AUTHORS: Fahad Gul, MD and Pranav M. Patel, MD, FACC, FAHA, FSCAI

DefinitionTakayasu arteritis is a large-vessel vasculitis that primarily affects the aorta and its main branches. Chronic inflammation of involved vessels commonly leads to stenosis, occlusion, dilation, and aneurysms in the arterial wall.1

SynonymsPulseless disease

Aortitis syndrome

Aortic arch arteritis

Nonspecific aortoarteritis

Aortic arch syndrome

| ICD-10CM CODE | | M31.4 | Aortic arch syndrome [Takayasu] |

|

Epidemiology & DemographicsIn the U.S., the incidence is estimated around 0.4 to 2.6 per million people and about 4.7 to 8.0 cases per million outside of the U.S.2 The highest prevalence of Takayasu arteritis has been described in Japan, where all cases of Takayasu arteritis are registered by the government, and it has been estimated that 200 to 400 new cases occur every 3 yr.3 It has a female predominance, with female:male ratio around 8:1.2 Age of onset is between 10 and 40 yr with median age of onset of 20 yr.4

GeneticsThere is no established pattern of genetic inheritance; however, uncommonly the disease may be present among first-degree relatives.4 Half of the Japanese patients with Takayasu arteritis have the HLA-B52 allele.4 Other alleles associated with Takayasu arteritis include HLA-B39 and HLA-B67.4

Clinical Presentation & Physical FindingsTakayasu arteritis manifests with clinically nonspecific signs and symptoms of systemic inflammation, including general fatigue, weight loss, generalized arthralgias, myalgias, and low-/high-grade fever.5,6 These symptoms are usually subacute, which leads to delay in the diagnosis from months to years.2 Vascular symptoms are rare at presentation, and localized symptoms and signs vary depending on the location of the affected arteries.2,3

- Table E1 summarizes common symptoms and signs in Takayasu arteritis. “Red flags” for Takayasu arteritis are summarized in Table E2

- The occlusive stage of Takayasu arteritis may progress to stenosis or aneurysm of the aorta and its primary branches and may manifest as a variety of clinical signs and symptoms, such as2,3,5:

- Arm or leg claudication, weakness, and numbness

- Amaurosis fugax, diplopia, headache, orthostasis, vertigo, memory loss, or syncope

- Angina or myocardial infarction

- Vascular bruits of the carotid artery, subclavian artery, and aorta

- Discrepancy of blood pressures between the upper extremities, typically of ≥10 mm Hg

- Diminished or absent pulses, ischemic ulcerations, or gangrene in advanced disease

- Hypertension

- Retinopathy

- Aortic insufficiency as a result of aortic root dilation and aneurysm formation

- Weakness of the arterial walls may give rise to localized aneurysms/dissection

- Dyspnea or hemoptysis

- Skin lesions similar to erythema nodosum

- GI symptoms (abdominal pain, diarrhea, and GI bleed) secondary to mesenteric artery ischemia

Table E1 Common Symptoms and Signs (%) in Takayasu Arteritis

| Symptom/Sign | Study |

|---|

| Japan (n = 52) | India (n = 106) | China (n = 530) | Korea (n = 129) | U.S. (n = 60) | Mexico (n = 107) |

|---|

| Fatigue/constitutional | 27% | - | - | 34% | 43% | 78% |

| Weight loss | - | 9% | - | 11% | 20% | 22% |

| Musculoskeletal | 6% | 5% | - | - | 53% | 53% |

| Claudication | 13% | - | 25% | 21% | 90% | 29% |

| Headache | 31% | 44% | - | 60% | 42% | 57% |

| Visual changes | 6% | 12% | 10% | 20% | 30% | 8% |

| Syncope/dizziness | 40% | 26% | 14% | 36% | 35% | 13% |

| Palpitations | 23% | 19% | - | 23% | 10% | 43% |

| Dyspnea | 21% | 26% | 11% | 42% | - | 72% |

| Carotidynia | 21% | - | - | 2% | 32% | - |

| Hypertension | 33% | 77% | 60% | 40% | 35% | 72% |

| Bruit | - | 35% | 58% | 37% | 80% | 94% |

| Decreased pulses | 62% | - | 37% | 55% | 60% | 96% |

| Asymmetric blood pressure | - | - | - | - | 47% | - |

From Hochberg MC et al: Rheumatology, ed 5, St Louis, 2011, Mosby.

