AUTHOR: Nicholas J. Lemme, MD

Vasculitis refers generically to inflammation occurring within the walls of blood vessels. Blood vessel inflammation can result in either perforation of affected vessels with hemorrhage into adjacent structures or thrombosis with subsequent ischemia and infarction of supplied tissues. Vasculitis can occur as a primary process or secondary to another connective tissue disease, infection, or drug exposure. The systemic vasculitides are a heterogeneous group of disorders (Table 1) characterized by blood vessel inflammation affecting vessels of varying size and location resulting in a wide range of clinical manifestations dictated largely by which vessels are affected (Fig. 1 and Fig. E2). Vasculitis is traditionally classified according to the size of the blood vessels predominantly affected (Table 2). Antineutrophilic cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) includes granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA); microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), including renal-limited vasculitis (RLV); and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). All are associated with ANCA and have similar features on renal histology (e.g., a focal necrotizing, and often crescentic, pauciimmune glomerulonephritis). Several of these are covered in individual topics, including topics on ANCA-associated vasculitis, giant cell arteritis (GCA), Takayasu arteritis, and Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). Severity varies between and within specific vasculitides from a relatively benign, self-limited process to severe, life-threatening multisystem organ involvement with significant morbidity and mortality.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 2 Names and Definitions of Small Vessel Vasculitides as Presented by the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference

| Name | Definition and Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Small-vessel vasculitis | Vasculitis predominantly affecting small vessels, defined as small intraparenchymal arteries, arterioles, capillaries, and venules. Medium-sized arteries and veins may be affected. | ||

| ANCA-associated vasculitis | Necrotizing vasculitis with few or no immune deposits predominantly affecting small vessels (i.e., capillaries, venules, arterioles, and small arteries), associated with MPO ANCA or PR3 ANCA. Not all patients have ANCA. Add a prefix indicating ANCA reactivity (e.g., MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, ANCA-negative). | ||

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis | Necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tract, and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small- to medium-sized vessels (e.g., capillaries, venules, arterioles, arteries, and veins). Necrotizing glomerulonephritis is common. | ||

| Microscopic polyangiitis | Necrotizing vasculitis with few or no immune deposits predominantly affecting small vessels (i.e., capillaries, venules, or arterioles). Necrotizing arteritis involving small- and medium-sized arteries may be present. Necrotizing glomerulonephritis is very common. Pulmonary capillaritis often occurs. Granulomatous inflammation is absent. | ||

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss syndrome) | Eosinophil-rich and necrotizing granulomatous inflammation often involving the respiratory tract, and necrotizing vasculitis predominantly affecting small- to medium-sized vessels, and associated with asthma and eosinophilia. ANCA is more frequent when glomerulonephritis is present. | ||

| Immune complex vasculitis | Vasculitis with moderate to marked vessel wall deposits of Ig and/or complement components predominantly affecting small vessels (i.e., capillaries, venules, arterioles, and small arteries). Glomerulonephritis is frequent. | ||

| Anti-glomerular basement membrane disease | Vasculitis affecting glomerular capillaries, pulmonary capillaries, or both, with GBM deposition of anti-GBM autoantibodies. Lung involvement causes pulmonary hemorrhage, and renal involvement causes glomerulonephritis with necrosis and crescents. | ||

| Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis | Vasculitis with cryoglobulin immune deposits affecting small vessels (predominantly capillaries, venules, or arterioles) and associated with serum cryoglobulins. Skin, glomeruli, and peripheral nerves are often involved. | ||

| IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura) | Vasculitis, with IgA1-dominant immune deposits, affecting small vessels (predominantly capillaries, venules, or arterioles). Often involves skin and GI tract, and frequently causes arthritis. Glomerulonephritis indistinguishable from IgA nephropathy may occur. | ||

| Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis (anti-C1q vasculitis) | Vasculitis accompanied by urticaria and hypocomplementemia affecting small vessels (i.e., capillaries, venules, or arterioles), and associated with anti-C1q antibodies. Glomerulonephritis, arthritis, obstructive pulmonary disease, and ocular inflammation are common. |

ANCA, Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; GBM, glomerular basement membrane; GI, gastrointestinal; MPO, myeloperoxidase; PR3, proteinase 3.

From Firestein GS et al: Firestein & Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2021, Elsevier.

