General Rx

- There are only four FDA-approved SLE medications: Aspirin, corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine (1955), and belimumab (2011).

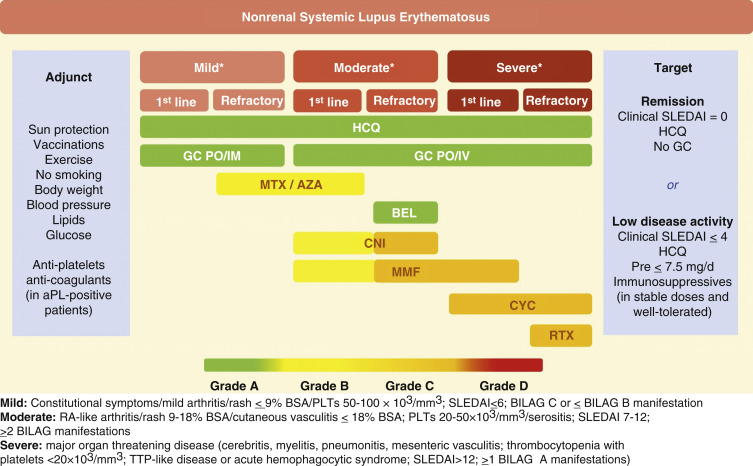

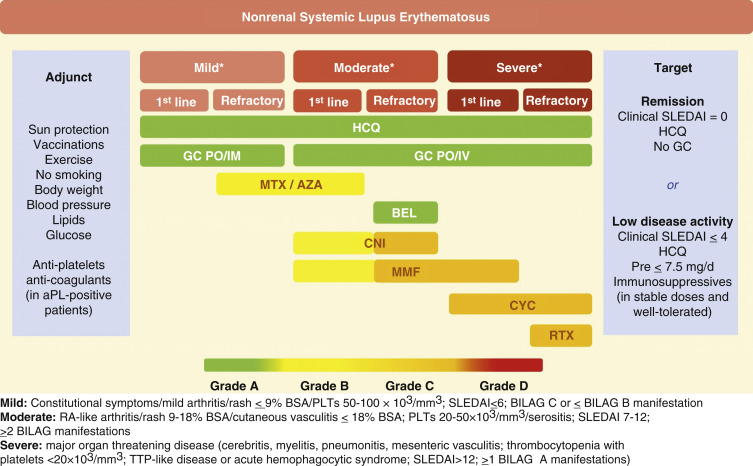

- Treatment should be targeted toward the involved organ(s). Recommended drugs for the treatment of SLE according to stratification of disease severity are described in Fig. 4. Indications for immunosuppressive therapy in SLE are summarized in Table 6.

- Limited and defined courses of corticosteroids are useful for a variety of SLE symptoms. Steroid therapy should be restricted to acute or subacute control of symptoms, due to the increased cardiovascular risk and increased organ damage associated with chronic steroid use. Recommended drug monitoring in SLE is summarized in Table 7.

- Consider checking G6PD in certain ethnic groups more predisposed to antimalarial- induced hemolytic anemia.

- Hydroxychloroquine has best evidence for reducing flares, organ damage, lipids, thrombosis; improving survival; augmenting action of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) in LN; and preventing seizures. Currently recommend not to exceed an oral dose of 5 mg/kg/day to decrease risk of retinal toxicity.1

- Methotrexate and azathioprine are used as steroid-sparing agents. Indications include cutaneous and joint involvement.1

- Joint pain and mild serositis are generally well controlled with NSAIDs or low-dose corticosteroids. Hydroxychloroquine and methotrexate are also effective for arthritis. Belimumab does well for joint and cutaneous manifestations. Leflunomide and rituximab may be considered for refractory arthritis. Treatment approach for musculoskeletal features of SLE is summarized in Table 8.