Table E2 “Red Flags” for Takayasu Arteritis (TA)

| In patients younger than 40 yr, the following may be indicative of TA: |

| Unexplained acute-phase response (raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate and/or C-reactive protein) |

| Carotidynia |

| Hypertension |

| Discrepant blood pressure between the arms (>10 mm Hg) |

| Absent or weak peripheral pulse or pulses |

| Limb claudication |

| Arterial bruit |

| Angina |

From Zipes DP: Braunwald’s heart disease, a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

Etiology & PathogenesisAs with most types of vasculitis, the cause of Takayasu arteritis is not known. Cell-mediated mechanisms (cytotoxic T cell, macrophage, natural killer cells, and others) and cytokine release (such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha [TNF-α], interleukin-6 [IL-6], and interferon-gamma [IFN-γ]) are thought to be important to the pathogenesis.6 Both pathways contribute to the induction and amplification of inflammation and tissue injury.6

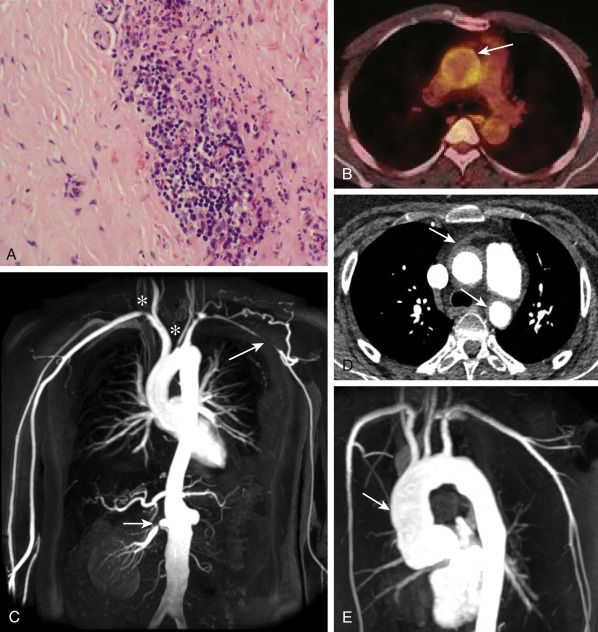

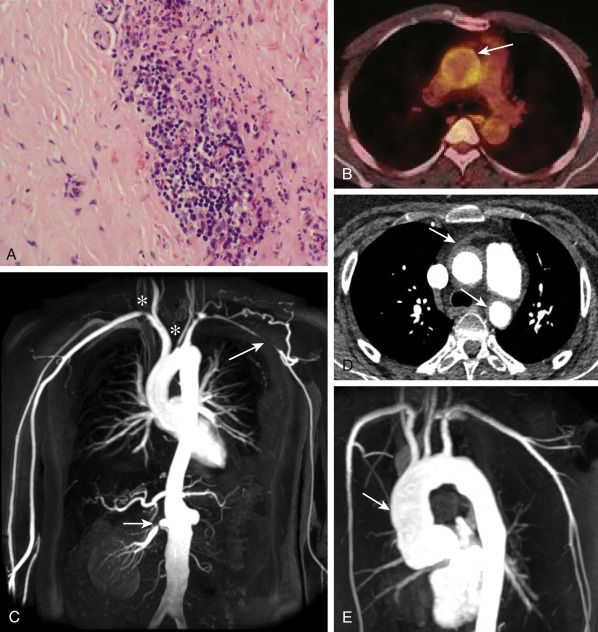

- Infiltration by inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, macrophages, and multinucleated giant cells) into the vasa vasorum and media of the large elastic arteries (Fig. E1) leads to production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), which cause destruction of elastic fibers in the arterial wall, neovascularization, and other inflammatory changes.7,8 An intermediate stage, driven in part by TNF-α, leads to mucopolysaccharide deposition and proliferation of fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells, causing intimal hypertrophy.8

