AUTHOR: Corey Elam Goldsmith, MD, FAAN

DefinitionOptic neuritis is an inflammation of the optic nerve(s) resulting in impaired visual function and often retroorbital pain worse with eye movements.

SynonymsOptic papillitis

Retrobulbar neuritis

| ICD-10CM CODES | | H46.8 | Other optic neuritis | | H46.9 | Unspecified optic neuritis |

|

Epidemiology & DemographicsIncidence (In U.S.)1 to 5/100,000 person(s) per year; rates vary according to incidence of multiple sclerosis (MS). Optic neuritis affects 1% to 5% of patients with neurosarcoidosis.

Prevalence (In U.S.)Common in patients with MS (70%), neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD; 63%), and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody disease (MOGAD; at least 55%)

Predominant SexFemale:male ratio: 1.8:1

Peak Incidence20 yr to 49 yr, mean 30 yr

GeneticsUnknown. If due to MS, it is more common in patients with certain human lymphocyte antigen (HLA) blood types and in monozygotic twins of affected siblings.

Physical Findings & Clinical Presentation

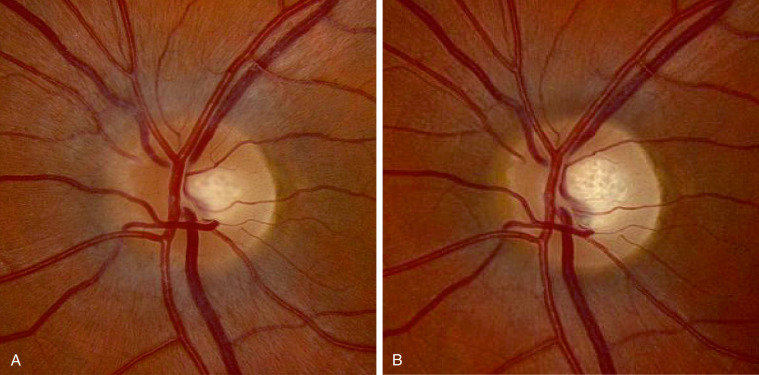

- Presentation with acute (days) or subacute (weeks) vision loss, often accompanied by retroorbital pain that worsens with eye movements. Visual field defects commonly are present; they can be either diffuse or discrete scotomas and are nonspecific. Fundus examination shows mild disc edema in approximately one third of affected eyes, which is typically less prominent than the disc swelling associated with papilledema (Fig. E1). In the majority of patients, the fundus appearance is normal.

- Marcus Gunn pupil (relative afferent pupillary defect [RAPD]): Consensual response is normal; however, when the flashlight is swung from the unaffected eye to the affected eye, the affected eye’s pupil paradoxically dilates in response to direct light.

- Decreased visual acuity.

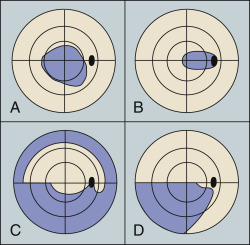

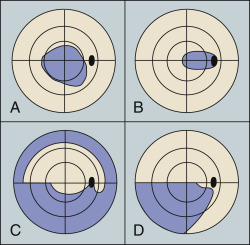

- Unilateral (or bilateral with some diseases) visual field abnormalities-often a central scotoma (Fig. E2) or diffuse (in MS), or altitudinal (in NMOSD).

- Color desaturation; red is most often affected.

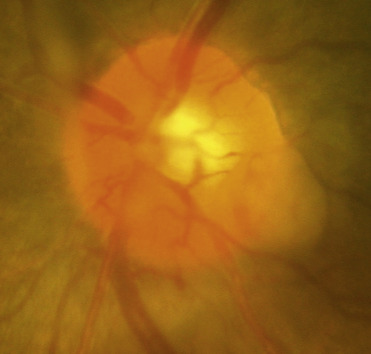

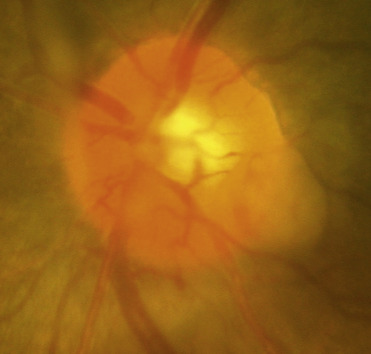

- Normal fundus examination in 66% of cases; disc edema is noted in 33% (more frequent and severe when associated with MOGAD, infectious, or granulomatous causes). Other abnormalities can include uveitis, periphlebitis, episcleritis, and retinitis. In neurosarcoidosis, the optic nerve head may exhibit a lumpy appearance suggestive of granulomatous infiltration, and there may be associated vitreitis (Fig. E3).

