AUTHORS: Helen Zhang, BS and Manuel F. DaSilva, MD

Hyperuricemia is defined as high blood levels of uric acid based on physicochemical criteria. A statistical definition is inappropriate, as it would require certainty regarding the pathogenic cutoff or the plasma level above which monosodium urate (MSU) crystallizes. Plasma MSU is typically defined as 6.8 mg/dl but may differ depending on temperature and location in the body.1 Serum uric acid >7.0 mg/dl in males or >6.0 mg/dl in females is generally indicative of hyperuricemia.2 Some persons who are not hyperuricemic by this definition will have levels of uric acid that exceed the limit of solubility of uric acid in tissue. Age is an important risk factor in the increasing incidence of hyperuricemia and gout. Women become hyperuricemic at an older age than men due to the uricosuric effect of estrogen.3 Most people with hyperuricemia are asymptomatic and will remain so; however, 20% of those with serum uric acid >9 mg/dl will develop gout in 5 yr.4 Hyperuricemia is strongly associated with gout, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease but has not been proven to cause any of these conditions.

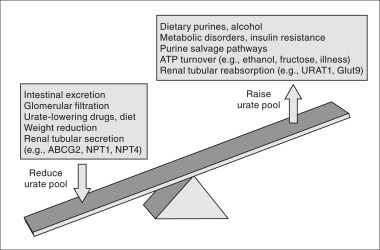

Factors associated with urate variation are summarized in Table E1. Overproduction of uric acid accounts for a minority of cases of hyperuricemia. Most cases are a result of decreased renal clearance of uric acid and high dietary purine consumption. Fig. E1 describes factors affecting urate balance. Table E2 describes classification of hyperuricemia and gout.

Figure E1 Factors affecting urate balance.

The systemic urate pool and the likelihood of gout are determined by the dynamic balance among dietary purines, endogenous synthesis and recycling, and disposal by the kidney and gut. ATP, Adenosine triphosphate.

From Hochberg MC et al: Rheumatology, ed 5, St Louis, 2011, Mosby.

TABLE E1 Factors Associated With Urate Variation

| Genetic Factors | Dietary Influences | Clinical Associations |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex Common variants associated with hyperuricemia (replicated) Rare monogenic causes | Associated with increased urate | Older age Postmenopause in women Medical comorbidities

|

FJHN, Familial juvenile hyperuricemic nephropathy; HPRT, hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase; MCKD, medullary cystic kidney disease; PRPP, 5-phosphoribosyl 1-pyrophosphate.

From Hochberg MC: Rheumatology, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

TABLE E2 Classification of Hyperuricemia and Gout

| Impaired Uric Acid Excretion | |||

| Primary gout with decreased uric acid clearance | |||

| Secondary gout | |||

| Clinical conditions | |||

| Reduced glomerular filtration rate | |||

| Hypertension | |||

| Obesity | |||

| Systemic acidosis | |||

| Familial juvenile hyperuricemic nephropathy | |||

| Medullary cystic kidney disease | |||

| Lead nephropathy | |||

| Drugs | |||

| Diuretics | |||

| Ethanol | |||

| Low-dose salicylates (0.3-3.0 g/day) | |||

| Cyclosporine | |||

| Tacrolimus | |||

| Levodopa | |||

| Excessive urate production | |||

| Primary metabolic disorders | |||

| HPRT deficiency | |||

| PRPP synthetase overactivity | |||

| Glucose-6-phosphatase deficiency | |||

| Fructose-1-phosphate aldolase deficiency | |||

| Secondary causes | |||

| Clinical conditions | |||

| Myelo- and lymphoproliferative disorders | |||

| Obesity | |||

| Psoriasis | |||

| Glycogenoses III, V, VII | |||

| Drugs and dietary components | |||

| Nicotinic acid | |||

| Pancreatic extract | |||

| Cytotoxic drugs | |||

| Red meat, organ meat, shellfish | |||

| Alcoholic beverages (especially beer) | |||

| Fructose |

HPRT, Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase; PRPP, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate.

From Goldman L, Schafer AI: Goldman’s Cecil medicine, ed 24, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders.