Decreased vision, photophobia, pain, and red eyes; accompanied or preceded by a headache, stiff neck, nausea, vomiting, fever, and malaise. Hearing loss, noise causing ear pain, and tinnitus frequently occur. Typically bilateral.

NOTE: NOTE: |

Harada disease refers to isolated ocular findings without associated systemic signs of VKH syndrome. |

Diagnostic criteria include the following:

- (1) no history of ocular trauma, (2) no evidence of other disease processes, (3) bilateral anterior or panuveitis, (4) neurologic/auditory findings (usually occur before ocular disease), and (5) dermatologic findings (usually occur after ocular disease).

- Complete VKH includes criteria 1 to 5, incomplete VKH includes criteria 1 to 3 and either 4 or 5, and probable VKH (isolated ocular disease) includes criteria 1 to 3.

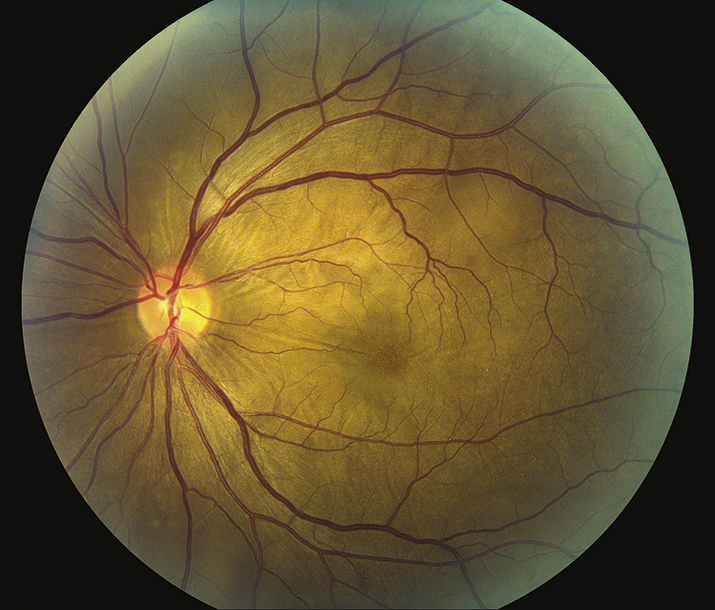

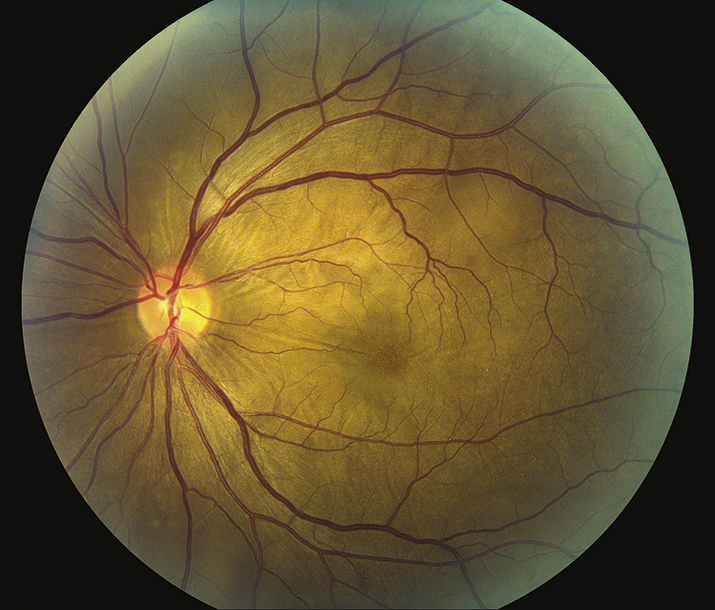

(See Figure 12.11.1.)

Critical

- Anterior: Anterior chamber flare and cells, granulomatous (mutton-fat) KP, perilimbal vitiligo (e.g., depigmentation around the limbus).

