AUTHORS: Omar Karim, BS, and Manuel f Dasilva, MD

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) describes a family of small to medium vessel systemic vasculitides that shares many overlapping features, including clinical manifestations and therapies but also has distinct differences among each condition (granulomatosis with polyangiitis [GPA], microscopic polyangiitis [MPA], and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis [EGPA]). These vasculitides are characterized by necrotizing, pauci-immune small vessel vasculitis with GPA and without MPA granulomatous inflammation. Most patients present with both renal and pulmonary involvement, but the skin, nervous system, and gastrointestinal tract can also be affected. In a limited form of GPA, disease is generally confined to the upper respiratory tract and can be managed less aggressively.

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated vasculitis

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive vasculitis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

| ||||||||||||||||||||

6 to 12 cases per million per year in Western Europe and Japan, but statistics vary globally1

Infections (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus), silica exposure, hydrocarbon exposure, cigarette smoking, pesticides, medications (e.g., hydralazine, minocycline, propylthiouracil, levamisole-cocaine, allopurinol)

- Constitutional symptoms: Fever, fatigue, weight loss, myalgia, arthralgia.

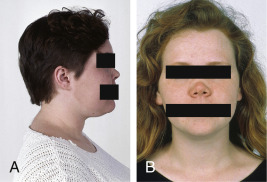

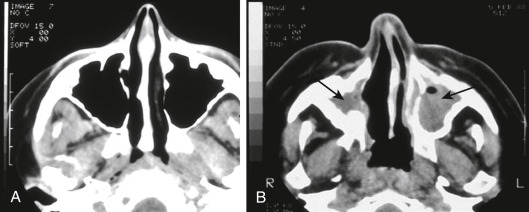

- Upper respiratory tract (URT): Chronic sinusitis, chronic otitis media, mastoiditis, nasal crusting, obstruction and epistaxis, nasal septal perforation, nasal lacrimal duct stenosis, saddle nose deformities (Fig. 1), tracheal and subglottic stenosis. Up to 90% of patients with GPA have one or more URT manifestations.

- Eyes: Conjunctivitis, ulcerative keratosis, episcleritis or scleritis, optic neuropathy, nasolacrimal duct obstruction, retinal vasculitis, uveitis, proptosis.

- Ears: Sensorineural and conductive hearing loss, otorrhea, and polychondritis.

- Mouth: Chronic ulcerative lesions of the oral mucosa, “mulberry” gingivitis, can be seen in GPA.

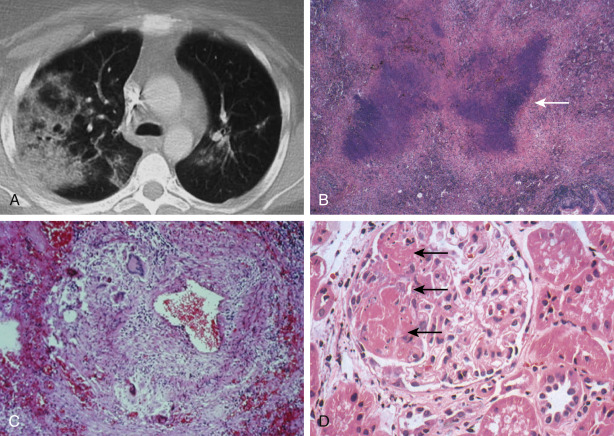

- Pulmonary: Dyspnea, hemoptysis, pleuritic chest pain. Imaging may show nodules, infiltrates, cavitary lesions, effusion, or alveolar hemorrhage.

- Gastrointestinal: Ischemic abdominal pain, peritonitis, bloody diarrhea, bowel ulceration or perforation, most commonly in MPA.

- Renal: Most affected organ in GPA and MPA. Elevated blood pressure, edema, decreased urine output. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (38% to 70%), microscopic hematuria with or without red cell casts, and proteinuria.

- Nervous system: Mononeuritis multiplex and peripheral neuropathies (15% to 50% in both), meningeal inflammation (pachymeningitis), headaches, and rarely central nervous system (CNS) involvement with seizures or strokes.

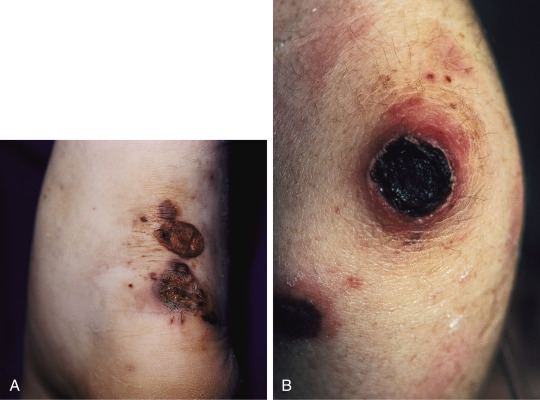

- Skin: Cutaneous nodules over extensor surfaces of joints, necrotizing skin lesions (Fig. E2), palpable purpura (30% to 46%), urticaria, livedo reticularis, and digital gangrene.

Figure 1 Saddle-nose deformity in a patient with Wegener granulomatosis.

From Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2009, Elsevier.