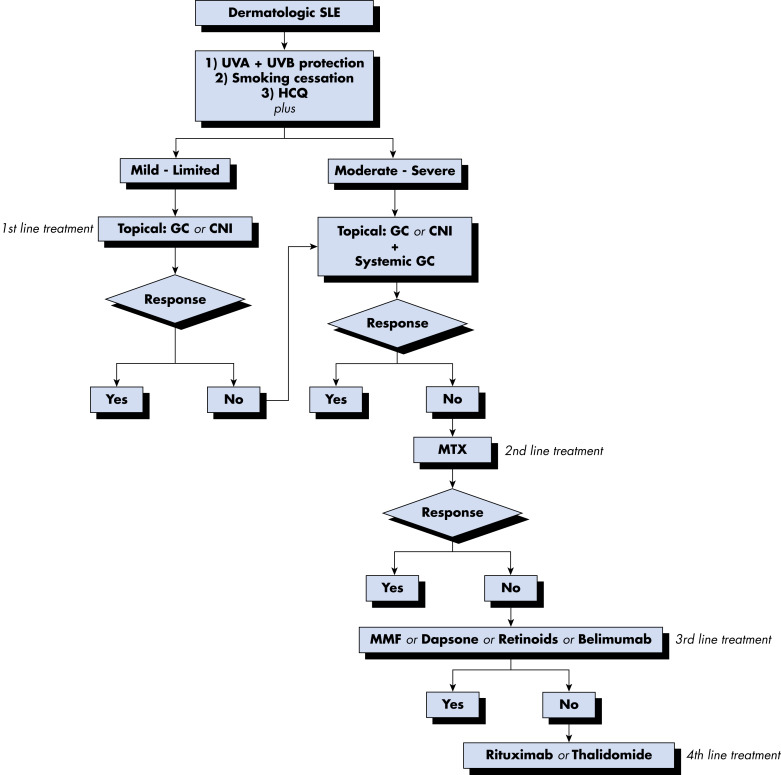

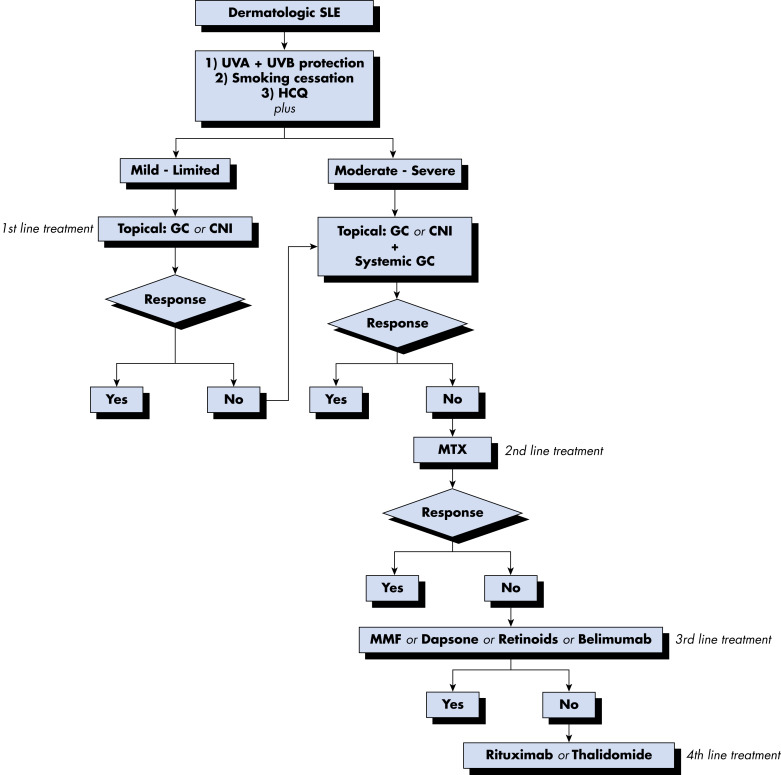

- Cutaneous manifestations:

- Topical or intradermal corticosteroids are helpful for individual discoid lesions, especially in the scalp.

- Hydroxychloroquine alone or in combination with quinacrine and/or chloroquine can be considered for refractory skin disease.

- Refractory cases may be treated with belimumab, MMF, dapsone, or combination treatment.1,8

- Fig. E5 and Table E9 summarize general management of cutaneous lesions in SLE.

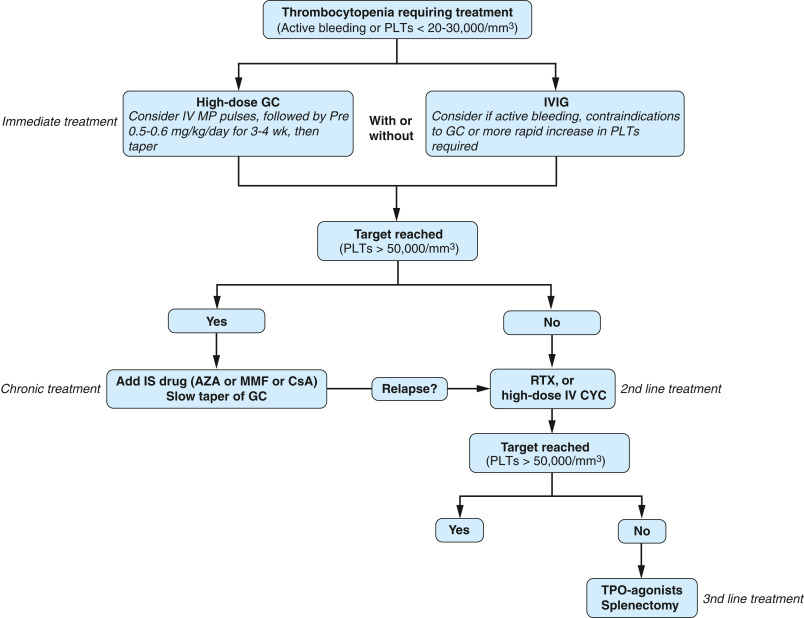

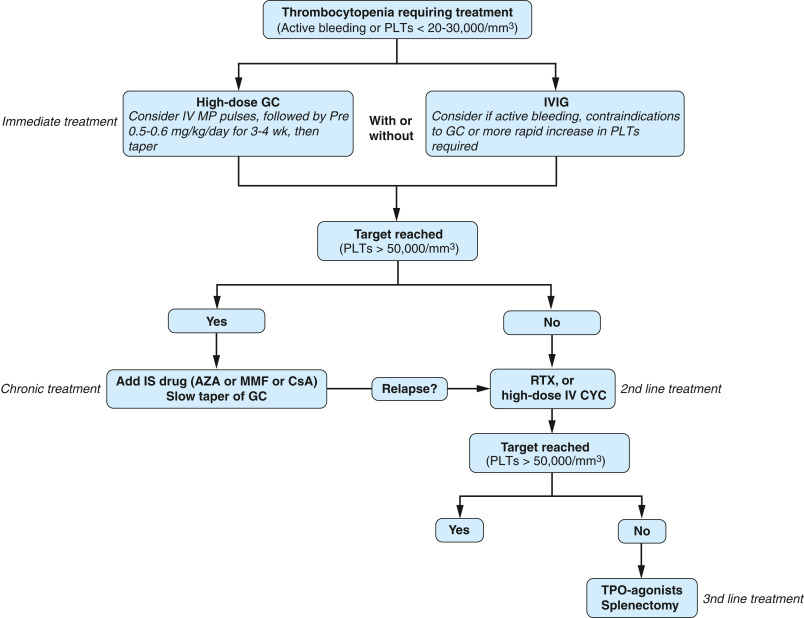

- Hematologic manifestations:

- Corticosteroids are first-line therapy. Table E10 summarizes the treatment and main hematologic features of SLE.