- With chronic disease, inflammatory lesions progress to either thick fibrotic calcified narrowings or aneurysms if fibrosis is insufficient and the arterial wall is instead thinned and dilated.1

- Infection, in particular, tuberculosis, has been implicated in the pathogenesis, with several studies reporting an increased incidence of caseating granulomas in patients with Takayasu arteritis.9 Additional immunologic studies lend support to a pathogenic role of CD4 and CD8 T cells in this patient population.6

Figure E1 Takayasu arteritis.

A, Hematoxylin-eosin staining of a common carotid artery biopsy specimen obtained at surgery shows a focal mixed mononuclear cell inflammatory infiltrate with a multinucleated giant cell. B, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-PET-computed tomography scan demonstrating uptake in the aortic arch (arrow), consistent with active arteritis. C, Magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) demonstrating stenosis of the left subclavian artery with collateral formation (long arrow), proximal stenoses in the right subclavian and left common carotid arteries (stars), proximal stenosis in the right renal artery (short arrow), and an atrophic left kidney. D, Computed tomography angiogram demonstrating thickening of the wall of the ascending and descending aorta (arrows). E, MRA revealing severe dilation of the ascending aorta (arrow) requiring aortic valve replacement.

From Zipes DP: Braunwald’s heart disease, a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

Diagnostic criteria for Takayasu arteritis were established by the American College of Rheumatology in 1990.2 A diagnosis is made if at least three of the six criteria are present; this results in a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 98%.2 The criteria are:

- Age of disease onset <40 yr

- Claudication of the extremities

- Decreased brachial artery pulse

- Systolic blood pressure difference ≥10 mm Hg between left and right arms

- Bruit over one or both of the subclavian arteries or the abdominal aorta

- Abnormal arteriogram, not related to arteriosclerosis or fibromuscular dysplasia

Differential DiagnosisTable E3 describes pathologic characteristics of selected forms of vasculitis. Other causes of inflammatory arteritis must be excluded:

- Temporal arteritis (giant cell arteritis)

- Atherosclerosis

- Infectious aortitis

- Syphilis

- Tuberculosis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Buerger disease

- Behçet disease

- Marfan syndrome

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Cogan syndrome

- Kawasaki disease

- Spondyloarthropathies

- Fibromuscular dysplasia

- Relapsing polychondritis

Table E3 Pathologic Characteristics of Selected Forms of Vasculitis

| Takayasu Arteritis | Polyarteritis Nodosa | Wegener Granulomatosis | Churg-Strauss Syndrome | Henoch-Schönlein Purpura | Cutaneous Leukocytoclastic Angiitis |

|---|

| Vessels involved | Elastic (large) or muscle (medium-sized) arteries | Medium-sized and small muscle arteries | Small arteries and veins; sometimes medium-sized vessels | Small arteries and veins; sometimes medium-sized vessels | Capillaries, venules, arterioles | Capillaries, venules, arterioles |

| Organ involvement | Aorta, aortic arch and major branches, pulmonary arteries | Skin, peripheral nerve, gastrointestinal tract, other viscera | Upper respiratory tract, lungs, kidneys, skin, eyes | Upper respiratory tract, lungs, heart, peripheral nerves | Skin, joints, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys | Skin, joints |

| Type of vasculitis and inflammatory cells | Granulomatous with some giant cells; fibrosis in chronic stages | Necrotizing, with mixed cellular infiltrate | Necrotizing or granulomatous (or both); mixed cellular infiltrate plus occasional eosinophils | Necrotizing or granulomatous (or both); prominent eosinophils and other mixed infiltrate | Leukocytoclastic, with some lymphocytes and variable eosinophils; IgA deposits in affected tissues | Leukocytoclastic, with occasional eosinophils |

IgA, Immunoglobulin A.

