AUTHORS: Anthony Sciscione, DO and Erin Bishop, MD

Mastitis is local painful inflammation of the breast that may or may not be accompanied by infection, flulike symptoms, and abscess formation.

| ||||||||||||||||

- Mastitis is the most common cause of inflammatory breast disease, and most cases are related to lactation (puerperal mastitis).

- In lactating mothers, mastitis typically occurs in the first 3 mo of the postpartum period (74% to 95% of cases).

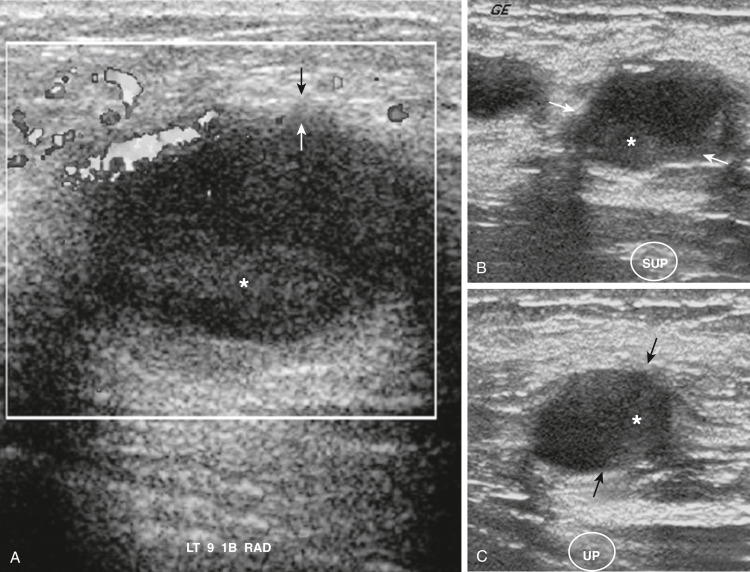

- When severe, mastitis can lead to a breast abscess (5% to 11%) or septicemia.

- Delayed diagnosis and treatment of lactational mastitis can lead to discontinuation of breastfeeding, breast tissue damage, or recurrence.

- In younger, nonlactating women, infection often presents as periductal mastitis and is caused by inflamed milk ducts near the nipple.

- Granulomatous mastitis (GM) is a rarer form of benign inflammation of the breast and also most commonly occurs in reproductive-age women. It generally affects the breast peripherally.

- Mastitis also can occur in infancy when there is breast hypertrophy from maternal hormones, called neonatal mastitis (NM).

- Previous mastitis

- Milk stasis and missed feedings, or extended periods between feedings such as when an infant begins to sleep through the night

- History of oversupply

- Cracked, fissured, or sore nipples

- Primiparity and infant attachment difficulties

- Cleft lip or palate or short frenulum in infant

- Use of manual breast pump

- Foreign material: Breast implants, nipple piercings

- Rapid weaning

- Smoking (periductal mastitis)

- Obesity (periductal mastitis)

- Conditions that impair immunity (peripheral or granulomatous mastitis): Diabetes, steroid use, rheumatoid arthritis

- Warmth, redness, noncyclic tenderness in breast

- Unilateral or bilateral

- Malaise, myalgias, fevers, chills, nausea

- Decreased milk output

- Breast is hard and swollen in a wedge-shaped area

- Lactational mastitis tends to be found in the breast periphery, whereas nonlactational mastitis tends to be peri- or sub-areolar

- In PM, breast mass near nipple with retraction or discharge

- In GM, enlarged axillary lymph nodes or sinus tract formation

- In lactational mastitis, infection occurs as a result of milk stasis and irritation of the milk ducts due to local immune response to milk proteins.

- Bacterial infection of subcutaneous tissue due to breaks in skin.

- Most commonly, Staphylococcus aureus; less common, S. epidermidis, group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, S. pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Candida albicans, Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Up to 40% are polymicrobial.

- GM results from inflammation with epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells and can be caused by etiologies like tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, foreign body reaction, parasitic and mycotic infections, or idiopathic.

- Periductal mastitis occurs following inflammation around nondilated subareolar ducts and often can progress to abscess formation. Peripheral abscesses can result from trauma, usually in the setting of comorbid conditions impairing immunity such as diabetes or use of immunosuppressive medications.

- Neonatal mastitis caused by S. aureus or gram-negative enteric bacteria.