TABLE E9 General Management of Cutaneous Lesions in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

| Acute | SCLE | DLE |

|---|

| Nonpharmacologic Measures |

| Photoprotection | Photoprotection | Photoprotection |

| Avoidance of photosensitizing drugs | Avoidance of photosensitizing drugs | Avoidance of photosensitizing drugs |

| Smoking cessation | Smoking cessation | Smoking cessation |

| Topical Treatment |

| Topical calcineurin inhibitors | Topical glucocorticoids | Topical corticosteroids |

| Topical calcineurin inhibitors | Topical calcineurin inhibitors |

| Intralesional glucocorticoids | Intralesional glucocorticoids |

| | R-salbutamol |

| Systemic Treatment |

| First line | Antimalarials | Antimalarials | Antimalarials |

| Glucocorticoids | | Glucocorticoids |

| Second line | | Systemic retinoids | MTX |

| | Systemic retinoids |

| | Antimalarial combination |

| Refractory Cases |

| According to systemic involvement | Thalidomide | Dapsone |

| RTX | Leflunomide | Thalidomide |

| Belimumab | MMF | Belimumab |

| IVIGs | RTX |

| RTX | Lenalidomide |

| Belimumab | |

| Therapies Under Investigation |

| Abatacept | Abatacept | Abatacept |

| Sifalimumab | Sifalimumab |

| Apremilast | Apremilast |

DLE, Discoid lupus erythematosus; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate; RTX, rituximab; SCLE, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

From Hochberg MC: Rheumatology, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

Figure E5 Suggested Algorithm for the Management of Cutaneous Manifestations in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

CNI, Calcineurin inhibitors; GC, glucocorticoids; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate; UVA/UVB, ultraviolet A/B.

From Firestein GS et al: Firestein & Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2021, Elsevier.

TABLE 8 Treatment Approach for Musculoskeletal Features of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

| First-Line Therapy | Second-Line Therapy | Third-Line Therapy | Experimental Therapy |

|---|

| Arthritis | HCQ or CQ | MTX | Belimumab | Abatacept |

| Low doses of glucocorticoids | Leflunomide | RTX | Sifalimumab |

| | Anti-TNF | |

| AVN | Avoid high doses of corticosteroid | Antiaggregation in aPL positivity | Core decompression | |

| | Percutaneous drilling | |

| | Arthroplasty | |

| Myositis | High-dose corticosteroid | MTX | IVIG | |

| Azathioprine | RTX | |

aPL, Antiphospholipid; AVN, avascular necrosis; CQ, chloroquine; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; MTX, methotrexate; RTX, rituximab; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

From Hochberg MC: Rheumatology, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

TABLE 7 Recommended Drug Monitoring in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

| Drug | Dosage | Dose Adjustment | Toxicities Requiring Monitoring | Baseline Evaluation | Laboratory Monitoring |

|---|

| Azathioprine | 50-200 mg/day in 1-3 doses with food | ↓25% if eGFR 10-30 ml/min; ↓ 50% if eGFR <10 ml/min | Myelosuppression, hepatotoxicity, lymphoproliferative diseases | CBC, platelets, Cr, AST or ALT | CBC and platelets every 2 wk, with changes in dosage; during monitoring every 1-3 mo |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 1-3 g/day in 2 divided doses with food | Maximum 1 g/day if eGFR <25 ml/min | Myelosuppression, hematotoxicity, infection | CBC, platelet, Cr, AST or ALT | CBCs and platelets every 1-2 wk with changes in dosage; during monitoring every 1-3 mo |

| Cyclophosphamide | 50-150 mg/day in a single dose with breakfast. Increase fluid intake (at least 3 L water/day), empty bladder before bedtime | ↓25% if eGFR 25-50 ml/min; ↓ 30%-50% if eGFR <25 ml/min; ↓ 25% if serum Bil 3.1-5 mg/dl or transaminases >3 times ULN | Myelosuppression, hemorrhagic cystitis, myeloproliferative disease, malignancies | CBC, platelet, Cr, AST or ALT, urinalysis | CBC with differential every 1-2 wk, with changes in dosage and then every 1-3 mo; keep WBC >4000/mm3 with dose adjustment; urinalysis for hematuria, AST or ALT every 3 mo; urinalysis for hematuria every 6-12 mo following cessation |

| Methotrexate | 7.5-25 mg/wk in 1-3 doses with food or milk/water | ↓50% if eGFR 10-50 ml/min; avoid use if eGFR <10 ml/min; avoid use in hepatic dysfunction (serum Bil 3.1-5 mg/dl or transaminases >3 times ULN) | Myelosuppression, hepatic fibrosis, pneumonitis | Chest radiograph, hepatitis B/C serology in high-risk patients, AST or ALT, Alb, ALP, Cr | CBC with platelet, AST, Alb, Cr every 1-3 mo |