From Goldman L, Schafer AI: Goldman’s Cecil medicine, ed 24, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders.

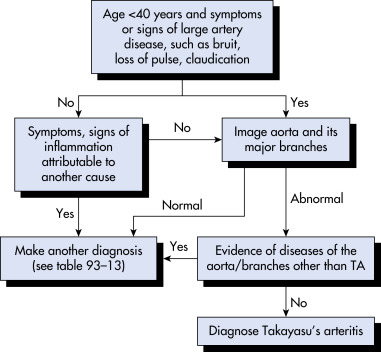

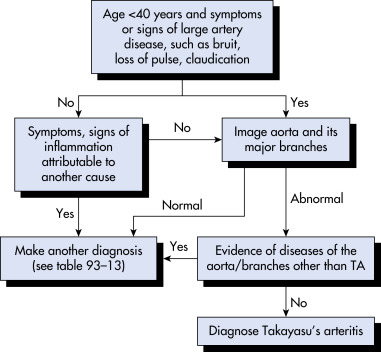

Workup (FIG. E2Any young patient with findings of absent pulses and loud bruits merits a workup for Takayasu arteritis. There are no diagnostic laboratory tests to diagnose Takayasu arteritis.2 Nonspecific inflammatory biomarkers, including C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), are useful markers for diagnosis, but normal values shouldn’t be used to rule out the disease.2 In most patients, the diagnosis is made by clinical findings and imaging of the arterial branches.2,7 Advanced imaging modalities, including contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and computed tomography angiography (CTA), allow for not only early diagnosis but also detailed assessment of vascular lesions.2,7 Three-dimensional reconstructions of the whole aorta and neck arteries using CTA are especially useful for surveying lesions.2,7 Ultrasound and fluorodeoxyglucose-PET are commonly used for diagnosis as well as in serial monitoring of disease activity.7 Catheter-based angiography is used to rule out ischemia and to measure core blood pressure when all four limbs arterial stenosis prevent accurate blood pressure measurement.7

Figure E2 Algorithm for the diagnosis of Takayasu’s arteritis (TA).

From Firestein GS et al: Firestein & Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2021, Elsevier.

Laboratory Tests

- ESR and serum CRP levels are usually but not always elevated.2,10

- A CBC may reveal a normal or elevated white blood cell count as well as anemia.10

- Immunologic studies may include elevated immunoglobulins (IgG and IgA) and complement components (C3 and C4).10

- Hypercoagulation and increase in platelet aggregation.10

Imaging Studies (TABLE E4

- Imaging of the entire aorta and major branch vessels using angiography, CTA, or MRA.7

- CTA can detect changes in the vessel wall and provide an accurate representation of luminal diameters.7

- MRA provides information on vessel lumen and wall thickening, cardiac morphology and function, and myocardial tissue characterization.7

