Usually asymptomatic until the later stages. Symptoms may include visual field defects. Usually bilateral, but can present asymmetrically. Severe field damage and loss of central fixation typically do not occur until late in the disease.

Intraocular pressure (IOP): Although many patients will have an elevated IOP (normal range of 10 to 21 mm Hg), nearly half have an IOP of 21 mm Hg or lower at any one screening.

Gonioscopy: Anterior chamber angle open to scleral spur. No peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS).

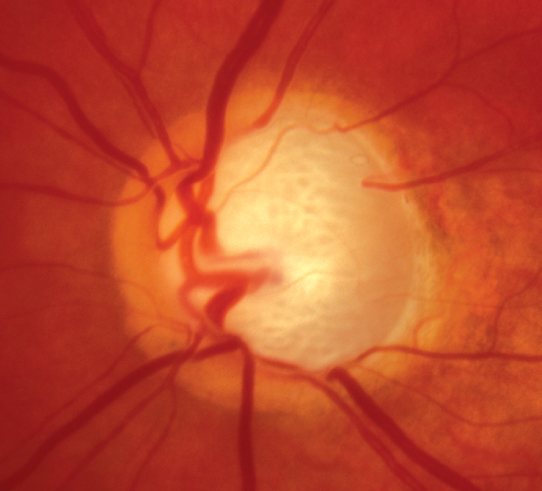

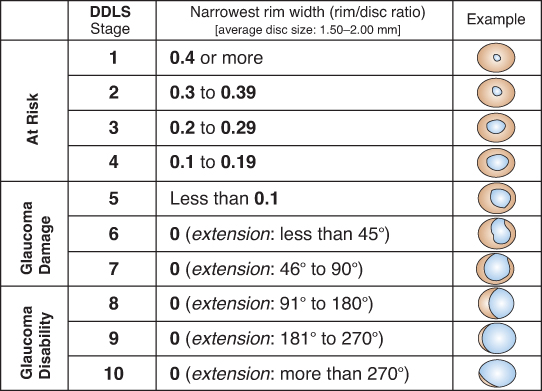

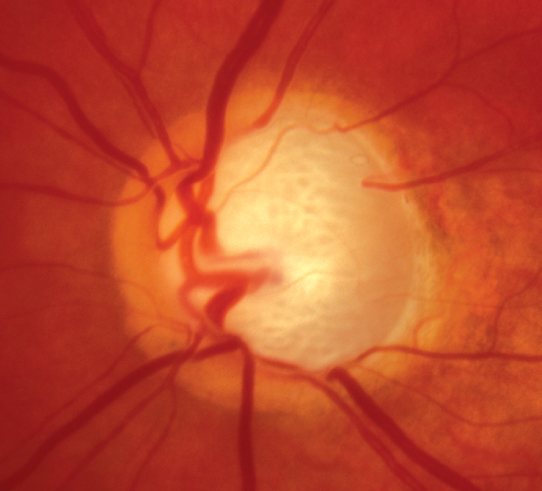

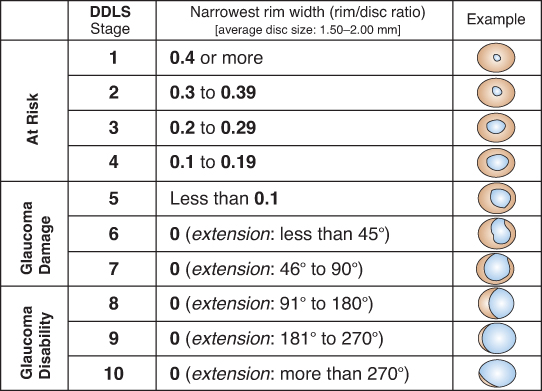

Optic nerve: See Figure 9.1.1. Characteristic appearance includes loss of rim tissue (includes notching; increased and/or progressive thinning most commonly inferiorly followed by superiorly, more rarely nasally or temporally), cupping, nerve fiber layer (NFL) defect, splinter or NFL hemorrhage that crosses the disc margin (Drance hemorrhage), acquired pit, cup/disc (C/D) asymmetry >0.2 in the absence of a cause (e.g., anisometropia, different nerve sizes), bayoneting (sharp angulation of the blood vessels at the cupped border), enlarged C/D ratio (>0.6; less specific), progressive enlargement of the cup, and greater disc damage likelihood scale (DDLS) score (See Figure 9.1.2).