| Cyclosporin A | 100-400 mg/day in 2 doses at the same time every day with meal or between meals | Avoid in impaired renal function | Renal insufficiency, anemia, hypertension | CBC, Cr, uric acid, AST or ALT, Alb, ALP, blood pressure | Cr every 2 wk until dose is stable, then monthly; CBC, potassium, AST or ALT, Alb, and ALP every 1-3 mo; drug levels only with doses >3 mg/kg/day |

| Tacrolimus | 1-4 mg/day in 2 doses at the same time every day | Cautious use in liver or renal insufficiency | Renal insufficiency, neurotoxicity, malignancy, infections, hyperkalemia | Cr, potassium, AST or ALT, glucose, blood pressure | Once a week for the first 3-4 wk, then every 1-3 mo; monitor drug trough levels |

| Rituximab | 1000 mg on day 1 and 15 | None | HBV reactivation (rare) | CBC, Cr, AST or ALT, HBV serology (high-risk patients), TST | CBC and platelets |

Note that placebo-controlled studies have failed to demonstrate efficacy in controlled clinical trials.

Alb, Serum albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; Bil, bilirubin; CBC, complete blood cell count; Cr, serum creatinine; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HBV, hepatitis B; LFTs, liver function tests; MTX, methotrexate; TST, tuberculin skin testing; ULN, upper limit of normal; WBC, white blood cell count.

From Firestein GS et al: Firestein & Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2021, Elsevier.

Figure 4 Recommended Drugs for the Treatment of SLE According to Stratification of Disease Severity

The grading of recommendation/level of evidence refers to extrarenal manifestations. aPL, Antiphospholipid antibodies; AZA, azathioprine; BEL, belimumab; CNI, calcineurin inhibitors; CYC, cyclophosphamide; GC, glucocorticoids; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate; PO, per os; Pre, prednisone; RTX, rituximab; SLEDAI, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index.

From Firestein GS et al: Firestein & Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2021, Elsevier.

TABLE 6 Indications for Immunosuppressive Therapy in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

| General Indications |

| Involvement of major organs or extensive involvement of non-major organs (skin) refractory to other agents, or bothFailure to respond to or inability to taper glucocorticoids to acceptable doses (<7.5 mg/day) for long-term use |

| Specific Organ Involvement |

| Renal |

| Proliferative or membranous nephritis, or mixed |

| Hematologic |

Severe thrombocytopenia (platelets <20-30,000/mm3)Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-like syndrome

Severe autoimmune hemolytic or aplastic anemia (hemoglobin <8 g/dl) not responding to glucocorticoids |

| Pulmonary |

| Lupus pneumonitis and/or alveolar hemorrhage |

| Cardiac |

| Myocarditis with depressed left ventricular function, pericarditis with impending tamponade |

| Gastrointestinal |

| Abdominal vasculitis, peritonitis |

| Nervous System |

| Transverse myelitis, optic neuritis, psychosis refractory to glucocorticoids, mononeuritis multiplex, severe peripheral neuropathy, acute confusional state |

From Firestein GS et al: Firestein & Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2021, Elsevier.

TABLE E10 Treatment of Main Hematologic Features of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

| First-Line Therapy | Second-Line Therapy | Third-Line Therapy | Experimental Therapy |

|---|

| Thrombocytopenia | Glucocorticoids | Azathioprine

CYC

IVIG | RTXMMF

Cyclosporine | Thrombopoietin-receptor agonists |

| Autoimmune anemia | Glucocorticoids∗ | CYC

IVIG | MMFRTX

Danazol | |

| Pure RBC aplasia | Glucocorticoids∗ | CYC

IVIG | Danazol

Cyclosporine

MMF | EPO |

| Hemophagocytic syndrome | Glucocorticoids∗ | CYC

Cyclosporine

PE | IVIG†

RTX | |

| TTP | Glucocorticoids∗ | PECYC | RTX | |

CYC, Cyclophosphamide; EPO, erythropoietin; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; MMF, mycophenolate; PE, plasma exchange; RBC, red blood cell; RTX, rituximab; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

From Hochberg MC: Rheumatology, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

- Azathioprine can be used for thrombocytopenia or hemolytic anemia. Check for TPMT genetic mutation before the first use.

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or rituximab may be considered for severe leukopenia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, or autoimmune thrombocytopenia (Fig. E6).

FIG E6 Suggested Algorithm for the Management of Immune Thrombocytopenia in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

AZA, Azathioprine; CsA, cyclosporine A; GC, glucocorticoids; IS, immunosuppressive; IV CYC, intravenous cyclophosphamide; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; IV MP, intravenous methylprednisolone; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; PLTs, platelets; RTX, rituximab; TPO, thrombopoietin.

From Firestein GS et al: Firestein & Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2021, Elsevier.

- Central nervous system manifestations:

- Headaches are treated symptomatically. Most headaches will not be SLE-related and should be treated according to the underlying cause.

- Anticonvulsants and antipsychotics may be indicated.

- Standard therapy for other neuropsychiatric SLE symptoms is not established.

- Renal disease: The histologic classification of LN according to the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society is summarized in Table E11. Severity of LN is described in Table E12. Treatment recommendations for LN are summarized in Table E13. (Class III, IV, or IV/V with cellular crescents LN; see Table E14.) INDUCTION: 6-mo treatment.