TABLE 1 Preliminary Criteria for the Classification of Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS)

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Definite Catastrophic APS | |||

| All four criteria | |||

| Probable Catastrophic APS | |||

| Criteria 2 through 4 and two organs, systems, or tissues involved | |||

| Criteria 1 through 3, except no confirmation 6 wk apart owing to early death of patient not tested before catastrophic episode | |||

| Criteria 1, 2, and 4 | |||

| Criteria 1, 3, and 4 and development of a third event more than 1 wk but less than 1 mo after the first, despite anticoagulation |

a Usually, clinical evidence of vessel occlusions, confirmed by imaging techniques when appropriate. Renal involvement is defined by a 50% rise in serum creatinine, severe systemic hypertension, proteinuria, or some combination of these.

b For histopathologic confirmation, significant evidence of thrombosis must be present, although vasculitis may coexist occasionally.

c If the patient has not been diagnosed previously with APS, laboratory confirmation requires that the presence of antiphospholipid antibody be detected on two or more occasions at least 6 wk apart (not necessarily at the time of the event), according to proposed preliminary criteria for the classification of APS.

From Asherson RA et al: Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines, Lupus 12:530-534, 2003.

TABLE 2 Clinical Findings in the ANCA-Associated Vasculitides9-36

| GPA | EGPA | MPA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Common. Includes fatigue, malaise, fevers, and weight loss. | Common. Weight loss, fatigue, fevers, myalgias and arthralgias. | Very common. Generally precedes renal disease by months. |

| Pulmonary | 70%-95% of patients with respiratory symptoms or chest imaging abnormalities. Tracheobronchial and endobronchial disease in 10%-50%. | Asthma essentially universal. Patchy, heterogenous radiographic infiltrates in >70%. | 10%-30% with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. |

| Renal | 50%-90% of patients. | 20%-50% of patients. | RPGN almost universal. |

| Upper airway | 70%-95% of patients. Destructive or ulcerating lesions are suggestive. | Sinusitis, polyposis, and/or rhinitis in ≥70% of patients. Generally not destructive. | 5%-30%, with sinus disease most common. |

| Musculoskeletal | Arthralgias, synovitis, and myalgias in up to 80%. | Arthralgias and myalgias in up to 50%. | Arthralgias and myalgias in at least 50% of patients. |

| Eyes | 25%-60% of patients. Vision-threatening disease including uveitis, ocular ulcers. | <5%. | 0%-30% of patients. May be clinically silent. |

| Cardiac | 5%-25% of patients. Conduction delays or other ECG abnormality, systolic or diastolic dysfunction, pericarditis, or coronary artery vasculitis. | 30%-50% of patients and a major cause of mortality. Conduction delays or other ECG abnormality, systolic or diastolic dysfunction, pericarditis, or coronary artery vasculitis. | 10%-20%. CHF and pericarditis have been described. |

| Gastrointestinal | <10% | 30%-50% of patients and a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Hemorrhage, abdominal pain, infarct or perforated viscus. | 35%-55% of patients. Findings similar to PAN. Pain, bleeding, and ischemia. Rare visceral aneurysms. |

| Dermatologic | Up to 60%. Palpable purpura, ulcers, nodules or vesicles. | 50%-70% purpura, nodules, papules, leukocytoclastic vasculitis with or without eosinophils. | 35%-60% of patients with purpura common. |

| Neurologic | Both central and peripheral nervous system involvement. | Mononeuritis multiplex in 50%-75%. CNS in 5%-40%. | Mononeuritis multiplex in 10%-50%. |

| Chest imaging | Abnormal in >80%. Alveolar, interstitial or mixed infiltrates, often with nodular and/or cavitary disease. | Infiltrates in >70%. Airways disease common (airway wall thickening, hyperinflation). | Infiltrates in 10%-30%. Pleural effusions in 5%-20%. |

| ANCA | ANCA positive >90% (PR3-ANCA 75%, MPO-ANCA 20%). | ANCA positive in 50% (PR3-ANCA 5%, MPO-ANCA 45%). | ANCA positive in 90% (PR3-ANCA 30%, MPO-ANCA 60%). |

ANCA, Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; CHF, congestive heart failure; CNS, central nervous system; ECG, electrocardiography; EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis; MPA, microscopic polyangiitis; MPO, myeloperoxidase; PAN, polyarteritis nodosa; PR3, proteinase 3; RPGN, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis.

From Broaddus VC et al: Murray & Nadel’s textbook of respiratory medicine, ed 7, Philadelphia 2022, Elsevier.

Painful, ulcerative, necrotic plaques on the ankle (A) and elbow (B) of a female patient with GPA.

From Paller AS, Mancini AJ: Hurwitz clinical pediatric dermatology: a textbook of skin disorders of childhood and adolescence, ed 5, Edinburgh, 2016, Elsevier.

The etiology of this complex immune-mediated disorder remains unclear and is likely multifactorial in nature. ANCAs play a major role in the pathogenesis. When PR3 and MPO are expressed on cell surfaces of neutrophils, they can cause endothelial damage as well as local tissue necrosis if activated in extravascular tissue. Other risk factors including genetic, environmental exposure to silica or certain strains of S. aureus have been proposed.