AUTHORS: Lisa Bird, MD and Nima R. Patel, MD, MS

An ectopic pregnancy (EP) occurs when a fertilized ovum implants outside the endometrial cavity.1

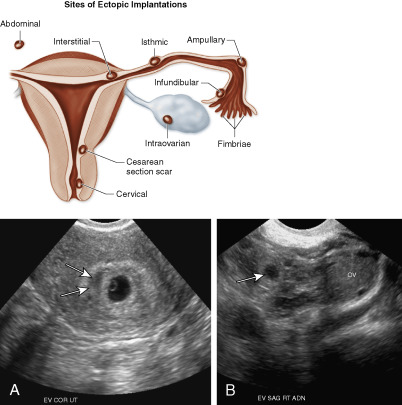

Interstitial (cornual) pregnancy (1% to 2%)

Abdominal pregnancy (0.03% to 1%)

Cesarean scar pregnancy (1% to 3%, 6% of all EP in women with prior cesarean)

Heterotopic pregnancy (1/4000 to 1/30,000, but 1/100 after in vitro fertilization)1

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

- 1% to 2% of pregnancies; represents 3% of pregnancy-related deaths.2

- Most common cause of death in first trimester.

- African American patients have a 1.5-fold higher risk.

Accounts for up to 18% of women presenting to the emergency room with vaginal bleeding or abdominal pain.1 Currently over 100,000 reported cases/yr.

Prior ectopic, altered tubal anatomy, prior pelvic infection (pelvic inflammatory disease, tuboovarian abscess, salpingitis), prior sterilization procedure, prior tuboplasty or tubal surgery, prior cesarean delivery, current intrauterine device use, assisted reproductive techniques, infertility, cigarette use, age >35, multiple lifetime sexual partners, diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure in utero. Half of patients with EP have no risk factors.1

- The classic presentation of EP includes the triad of abnormal vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, and an adnexal mass

- Abdominal tenderness: 95%

- Adnexal tenderness: 87% to 99%

- Amenorrhea or abnormal vaginal bleeding: 75%

- Peritoneal signs: 71% to 76%

- Adnexal mass: 33% to 53%

- Enlarged uterus: 6% to 30%

- Shoulder pain: 10%

- Tissue passage: 6% to 7%

- Shock: 2% to 17%