Author: Husam Abu-Nejim, MD and Vishnu Kadiyala, MD and Aravind Rao Kokkirala, MD, FACC

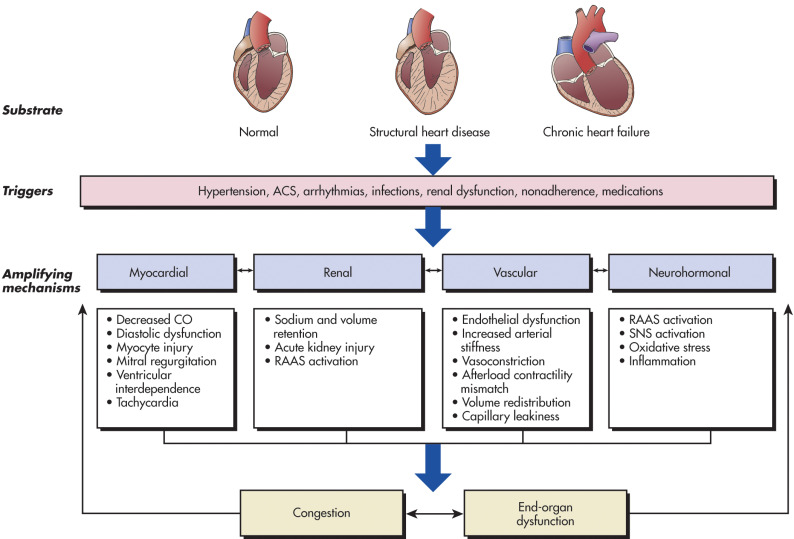

Heart failure (HF) is a complex clinical syndrome that can result from any structural or functional cardiac disorder that impairs the ability of the ventricle to fill with or eject blood. The cardinal manifestations of HF are dyspnea, fatigue, and fluid retention. The pathophysiology of HF (Fig. 1) is related to progressive activation of the neuroendocrine system to compensate for decreased effective circulating volume (Table 1), leading to total body volume overload and circulatory insufficiency.1 These events culminate in the development of pulmonary congestion as well as peripheral edema. Specifically, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is implicated; once activated, it can lead to volume expansion (sodium retention) and cardiac fibrosis (mediated through angiotensin II). Another recognized mechanism is disordered adrenergic stimulation as a key component of progression of disease. The term congestive heart failure (CHF) usually denotes a volume-overloaded status as a result of HF. Given that not all patients have volume overload at the time of the evaluation, congestive heart failure should be distinguished from the broader term heart failure.1

TABLE 1 Compensatory Mechanisms in Heart Failure

| Compensatory Response | Stimuli | Beneficial Effects | Adverse Effects | Potential Pharmacologic Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renin-angiotensin system activation | Maintain vital organ perfusion through vasoconstriction and sodium retention | |||

| Adrenergic activation | ↓CO/BP | β-Adrenergic blocking agents | ||

| Renal salt and water retention |

| |||

| ↑Natriuretic peptide secretion | Volume expansion (atrial stretch) | None known | Natriuretic peptides |

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BP, blood pressure; CO, cardiac output; LV, left ventricular; LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure.

From Sellke FW et al: Sabiston & Spencer surgery of the chest, ed 9, Philadelphia, 2016, Elsevier.

Figure 1 Schematic of the pathophysiology of acute heart failure.

ACS, Acute coronary syndrome; CO, cardiac output; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone; SNS, sympathetic nervous system.

(From Libby P et al: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 12, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.)

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) describes the following four stages of HF.2 This staging model was designed to emphasize the evolution and progression of HF over a continuum and the preventability of HF in at-risk patients.

- Stage A: Patients at high risk (e.g., with hypertension, atherosclerotic disease, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, cytotoxin, family history) for HF but without structural heart disease or symptoms of HF

- Stage B: Patients with structural heart disease (e.g., left ventricular [LV] dysfunction) but without symptoms of HF

- Stage C: Patients with structural heart disease with prior or current symptoms of HF

- Stage D: Patients with refractory HF requiring specialized interventions

In addition to the ACC/AHA stages described above, the New York Heart Association (NYHA) defines four functional classes of HF designed to describe the symptoms of stage C and D HF.3 The functional classes are intended to assess the symptoms of HF and may fluctuate with therapy. It should be noted that current guidelines employ the functional classes to aid in determination of appropriate treatment.