Figure 9.1.1: Primary open-angle glaucoma with advanced optic nerve cupping.

Figure 9.1.2: Disc damage likelihood scale (DDLS).

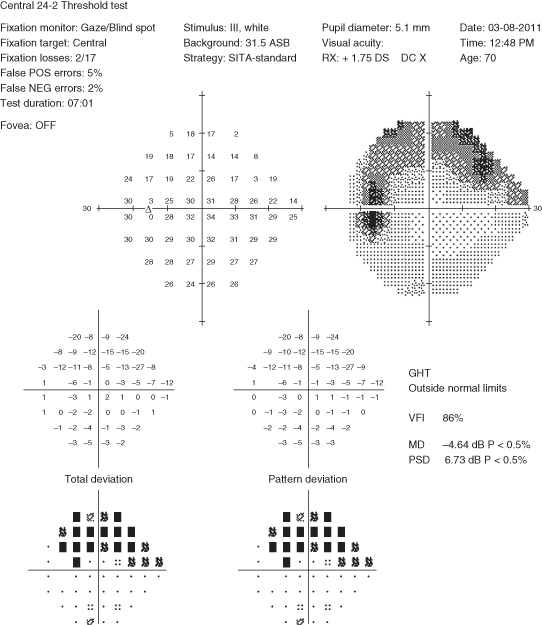

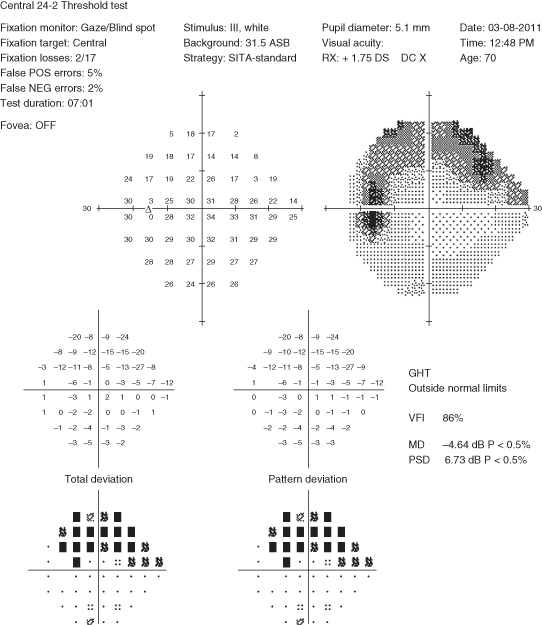

Visual fields: Characteristic visual field loss patterns include nasal step, paracentral scotoma, arcuate scotoma extending from the blind spot nasally (defects usually respect the horizontal midline or are greater in one hemifield than the other), altitudinal defect, generalized depression, or temporal wedge (rare) (See Figure 9.1.3).

Figure 9.1.3: Humphrey visual field showing a superior arcuate defect or scotoma of the left eye.

Other

Large fluctuations in IOP, inter-eye IOP asymmetry >5 mm Hg, β-zone peripapillary atrophy, absence of microcystic corneal edema, and absence of secondary features (e.g., pseudoexfoliation, inflammation, pigment dispersion).

If anterior chamber angle is open on gonioscopy:

Ocular hypertension: Normal optic nerve and visual field. See 9.3, Ocular Hypertension.

Physiologic optic nerve cupping: Static enlarged C/D ratio without rim notching, NFL thinning or visual field loss. Usually, normal IOP and large optic nerve (>about 2 mm). Often familial.

Secondary open-angle glaucoma: Identifiable cause for open-angle glaucoma including inflammatory, exfoliative, pigmentary, steroid-induced, angle recession, traumatic (as a result of direct injury, blood, or debris), and glaucoma related to increased episcleral venous pressure (e.g., Sturge–Weber syndrome, carotid–cavernous fistula), intraocular tumors, degenerated red blood cells (ghost cell glaucoma), lens-induced, degenerated photoreceptor outer segments following chronic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (Schwartz–Matsuo syndrome), or developmental anterior segment abnormalities.

