Any changes in skin color, texture, or temperature? Pain in calves, feet, buttocks, or legs? What aggravates the pain? Walking? Sitting for long periods? Standing for long periods? Does it awaken you? What relieves the pain? Elevating legs? Rest? Lying down? Is there associated coldness, cyanosis, edema, varicosities, paresthesia, or tingling in legs or feet? Any leg veins that are ropelike, bulging, or contorted? Any sores on legs? Location? Size? Appearance? Onset? Duration? Delayed healing of sores? If client is male: Any changes in sexual activity? History of heart or blood vessel surgery? Family history of diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, or elevated cholesterol or triglyceride levels? Is client taking any drugs that may mimic arterial insufficiency? Self-care activities: Does client have well-fitting shoes? Does client wear constricting garments or hosiery? In what type of chair does client usually sit? Does client cross legs frequently? What amount and type of exercise does the client do? Does client smoke? Amount and for how long?

Risks for arterial peripheral vascular disease (PVD) related to tobacco smoking, age greater than 50 years (if client has a history of diabetes or other risk factors then age less than 50 years is a risk factor), family history of hypertension, coronary or PVD.

Risks for venous PVD include pregnancy, prolonged standing, limited physical activity/poor physical fitness, congenital or acquired vein wall weakness, female gender, increasing age, genetics (e.g., African American), obesity, lack of dietary fiber, use of constricting corsets/clothes.

After explaining what assessments you will be making, provide privacy while the client changes into an examination gown. See Figures 18-1 and 18-3 for diagrams of major arteries and veins.

| ASSESSMENT PROCEDURE | NORMAL FINDINGS | ABNORMAL FINDINGS |

|---|---|---|

| Arms | ||

| Inspection | ||

| Observe arm size and venous pattern; also look for edema. If there is an observable difference, measure bilaterally the circumference of the arms at the same locations with each remeasurement and record findings in centimeters. | Arms are bilaterally symmetric with minimal variation in size and shape. No edema or prominent venous patterning. | Lymphedema (

Abnormal Findings 18-1 ) results from blocked lymphatic circulation, which may be caused by breast surgery. It usually affects one extremity, causing induration and nonpitting edema. Prominent venous patterning with edema may indicate venous obstruction (Table 18-1). |

| Observe coloration of the hands and arms. | Color varies depending on the client’s skin tone, although color should be the same bilaterally (see Chapter 14 for more information). | Raynaud, a vascular disorder (

Abnormal Findings 18-1 ) caused by vasoconstriction or vasospasm of the fingers or toes, is characterized by rapid changes of color (pallor, cyanosis, and redness), swelling, pain, numbness, tingling, burning, throbbing, and coldness. Commonly occurs bilaterally; symptoms last minutes to hours. |

| Palpation | ||

| Palpate the client’s fingers, hands, and arms and note the temperature. | Skin is warm to the touch bilaterally from fingertips to upper arms. | A cool extremity may be a sign of arterial insufficiency. Cold fingers and hands, for example, are common findings with Raynaud. |

| Palpate to assess capillary refill time. Compress the nailbed until it blanches. Release the pressure and calculate the time it takes for color to return. This test indicates peripheral perfusion and reflects cardiac output. Note: Inaccurate findings may result if the room is cool, if the client has edema, has anemia, or if the client recently smoked a cigarette. | Capillary beds refill (and, therefore, color returns) in 2 seconds or less. | Capillary refill time exceeding 2 seconds may indicate vasoconstriction, decreased cardiac output, shock, arterial occlusion, or hypothermia. |

| Palpate the radial pulse. Gently press the radial artery against the radius (Fig. 18-6). Note elasticity and strength. Assess pulse amplitude (Box 18-1). Note: For difficult-to-palpate pulses, use a Doppler ultrasound device. | Radial pulses are bilaterally strong (2+). Artery walls have a resilient quality (bounce). | Increased radial pulse volume indicates a hyperkinetic state (4+ or bounding pulse). Diminished (1+) or absent (0) pulse suggests partial or complete arterial occlusion (which is more common in the legs than the arms). The pulse could also be decreased from Buerger disease or scleroderma. |