- Asymptomatic or symptomatic only at activity levels that would limit normal individuals

- Symptomatic with ordinary exertion (e.g., 2 city blocks or 1 flight of stairs in a faster than usual pace)

- Symptomatic with less than ordinary exertion (e.g., less than 2 city blocks or 1 flight of stairs)

- Symptomatic at rest

Table 2 compares the ACC/AHA and the NYHA classification. Table 3 describes a simplified classification and common clinical characteristics of patients with acute HF.

TABLE 3 Simplified Classification and Common Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Acute Heart Failure

| Clinical Classification | Symptom Onset | Triggers | Signs and Symptoms | Clinical Assessment | Course |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decompensated heart failure | Usually gradual | Noncompliance, ischemia, infections | Peripheral edema, orthopnea, dyspnea on exertion | Variable, high rehospitalization rate | |

| Acute hypertensive heart failure | Usually sudden | Hypertension, atrial arrhythmias, ACS | Dyspnea (often severe), tachypnea, tachycardia, rales common | ||

| Cardiogenic shock | Variable | Progression of advanced HF or major myocardial insult (e.g., large AMI, acute myocarditis) | End-organ hypoperfusion; oliguria, confusion, cool extremities |

ACS, Acute coronary syndrome; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CXR, chest x-ray film; LV, left ventricular; RV, right ventricular; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

From Zipes DP: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 11, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

TABLE 2 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Stages of Heart Failure (HF) Compared to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification

| ACC/AHA Stages of Heart Failure | NYHA Functional Classification | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A | At high risk for HF but without structural heart disease or symptoms of heart failure. | None | |

| B | Structural heart disease but without signs or symptoms of heart failure. | I | No limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause symptoms of heart failure. |

| C | Structural heart disease with prior or current symptoms of heart failure. | I | No limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause symptoms of heart failure. |

| II | Slight limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest, but ordinary physical activity results in symptoms of heart failure. | ||

| III | Marked limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest, but less than ordinary activity causes symptoms of heart failure. | ||

| D | Refractory heart failure requiring specialized interventions. | IV | Unable to carry on any physical activity without symptoms of heart failure, or symptoms of heart failure at rest. |

HF, Heart failure.

From Libby P et al: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 12, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

- Although HF has traditionally been classified as systolic vs. diastolic, this was dependent on the imaging modality used. With noted variation in the observed systolic function between studies, the ejection fraction serves as a better marker. HF is now categorized into HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Other common classifications include right-sided vs. left-sided and high-output vs. low-output.1 Systolic HF or HFrEF is defined by the presence of impaired contractility of the LV, as measured by ejection fraction (EF) ≤40% with clinical signs or symptoms of HF. In contrast, HFpEF has been described as evidence (clinical) of HF with an EF ≥50% with or without evidence of diastolic dysfunction. HF with mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF) is a newer concept, in which LVEF is between 41% and 49%. The term HFpEF improved is also sometimes used, used to describe patients who previously had HFrEF with an improvement in their EF.4

- Right-sided HF denotes peripheral signs and symptoms of HF without evidence of pulmonary congestion, as opposed to left-sided HF, which typically manifests with pulmonary congestion and subsequent signs and symptoms of right-sided HF.1 The most common cause of right-sided HF is left-sided HF. High-output HF involves signs and symptoms of HF but features an elevated cardiac output unable to meet the abnormally high metabolic demands of peripheral tissues and is the result of myriad systemic disorders (e.g., systemic arteriovenous fistulas, hyperthyroidism, anemia). The term acute decompensated HF (ADHF) refers to worsening of signs or symptoms of HF due to a wide range of causes. Of note, HF is not equivalent to cardiomyopathy or LV dysfunction. These latter terms describe the possible structural or functional reasons for the development of HF, whereas HF is a clinical syndrome characterized by specific symptoms and signs.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- There is variability in the reported demographics of HF due to heterogeneous definitions and classifications of HF. Incidence rate is lowest among White women and highest among Black men. African Americans have the highest risk for HF of the demographic groups with Blacks having a higher 5-yr mortality rate than Whites.1

- The lifetime risk of developing HF is 20% for Americans ≥40 yr of age.