Low-tension glaucoma: Same as primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) except normal IOP. See 9.2, Low-Tension Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma (Normal Pressure Glaucoma).

Previous glaucomatous damage (e.g., from steroids, uveitis, glaucomatocyclitic crisis, trauma) in which the inciting agent has been removed. Nerve appearance now static.

Optic atrophy: Characterized by disproportionally more optic nerve pallor than cupping. IOP usually normal unless a secondary or unrelated glaucoma is present. Color vision and central vision are often decreased, although not always. Causes include tumors of the optic nerve, chiasm, or tract; syphilis, ischemic optic neuropathy, drugs, retinal vascular or degenerative disease, and others. Visual field defects that respect the vertical midline are typical of intracranial lesions localized at the chiasm or posterior to it.

Congenital optic nerve defects (e.g., colobomas, optic nerve pits): Visual field defects may be present but are static.

Myopia: Discs may be tilted and difficult to assess. Can be associated with static visual field defects including an enlarged blind spot.

Optic nerve drusen: Optic nerves not usually cupped and drusen often visible. Visual field defects may remain stable or progress unrelated to IOP. The most frequent defects include arcuate defects or an enlarged blind spot. Characteristic calcified lesions can be seen on B-scan ultrasound (US) (as well as on computed tomography [CT]). Autofluorescence can also highlight nerve drusen.

If anterior chamber angle is closed or partially closed on gonioscopy:

History: Presence of risk factors (family history of blindness or visual loss from glaucoma, older age, African descent, diabetes, myopia, hypertension, or hypotension)? Previous history of increased IOP, chronic steroid use, or ocular trauma? Refractive surgery including laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) in past (i.e., change in pachymetry)? Review of past medical history to determine appropriate therapy including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure, heart block or bradyarrhythmia, renal disease, allergies?

Baseline glaucoma evaluation: All patients with suspected glaucoma of any type should have the following:

Complete ocular examination including visual acuity, pupillary assessment for a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD), visual fields, slit-lamp examination, applanation tonometry, gonioscopy, and dilated fundus examination (if the angle is open) with special attention to the optic nerve. Color vision testing is indicated if any suspicion of a neurologic disorder or optic neuropathy.