| Palpate the ulnar pulses. Apply pressure with your first three fingertips to the medial aspects of the inner wrists. The ulnar pulses are not routinely assessed because they are located deeper than the radial pulses and are difficult to detect. Palpate the ulnar arteries if you suspect arterial insufficiency (Fig. 18-7). | The ulnar pulses may not be detectable. | Obliteration of the pulse may result from compression by external sources, as in compartment syndrome. Lack of resilience or inelasticity of the artery wall may indicate arteriosclerosis. |

| Palpate the brachial pulses if you suspect arterial insufficiency. Place the first three fingertips of each hand at the client's right and left medial antecubital creases. Alternatively, palpate the brachial pulse in the groove between the biceps and triceps. Assess pulse amplitude (see Box 18-1). | Brachial pulses have equal strength bilaterally. | Brachial pulses are increased, diminished, or absent. |

| Palpate the epitrochlear lymph nodes. Take the client's left hand in your right hand as if you were shaking hands. Flex the client's elbow about 90 degrees. Use your left hand to palpate behind the elbow in the groove between the biceps and triceps muscles (Fig. 18-8). If nodes are detected, evaluate for size, tenderness, and consistency. Repeat palpation on the opposite arm. | Normally, epitrochlear lymph nodes are not palpable. | Enlarged epitrochlear lymph nodes may indicate an infection in the hand or forearm, or they may occur with generalized lymphadenopathy. Enlarged lymph nodes may also occur because of a lesion in the area. |

| Perform the Allen test to evaluate patency of the radial or ulnar arteries when patency is questionable or before such procedures as a radial artery puncture. First assess ulnar patency. Have the client rest the hand palm side up on the examination table and make a fist. Then use your thumbs to occlude the radial and ulnar arteries (Fig. 18-9A). Continue pressure to keep both arteries occluded and have the client release the fist (Fig. 18-9B). Note that the palm remains pale. Release the pressure on the ulnar artery and watch for color to return to the hand. To assess radial patency, repeat the procedure as before, but at the last step, release pressure on the radial artery (Fig. 18-9C). | Pink coloration returns to the palms within 3 to 5 seconds if the ulnar artery is patent. Pink coloration returns within 3 to 5 seconds if the radial artery is patent. | With arterial insufficiency or occlusion of the ulnar artery, pallor persists. With arterial insufficiency or occlusion of the radial artery, pallor persists. |

| Note:Opening the hand into exaggerated extension may cause persistent pallor (false-positive Allen test). | ||

Mark locations on arms with a permanent marker to ensure the exact same locations are used with each reassessment.

NECROTIC GREAT TOE WITH BLISTERS ON TOES AND FOOT

Arterial ulcer. Great toe is necrotic with blisters on the toes and foot seen in arterial insufficiency.

Dramatic blanching of fingers on both hands in Raynaud phenomenon.

| ASSESSMENT PROCEDURE | NORMAL FINDINGS | ABNORMAL FINDINGS |

|---|---|---|

| Ask the client to lie supine. Drape the groin area and place a pillow under client's head. Observe skin color while inspecting both legs from the toes to the groin. | Pink color for lighter-skinned clients and pink or red tones visible under darker-pigmented skin. There should be no changes in pigmentation. | Pallor, especially when elevated, and rubor, when dependent, suggest arterial insufficiency. Dark-colored toes and blisters are seen with arterial insufficiency and gangrene (which causes dry, shriveled skin changing from blue to black before sloughing off) (