- Posterior: Bilateral serous retinal detachments with underlying choroidal thickening, vitreous cells, opacities, and optic disc edema.

- Systemic (four phases):

- Prodromal: loss of high-frequency hearing, tinnitus, meningismus, encephalopathy, and hypersensitivity of the skin to touch.

- Uveitic: acute ocular findings (see preceding bullets).

- Convalescent: alopecia, vitiligo, poliosis, “sunset glow” fundus (yellow-orange appearance of the fundus due to depigmentation of the RPE and choroid).

- Chronic recurrent: recurrence of anterior uveitis, subretinal fibrosis, neovascularization, glaucoma, and cataract.

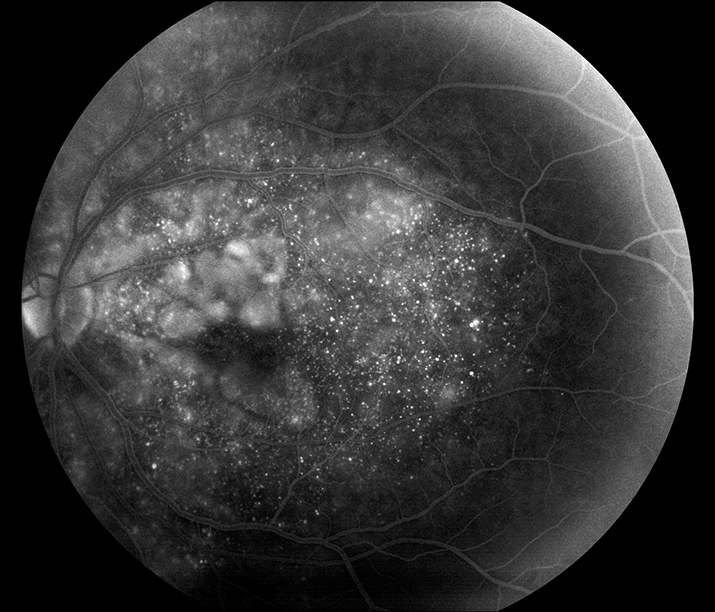

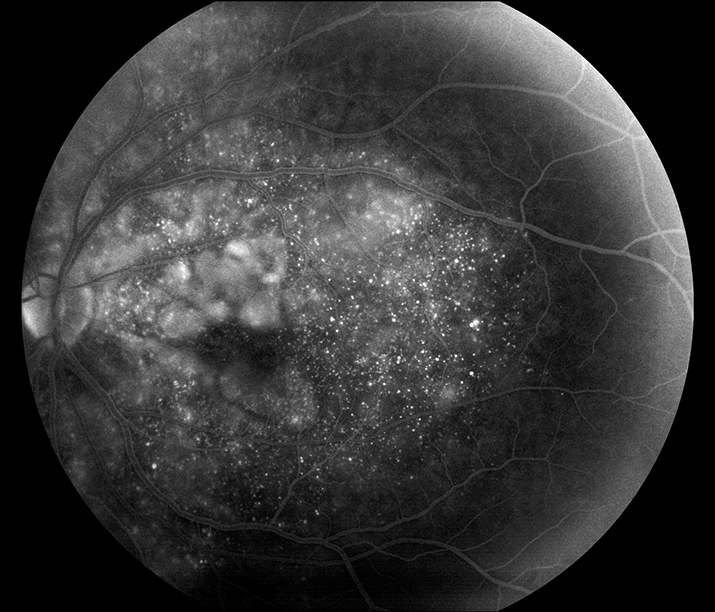

- IVFA: Multiple pinpoint leaking areas of hyperfluorescence at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium (see Figure 12.11.2).

12-11.2 IVFA of VKH.

Other

- Anterior: Iris nodules, peripheral anterior or posterior synechiae, scleritis, hypotony, or increased IOP from the forward rotation of ciliary processes.

- Posterior: Sunset glow fundus (mottling and atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium after the serous retinal detachment resolves), retinal vasculitis, choroidal neovascularization, and chorioretinal scars.

