AUTHORS: Matthew Taylor, MD and Ross W. Hilliard, MD, FACP

Immunoglobulin A vasculitis (IgAV), formerly known as Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), is a systemic, small-vessel, IgA immune complex-mediated leukocytoclastic vasculitis characterized by a tetrad of palpable purpura, GI symptoms (colicky abdominal pain, GI bleed), renal disease, and arthritis/arthralgias.

Most common vasculitis seen in children and younger age groups; seen in White and Asian populations (primarily Indian and Pakistani ancestry in a study conducted in the West Midlands, UK, with suggested predominance in Japan and Korea)2,3; 3 to 4 times more commonly than in Black patients.

∼1.2 to 2:1 male:female ratio. Seen mostly from ages 3 to 12 with peak incidence between 4 and 6 yr. This disorder can be seen in older adolescents and young adults; however, 90% of cases are in patients <10 yr.2,4,5

In children, late autumn, winter, and early spring are the seasons with peak incidence. Cases in children are rare during the summer months. Seasonal variation is not seen in adults.2

There are no formally identified risk factors; however, rates of IgAV are higher in patients with familial Mediterranean fever and MEFV mutations.6 Viral precipitants have been theorized to trigger onset of the disease.

Recent studies have identified genetic susceptibility factors, but familial recurrence is rare. There appears to be a strong genetic predisposition with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class 2 region related to HLA-DRB1∗01 allele.7 There also may be protective genetic associations of HLA genes that may reduce the risk of acquiring the disease and explain ethnic differences. The ACE, IL∗, and HLA-B∗35 genes are associated with worse renal phenotype.

- Palpable purpura (Fig. E1) of dependent areas, especially lower extremities (palms and soles) and areas subjected to pressure, such as the beltline in adults or buttocks in toddlers. Facial involvement is rare.

- GI symptoms are seen in up to two thirds of patients. Common findings are abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cramping, hematochezia, and melena. Complications include GI bleeding (20% to 30%), bowel ischemia, intussusception (1% to 5%), and bowel perforation (<1%). Pancreatitis and acalculous cholecystitis are rare complications.

- Subcutaneous edema in dependent and periorbital areas.

- Arthralgias and arthritis in 60% to 85%. Typically, oligoarticular, affecting lower extremity and large joints. Periarticular swelling and tenderness also noted.

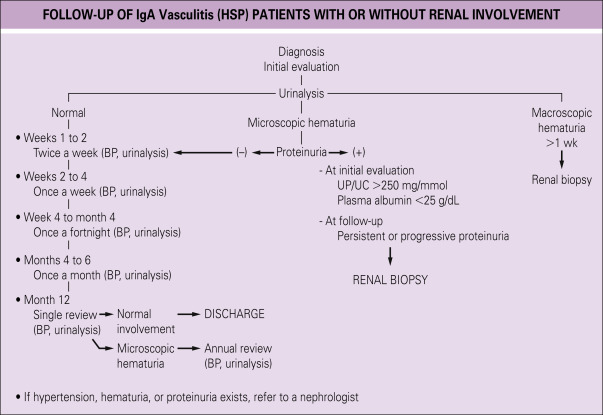

- Renal involvement is seen in as many as 80% of older children, usually within the first month of illness. Fewer than 5% progress to end-stage renal failure, which is a major cause of morbidity. Renal manifestations may range from isolated hematuria, proteinuria, or severe crescentic glomerulonephritis.

- Genitourinary involvement is seen between 2% and 38% of male children that can present with pain and edema of the scrotum, epididymitis, or orchitis that can mimic testicular torsion.8

- Central nervous system (CNS) involvement is rare, but can manifest as confusion, weakness, visual deficits, or impaired consciousness.

- Presumptive etiology is exposure to a trigger antigen that causes antibody formation.

- Antigen-antibody (immune) complex deposition, complement factor, and neutrophil infiltration then occurs in arteriole and capillary walls of skin, renal mesangium, and GI tract. IgA deposition is most common.

- Abnormal IgA1 glycosylation is a leading cause of the elevated serum galactose-deficient IgA1 levels seen in the disease. Notably, this is a trait shared with IgA nephropathy indicating a similar pathogenesis or, perhaps, two variants of the same disease.

- Antigen triggers include drugs, foods, immunizations, upper respiratory, or other viral illnesses. Group A β-hemolytic streptococcal infection is the most common precipitant in children, seen in up to one third of cases. Of childhood cases, 30% to 65% are preceded by an unspecified upper respiratory infection. Various precipitants have been described in case reports including parvovirus B19, Helicobacter pylori, intravesical bacille Calmette Guérin (BCG), and COVID-19.

- Emerging data suggests that COVID-19 precipitation of IgA vasculitis is caused by rapid IgA activation and subsequent immune complex deposition; occurring as early as two days after initial symptom onset.9

- Development of IgA vasculitis may be associated with exposure to medications, including antibiotics, antitumor necrosis factors, or chemotherapeutic agents or vaccines.1

- All vaccine subtypes have been identified as a potential precipitant of drug-induced IgA vasculitis. It is hypothesized that vaccine-mediated immune responses mimic the disease-mediated immune responses that would otherwise trigger IgA vasculitis.10