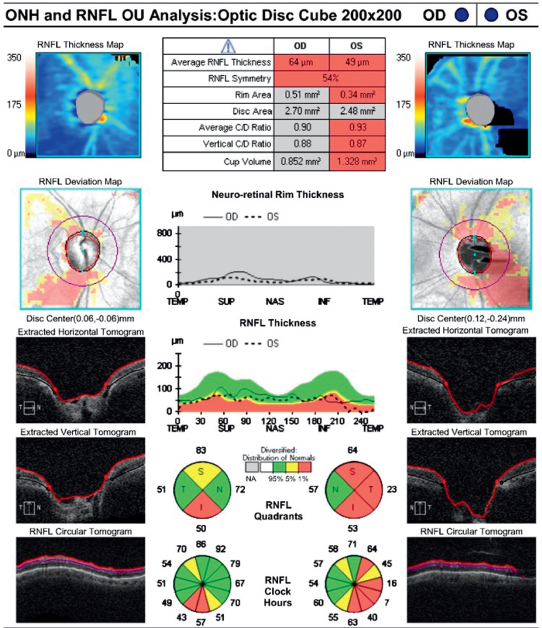

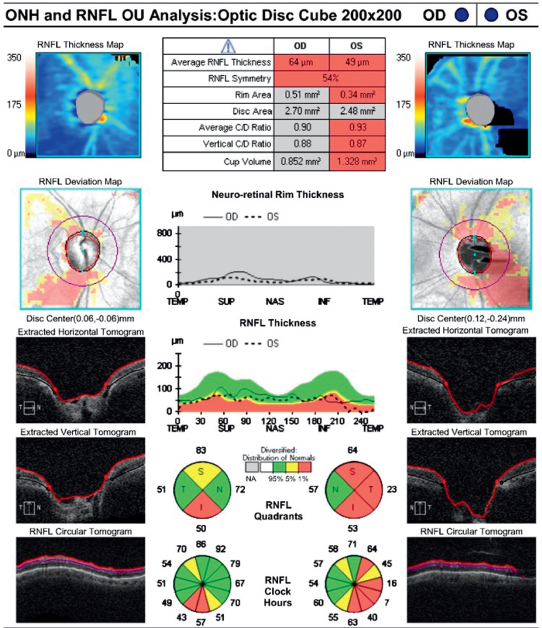

Baseline documentation of the optic nerves. May include DDLS score, meticulous drawings, stereoscopic disc photos, red-free photographs, and/or computerized image analysis (e.g., optical coherence tomography [OCT] with analysis of the NFL and ganglion cell layer or Heidelberg retina tomography [HRT]) (See Figure 9.1.4). Documentation should include presence or absence of pallor and/or disc hemorrhages.

Figure 9.1.4: Optical coherence tomography of the optic nerve head (ONH) and retinal nerve fiber layer (NFL) thickness.

Formal visual field testing (e.g., Humphrey or Octopus automated visual field). Goldmann visual field tests may be helpful in patients unable to take the automated tests adequately. Standard visual field testing includes evaluation of peripheral and central field (e.g., Humphrey 24–2). In cases of paracentral defect or advanced disease, specialized central field testing (e.g., Humphrey 10–2) is recommended.

Measure central corneal thickness (CCT). Corneal thickness variations affect apparent IOP as measured with applanation tonometry. Average corneal thickness is 535 to 545 microns. Thinner corneas tend to underestimate IOP, whereas thicker corneas tend to overestimate IOP. A thin CCT is an independent risk factor for the development of POAG. Of note, corneal refractive surgery (e.g., LASIK, photorefractive keratectomy [PRK], small incision lenticule extraction [SMILE]) can decrease CCT, leading to IOP underestimation. Consider checking the cornea compensated IOP and corneal biomechanical characteristics in those with thin or ectatic corneas (e.g., using the Ocular Response Analyzer [ORA] or Corvis ST).

Evaluation for other causes of optic nerve damage should be considered when any of the following atypical features are present:

Optic nerve pallor out of proportion to the degree of cupping.

Visual field defects greater than expected based on amount of cupping.

Visual field patterns not typical of glaucoma (e.g., defects respecting the vertical midline, congruous defects, enlarged blind spot, central scotoma).

Unilateral progression despite equal IOP in both eyes.

Decreased visual acuity out of proportion to the amount of cupping or field loss.

Color vision loss, especially in the red–green axis.

If any of these are present, further evaluation may include:

History: Acute episodes of eye pain or redness? Steroid use? Acute visual loss? Ocular trauma? Surgery, systemic trauma, heart attack, dialysis, or other event that may lead to hypotension, episode of significant blood loss?

Diurnal IOP curve consisting of multiple IOP checks throughout the day in-office or using home tonometry.

Consider other laboratory workup for nonglaucomatous optic neuropathy: Heavy metals, vitamin B12/folate, angiotensin-converting enzyme, antinuclear antibody, Lyme antibody, rapid plasma reagin or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory, and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption or other treponemal-specific tests. If giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a consideration, check erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and platelets (see 10.17, Arteritic Ischemic Optic Neuropathy [Giant Cell Arteritis]).

In cases where a neurologic disorder is suspected, obtain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbits with gadolinium and fat suppression if no contraindications present.

Check blood pressure, fasting blood sugar, hemoglobin A1c, lipid panel, and CBC (screening for anemia). Refer to an internist for a complete cardiovascular evaluation.

General Considerations

Who to treat?

The decision to treat must be individualized. Some general guidelines are suggested.

Is a glaucomatous process present?

Glaucomatous damage is likely if any of the following are present: presence of thin or notched optic nerve rim, characteristic visual field loss, retinal NFL damage, or if DDLS score is >5 (see Figure 9.1.2). Treatment should be considered in the absence of manifest damage if IOP is higher than 30 mm Hg, and/or IOP asymmetry is more than 6 mm Hg.

Is the glaucomatous process active?

