Symptoms

Decreased vision, pain, diplopia, or may be asymptomatic. History of trauma, may be remote.

Signs

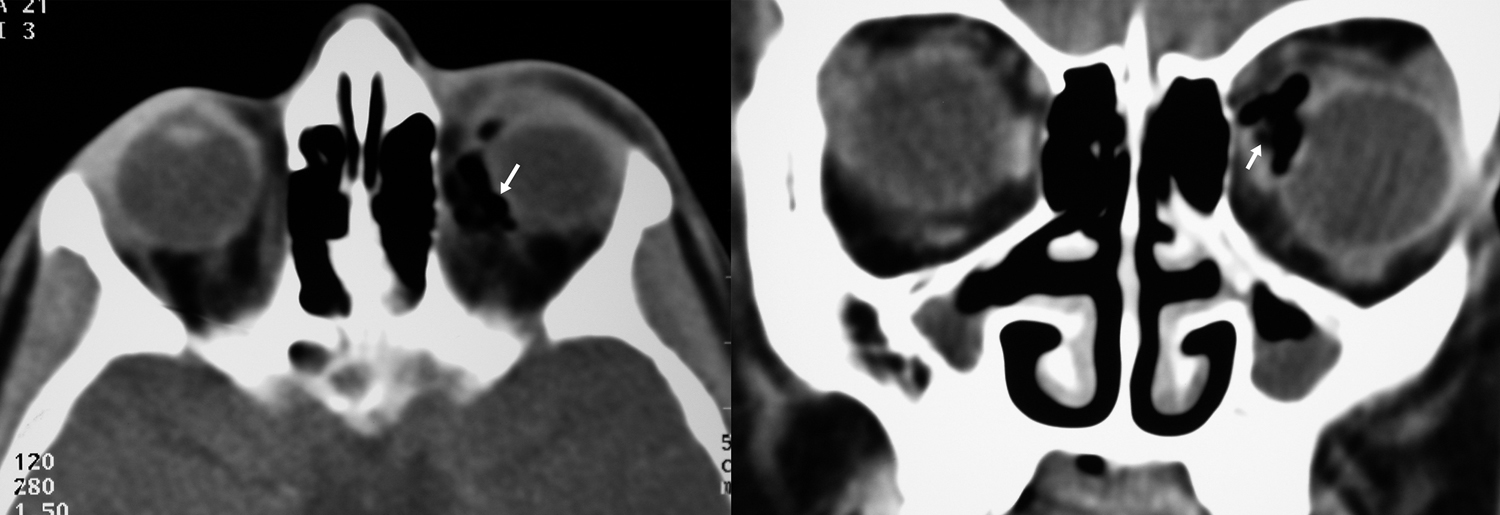

(See Figures 3.12.1 and 3.12.2.)

Critical

Orbital foreign body identified by clinical examination, radiograph, CT scan, and/or orbital ultrasonography.

Other

A palpable orbital mass, limitation of ocular motility, proptosis, eyelid or conjunctival laceration, erythema, edema, or ecchymosis of eyelids. Presence of an afferent pupillary defect may indicate TON.

Types of Foreign Bodies

- Poorly tolerated (often lead to inflammation or infection): Organic (e.g., wood or vegetable matter; see Figure 3.12.3), chemical (e.g., diesel fuel), and certain retinotoxic metallic foreign bodies (especially copper).

- Fairly well tolerated (typically produce a chronic low-grade inflammatory reaction): Alloys that are <85% copper (e.g., brass, bronze).

- Well tolerated (inert materials): Stone, glass, plastic, iron, lead, steel, aluminum, and most other metals and alloys, assuming that they were relatively clean on entry and have a low potential for microbial inoculation.

Workup

- History: Determine the nature of the injury and the foreign body. Must have high index of suspicion in all trauma. Remember that children are notoriously poor historians.

- Complete ocular and periorbital examination with special attention to pupillary reaction, IOP, and posterior segment evaluation. Carefully examine for an entry wound: at least 50% of conjunctival entry wounds are missed on clinical examination. Rule out occult globe rupture. Gentle gonioscopy may be needed.