- In the U.S., HF incidence has largely remained stable over the past several decades, with >650,000 new HF cases diagnosed annually.2

- Based on NHANES data, from 2013 to 2016, an estimated 6.2 million Americans ≥20 yr of age had HF. This represents an increase from an estimated 5.7 million U.S. adults with HF from 2009 to 2012.5

- Projections show that the prevalence of HF will increase 46% from 2012 to 2030, resulting in >8 million people ≥18 yr of age with HF.6

- There has been an increase in the prevalence of HF in the population over time. This is primarily due to improved treatment of hypertension and valvular and coronary disease, allowing patients to survive an early death only to later develop HF.6

- HF is primarily a condition of the elderly. Approximately 80% of patients hospitalized with HF are older than 65 yr. HF is the most common inpatient diagnosis in the U.S. for patients aged >65 yr.6

- HF incidence increases with age, rising from approximately 20 per 1000 individuals 65 to 69 yr to >80 per 1000 individuals among those >85 yr. Before age 75, the incidence of HF is higher in males, but both sexes are equally affected after this age cutoff.5

- In the U.S., 809,000 hospital discharges and 2.3 million emergency department visits/physician visits were associated with HF in 2016, which is a decline compared with 1.02 million hospital discharges in 2006.5,6

- Prevalence: 6.2 million persons in the U.S. and an estimated 26 million persons worldwide. The prevalence of HF is rising, especially in the elderly, particularly due to aging of the population and improved survival from other conditions.5

- The estimated (direct and indirect) cost of HF in the U.S. was >$40 billion in 2012, with over half of these costs spent on hospitalizations. The mean cost of HF-related hospitalizations is $23,077 per patient and is higher when HF was a secondary rather than the primary diagnosis.5

- HFrEF and HFpEF each make up about half of the overall HF burden of hospitalized HF events, half are in patients with HFrEF and the other half in patients with HFpEF.7

- The presence of ADHF services as an important juncture in the progression of HF, indicative of a worsening clinical course with increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization. An average hospitalization length for HF in the United States ranges around 4 to 5 days but carries a 1-yr mortality rate of ∼30%, over threefold of an increase from chronic, stable HF that does not require hospitalization.8,9

Several conditions are associated with an increased risk of developing HF. If these are identified and treated appropriately, it may be possible to delay, if not prevent, the onset of HF and also reduce rates of decompensations.4

- Hypertension: The incidence of HF is higher in patients with higher blood pressures, older age of the hypertensive patient, and in patients who have been hypertensive for longer.

- Diabetes mellitus: The incidence of HF is increased in patients with diabetes mellitus, independent of the presence of structural heart disease.

- Metabolic syndrome: Appropriately treating hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia can decrease the incidence of HF.

- Atherosclerotic disease: Patients with atherosclerotic disease are likely to develop HF.