TABLE 1 Comparing the Vasculitides

| Disease | Pathophysiology | Classic Features | Testing | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giant cell arteritis | Mononuclear cell infiltration and giant cell formation | Headache, scalp tenderness, visual disturbance | ESR, CRP biopsy | Prednisone and aspirin, may need tocilizumab or sarilumab |

| Takayasu arteritis | Mononuclear cell infiltration and giant cell formation | Visual disturbance, chest pain, abdominal pain, differences in extremity blood pressure and pulses | Angiography | Prednisone Surgical or angiographic intervention |

| Polyarteritis nodosa | Polymorphonuclear infiltration | Fever, hypertension, myalgias, abdominal pain, hematuria, CHF, GI bleeding, orchitis | ESR, CRP biopsy Angiography | Prednisone (mild disease) plus cyclophosphamide (moderate-severe disease) Antiviral therapy if concurrent hepatitis B or C Azathioprine or methotrexate for maintenance of remission |

| Kawasaki disease | Polymorphonuclear infiltration | 5-day fever, conjunctivitis, oral lesions, rash, red palms and soles, edema, cervical lymphadenopathy | ESR, CRP leukocytosis Thrombocytosis Echocardiography | Aspirin plus IV gamma globulin |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis) | Granuloma formation secondary to aggregating neutrophils | Upper and lower respiratory symptoms, renal insufficiency, skin lesions, visual disturbance | ESR, CRP c-ANCA/PR3 | Prednisone and methotrexate (mild disease) Cyclophosphamide or rituximab plus prednisone (moderate to severe disease) |

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss syndrome) | Eosinophilic infiltration Allergic granulomas | Allergic rhinitis, nasal polyps, asthma | Leukocytosis Eosinophilia ESR, CRP biopsy | Prednisone with or without cyclophosphamide, mepolizumab |

| Henoch-Schönlein purpura | IgA complex deposition | Palpable purpura, arthralgias, GI disturbances, glomerulonephritis | Leukocytosis Eosinophilia Ig A elevation, skin biopsy | Usually self-limited NSAIDs Prednisone if necessary Rituximab (refractory cases) |

| Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis | Cold precipitable monoclonal or polyclonal immunoglobulins | Palpable purpura, glomerulonephritis, myalgias, weakness, peripheral neuropathy | Low complement levels, hepatitis C Renal biopsy | Rituximab with or without prednisonePeg interferon plus ribavirin (HCV infection) |

| Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis | Neutrophilic infiltration Mononuclear and eosinophilic infiltration | Palpable purpura, macules, vesicles, bullae, urticaria | Skin biopsy | Prednisone Colchicine Dapsone |

| Behçet syndrome | Polymorphonuclear infiltration | Recurrent oral aphthous ulcers, genital ulcers, skin lesions, visual disturbance | ESR, CRP leukocytosis Oral mucosa autoantibodies | Topical corticosteroids Prednisone with azathioprine (end-organ disease) Colchicine (aphthous ulcer and arthritis) Apremilast Infliximab (refractory disease) |

c-ANCA, Cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; CHF, congestive heart failure; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GI, gastrointestinal; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IV, intravenous.

From Adams JG et al: Emergency medicine: clinical essentials, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2013, Elsevier.

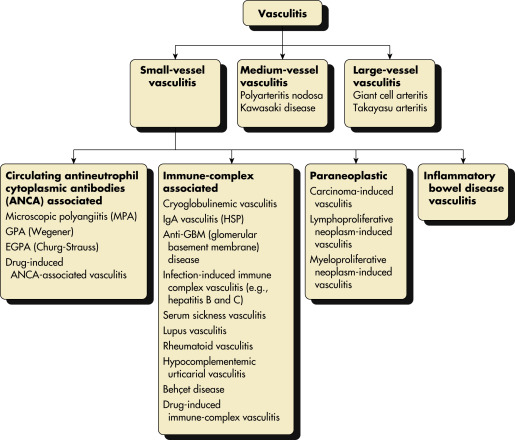

Figure 1 Major categories of noninfectious vasculitis.

Not included are vasculitides that are known to be caused by direct invasion of vessel walls by infectious pathogens, such as rickettsial vasculitis and neisserial vasculitis. EGPA, Eosinophilic granulomatous polyangiitis; GPA, granulomatous polyangiitis; HSP, Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

From Freehally J et al: Comprehensive clinical nephrology, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2019, Saunders.

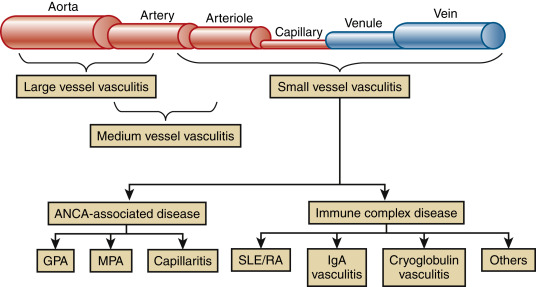

Figure E2 Relationship between vessel size and mechanism.