- CT scan of the orbit and brain (axial, coronal, and parasagittal views, with no larger than 1-mm sections of the orbit) is the initial study of choice regardless of foreign body material to rule out possible metallic foreign body. CT may miss certain materials (e.g., wood may look like air). If wood or vegetative matter is suspected, it is helpful to inform the radiologist in advance. Any lucency within the orbit can then be measured in Hounsfield units to differentiate wood from air. MRI is never the initial study in suspected foreign body and is contraindicated if a metallic foreign body is suspected or cannot be excluded, but may be a helpful adjunct to CT (especially if a wooden foreign body is suspected) once metallic foreign bodies are ruled out.

- Based on imaging studies, determine the location of the intraorbital foreign body and rule out optic nerve or central nervous system involvement (frontal lobe, cavernous sinus, carotid artery).

- Perform orbital B-scan ultrasonography if a foreign body is suspected, but not detected, by CT scan. B-scan is only helpful in the anterior orbit.

- Culture any drainage sites or foreign material as appropriate.

Treatment

- NEVER remove an intraorbital foreign body at the slit lamp without first obtaining imaging to evaluate the depth and direction of penetration. Premature removal may result in intracranial bleeding, cerebrospinal fluid leakage, worsening of intraocular injury, etc.

- Surgical exploration, irrigation, and extraction, based on the following indications:

- Signs of infection or inflammation (e.g., fever, proptosis, restricted motility, severe chemosis, a palpable orbital mass, abscess on CT scan).

- Any organic or wooden foreign body (because of the high risk for infection and sight-threatening complications). Many copper foreign bodies require removal because of a marked inflammatory reaction.

- Infectious fistula formation.

- Signs of optic nerve compression or gaze-evoked amaurosis (decreased vision in a specific gaze).

- A large or sharp-edged foreign body (independent of composition) that can be easily extracted.

- In the setting of a ruptured globe, the globe must be repaired first. The orbital foreign body may be removed as necessary thereafter.

- Tetanus toxoid as indicated (see APPENDIX 2, TETANUS PROPHYLAXIS).

- Consider hospitalization:

- Administer systemic antibiotics promptly (e.g., cefazolin, 1 g i.v. q8h, for clean, inert objects). If the object is contaminated or organic, treat as orbital cellulitis (see 7.3.1, ORBITAL CELLULITIS).

- Follow vision, degree (if any) of afferent pupillary defect, extraocular motility, proptosis, and eye discomfort daily.

- Surgical exploration and removal of the foreign body when indicated (as above). Discuss with the patient and family preoperatively that successful retrieval may be impossible. Wood often splinters, and multiple procedures may be necessary to entirely remove it. Organic foreign bodies frequently cause recurrent or smoldering infection that may require months of antibiotic therapy and additional surgical exploration. This may result in progressive orbital soft tissue fibrosis and restrictive strabismus.

- If the decision is made to leave the orbital foreign body in place, discharge when stable with oral antibiotics (e.g., amoxicillin–clavulanate 250/125 to 500/125 mg p.o. q8h or 875/125 mg p.o. b.i.d.) to complete a 10- to 14-day course.

- Patients with small inorganic foreign bodies not requiring surgical intervention may be discharged without hospitalization with oral antibiotics for a 10- to 14-day course.

Posteriorly located, inorganic foreign bodies are often simply observed if inert and not causing optic nerve compression because of the risk of iatrogenic optic neuropathy or diplopia if surgical removal is attempted. Alternatively, even an inert and otherwise asymptomatic metallic foreign body that is anterior and easily accessed may be removed with relatively low morbidity. |

If the foreign body is located in the posteromedial orbit, removal may be best achieved from an endonasal approach. Consider ENT and/or neurosurgical consultation and CT protocols for image-guided surgery when appropriate. |

Follow Up

The patient should return within 1 week of discharge (or immediately if the condition worsens). Close follow up is indicated for several weeks after the antibiotic is stopped to assure that there is no clinical evidence of infection or migration of the orbital foreign body toward a critical orbital structure (e.g., the optic nerve, EOM, globe). Reimage patient as clinically necessary. See 3.14, RUPTURED GLOBE AND PENETRATING OCULAR INJURY; 3.11, TRAUMATIC OPTIC NEUROPATHY; and 7.3.1, ORBITAL CELLULITIS.