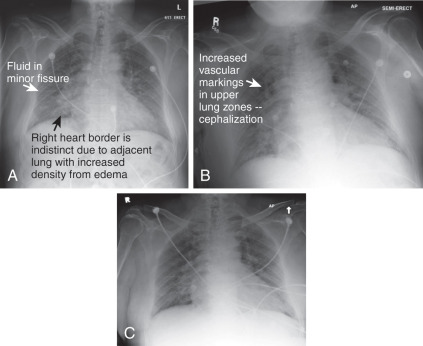

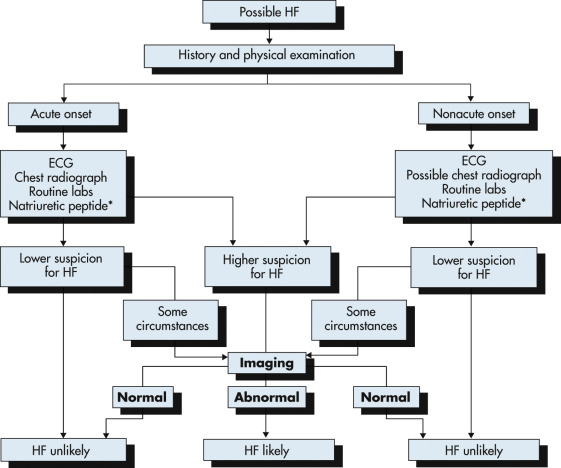

The clinical and physical examination findings should be given the highest priority when determining the diagnosis of HF (Fig. 2). These signs and symptoms are dependent on the severity of disease, precipitant factors, comorbid conditions, and whether the HF symptoms are predominantly right-sided or left-sided. Clues in the patient’s history when evaluating HF are summarized in Table 4.

- Common clinical manifestations are:2

- Dyspnea on exertion, that can progress to dyspnea at rest, caused by increasing pulmonary vascular congestion

- Orthopnea, caused by increased venous return in the recumbent position and further elevated pulmonary venous pressure

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND) resulting from multiple factors including increased venous return in the recumbent position, decreased Pao2, and decreased adrenergic stimulation of myocardial function during sleep

- Nocturnal angina resulting from increased myocardial oxygen demand (secondary to increased venous return in the recumbent position causing increased preload) in patients with concomitant coronary artery disease (CAD)

- Cheyne-Stokes respiration (alternating phases of apnea and hyperventilation) caused by prolonged circulation time from lungs to brain as a result of impaired cardiac output

- Fatigue, lethargy, and decreased functional capacity resulting from low cardiac output and hypoperfusion of peripheral tissues

- Lack of appetite and nausea, early satiety or a poor appetite

- Table 5 summarizes common presenting symptoms and signs of decompensated HF

- Physical examination (Table 6):2

- Fine pulmonary crackles, wheezes, tachypnea, hypoxia (due to elevated pulmonary pressures). Crackles may be absent in chronic and long-standing high pulmonary venous pressure because it allows for lymphatic drainage in the lungs to increase.

- Tachycardia and narrowed pulse pressure (due to increased sympathetic tone)

- S3 gallop, paradoxic splitting of S2, jugular venous distention, peripheral edema in dependent tissues, congestive hepatomegaly, ascites, and hepatojugular reflux (due to volume overload)

- Perioral and peripheral cyanosis, decreased capillary refill, pulsus alternans, and cool extremities (due to decreased cardiac output)

- Six common clinical presentations identified by European Society of Cardiology of Acute Heart Failure Syndromes:10

- Each of these scenarios may require different therapies to effectively stabilize and treat the patient

TABLE 6 Physical Findings of Heart Failure

a Indicative of more severe disease.

From Libby P et al: Braunwald’s heart disease; a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 12, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

TABLE 5 Common Presenting Symptoms and Signs of Decompensated Heart Failure

| Symptoms | Signs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predominantly Related to Volume Overload | |||

| Dyspnea (exertional, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, or at rest); cough; wheezing | Rales, pleural effusion | ||

| Foot and leg discomfort | Peripheral edema (legs, sacral) | ||

| Abdominal discomfort/bloating; early satiety or anorexia | Ascites/increased abdominal girth; right upper quadrant pain or discomfort; hepatomegaly/splenomegaly; scleral icterus | ||

| Increased weight | |||

| Elevated jugular venous pressure, abdominojugular reflux | |||

| Increasing S3, accentuated P2 | |||

| Predominantly Related to Hypoperfusion | |||

| Fatigue | Cool extremities | ||

| Altered mental status, daytime drowsiness, confusion, or difficulty concentrating | Pallor, dusky skin discoloration, Hypotension | ||

| Dizziness, pre-syncope, or syncope | Pulse pressure (narrow)/proportional pulse pressure (low) | ||

| Pulsus alternans | |||

| Other Signs and Symptoms of AHF | |||

| Depression | Orthostatic hypotension (hypovolemia) | ||

| Sleep disturbances | S4 | ||

| Palpitations | Systolic and diastolic cardiac murmurs | ||

AHF, Acute heart failure.

