Blurred vision, floaters, ocular pain, and photophobia. Affected patients are usually immunocompetent.

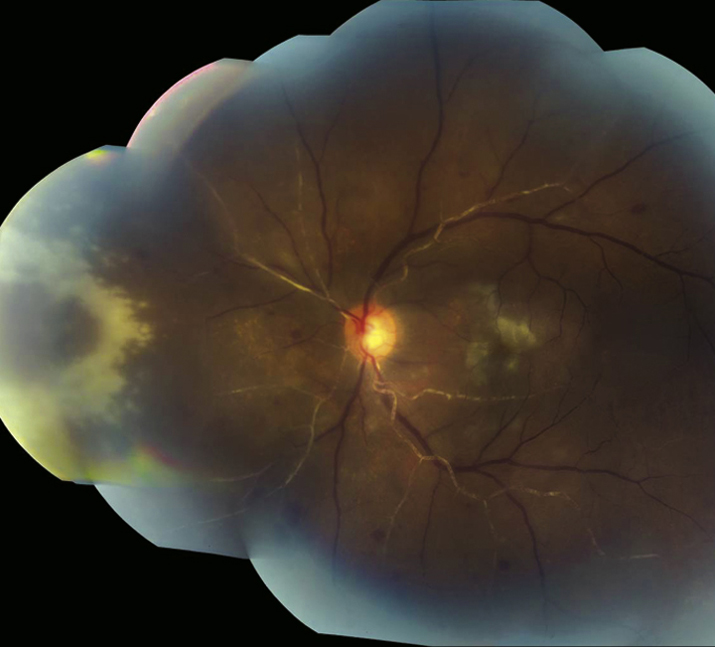

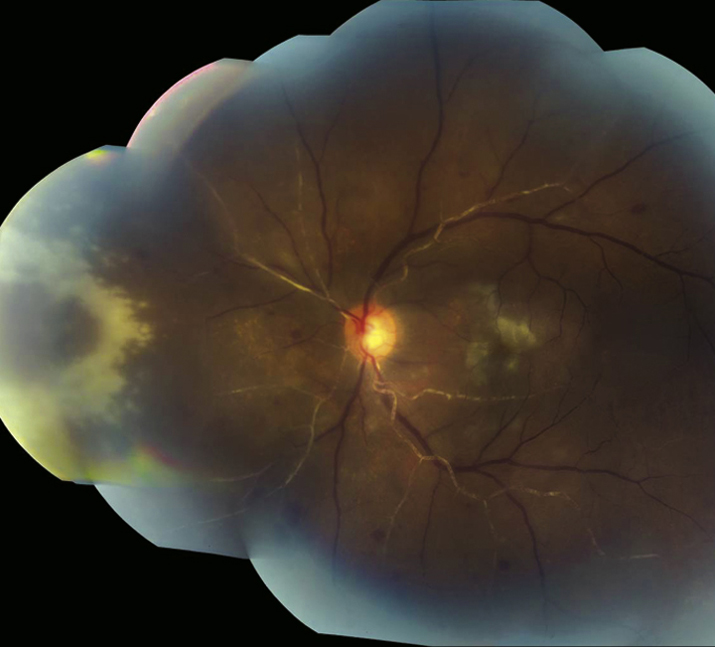

(See Figure 12.8.1.)

Critical

The American Uveitis Society criteria include one or more foci of retinal necrosis with discrete borders in the peripheral retina, rapid progression of disease in the absence of antiviral therapy, circumferential spread, evidence of occlusive vasculopathy with arterial involvement, and prominent inflammatory reaction in the anterior chamber and vitreous. If untreated, the circumferential progression of necrosis may become confluent and spread posteriorly. The macula is typically spared early in the disease course.

Other

Anterior chamber reaction; KP; conjunctival injection; episcleritis or scleritis; increased IOP; sheathed retinal arterioles and sometimes venules, especially in the periphery; retinal hemorrhages (minor finding); optic disc edema; delayed RRD occurs in approximately 70% of patients secondary to large irregular posterior breaks. Usually begins unilaterally but may involve the second eye in one-third of cases within weeks to months. An optic neuropathy with disc edema or pallor sometimes develops.

12-8.1 Acute retinal necrosis.

See 12.3, POSTERIOR UVEITIS.

- CMV retinitis (Table 12.8.1).

- PORN: Rapidly progressive retinitis characterized by clear vitreous and sheet-like opacification deep to normal-looking retinal vessels, and occasional spontaneous vitreous hemorrhage. PORN is usually found in immunocompromised individuals and frequently leads to rapid bilateral blindness due either to the infection itself or to secondary retinal detachment, making prompt diagnosis and treatment essential. Unlike ARN, pain and vitritis are minimal and macular involvement occurs early.

- Syphilis.

- Toxoplasma chorioretinitis.

- Behçet disease.

- Sarcoidosis.

- Fungal or bacterial endophthalmitis.

- Large cell lymphoma. Consider in patients >50 years of age with refractory unilateral vitritis, yellow-white subretinal infiltrates, and absence of pain.

ARN is a clinical syndrome caused by the herpes virus family: VZV (older patients), HSV (younger patients), or rarely, CMV or Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

WorkupSee 12.3, POSTERIOR UVEITIS, for a nonspecific uveitis workup.

- History: Risk factors for AIDS or other immunocompromised states (iatrogenic, autoimmune, malignancy, or genetic)? If yes, the differential diagnosis includes CMV retinitis and PORN. Ask about history of shingles (especially zoster ophthalmicus) or herpes simplex infections. Head trauma (including neurosurgery) and ocular surgery may precipitate ARN. Rarely, ARN can follow periocular or intravitreal corticosteroid injections. Most patients have no identifiable precipitating factors.

- Complete ocular examination: Evaluate the anterior chamber and vitreous for cells, measure IOP, and perform a dilated retinal examination using indirect ophthalmoscopy; gentle scleral depression as necrotic retina has an increased risk of retinal detachment.

- Consider a CBC with differential, RPR or VDRL, FTA-ABS or treponemal-specific assay, ESR, Toxoplasma titers, PPD or IGRA, and chest radiograph or CT to rule out other etiologies.

- Consider HIV testing.

- Anterior chamber paracentesis for herpes virus and Toxoplasma PCR to confirm the causative virus is highly specific but sensitivity may vary. See Appendix 13, ANTERIOR CHAMBER PARACENTESIS.

- Consider IVFA to identify retinal vasculitis and areas of ischemia.

- MRI of the brain and orbits in cases of suspected optic nerve dysfunction.

- CT or MRI of the brain and lumbar puncture if large cell lymphoma, tertiary syphilis, or encephalitis is suspected.