AUTHOR: Fred F. Ferri, MD

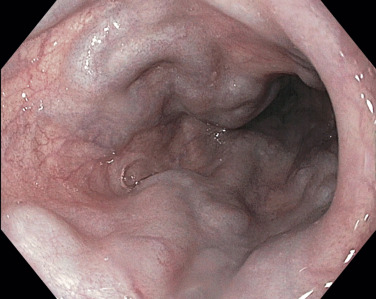

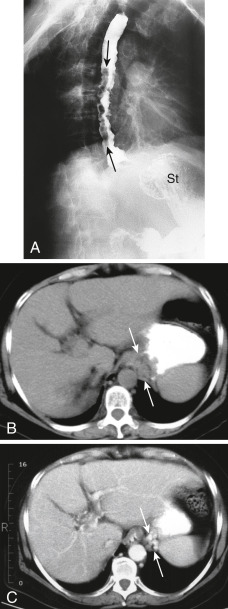

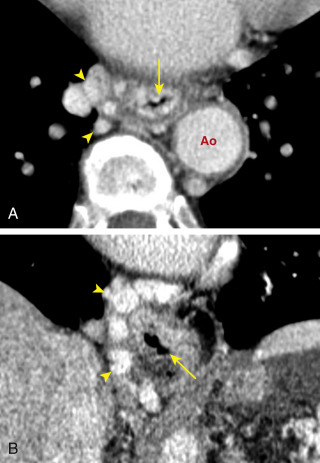

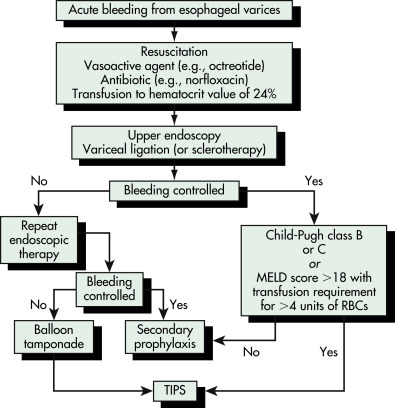

Esophageal varices are dilated submucosal veins that occur in patients with underlying portal hypertension, function as a shunt between the portal venous and systemic venous circulation, and can result in severe upper GI hemorrhage.

| ||||||||||||

- Often asymptomatic until acute upper GI hemorrhage: Hematemesis, hypovolemia

- No physical findings specific for esophageal varices

- Stigmata of cirrhosis and portal hypertension may be evident: Palmar erythema, telangiectasias, gynecomastia, testicular atrophy, jaundice, caput medusae, lower extremity edema, ascites, splenomegaly, hemorrhoids, asterixis

- Portal hypertension results from obstruction to portal venous outflow, and varices subsequently develop in order to decompress the hypertensive portal vein and return blood to the systemic circulation.

- Varices may appear when portal vein pressures rise above 10 to 12 mm Hg.

- Cirrhosis is the most common cause of portal hypertension.