From Libby P et al: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 12, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

TABLE 4 Using the Medical History to Assess the Heart Failure Patient

From Libby P et al: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 12, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

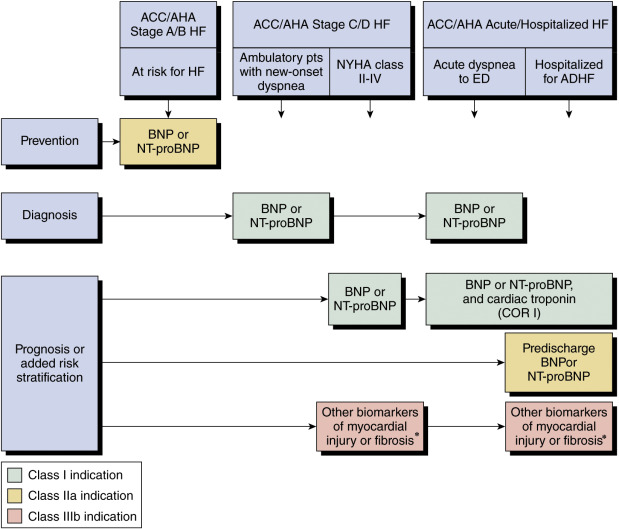

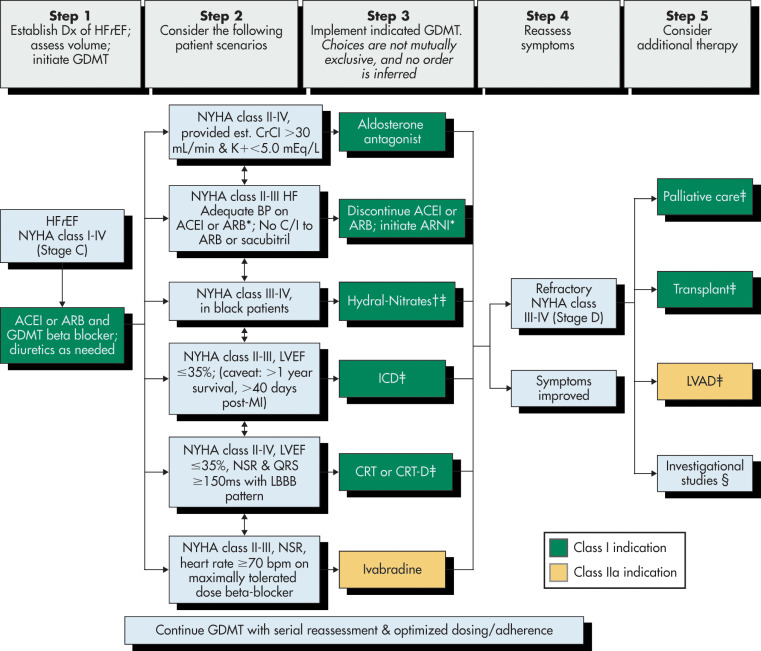

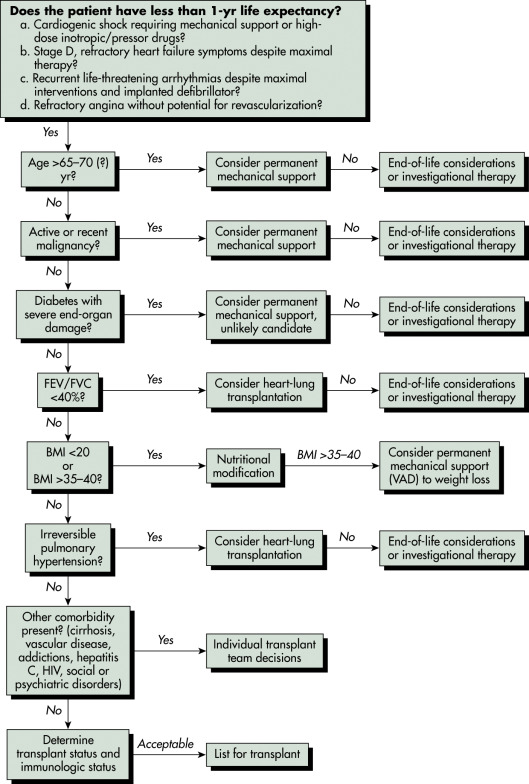

Figure 2 Flow chart for the evaluation of patients with heart failure (HF).

The diagnosis of HF is made using a combination of clinical judgment and initial and subsequent testing. Following thorough history and physical examination together with initial diagnostic testing, imaging (such as with echocardiography [ECG]) may still be necessary in ambiguous cases to definitively identify or exclude the diagnosis.

(From Libby P et al: Braunwald’s heart disease, a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 12, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.)

Acute precipitants of HF decompensation include nonadherence with salt restriction or medications (most common cause), any acute systemic illness, infection, arrhythmias (e.g., atrial fibrillation), ischemia or infarction, uncontrolled hypertension, new medications (e.g., negative inotropic agents such as calcium channel blockers/antiarrhythmic agents), NSAIDs, renal dysfunction, toxins (e.g., ethanol and anthracyclines), surgery, or valvular catastrophe.10

The dichotomy of whether HF occurs in the setting of preserved or reduced LV systolic function plays an important role in treatment strategies. Patients with HFpEF may have significant abnormalities in active relaxation and passive stiffness of the LV as well as valvular disease. HfrEF denotes poor pump function.10

- Abnormal LV systolic function:

- CAD (acute or chronic ischemia, myocardial infarction [MI], LV aneurysm), the most common cause of cardiomyopathy in the U.S., comprising 50% to 75% of HF patients