Determine the rate of damage progression by careful follow-up. Certain causes of optic nerve rim loss may be static (e.g., prior steroid response). Disc hemorrhages suggest active disease.

Is the glaucomatous process likely to cause disability?

Consider the patient’s age, overall physical and social health, as well as an estimation of his or her life expectancy.

What is the treatment goal?

The goal of treatment is to enhance or maintain the patient’s health by halting optic nerve damage while avoiding undue side effects of treatment. The only proven method of stopping or slowing optic nerve damage is reducing IOP. Reduction of IOP by at least 30% appears to have the best chance of preventing further optic nerve damage. An optimal goal may be to reduce the IOP at least 30% below the threshold of progression. If damage is severe or progressive, greater reduction in IOP may be necessary.

How to treat?

The main treatment options for glaucoma include medications, laser trabeculoplasty (LT) (selective [SLT] more commonly than argon [ALT]), and glaucoma surgery. Medications or LT are appropriate initial therapies. Based on the Laser in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension (LiGHT) Trial, initial LT may reduce the risk of disease progression and need for incisional surgery compared to initial drop therapy. LT should be especially considered in patients at risk for poor adherence or with medication side effects. Surgery may be an appropriate initial treatment if damage is advanced or in the setting of a rapid rate of progression. Options include glaucoma filtering surgery (e.g., trabeculectomy, tube shunt), minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS), laser cyclophotocoagulation of the ciliary body (e.g., with diode laser or endolaser), and cyclocryotherapy. Surgery should always be considered for any patient with advanced/progressive disease or IOP uncontrolled by other methods.

|

NOTE NOTEMIGS encompasses newer surgical options that offer the advantages of shorter healing times and potentially fewer complications. MIGS is generally considered for patients with mild-to-moderate glaucoma. Some MIGS procedures include trabecular micro-bypass devices, canaloplasty, goniotomy, subconjunctival microstents, and cyclophotocoagulation. |

Medications

Unless there are extreme circumstances (e.g., IOP >35 mm Hg or impending loss of central fixation), treatment is often started by using one type of drop with reexamination in 1 to 6 weeks (depending on IOP and individualized risk factors) to check for efficacy.

Prostaglandin agonists (e.g., latanoprost 0.005% q.h.s., bimatoprost 0.01% or 0.03% q.h.s., travoprost 0.004% q.h.s., tafluprost 0.0015% q.h.s. [preservative free]) are to be used with caution in patients with active uveitis or cystoid macular edema (CME) or a history of ocular herpes simplex virus (HSV), and are contraindicated in pregnant women. Inform patients of potential pigment changes in iris and periorbital skin, as well as hypertrichosis. Irreversible iris pigment changes rarely occur in blue or dark brown eyes; those at highest risk for iris hyperpigmentation have hazel, gray irides.

β-Blockers (e.g., levobunolol or timolol 0.25% to 0.5% daily or b.i.d.) should be avoided in patients with asthma, COPD, heart block, bradyarrhythmia, unstable congestive heart failure, depression, or myasthenia gravis. In addition to bronchospasm and bradycardia, other side effects include hypotension, decreased libido, central nervous system (CNS) depression, and reduced exercise tolerance.

Selective α2-receptor agonists (e.g., brimonidine 0.1%, 0.15%, or 0.2% b.i.d. to t.i.d.) are contraindicated in patients taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (risk of hypertensive crisis) and relatively contraindicated in children under the age of 5 (risk for cardiorespiratory and CNS depression). See 8.13, Congenital/Infantile Glaucoma. Apraclonidine 0.5% or 1% is rarely used due to tachyphylaxis and high allergy rate but may be used for short-term therapy (3 months).

Topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs) (e.g., dorzolamide 2% or brinzolamide 1% b.i.d. to t.i.d.) should be avoided, but are not contraindicated, in patients with sulfa allergy. These medications theoretically could cause the same side effects as systemic CAIs, such as metabolic acidosis, hypokalemia, gastrointestinal symptoms, weight loss, paresthesia, and aplastic anemia. However, systemic symptoms from topical CAIs are extremely rare. There have been no reported cases of aplastic anemia from topical use. Corneal endothelial dysfunction may be exacerbated with topical CAIs; these medications should be used cautiously in patients with Fuchs corneal dystrophy and post keratoplasty.

