AUTHOR: David J. Lucier Jr., MD, MBA, MPH

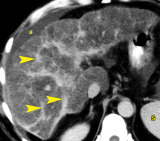

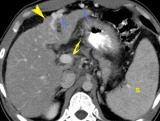

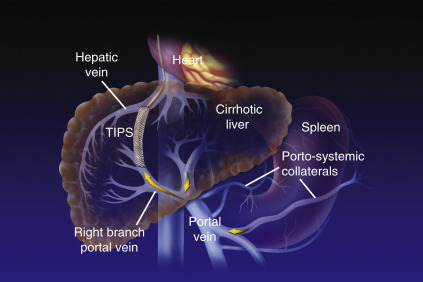

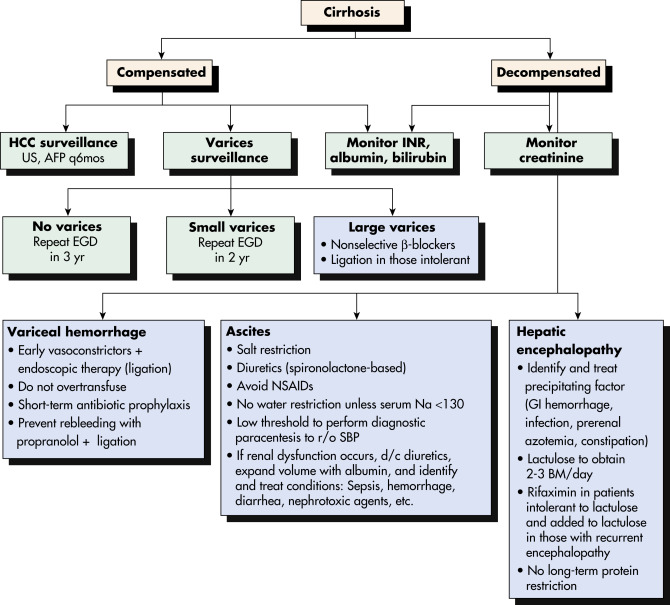

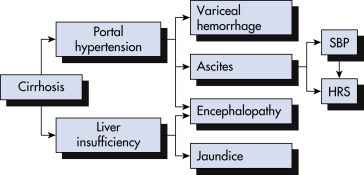

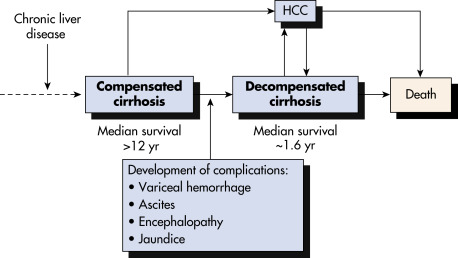

Cirrhosis is defined histologically as the presence of irreversible fibrosis in the liver. It can be classified as micronodular, macronodular, or mixed; however, each form may be seen in the same patient at different stages of the disease, and this classification system has little utility in determining the underlying etiology of cirrhosis. Cirrhosis manifests clinically with portal hypertension, ascites and peripheral edema, hepatic encephalopathy, and variceal bleeding.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Cirrhosis was the fourteenth-leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2015 and the thirteenth-leading cause of death globally. In the U.S., cirrhosis-related deaths increased 3.4% annually between 2009 and 2016.

- Alcohol abuse, hepatitis C, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are the major causes of cirrhosis in the U.S.

- Economic burden of cirrhosis in the U.S. exceeds $2 billion in direct costs and over $10 billion in indirect costs.

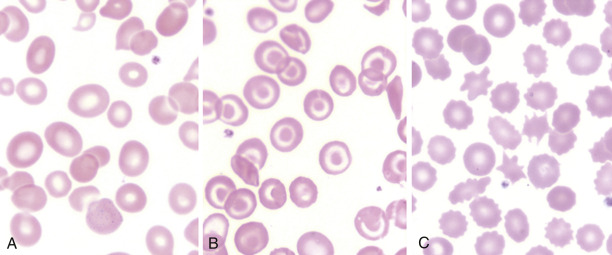

Jaundice, palmar erythema, spider angiomata, ecchymosis (thrombocytopenia or coagulation factor deficiency), increased pigmentation (hemochromatosis), xanthomas (primary biliary cirrhosis), and diffuse pruritus. Cutaneous lesions often accompany cirrhosis and can be found in >40% of people with chronic alcoholism

Kayser-Fleischer rings (corneal copper deposition seen in Wilson disease; best diagnosed with slit lamp examination), scleral icterus

Tender or nontender hepatomegaly (congestive hepatomegaly), small, nodular liver (cirrhosis), palpable, nontender gallbladder (neoplastic extrahepatic biliary obstruction), palpable spleen (portal hypertension), dilated superficial periumbilical vein (caput medusae), venous hum auscultated over periumbilical veins (portal hypertension), ascites (portal hypertension, hypoalbuminemia), diffuse abdominal tenderness (spontaneous bacterial peritonitis)

Hemorrhoids (portal hypertension), guaiac-positive stools (alcoholic gastritis, bleeding esophageal varices, peptic ulcer disease, bleeding hemorrhoids, portal gastropathy)

- Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection

- Alcoholism

- Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- Primary biliary cholangitis

- Secondary biliary cirrhosis, obstruction of the common bile duct (stone, stricture, pancreatitis, neoplasm, sclerosing cholangitis)

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Drugs with chronic hepatitis (e.g., acetaminophen, isoniazid, methotrexate, methyldopa)

- Chronic hepatic congestion (e.g., congestive heart failure [CHF], constrictive pericarditis, tricuspid insufficiency, thrombosis of the hepatic vein, obstruction of the vena cava)

- Hemochromatosis

- Wilson disease

- Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency

- Infiltrative diseases (amyloidosis, glycogen storage diseases, nonhepatocellular malignancies)

- Nutritional: Jejunoileal bypass

- Others: Parasitic infections (schistosomiasis), idiopathic portal hypertension, congenital hepatic fibrosis, systemic mastocytosis