- Increased afterload or pressure overload (severe hypertension, aortic stenosis)

- Increased preload or volume overload (mitral regurgitation, aortic regurgitation)

- Cardiomyopathy: Idiopathic, infiltrative (nonischemic)

- Infectious (Chagas, myocarditis)

- Infiltrative (amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, hemochromatosis)

- Toxins (ethanol, cocaine, anthracyclines)

- Tachycardia induced (e.g., with atrial fibrillation)

- Preserved LV systolic function (Table 7):11

- Impaired relaxation (myocardial ischemia, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome)

- Tachyarrhythmia (featuring reduced diastolic filling time)

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy (myocardial stiffness, such as hypereosinophilic syndrome, amyloidosis, hemochromatosis)

- High cardiac output (thiamine deficiency, anemia, thyrotoxicosis, arteriovenous malformations)

- Increased afterload (uncontrolled hypertension, aortic stenosis, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy)

- Hypervolemia (oliguric renal failure, iatrogenic)

TABLE 7 Mechanisms/Factors Contributing to the Pathophysiology of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction

| Cardiovascular | |||

| LV Structure | |||

| LV Function | |||

| |||

| Cardiomyocyte | |||

| |||

| Extracellular Matrix | |||

| |||

| Extracardiac | |||

ADP,Adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; SPARC, secreted protein, acidic and rich in cysteine [osteonectin]; TGF, transforming growth vector.

From Mann DL et al: Braunwald’s heart disease, ed 10, Philadelphia, 2015, Elsevier.

- Left-sided HF

- Chronic hypoxemic pulmonary disease

- Valvular heart disease (mitral stenosis or regurgitation)

- Pulmonary embolism

- Primary pulmonary hypertension

- Right-to-left shunts that cause systemic hypoxemia (e.g., large patent foramen ovale and tetralogy of Fallot)

- Left-to-right shunts that cause volume overload (e.g., atrial and ventricular septal defects)

- Bacterial endocarditis (right-sided)

- Right ventricular infarction