Abnormal Findings 18-1 ). Cyanosis when dependent suggests venous insufficiency. A rusty, ruddy, or brownish pigmentation (rubor) around the ankles indicates venous insufficiency. (Refer to Tables 18-2 and 18-3 to differentiate between venous insufficiency and arterial insufficiency.) See Figure 18-10A and B. |

| Inspect top and bottom of feet for lesions or ulcers. Palpate for sensation. Inspect for edema. Inspect the legs for unilateral or bilateral edema. Note veins, tendons, and bony prominences. If the legs appear asymmetric, use a centimeter tape to measure in four different areas: circumference at mid-thigh, largest circumference at the calf, smallest circumference above the ankle, and across the forefoot. Compare both extremities at the same locations. Note: Taking a measurement in centimeters from the patella to the location to be measured can aid in getting the exact location on both legs. If additional readings are necessary, use a felt-tipped pen to ensure exact placement of the measuring tape. | Feet are free of lesions or ulcerations. Client has bilateral equal sensation to both feet. Identical size and shape bilaterally; no swelling or atrophy. | Ulcers of the feet may be seen with diabetic neuropathy, neurologic disorders, or Hansen disease (

Abnormal Findings 18-2 ).Bilateral edema may be detected by the absence of visible veins, tendons, or bony prominences. Bilateral edema usually indicates a systemic problem (such as heart failure or chronic venous insufficiency) or a local problem (such as lymph edema, which tends to be unilateral) (Dean et al., 2019). Bilateral edema may also be caused by prolonged standing or sitting (orthostatic edema). Unilateral edema is characterized by a 1-cm difference in measurement at the ankles or a 2-cm difference at the calf, and a swollen extremity. It is usually caused by venous stasis due to insufficiency or an obstruction ( Abnormal Findings 18-3 ). It may also be caused by lymphedema. A difference in measurement between legs may also be due to muscular atrophy. Muscular atrophy usually results from disuse due to stroke or from being in a cast for a prolonged time. |

| Inspect distribution of hair on legs. | Hair covers the skin on the legs and appears on the dorsal surface of the toes. | Loss of hair on the legs suggests arterial insufficiency. often, thin, shiny skin is noted as well. |

| Inspect for lesions or ulcers. | Legs are free of lesions or ulcerations. | Ulcers with smooth, even margins that occur at pressure areas, such as the toes and lateral ankle, result from arterial insufficiency. Ulcers with irregular edges, bleeding, and possible bacterial infection that occur on the medial ankle result from venous insufficiency (see Fig. 18.10A and B and

Abnormal Findings 18-3 ). |

| Palpate edema. If edema is noted during inspection, palpate the area to determine if it is pitting or nonpitting. Press the edematous area with the tips of your fingers, hold for a few seconds, then release. | No edema (pitting or nonpitting) present in the legs. | If the depression does not rapidly refill and the skin remains indented on release, pitting edema is present. It is associated with systemic problems, such as heart failure or hepatic cirrhosis; local causes such as venous stasis due to insufficiency or obstruction; or prolonged standing or sitting (orthostatic edema). A 1+ to 4+ scale is used to grade the severity of pitting edema, with 4+ being most severe (Fig. 18-11). |

| Palpate bilaterally for temperature of the feet and legs. Use the backs of your fingers. Compare your findings in the same areas bilaterally. Note location of any changes in temperature. | Toes, feet, and legs are equally warm bilaterally. | Generalized coolness in one leg or change in temperature from warm to cool as you move down the leg suggests arterial insufficiency. Increased warmth in the leg may be caused by superficial thrombophlebitis resulting from a secondary inflammation in the tissue around the vein. Note: Bilateral coolness of the feet and legs may suggest room is too cool, client recently smoked a cigarette, or client is anemic or anxious. These factors cause vasoconstriction. |

| Palpate the superficial inguinal lymph nodes. First, expose the client's inguinal area, keeping the genitals draped. Feel over the upper medial thigh for the vertical and horizontal groups of superficial inguinal lymph nodes. If detected, determine size, mobility, and tenderness. Repeat palpation on the opposite thigh. | Nontender, movable lymph nodes up to 1 or even 2 cm are commonly palpated. | Lymph nodes larger than 2 cm with or without tenderness (lymphadenopathy) may be from a local infection or generalized lymphadenopathy. Fixed nodes may indicate malignancy. |

