AUTHOR: Fred F. Ferri, MD

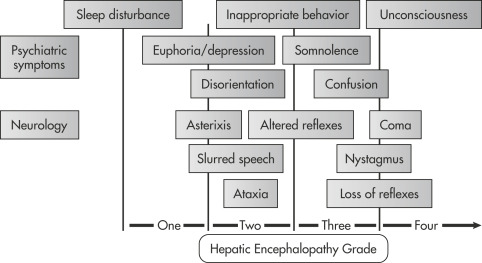

Hepatic encephalopathy is a neuropsychiatric syndrome occurring in patients with severe impairment of liver function and consequent accumulation of toxic products not metabolized by the liver. It is characterized by gradual impairment of the ability to perform mental tasks and to react to external stimuli. Fig. 1 illustrates the hepatic encephalopathy grades in acute liver failure. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy refers to patients with hepatic cirrhosis and mild cognitive impairment, but no history of overt encephalopathy.

Portal systemic encephalopathy

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hepatic encephalopathy can be classified by clinical stages described in Table 1. Other widely used scales are the four score criteria and the West Haven criteria. The West Haven criteria for grading hepatic encephalopathy is as follows:

- Grade (0): No abnormalities noted

- Grade (1): Unawareness (mild), euphoria or anxiety, shortened attention span, impairment of calculation ability, lethargy, or apathy

- Grade (2): Disorientation to time, obvious personality change, inappropriate behavior

- Grade (3): Somnolence to stupor, responsiveness to stimuli, gross disorientation, bizarre behavior

- Grade (4): Coma

TABLE 1 Clinical Stages of Hepatic Encephalopathy

| Stage | Asterixis | EEG Changes | Clinical Manifestations |

|---|---|---|---|

| I (prodrome) | Slight | Minimal | Mild intellectual impairment, disturbed sleep-wake cycle |

| II (impending) | Easily elicited | Usually generalized | Drowsiness, confusion, coma/inappropriate behavior, disorientation, mood swings |

| III (stupor) | Present if patient cooperative | Grossly abnormal slowing of rhythm | Drowsy, unresponsive to verbal commands, markedly confused, delirious, hyperreflexia, positive Babinski sign |

| IV (coma) | Usually absent | Appearance of delta waves, decreased amplitudes | Unconscious, decerebrate or decorticate response to pain present (stage IVA) or absent (stage IVB) |

EEG, Electroencephalogram.

From Fuhrman BP et al: Pediatric critical care, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2011, Saunders.

The physical examination in hepatic encephalopathy varies with the stage and may reveal the following abnormalities:

- Skin: Jaundice, palmar erythema, spider angiomata, ecchymosis, dilated superficial periumbilical veins (caput medusae) in patients with cirrhosis

- Eyes: Scleral icterus, Kayser-Fleischer rings (Wilson disease)

- Breath: Fetor hepaticus

- Chest: Gynecomastia in men with chronic liver disease

- Abdomen: Ascites, small nodular liver (cirrhosis), tender hepatomegaly (congestive hepatomegaly)

- Rectal examination: Hemorrhoids (portal hypertension), guaiac-positive stool (alcoholic gastritis, bleeding esophageal varices, peptic ulcer disease, bleeding hemorrhoids)

- Genitalia: Testicular atrophy in males with chronic liver disease

- Extremities: Pedal edema from hypoalbuminemia

- Neurologic: Flapping tremor (asterixis), obtundation, coma with or without decerebrate posturing

- Hepatic encephalopathy is thought to be caused mainly by accumulation of unmetabolized ammonia. The shunting of ammonia into the systemic circulation results in neuronal dysfunction leading to hepatic encephalopathy

- Precipitating factors in patients with underlying cirrhosis (upper gastrointestinal bleeding, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, analgesic and sedative drugs, sepsis, alkalosis, increased dietary protein)

- Acute fulminant viral hepatitis

- Drugs and toxins (e.g., isoniazid, acetaminophen, diclofenac and other NSAIDs, statins, methyldopa, loratadine, propylthiouracil, lisinopril, labetalol, halothane, carbon tetrachloride, erythromycin, nitrofurantoin, troglitazone, herbal products, flavocoxid)

- Reye syndrome

- Shock and/or sepsis

- Fatty liver of pregnancy

- Metastatic carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma

- Other: Autoimmune hepatitis, ischemic venoocclusive disease, sclerosing cholangitis, heat stroke, amebic abscesses