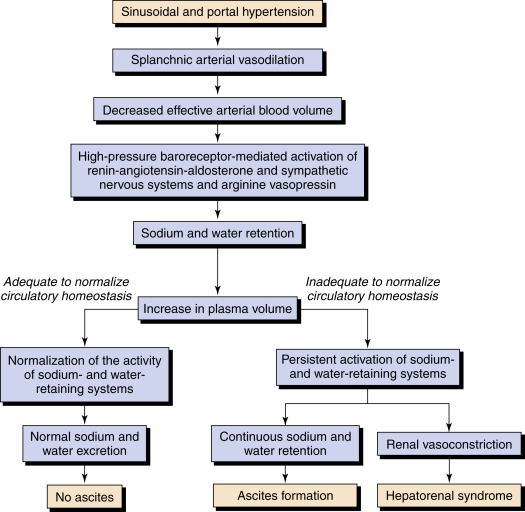

Pathophysiology of ascites (Fig. E2): Increased hepatic resistance to portal flow leads to portal hypertension. A portal pressure >12 mm Hg appears to be required for fluid retention.5 The splanchnic vessels respond by increased secretion of nitric oxide, causing splanchnic artery vasodilation. Vasodilation appears also to be mediated by the translocation of enteric bacteria and bacterial products. Early in the disease, increased plasma volume and increased cardiac output compensate for this vasodilation. However, as the disease progresses, the effective arterial blood volume decreases, causing sodium and fluid retention through activation of the renin-angiotensin system. Over time, activation of the sympathetic system causes renal vascular perfusion to decrease and may lead to hepatorenal syndrome. The change in capillary pressure causes increased permeability and retention of fluid in the abdomen.5 Principal causes of ascites formation categorized by underlying pathophysiology are summarized in Box E1.

BOX E1 Principal Causes of Ascites Formation Categorized by Underlying Pathophysiology

From Townsend CM et al: Sabiston textbook of surgery, ed 21, St Louis, 2022, Elsevier.