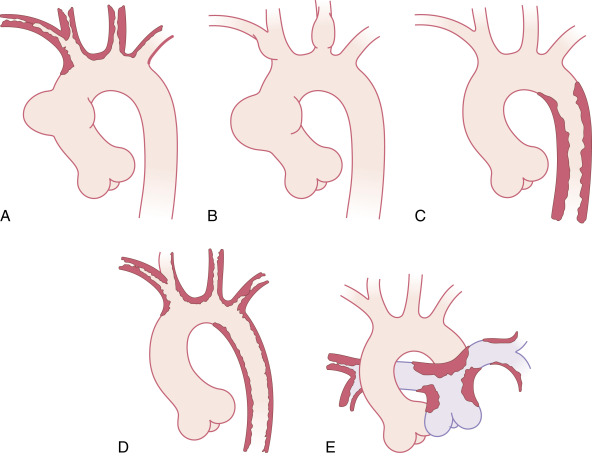

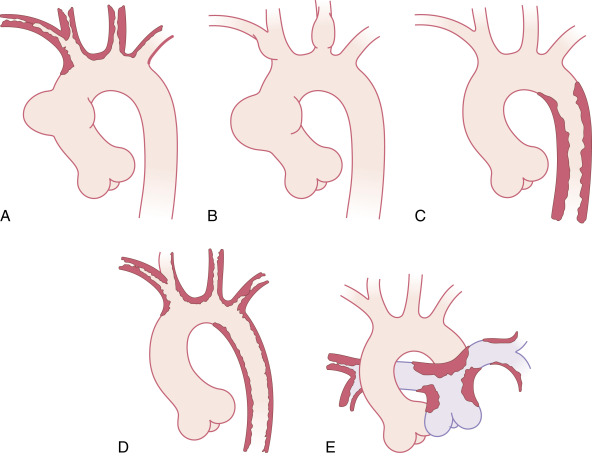

- Angiography can show the narrowing of the aorta and its branches, aneurysm formation, poststenotic dilation, and the development of any collateral circulation.3,7 Angiographic findings are classified into five major types (Fig. E3):

- Type I: Lesions that involve only branches of the aortic arch

- Type IIa: Lesions that involve the ascending aorta, the aortic arch, and its branches

- Type IIb: Lesions from IIa plus the thoracic descending aorta

- Type III: Lesions that involve the thoracic descending aorta, abdominal aorta, and/or renal arteries

- Type IV: Lesions that involve the abdominal aorta and/or renal arteries

- Type V: Lesions that involve the entire aorta and its branches

- Ultrasound: Carotid, thoracic, and abdominal ultrasound are useful adjunctive imaging studies to diagnose the occlusive disease that results from Takayasu arteritis. The addition of Doppler is helpful to assess blood flow and absent pulses.7

- PET using radioisotope fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET) as a marker for tissue with high glucose uptake has shown promising results in terms of specificity and sensitivity, especially in combination with CT (PET-CT) and MRI (PET-MR). The yield of using PET scans to measure disease activity is still under study.7

TABLE E4 Comparison of Imaging Techniques in Takayasu Arteritis

| Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|

| Conventional angiography | “Gold standard” image quality

Allows Cap measurement

Allows angioplasty at same time | Invasive

Radiation exposure

Does not visualize vessel wall thickness |

| Magnetic resonance angiography | Excellent image quality

Noninvasive

No ionizing radiation exposure

Visualizes vascular wall thickness | Image quality not “gold standard”

Cannot use in patients with pacemaker

Cap measurement not possible |

| Ultrasonography | Noninvasive

No ionizing radiation exposure

Can visualize vessel wall edema | Image quality not “gold standard”

Image quality affected by obesity

Operator dependent

Cap measurement not possible |

| CT angiography | Excellent image quality | Ionizing radiation exposure

Cap measurement not possible

Intravenous contrast agent required |

| Positron emission tomography | Can measure intensity of vascular inflammation | Ionizing radiation exposure

Vascular anatomy not well seen

Cap measurement not possible

Intravenous contrast agent required |

CAP, Central arterial blood pressure; CT, computed tomography.

From Firestein GS et al: Firestein & Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2021, Elsevier.

Figure E3 Takayasu disease.

A, Type I has stenoses in the aortic arch and its vessels. B, A variant form may have only local aneurysms. C, Type II has stenoses in the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta. D, Type III has features of both types I and II. E, Type IV has pulmonary artery involvement along with aortic disease.

From Boxt LM: Cardiac imaging, the requisites, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2016, Elsevier.

