AUTHOR: Fred F. Ferri, MD

Graves disease is a hypermetabolic state caused by circulating immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies that bind to and activate the G-protein-coupled thyrotropin receptor. This activation stimulates follicular hypertrophy and hyperplasia, causing thyroid enlargement as well as increases in thyroid hormone production. It affects the thyroid, ocular muscles, and shin. It is characterized by thyrotoxicosis, diffuse goiter, and infiltrative ophthalmopathy (edema and inflammation of the extraocular muscles and an increase in orbital connective tissue and fat); infiltrative dermopathy characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of the dermis; accumulation of glycosaminoglycans; and occasionally edema.

| ||||||||||||

Graves disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism. It affects 3% of women and 0.5% of men during their lifetime. There is a slight increased incidence among young African Americans. The annual incidence of Graves disease-associated ophthalmopathy is 16 cases/100,000 women and 3 cases/100,000 men. It is more common in Whites than Asians. Cigarette smoking is a risk factor.

- Diffusely enlarged thyroid. Thyroid bruit may be present. Cervical lymphadenopathy also may be present

- Elevated systolic blood pressure with a widened pulse pressure

- Tachycardia, palpitations, tremor, hyperreflexia

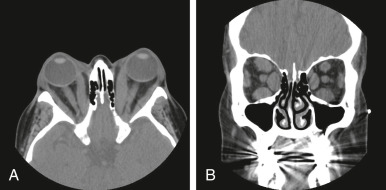

- Exophthalmos (50% of patients) (Fig. E1, Fig. E2), lid retraction (lid lag), in which contraction of the levator palpebrae muscles of the eyelids show immobility of the upper eyelid with downward rotation of the eye

- Nervousness, weight loss (weight gain in 10% of patients), heat intolerance, pruritus, muscle weakness, atrial fibrillation

- Increased sweating, brittle nails, clubbing of fingers

- Localized infiltrative dermopathy (1% to 2% of patients) is most frequent over the anterolateral aspects of the legs, commonly over the pretibial area (pretibial myxedema) but can be found at other sites (especially after trauma). It is nonpitting and indurated. It is typically patchy with a peau d’orange appearance to the skin

- Men may have gynecomastia, reduced libido, and erectile dysfunction. Women often have irregular menses

Autoimmune etiology: Thyrotropin receptor antibodies (TRAb) mediated activation of thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR). The activity of the thyroid gland is stimulated by the action of T cells, which induce specific B cells to synthesize antibodies against TSHRs in the follicular cell membrane.