| Palpate the femoral pulses. Ask the client to bend the knee and move it out to the side. Press deeply and slowly below and medial to the inguinal ligament. Use two hands if necessary. Release pressure until you feel the pulse. Repeat palpation on the opposite leg. Compare pulse amplitude (Box 18-1) bilaterally (Fig. 18-12). | Femoral pulses strong and equal bilaterally. | Weak or absent femoral pulses indicate partial or complete arterial occlusion. |

| Auscultate the femoral pulses. If arterial occlusion is suspected in the femoral pulse, position the stethoscope over the femoral artery and listen for bruits. Repeat for other artery (Fig. 18-13). | No sounds auscultated over the femoral arteries. | Bruits over one or both femoral arteries suggest partial obstruction of the vessel and diminished blood flow to the lower extremities. |

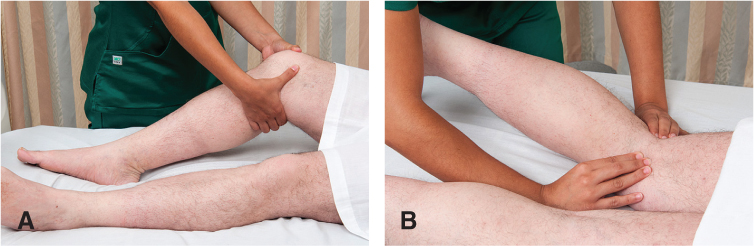

| Palpate the popliteal pulses. Ask the client to raise (flex) the knee partially. Place your thumbs on the knee while positioning your fingers deep in the bend of the knee. Apply pressure to locate the pulse. It is usually detected lateral to the medial tendon (Fig. 18-14). Assess pulse amplitude (see Box 18-1). Palpating the popliteal pulse with the client (A) supine and (B) prone. If you cannot detect a pulse, try palpating with the client in a prone position. Partially raise the leg and place your fingers deep in the bend of the knee. Repeat palpation in opposite leg and note amplitude bilaterally. Note: If you cannot detect a pulse, try palpating with the client in a prone position. Partially raise the leg, and place your fingers deep in the bend of the knee. Repeat palpation in opposite leg and note amplitude bilaterally. With continued difficulty, use a Doppler device to assess pulses. | It is not unusual for the popliteal pulse to be difficult or impossible to detect, and yet for circulation to be normal. | Although normal popliteal arteries may be nonpalpable, an absent pulse may also be the result of an occluded artery. Further circulatory assessment such as temperature changes, skin color differences, edema, hair distribution variations, and dependent rubor (dusky redness) distal to the popliteal artery assists in determining the significance of an absent pulse. Cyanosis may be present yet more subtle in darker-skinned clients (Mann, 2013). |

| Palpate the dorsalis pedis pulses. Dorsiflex the client's foot and apply light pressure lateral to and along the side of the extensor tendon of the big toe. The pulses of both feet may be assessed at the same time to aid in making comparisons. Assess pulse amplitude (see Box 18-1) bilaterally (Fig. 18-15). Note: It may be difficult or impossible to palpate a pulse in an edematous foot. A Doppler ultrasound device may be useful in this situation. | Dorsalis pedis pulses are bilaterally strong. This pulse is congenitally absent in 5% to 10% of the population. | A weak or absent pulse may indicate impaired arterial circulation. Further circulatory assessments (temperature and color) are warranted to determine the significance of an absent pulse. |

| Palpate the posterior tibial pulses. Palpate behind and just below the medial malleolus (in the groove between the ankle and the Achilles tendon) (Fig. 18-16). Palpating both posterior tibial pulses at the same time aids in making comparisons. Assess pulse amplitude (see Box 18-1) bilaterally. Note: Edema in ankles may make it difficult to palpate a posterior tibial pulse. A Doppler may be useful to assess the pulse. | The posterior tibial pulses should be strong bilaterally. However, in about 15% of healthy clients, the posterior tibial pulses are absent. | A weak or absent pulse indicates partial or complete arterial occlusion. |