TABLE E11 Histologic Classification of Lupus Nephritis According to the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society (2003)

| Class | Description |

|---|

| I | Minimal mesangial lupus nephritis |

| Normal glomeruli by light microscopy, but mesangial immune deposits by immunofluorescence |

| II | Mesangial proliferative lupus nephritis |

| Purely mesangial hypercellularity of any degree or mesangial matrix expansion by light microscopy, with mesangial immune deposits |

| A few isolated subepithelial or subendothelial deposits may be visible by immunofluorescence or electron microscopy but not by light microscopy |

| III | Focal lupus nephritis |

| Active or inactive focal, segmental, or global endocapillary or extracapillary glomerulonephritis involving <50% of all glomeruli, typically with focal subendothelial immune deposits, with or without mesangial alterations |

| IV | Diffuse lupus nephritis |

| Active or inactive diffuse, segmental, or global endocapillary or extracapillary glomerulonephritis involving ≥50% of all glomeruli, typically with diffuse subendothelial immune deposits, with or without mesangial alterations. This class is divided into diffuse segmental (IV-S) lupus nephritis when ≥50% of the involved glomeruli have segmental lesions and diffuse global (IV-G) when ≥50% of the involved glomeruli have global lesions. Segmental is defined as a glomerular lesion that involves less than half of the glomerular tuft. This class includes cases with diffuse wire loop deposits but with little or no glomerular proliferation. |

| V | Membranous lupus nephritis |

| Global or segmental subepithelial immune deposits or their morphologic sequelae by light microscopy and by immunofluorescence or electron microscopy, with or without mesangial alterations |

| Class V nephritis may occur in combination with class III or class IV, in which case both will be diagnosed. |

| Class V nephritis may show advanced sclerotic lesions. |

| VI | Advanced sclerotic lupus nephritis ≥90% of the glomeruli globally sclerosed without residual activity |

From Hochberg MC: Rheumatology, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

TABLE E12 Severity of Lupus Nephritis∗

| Histologic Class (ISN/RPS 2003) | ↓GFR† | Proteinuria >3 g per 24 hr | Adverse Histologic Features‡ |

|---|

| Mild | III | - | - | - |

| V | - | - | |

| Moderately severe | III | +/- | +/- | - |

| IV | - | +/- | - |

| V | - | + | |

| Severe | III-IV | +/- | +/- | + |

| IV | + | +/- | +/- |

| III-IV | +§ | +/- | +/- |

| V | + | + | |

| V + III-IV | +/- | +/- | +/- |

+, Presence of feature; -, absence of feature; ISN, International Society of Nephrology; RPS, Renal Pathology Society.

From Hochberg MC: Rheumatology, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

TABLE E13 Recommended Treatment of Lupus Nephritis

| Histologic Type or Severity | Type of Therapy |

|---|

| Induction | Maintenance |

|---|

| Proliferative |

| Mild | - High-dose glucocorticoids (0.5-1 mg/kg/day for 4-6 wk with gradual tapering to 0.125 mg/kg every other day within 3-4 mo) alone or in combination with AZA (1-2 mg/kg/day)

- If no response within 3-6 mo, treat as moderately severe.

| - Low-dose glucocorticoids (≤0.125 mg/kg on alternative days) alone or with AZA (1-2 mg/kg/day)

- Consider further gradual tapering at the end of each year of response

|

| Moderate | - MPA (MMF 3 g/day) with glucocorticoids (0.5 mg/kg/day for 4 wk; then taper) for 6 mo. Consider three initial pulses of IV MP (500-750 mg/pulse), or

- Pulse IV CYC (3 g over 3 mo) with glucocorticoids as above

- If no response within 6-12 mo, treat as severe.

| - Low-dose glucocorticoids (≤0.125 mg/kg on alternative days) with MPA (MMF 2 g/day) for 18-24 mo after initial response; then consider gradual tapering, or

- AZA (2 mg/kg/day)

|

| Severe | Monthly pulses of IV CYC (0.5-1 g/m2) in combination with pulse IV MP for 6 mo. Background glucocorticoids (0.5 mg/kg/day for 4 wk; then taper), or

- MPA (MMF 3 g/day)

- If no improvement, consider MPA, combination of MPA with calcineurin inhibitor, or rituximab.

| Low-dose glucocorticoids (≤0.125 mg/kg on alternative days) in combination with quarterly pulses of IV CYC for at least 1 yr beyond response, or

|

| Membranous |

| Mild | High-dose glucocorticoids alone or in combination with AZA (2 mg/kg/day) | Low-dose glucocorticoids alone or with AZA (1-2 mg/kg/day) |

| Moderate to severe | High-dose glucocorticoids in combination with MPA (MMF 3 g/day), or

- Bimonthly pulse IV CYC (0.5-1 g/m2, six pulses), or

- CsA (3-5 mg/kg/day) or tacrolimus

| - Low-dose glucocorticoids

- AZA (2 mg/kg/day)

- 1CsA (3 mg/kg/day) or tacrolimus

- MPA (MMF 2 g/day)

|

AZA, Azathioprine; CsA, cyclosporine A; IV CYC, intravenous cyclophosphamide; IV MP, intravenous methylprednisolone; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MPA, mycophenolic acid.