- May have movement or light induced phosphenes (flashes of light lasting 1 to 2 sec).

- Uhthoff phenomenon (benign exercise- or heat-induced deterioration of vision due to elevated core body temperature, lasting less than 24 h) is seen in some. Vision may also worsen in bright sunlight.

- Over time, the optic disc may atrophy and become pale.

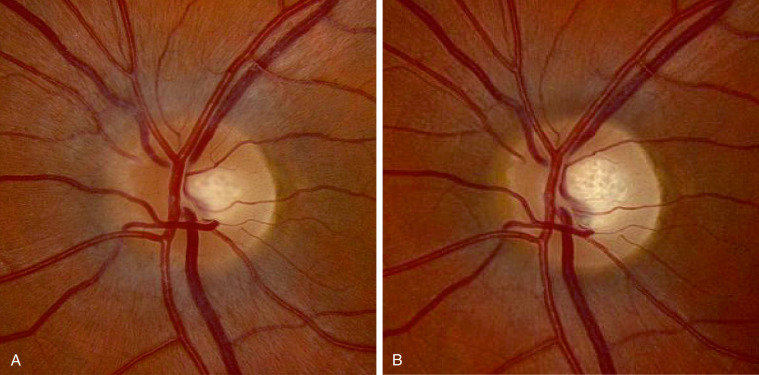

Figure E1 (A) Fundus Photograph of the Left Eye in a Patient with Acute Left Optic NeuritisNote Mild Nerve Fiber Layer Edema, Greatest at the Nasal Portion of the Disc, Without Hemorrhages or Cotton-Wool Spots. (B) Fundus Photograph of the Left Eye from the Same Patient Taken 3 Mo after Initial Presentation. Note Resolution of Edema and Presence of Mild Temporal Pallor.

From Jankovic J et al: Bradley and Daroff’s neurology in clinical practice, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

Figure E2 Visual field defects in optic neuritis.

(A) Central scotoma. (B) Centrocecal scotoma. (C) Nerve fiber bundle. (D) Altitudinal.

From Kanski JJ, Bowling B: Clinical ophthalmology: a systematic approach, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.

Figure E3 Sarcoid granuloma of the optic nerve head with overlying vitreous haze.

From Bowling B: Kanski’s clinical ophthalmology, a systemic approach, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2016, Elsevier.

EtiologyAn inflammatory response associated with infectious, paraneoplastic, or autoimmune disease (such as collagen vascular disease, granulomatous disease, MS, NMOSD, and MOGAD).

Diagnosis is clinically established in a young patient with acute onset of monocular vision loss, associated with retroorbital pain with eye movements and presence of RAPD lasting more than 24 h. Absence of other orbital or ocular pathology is based on clinical examination.

Differential Diagnosis

- Inflammatory: MS, NMOSD, MOGAD, sarcoidosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, lupus, Sjögren syndrome, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, paraneoplastic (CRMP-5, CV-2), autoimmune optic neuropathy, autoimmune glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) astrocytopathy

- Infectious: Neurosyphilis, tuberculosis (TB), Lyme disease, HIV, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, varicella-zoster virus, Epstein-Barr virus, West Nile virus, dengue fever, Bartonella henselae, Rickettsia spp., Toxocara spp., Q fever, histoplasmosis, toxoplasmosis, helminths, periorbital infections

- Ischemic: Anterior and posterior ischemic optic neuropathies, diabetic papillopathy, branch or central retinal artery or vein occlusion

- Drugs and toxins: Arsenic, methanol, ethambutol, cyclosporine, etc.