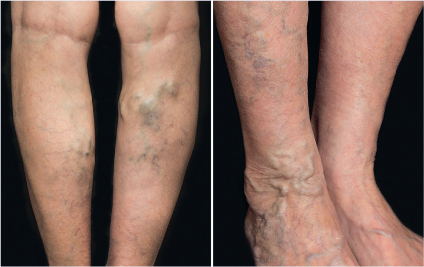

| Inspect for varicosities and thrombophlebitis. Ask the client to stand because varicose veins may not be visible when the client is supine and not as pronounced when the client is sitting. As the client is standing, inspect for superficial vein thrombophlebitis. To fully assess for a suspected phlebitis, lightly palpate for tenderness. If superficial vein thrombophlebitis is present, note redness or discoloration on the skin surface over the vein. | Veins are flat and barely seen under the surface of the skin. | Varicose veins may appear as distended, nodular, bulging, and tortuous, depending on severity. Varicosities are common in the anterior lateral thigh, lower leg, the posterior lateral calf, and anus (known as hemorrhoids). Varicose veins (

Abnormal Findings 18-3 ) result from incompetent valves in the veins, weak vein walls, or an obstruction above the varicosity. Despite venous dilation, blood flow is decreased and venous pressure is increased. Superficial vein thrombophlebitis is marked by redness, thickening, and tenderness along the vein. Aching or cramping may occur with walking. Swelling and inflammation are often noted.Diagnostic testing, such as venous Doppler ultrasound of the legs, and referral are indicated for a definitive diagnosis. |

| Special Tests for Arterial or Venous Insufficiency | ||

| Perform position change test for arterial insufficiency. If pulses in the legs are weak, further assessment for arterial insufficiency is warranted. The client should be in a supine position. Place one forearm under both of the client's ankles and the other forearm underneath the knees. Raise the legs about 12 inches above the level of the heart. As you support the client's legs, ask the client to pump the feet up and down for about a minute to drain the legs of venous blood, leaving only arterial blood to color the legs. | Feet pink to slightly pale in color in the light-skinned client with elevation. Inspect the soles in the dark-skinned client, although it is more difficult to see subtle color changes in darker skin. When the client sits up and dangles the legs, a pinkish color returns to the tips of the toes in 10 seconds or less. The superficial veins on top of the feet fill in 15 seconds or less. | Marked pallor with legs elevated is an indication of arterial insufficiency. Return of pink color that takes longer than 10 seconds and superficial veins that take longer than 15 seconds to fill suggest arterial insufficiency. Persistent rubor (dusky redness) of toes and feet with legs dependent also suggests arterial insufficiency (see

Abnormal Findings 18-1 ). |

| At this point, ask the client to sit up and dangle legs off the side of the examination table. Note the color of both feet and the time it takes for color to return (Fig. 18-17). Note: This assessment maneuver will not be accurate if the client has PVD of the veins with incompetent valves. | Normal responses with absent pulses suggest that an adequate collateral circulation has developed around an arterial occlusion. | |

| Manual compression test | ||

| If the client has varicose veins, perform manual compression to assess the competence of the vein's valves. Ask the client to stand. Firmly compress the lower portion of the varicose vein with one hand. Place your other hand 6-8 in. above your first hand. Feel for a pulsation to your fingers in the upper hand (Fig. 18-18). Repeat this test in the other leg if varicosities are present. | No pulsation is palpated if the client has competent valves. | You will feel a pulsation with your upper fingers if the valves in the veins are incompetent. |

| Trendelenburg test If the client has varicose veins ( Abnormal Findings 18-3 ), perform the Trendelenburg test to determine the competence of the saphenous vein valves and the retrograde (backward) filling of the superficial veins. The client should lie supine. Elevate the client's leg 90 degrees for about 15 seconds or until the veins empty. With the leg elevated, apply a tourniquet to the upper thigh.Note:Arterial blood flow is not occluded if there are arterial pulses distal to the tourniquet. Assist the client to a standing position and observe for venous filling. Remove the tourniquet after 30 seconds and watch for sudden filling of the varicose veins from above. | Saphenous vein fills from below in 30 seconds. If valves are competent, there will be no rapid filling of the varicose veins from above (retrograde filling) after removal of tourniquet. | Filling from above with the tourniquet in place and the client standing suggests incompetent valves in the saphenous vein. Rapid filling of the superficial varicose veins from above after the tourniquet has been removed also indicates retrograde filling past incompetent valves in the veins. |