From Hochberg MC: Rheumatology, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

TABLE E14 Severity of Lupus Nephritis∗

| Proliferative Disease |

|---|

| Mild | Type III without severe histologic features (e.g., crescents, fibrinoid necrosis); low chronicity index (i.e., ≤3); normal renal function; non-nephrotic proteinuria |

| Moderately severe | Mild disease as defined above with partial or no response after the initial induction therapy or delayed remission (>12 mo), or focal proliferative nephritis with adverse histologic features or reproducible increase of at least 30% in serum creatinine levels, or diffuse proliferative nephritis (class IV) without adverse histologic features |

| Severe | Moderately severe as defined above but not remitting after 6 to 12 mo of therapy, or proliferative disease with impaired renal function and fibrinoid necrosis or crescents in >25% of glomeruli, or mixed membranous and proliferative nephritis, or proliferative nephritis with high chronicity alone or in combination with high activity (chronicity index >4 or chronicity index >3 and activity index >10), or rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (doubling of serum creatinine within 2-3 mo) |

| Membranous Nephropathy |

| Mild | Non-nephrotic proteinuria with normal renal function |

| Moderate | Nephrotic-range proteinuria with normal renal function at presentation |

| Severe | Nephrotic-range proteinuria with impaired renal function at presentation (at least 30% increase in serum creatinine) |

From Hochberg MC: Rheumatology, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

- The typical treatment induction period is 6 mo. The use of intravenous cyclophosphamide (CYC) with corticosteroids given at monthly intervals is more effective in preserving renal function than is treatment with glucocorticoids alone. Low-dose “Euro-Lupus” protocol may be equally efficacious and less toxic for certain populations (e.g., Caucasians, Blacks) than high-dose regimen. MMF is considered equivalent to CYC based on high-quality studies, with better tolerability and fertility profile. MMF may be preferred in African Americans and Hispanics. MMF and azathioprine are good options for maintenance treatment.

- There is interest in and positive data for use of calcineurin inhibitors, such as tacrolimus, for treatment of LN. Newer and possibly less toxic voclosporin has entered phase III trial and when added to MMF showed better results in renal responses compared with MMF alone.9

- Severe nonrenal organ disease:

- Evidence from systematic randomized controlled trials for non-renal lupus treatment is comparatively limited.

- High-dose intravenous CYC is used as an induction treatment. Azathioprine or MMF may be used as maintenance.

- IVIG may be considered in severe disease especially when concomitant infection is present.

- Plasmapheresis or plasma exchange may be considered in critical situations: First-line therapy in Guillain-Barré syndrome, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP); second-line for SLE-related hemolytic anemia, cerebritis, and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH). Infectious complications are common.

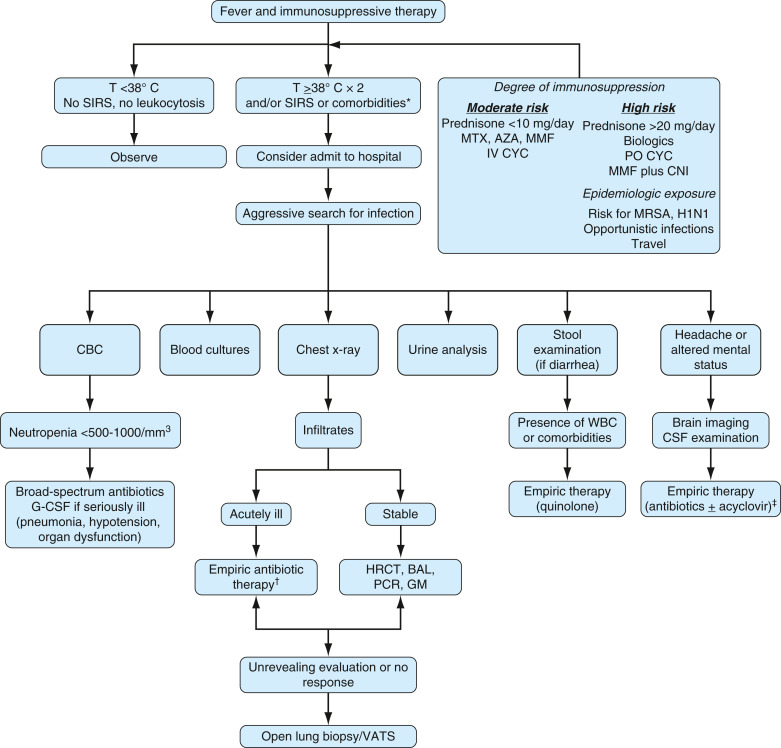

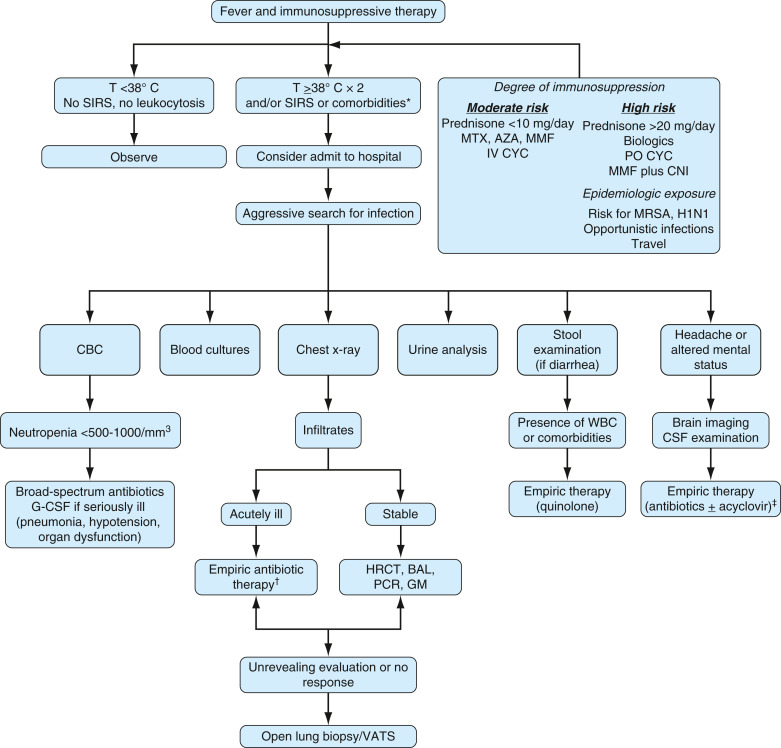

- Fever/infection post-immunosuppressive therapy

- Immunosuppressive therapy can result in neutropenia and increased susceptibility to infection