Rho kinase inhibitors (e.g., ripasudil 0.4% b.i.d. and netarsudil 0.02% q.d.) commonly cause conjunctival hyperemia (50–60%). May cause subconjunctival hemorrhage, pruritus, superficial punctate keratitis, increased lacrimation, blepharitis, and decreased vision. Up to 25% of patients will have cornea verticillata after 1 year of use, although it is not visually significant and is reversible with discontinuation.

Miotics (e.g., pilocarpine q.i.d.) are usually used in low strengths initially (e.g., 1% to 2%) and then built up to higher strengths (e.g., 4%). Commonly not tolerated in patients <40 years because of accommodative spasm. Miotics are usually contraindicated in patients with retinal holes and should be used cautiously in patients at risk for retinal detachment (e.g., high myopia and aphakia).

|

NOTE NOTEPilocarpine is not routinely used due to its adverse side effect profile including associated increased risk for uveitis and retinal detachment, possibility for miosis-induced angle closure, and symptoms such as headache. |

Sympathomimetics (dipivefrin 0.1% b.i.d. or epinephrine 0.5% to 2.0% b.i.d.) rarely reduce IOP to the degree of the other drugs but have few systemic side effects (rarely, cardiac arrhythmias). They often cause red eyes and may cause CME in aphakic patients.

Systemic CAIs (e.g., methazolamide 25 to 50 mg p.o. b.i.d. to t.i.d., acetazolamide 125 to 250 mg p.o. b.i.d. to q.i.d., or acetazolamide 500 mg sequel p.o. b.i.d.) are relatively contraindicated in patients with renal failure. Potassium levels must be monitored if the patient is taking other diuretic agents or digitalis. Side effects such as fatigue, nausea, confusion, and paresthesias in the fingers and toes are common. Rare, but severe, hematologic side effects (e.g., aplastic anemia) and Stevens–Johnson syndrome have occurred. Allergy to sulfa drugs is not an absolute contraindication to the use of systemic CAIs, but extra caution should be exercised in monitoring for an allergic reaction. Intravenous forms of systemic CAIs (e.g., acetazolamide 250 to 500 mg i.v.) may be utilized if IOP reduction is urgent or if IOP is refractory to topical therapy. Consider checking baseline creatinine in patients with suspected or confirmed renal disease.

|

NOTE NOTEPatients should be instructed to press a fingertip into the inner canthus to occlude the punctum for 10 seconds after instilling a drop. Doing so will decrease systemic absorption. If unable to perform punctal occlusion, keeping the eyelids closed without blinking for 1 to 2 minutes after drop administration also reduces systemic absorption. |

Selective Laser Trabeculoplasty

Can be considered as first-line therapy in patients with OAG. Low dose energy (typically 0.3–1.4 mJ per shot) is applied to 180 to 360 degrees of the trabecular meshwork (TM). The LiGHT Trial reported nearly 70% of patients maintained an IOP below target with SLT alone. SLT can be repeated if initial treatment does not successfully lower IOP or the IOP lowering effects diminish over time. Consider treating only two quadrants at a time with lower energy in patients prone to IOP spikes (i.e. pigment dispersion).

Argon Laser Trabeculoplasty

ALT uses higher energy than SLT with more resultant tissue damage. Studies have shown an equivalent IOP-lowering effect with SLT and ALT. It has an initial success rate of 70% to 80%, dropping to 50% in 2 to 5 years.

Filtering Surgery

Trabeculectomy and tube-shunt surgery may obviate the need for medications. Adjunctive use of antimetabolites (e.g., mitomycin C, 5-fluorouracil) in trabeculectomy surgery may aid in the effectiveness of the surgery but increases the risk of complications (e.g., bleb leaks and hypotony).

GazzardG, KonstantakopoulouE, Garway-HeathD, et al.Laser in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension (LiGHT) Trial: six-year results of primary selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for the treatment of glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Ophthalmology. 2023;130:139–151.

KassMA, HeuerDK, HigginbothamEJ, et al.The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(6):701–713.