- Mitochondrial: Leber hereditary optic neuropathy, other mitochondrial

WorkupThorough neurologic examination with dilated ophthalmoscopy

Laboratory TestsAcute optic neuritis is a clinical diagnosis based on presentation with classical features: Acute, painful, unilateral loss of vision associated with RAPD in a young person with no other apparent causes (such as trauma). In atypical cases, additional studies may be considered.

- CBC, antinuclear antibody (ANA), ACE, cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (c-ANCA), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- Consider HIV Ab, Lyme titer, rapid plasma reagin (RPR), Quantiferon TB gold, other autoimmune or infectious causes

- CSF studies: Can demonstrate pleocytosis, CSF-specific oligoclonal bands and IgG synthesis (more common with MS), GFAP-IgG (in autoimmune GFAP astrocytopathy)

- Bilateral or recurrent optic neuritis: Serum antiaquaporin-4 (AQP4) IgG (in NMOSD), serum and CSF MOG-IgG (in MOGAD), serum CRMP-5-IgG (in paraneoplastic disease)

Imaging Studies

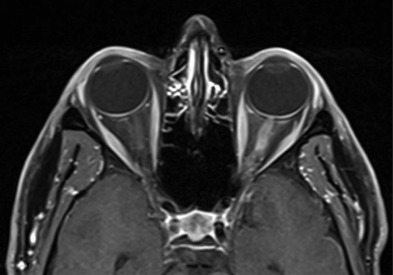

- Contrast-enhanced MRI of the orbits (Fig. E4) with fat suppression and thin sections is highly sensitive in detecting acute or subacute optic neuritis, seen as enhancement of the optic nerve(s) (Fig. E5).

- Longitudinally extensive retrobulbar optic nerve involvement is common with NMOSD and MOGAD.

- Contrast-enhanced MRI of the brain should simultaneously be performed to assess for possible MS. Contrast-enhanced MRI of the cervical and thoracic spine should also be considered to assess for possible demyelinating disease.

- Visual evoked potentials: Tests the axonal transmission along the optic nerve. Prolonged P100 latency of the optic nerve(s) confirms the presence of optic neuropathy. Useful in confirming equivocal cases of optic neuritis.

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT): Can show peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickening in acute optic neuritis, and peripapillary RNFL and macular thinning in chronic or recurrent optic neuritis. Useful to follow optic nerve atrophy objectively and longitudinally.

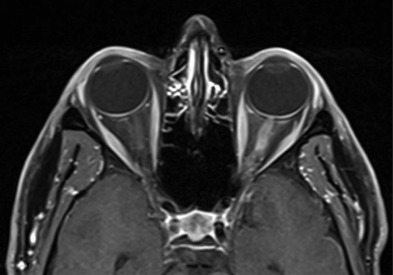

Figure E4 Axial T1-Weighted Postgadolinium Magnetic Resonance Imaging with Fat Saturation in a Patient with Left Optic Neuritis

Note enhancement of the left optic nerve consistent with acute inflammation.

From Jankovic J et al: Bradley and Daroff’s neurology in clinical practice, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

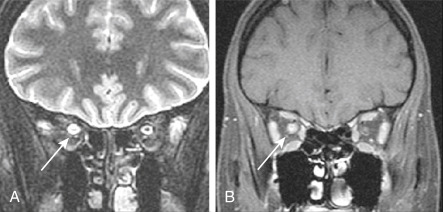

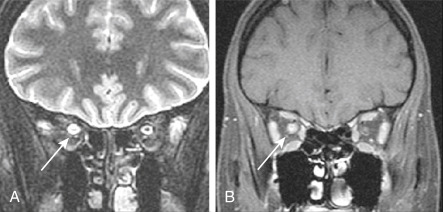

Figure E5 Right optic neuritis.

Coronal fat-suppressed T2-weighted fast spin-echo (A) and fat-suppressed contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images. There is hyperintensity of the right optic nerve, with diffuse enhancement (arrows) (B).

From Grant LA: Grainger & Allison’s diagnostic radiology essentials, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.