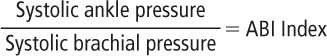

| Determine ankle-brachial index (ABI), also known as ankle-brachial pressure index (ABPI). Although this advanced skill is usually performed in a cardiovascular center, it is important to know how the test is performed and the implications. If the client has symptoms of arterial occlusion, the ABPI should be used to compare upper- and lower-limb systolic blood pressure. The ABI is the ratio of the ankle systolic blood pressure to the arm (brachial) systolic blood pressure: The ABI is considered an accurate objective assessment for determining the degree of peripheral arterial disease (PAD). It detects decreased systolic pressure distal to the area of stenosis or arterial narrowing and allows the nurse to quantify this measurement. | Generally, the ankle pressure in a healthy person is the same or slightly higher than the brachial pressure, resulting in an ABI of approximately 1, or no arterial insufficiency. A normal resting ABI is 1.0 to 1.4. This means that client’s ankle blood pressure is the same or greater than the brachial arm pressure and that there is no significant narrowing or blockage of blood flow (Aboyans et al., 2012). | Early recognition of cardiovascular disease, even in asymptomatic people, can be determined using ABI measurements. People who smoke, are physically inactive, have a body mass index >30, or are hypertensive are more likely to have an abnormal ABI, suggesting PAD (Patel et al., 2018). If the ABI is 0.91 to 1.00, it is considered borderline abnormal. Abnormal values for the resting ABI are 0.9 or lower and 1.40 or higher; both of these indicate an increased chance of narrowed arteries in various areas of the body and increase one’s risk of having a heart attack or stroke (Aboyans et al., 2012; My Cleveland Clinic, 2019). Abnormal values for the resting ABI are often associated with diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, and hyperparathyroidism. Medial calcific sclerosis produces falsely elevated ankle pressure by making the vessels noncompressible. |

Hair loss of lower extremities occurs with aging and may not be an absolute sign of arterial insufficiency.

Inspect for rigid, tortuous veins and arteries (decreased venous return and competency) because varicosities are common in older adults.

Prominent, bulging veins are common. Varicosities are common in the older adult and are considered a problem only if ulcerations, signs of thrombophlebitis, or cords are present. Cords are nontender, palpable veins having a rubber tubing consistency (see

Abnormal Findings 18-3

).Blood pressure increases as elasticity decreases in arteries with proportionately greater increase in systolic pressure, resulting in a widening of pulse pressure.

Older clients with arterial disease may not have the classic symptoms of intermittent claudication but may experience coldness, color change, numbness, and abnormal sensations.

Superficial thrombophlebitis resulting from thrombus formation in the superficial veins. often seen with unilateral localized pain, achiness, edema, redness, and warmth to touch.

A 44-year-old female with massive localized lymphedema.

VARICOSE VEINS ON A FEMALE’S LEGS

Photo credits: Superficial thrombophlebitis, Reprinted with permission from Jensen, S. (2015). Nursing health assessment: A best practice approach. Wolters Kluwer; lymphedema, reprinted with permission from Baranoski, S., & Ayello, E. (2015). Wound care essentials. Wolters Kluwer.)African Americans in the United States have higher rates of PAD than Whites and Hispanics (NHLBI, 2019).

VenousNews (2019) reported the highest rate of venous insufficiency is in White women but noted significant differences in incidence and prevalence when comparing racial groups and increasing age.

African Americans have a higher number of lower leg veins than do Whites. This may account for the lower prevalence rates of varicose veins in people of African descent (1%-2%) when compared to those of Whites (10%-18%) (Caggiati, 2013).

However, PAD was more prevalent in African Americans and lower in Asian Americans as compared to Whites (Vitalis et al., 2017).