- Fig. E7 illustrates an approach to SLE patients with fever and other signs of infection post-immunosuppressive therapy

FIG E7 Initial Assessment and Management of Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Who Receive Immunosuppressive Therapy and are Seen with Fever or Other Symptoms and Signs Suggestive of Infection

∗Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS): T ≥38° C or <36° C, tachycardia (heart rate >90/min), tachypnea (respiratory rate >20/min), white blood cells (WBC) >12,000/mm3; comorbidities: Age older than 65 yr, diabetes, chronic cardiopulmonary disease. †Consider empiric therapy for Pneumocystis pneumonia in severe hypoxemia or diffuse pulmonary infiltrates. ‡Consider tuberculosis and other opportunistic central nervous system (CNS) infections. AZA, Azathioprine; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; CBC, complete blood count; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; GM, galactomannan; H1N1, influenza H1N1; HRCT, high-resolution chest tomography; IV CYC, intravenous cyclophosphamide; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MTX, methotrexate; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; T, temperature; VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopy.

Modified from Papadimitraki ED et al: Systemic lupus erythematosus: cytotoxic drugs. In Tsokos G [ed]: Systemic lupus erythematosus, ed 5, St Louis, 2010, Elsevier, pp. 1083-1108.

- Therapy targeting B cells:

- Rituximab: Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody. Randomized controlled trials for rituximab as an adjunct induction agent were negative in terms of both renal and nonrenal outcomes but were felt to be limited by study design. Some observational studies have shown efficacy in those who have failed other regimens.1,10

- Epratuzumab: An anti-CD22 agent. Studies initially showed positive data, but in July 2015 both phase III trials for SLE failed to meet their primary endpoint, and this medication is no longer studied.

- Belimumab: Decreases activation of B cells. When used in addition to standard therapy, patients on belimumab showed improvement in cutaneous and musculoskeletal disease. Belimumab-treated patients had decreased SLE activity, a reduced time to disease flare, and lower glucocorticoid exposure. Patients with central nervous system or serious kidney disease were excluded. There is interest in adding belimumab to standard LN regimen, but data from BLISS-LN are not yet available.8,11

- Abatacept: Downregulates T-cell activation. Data are limited regarding improvement in arthritis, fatigue, sleep if added to routine therapy. Negative data as adjunct agent for lupus arthritis when added to MMF or CYC. Shows limited positive efficacy in patients refractory to other treatments.1

- Interferon therapy: Interferon α (INFα) has been linked to increased disease activity in SLE. INFα blocking therapies are in phase II clinical trials. Sifalimumab, a monoclonal antibody against INFα, reduced moderate to severe mucocutaneous involvement in SLE and decreased active joint count and fatigue scores in preliminary data analysis. Development of sifalimumab has been terminated in favor of anifrolumab, a similar INFα blocking agent. The TULIP-1 study of that molecule did not meet response criteria based on score used in the BLISS trial. TULIP-2 used BICLA as a response measure and showed statistically significant improvement compared to placebo. The phase III trial is ongoing.12,13

- There is continuous interest in studying B-cell and interferon-based treatment, but no FDA approved treatment, other than noted earlier, is currently used clinically.

- Novel potential targeted treatment approaches may include blocking interleukin-17 (IL-17), IL-12/23, and JAK inhibitors (early data for 4-mg baricitinib showed positive results). Research remains very active and ongoing to find new therapeutic targets.14,15

- Recommended assessment and monitoring of patients with SLE with nonrenal, noncentral nervous system manifestations are summarized in Box 1.

- SLE in pregnancy (Table E15): Pregnancy in the setting of SLE is associated with a higher risk of complications compared with healthy women (preterm labor, unplanned cesarean delivery, fetal growth restriction, preeclampsia, and eclampsia). Ideally, conception should be attempted in a state of disease remission or stability. If pregnancy occurs during a period of disease relapse, medications need to be adjusted for maternal and fetal safety. Mothers with active SLE should be tested for anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies once before or early in pregnancy, due to their associated increase in risk for neonatal lupus and congenital heart block.16

BOX 1 Recommended Assessment and Monitoring of Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus With Nonrenal, Noncentral Nervous System Manifestations

ANA, Antinuclear antibodies; anti-RNP, anti-ribonucleoprotein; anti-Sm, anti-Smith; aPLs, antiphospholipid antibodies; BMD, bone mineral density; BMI, body mass index; CBC, complete blood count; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CLASI, cutaneous lupus erythematosus disease area and severity index; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CQ, chloroquine; CRP, C-reactive protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IS, immunosuppressive; LE, lupus erythematosus; NB, nota bene; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; VAS, visual analog scale.