The most effective treatment is corticosteroids.5 However, relapses occur in a substantial number of patients during steroid tapering, and immunosuppressive agents are usually used concomitantly.5 Treatment of Takayasu arteritis consists of two parts: Induction and maintenance of remission and management of arterial complications.3

Acute General RxHigh-dose glucocorticoids are first-line therapy for suppressing systemic symptoms and stopping disease progression.1 Prednisone (1 mg/kg/day, up to a maximum daily dose of 60 to 80 mg) can be used for 3 mo or intravenous steroids can be administered initially.1,5,7

Attempts to taper prednisone can be made with resolution of constitutional symptoms, significant decline in the ESR and C-reactive protein levels, and in accordance with imaging studies.3,5

Because of steroids’ side effects and the high rate of relapse while tapering, it is recommended to use a glucocorticoid sparing agent at the time prednisone is prescribed. Commonly used second agents include3,5:

- Leflunomide

- Methotrexate

- Mycophenolate mofetil

- Azathioprine

- Tocilizumab

- Anti-TNF agents

- Cyclophosphamide

Chronic Rx

- Patients with Takayasu arteritis are monitored closely for signs of relapse and disease complications with clinical assessment, inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., ESR and CRP), and imaging.1,5 Multiple indexes exist for the assessment of disease activity, including the NIH criteria for active disease, the Disease Extent Index-Takayasu (DEI.Tak), and the Indian Takayasu Arteritis Score (ITAS).1

- Percutaneous angioplasty or bypass grafts should be considered for irreversible arterial stenoses with severe ischemia (cardiac or cerebral), severe hypertension in renal artery stenosis, or aneurysmal enlargement with risk of rupture.5 5-yr arterial complication rate after surgical or endovascular revascularization is around 40%.11 The likelihood of complications increases sevenfold when inflammation is present at the time of revascularization.11

- Aortic regurgitation may require valve replacement or repair by surgery, although the need to manipulate inflamed, friable tissue can lead to complications such as valvular detachment after replacement.12

- Treatment of hypertension in patients with Takayasu arteritis can be difficult, especially because there is usually concurrent glucocorticoid therapy and there is the potential for renovascular hypertension. Special monitoring should be employed when using ACE inhibitors due to the high frequency of renal artery stenosis in this population.1,5

Disposition

- Immunosuppressant therapy may achieve clinical remission.5

- Approximately 50% of patients will relapse during corticosteroid taper.1 Corticosteroid-sparing agents should be added to reduce the risk of relapse and minimize corticosteroid-associated adverse effects.1,5

- In the absence of major complications (MI, stroke, severe hypertension, heart failure, and aneurysm), 5-yr survival rates reach 80% to 90%. In the presence of major complications, 5-yr survival is 50% to 70%.7

- Death can occur suddenly from a ruptured aneurysm, a myocardial infarction, or a cerebrovascular accident.

Referral to specialist in high risk pregnancy. Pregnancy in Takayasu arteritis is considered a high risk pregnancy.1 The disease may cause uncontrolled hypertension, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, renal failure, and preeclampsia, which may lead to maternal and fetal comorbidity and mortality.1 Also, medical management with antihypertensive agents or immunosuppressants during pregnancy is challenging.

ReferralWhenever the diagnosis of vasculitis is suspected, a rheumatology consultation is appropriate.5 Vascular surgery and cardiology consultations are recommended for any evidence of carotid, peripheral, or coronary artery disease or if a large abdominal aneurysm is found.5

With long-term glucocorticoid use, consider measures to protect against bone loss. Bisphosphonates have been studied prospectively with corticosteroid use in this fashion; remember to ensure adequate dietary calcium and vitamin D intake as well.13

Comments

- No studies have proved that treatment results in regression of stenosis, although there are limited case reports describing the return of pulses with treatment.7

- Only one fifth of patients have a self-limited course. The majority show a progressive or relapsing remitting course that requires long-term immunosuppressive therapies.14

- Although short-term prognosis of the disease is favorable, long-term prognosis depends on the incidence of complications and the presence of progressive course. The presence of both major complications along with progressive course is associated with the worst prognosis. The prognosis and vascular complications of Takayasu arteritis are improving. Fatal or serious complications have diminished in the past decade.1,3