The small vessel vasculitides are diagrammed as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated disease and immune complex disease. ANCA, Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; GPA, granulomatosis with polyangiitis; IgA, immunoglobulin A; MPA, microscopic polyangiitis; SLE/RA, systemic lupus erythematosus/rheumatoid arthritis.

From Broaddus VC et al: Murray & Nadel’s textbook of respiratory medicine, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

- The epidemiology and demographics of the various vasculitides vary by the individual disease and, where applicable, are covered under the relevant vasculitis disease chapters.

- The most common form of systemic vasculitis in the U.S. is giant cell arteritis, with an approximate incidence of 170 cases/1 million per year in individuals older than 50 yr.

- ANCA-associated vasculitis is significantly less common with aggregate incidence estimated at ∼20 per million in the U.S.

- Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) has an annual incidence of 1/100,000 persons but has a higher incidence in patients with existing hepatitis B or C infections.

- Age distribution can demonstrate significant variability between the vasculitides as shown by the fact that GCA generally does not occur before age 50, whereas 90% of cases of HSP occur in the pediatric population, and 80% of patients with Kawasaki disease are under age 5.

- Although genetic factors clearly play a role in disease susceptibility, familial cases of vasculitis are rare.

- Clinical presentation often includes nonspecific constitutional symptoms including fever, malaise, headache, and weight loss.

- Signs and symptoms are generally dictated by the tropism of involved vessels.

- Skin manifestations of vasculitis include petechiae, palpable purpura (Fig. E3), subcutaneous nodules, livedo reticularis, ulcerations, and digital ischemia.

- Kidney involvement of medium-sized and large vessel vasculitis is often in the form of renovascular hypertension. Glomerulonephritis may be seen in small vessel vasculitis.

- Pulmonary small vessel involvement can cause alveolar hemorrhage, which can present with cough, dyspnea, and alveolar hemorrhage.

- Organ involvement in polyarteritis nodosa is summarized in Table 3.

- Mononeuritis multiplex is the characteristic finding of vasculitis affecting the vasa nervorum of the peripheral nervous system.

- GI involvement of the mesenteric vasculature can cause postprandial pain, bleeding, and perforation.

- Testicular pain or tenderness can be seen with hepatitis B infection in PAN.

- Cardiac involvement can include chest pain secondary to ischemic infarcts in the coronary arteries, pericarditis, cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmias.

- Arthritis, while nonspecific, can be present.

- Significant clinical variability exists between the various vasculitides, although overlapping symptoms may be seen.

TABLE 3 Organ Involvement in Polyarteritis Nodosa

| System | Comment | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Fever and weight loss (current and previous) | >90% |

| Musculoskeletal | Arthritis, arthralgia, myalgia, or weakness; when muscle is involved, it provides a useful site for biopsy | 24%-80% |

| Skin | Purpura, nodules, livedo reticularis, ulcers, bullous or vesicular eruptions, and segmental skin edema | 44%-50% |

| Cardiovascular | Cardiac ischemia, cardiomyopathy, hypertension | 35% |

| Ear, nose, and throat | No involvement; nasal crusting, sinusitis, and hearing loss suggest an alternative diagnosis such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis | None |

| Respiratory | Lung involvement not seen in PAN; abnormal respiratory findings suggest an alternative diagnosis | None |

| Abdominal | Pain is an early feature of mesenteric artery involvement; progressive involvement may cause bowel, liver, or splenic infarction, bowel perforation, or bleeding from a ruptured arterial aneurysm; less common presentations include appendicitis, pancreatitis, or cholecystitis as a result of ischemia or infarction; the presence of abdominal tenderness or peritonitis and blood loss on rectal examination should be assessed | 33%-36% |

| Renal | Vasculitis involving the renal arteries is present in many cases but does not commonly give rise to clinical features; it can present with renal impairment, renal infarcts, or rupture of renal arterial aneurysms; glomerular ischemia may result in mild proteinuria or hematuria, but red cell casts are absent because glomerular inflammation is not a feature; if evidence of glomerular inflammation exists, then an alternative diagnosis such as microscopic polyangiitis or granulomatosis with polyangiitis must be considered; hypertension is a manifestation of renal ischemia causing activation of the renin-angiotensin system | 11%-66% |

| Nervous system | Mononeuritis multiplex, with sensory symptoms preceding motor deficits; CNS involvement is a less frequent finding and can present with encephalopathy, seizures, and stroke | 55%-79% |

| Ocular | Visual impairment, retinal hemorrhage, and optic ischemia | Rare |

| Other | Breast or uterine involvement is rare; testicular pain from ischemic orchitis is a characteristic feature, albeit an uncommon presentation | Rare |

PAN, Polyarteritis nodosa.

From Firestein GS et al: Firestein & Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2021, Elsevier.