- Systemic: Neurologic signs, including loss of consciousness, paralysis, and seizures.

12-11.1 Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada (VKH) disease.

Epidemiology

Typically, patients are aged 20 to 50 years, female (77%), and have pigmented skin (especially Asian, Middle Eastern, Hispanic, or Native American).

See Table 12.11.1 for the differential of serous retinal detachments and 12.3, POSTERIOR UVEITIS. In particular, consider the following:

- Sympathetic ophthalmia: History of trauma or surgery (especially repeated vitreoretinal procedures) in the contralateral eye. Usually no systemic signs. See 12.18, SYMPATHETIC OPHTHALMIA.

- APMPPE: Ophthalmoscopic and IVFA features may be very similar, but there is less vitreous inflammation and no anterior segment involvement. See 12.3, POSTERIOR UVEITIS.

- Posterior scleritis: Typically unilateral, not typically associated with neurologic or dermatologic findings. Associated with an ultrasonographic “T” sign.

- Systemic arterial hypertension and pregnancy-related hypertension: Acute elevation in blood pressure can produce multifocal serous retinal detachments.

- Other granulomatous panuveitides (e.g., syphilis, sarcoidosis, and tuberculosis).

12-11.1 Differential Diagnosis of Serous Retinal Detachments

| Harada Disease | | Malignant hypertension | | Toxemia of pregnancy | | Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy | | Idiopathic uveal effusion syndrome | | Sympathetic ophthalmia | | Posterior scleritis | | Central serous chorioretinopathy | | Choroidal tumors (including metastases) | | Choroidal neovascularization | | Congenital optic disc pit | | Nanophthalmos |

|

WorkupSee 12.3, POSTERIOR UVEITIS, for a nonspecific uveitis workup.

- History: Neurologic symptoms, hearing loss, or hair loss? Previous eye surgery or trauma?

- Complete ocular examination, including a dilated retinal evaluation.

- CBC, RPR or VDRL, FTA-ABS or treponemal-specific assay, ACE, PPD or IGRA, blood pressure, and possibly chest radiograph or CT to rule out similar-appearing disorders.

- Consider B-scan ultrasonography to rule out posterior scleritis.

- Consider a CT or MRI of the brain with or without contrast in the presence of neurologic signs to rule out a CNS disorder.

- Lumbar puncture during attacks with meningeal symptoms for cell count and differential, protein, glucose, VDRL, Gram and methenamine–silver stains, and culture. CSF pleocytosis is often seen in VKH and APMPPE.

- Consider IVFA to evaluate for pinpoint leaking areas of hyperfluorescence at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium.

Inflammation is initially controlled with steroids; the dose depends on the severity of the inflammation. In moderate to severe cases, the following regimen can be used. Steroids are tapered very slowly as the condition improves.

- Topical steroids (e.g., prednisolone acetate 1% q1h).

- Systemic steroids (e.g., prednisone 60-80 mg p.o. daily or intravenous methylprednisolone sodium succinate 1 g daily for 3 days followed by oral therapy) with concurrent calcium/vitamin D supplementation and antiulcer prophylaxis.

- Topical cycloplegic (e.g., cyclopentolate 1% t.i.d. or atropine 1% b.i.d.).

- Treatment of any specific neurologic disorders (e.g., seizures or coma).

- For patients who cannot tolerate or are unresponsive to long-term oral steroids, consider immunosuppressive agents (e.g., antimetabolites, calcineurin inhibitors, cytotoxic agents, and TNF-alpha inhibitors).

- Initial management may require hospitalization if intravenous corticosteroids are initiated.

- Weekly, then monthly re-examination is performed, watching for recurrent inflammation and increased IOP.

- Steroids are tapered very slowly, and most patients should be transitioned to steroid-sparing immunosuppressants for long-term management. Inflammation may recur up to 9 months after the steroids have been discontinued. If this occurs, steroids should be reinstituted.

Autoimmune disease featuring inflammation of melanocyte-containing tissues.