Patient General AssessmentIn addition to the standard care of patients without lupus of the same age and sex, the assessment of patients with SLE must include the evaluation of: - Disease activity by a validated index at each visit

- Organ damage annually

- General quality of life by patient history and/or by a 0-10 VAS (patient global score) at each visit

- Comorbidities

- Drug toxicity

Cardiovascular Risk FactorsAt baseline and during follow-up at least once a year: - Assess smoking, vascular events (cerebral and cardiovascular), physical activity, oral contraceptives, hormonal therapies, and family history of cardiovascular disease

- Perform blood tests: Blood cholesterol, glucose

- Examine for blood pressure and BMI (and/or waist circumference)

- NB: Some patients may need more frequent follow-up (e.g., those taking glucocorticoids).

Osteoporosis RiskAll patients with SLE: - Should be assessed for adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, regular exercise, and smoking habits

- Should be screened and followed for osteoporosis according to existing guidelines (1) for postmenopausal women and (2) for patients taking glucocorticoids or on any other medication that may reduce BMD

Cancer RiskCancer screening is recommended according to the guidelines for the general population, including cervical smear tests. Infection RiskScreening: Patients with SLE should be screened for: - HIV based on the patient’s risk factors

- HCV and HBV based on the patient’s risk factors, particularly before IS drugs including high-dose glucocorticoids are given

- Tuberculosis, according to local guidelines, especially before IS drugs including high-dose glucocorticoids are given

- CMV testing should be considered during treatment in selected patients.

Vaccination: Patients with SLE are at high risk of infections, and prevention should be recommended. The administration of inactivated vaccines (especially flu and pneumococcus), following CDC guidelines for patients who are immunosuppressed, should be encouraged strongly in patients with SLE who take IS drugs, preferably administered when the SLE is inactive. For other vaccinations, an individual risk-benefit analysis is recommended. Monitoring: At follow-up visits, continuous assessment of the risk of infection by taking into consideration the presence of: - Severe neutropenia (<500 cells/mm3)

- Severe lymphopenia (<500 cells/mm3)

- Low IgG (<500 mg/dl)

Frequency of AssessmentsIn patients with no activity, no damage, and no comorbidity, assessments are recommended every 6-12 mo. During these visits, preventive measures should be emphasized. Laboratory AssessmentIt is recommended to monitor the following autoantibodies and complement: - At baseline: ANA, anti-dsDNA, anti-Ro, anti-La, anti-RNP, anti-Sm, antiphospholipid, C3, C4

- Reevaluation of aPLs in previously negative patients before pregnancy, surgery, transplant, and use of estrogen-containing treatments or in the presence of a new neurologic or vascular event; anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies before pregnancy; anti-dsDNA/C3 C4 may support evidence of disease activity or remission

Other laboratory assessments. At 6- to 12-mo intervals, patients with inactive disease should have: - CBC

- ESR

- CRP

- Serum albumin

- Serum creatinine (or eGFR)

- Urinalysis and urine protein-to-creatinine ratio

NB: If a patient is on a specific drug treatment, monitoring for that drug is required as well. Mucocutaneous InvolvementMucocutaneous lesions should be characterized, according to existing classification systems, as to whether they may be: - LE specific

- LE nonspecific

- LE mimickers

- Drug-related

Lesions should be assessed for activity and damage using validated indices (e.g., CLASI). Eye AssessmentIn patients treated with glucocorticoids or antimalarials, a baseline eye examination is recommended according to standard guidelines. An eye examination during follow-up is recommended: - In selected patients taking glucocorticoids (high risk of glaucoma or cataracts)

- In patients on antimalarial drugs. (Low risk: HCQ: No further testing is required until after 5 yr of baseline, and after the first 5 yr of treatment, eye assessment is recommended yearly; High risk: Eye assessment is recommended yearly, especially when using CQ.)

|

From Hochberg MC: Rheumatology, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

TABLE E15 Approach to the Management of Pregnancy in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Planning of pregnancy

- Discuss possible wish for pregnancy at every visit or change of medication

- Perform risk stratification according to disease status, presence of specific autoantibodies, and drugs used

- Ensure that lupus is inactive for at least 6 mo

- Discourage pregnancy if Cr >2 mg/dl

- Drugs allowed during pregnancy: GCs, HCQ, AZA, CsA

- Determine aPL and other antibodies that may be of relevance (anti-SSA, anti-SSB)

- After conception

- Obtain baseline serology and chemistry tests (Cr, Alb, uric acid, anti-dsDNA, C3/C4)

- Monitor closely blood pressure and proteinuria. Should this develop, differentiate between active nephritis and preeclampsia

- In women with anti-SSA and/or anti-SSB antibodies or with a prior episode of CHB, monitor for CHB between 18 and 24 wk of gestation

- Presence of generalized lupus activity, active urine sediment, and low serum complement are in favor of lupus nephritis

- For patients with APS, consider a combined heparin and aspirin regimen to reduce risk for pregnancy loss and thrombosis. Patients with APA may be treated with aspirin, although there are no adequate data to support its use

|

Alb, Serum albumin; aPL, antiphospholipid antibodies; APS, antiphospholipid antibodies/antiphospholipid syndrome; AZA, azathioprine; CHB, congenital heart block; Cr, serum creatinine; CsA, cyclosporin A; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; GCs, glucocorticoids; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine.

From Firestein GS et al: Firestein & Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2021, Elsevier.

- Recommended during pregnancy: Hydroxychloroquine, low-dose aspirin, antihypertensives (methyldopa, labetalol, nifedipine)

- Selective use allowed during pregnancy: NSAIDs, glucocorticoids, azathioprine, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, biologics

- Contraindicated: Cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, leflunomide