NEUROFIBROMATOSIS TYPE 1 (VON RECKLINGHAUSEN SYNDROME)

(See Table 13.11.1.)

TABLE 13.11.1: Diagnostic Criteria for Neurofibromatosis 1 and 2

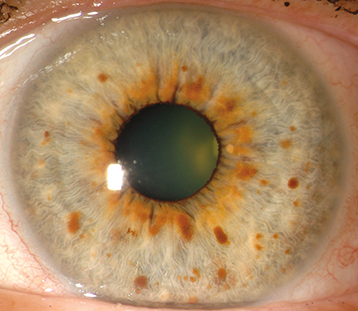

(See Figures 13.11.1 and 13.11.2.)

Lisch nodules, visual pathway glioma (12% to 15%), prominent corneal nerves, multifocal choroidal nevi, choroidal hamartoma (detectable by near-infrared high-frequency OCT), cranial nerve lesions (e.g., superior oblique palsy), glaucoma (usually associated with plexiform neuromas of the ipsilateral upper eyelid), pulsating proptosis secondary to absence of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone, ectropion uveae, and iris melanosis.

(See Table 13.11.1.)

Developmental delay, seizures, scoliosis, leukemia, juvenile xanthogranuloma, aortic and arteriovascular anomalies, and other cancers.

Autosomal dominant with variable expression: chromosome 17q11.2.

Family history. Examination of parents for Lisch nodules. If child is affected, consider further systemic and ocular evaluation.

MRI of the brain and orbits only if indicated by a sign or symptom, including ophthalmic findings of optic nerve dysfunction, optic nerve pallor/swelling/shunt vessels, or proptosis.

Dependent upon the findings. Every year up to 6 years old when risk of visual pathway glioma diminishes. Every 2 years thereafter. More frequent follow-up as needed for patients with gliomas or other signs of ophthalmic or orbital involvement, especially if risk factors for amblyopia (e.g., ptosis from plexiform neurofibroma).

NEUROFIBROMATOSIS TYPE 2

(See Table 13.11.1.)

Juvenile-onset posterior subcapsular cataracts, combined hamartoma of the RPE, epiretinal membrane, optic nerve sheath meningioma, and cranial nerve palsies.

Autosomal dominant with variable expression: chromosome 22q12.2.

Family history. If child is affected, consider further systemic and ocular evaluation.

Audiology and gadolinium-enhanced MRI of the brain and auditory canals should be performed.

STURGE–WEBER SYNDROME (LEPTOMENINGEAL ANGIOMATOSIS)

(See Figure 13.11.3.)

Diffuse choroidal hemangioma (“tomato catsup” fundus with uniform reddish background obscuring choroidal vasculature), glaucoma (increased risk with upper eyelid or combined upper and lower eyelid port-wine birthmark or choroidal hemangioma), iris heterochromia, blood in Schlemm canal seen on gonioscopy, and secondary serous retinal detachment. Ocular signs are all ipsilateral to port-wine birthmark.

Unilateral or bilateral (10%) port-wine birthmark (trigeminal nerve distribution patterns), developmental delay, seizures, ipsilateral facial hemihypertrophy, leptomeningeal angiomatosis, and cerebral calcifications.

Somatic mutation in GNAQ, extremely rare to transmit.

Complete general and ophthalmic examination with specific screenings for glaucoma and amblyopia. Periodic OCT macula if choroidal hemangioma present. Neuroimaging of the brain (CT or MRI).

Treat glaucoma if present. Early onset (<4 years old) usually caused by goniodysgenesis (see 8.13, Congenital/Infantile Glaucoma). Later onset usually caused by increased episcleral venous pressure. Presence of leptomeningeal angiomatosis is a relative contraindication to use of topical alpha-agonists.

Consider treating serous retinal detachment from underlying choroidal hemangioma. Laser photocoagulation success rate is low, but photodynamic therapy can be successful for smaller, circumscribed tumors. Low-dose radiotherapy using a plaque is often successful in leading to resolution of subretinal fluid.

Every 6 months or sooner for glaucoma screening and yearly for retinal examination with OCT.

TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS COMPLEX (BOURNEVILLE SYNDROME)

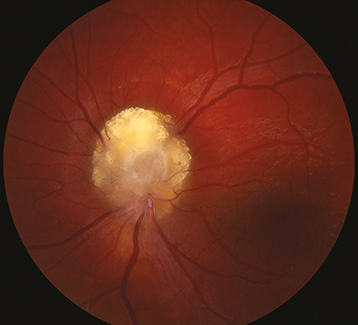

(See Figures 13.11.4 and 13.11.5.)

Astrocytic hamartoma of the retina or optic disc (a white, semitransparent, or mulberry-appearing tumor in the superficial retina that may undergo calcification with age; no prominent feeder vessels; no associated retinal detachment; often multifocal and bilateral) and punched-out chorioretinal depigmentation.

Adenoma sebaceum (yellow–red angiofibromas in a butterfly distribution on the upper cheeks), seizures, periventricular hamartomas, developmental delay, subungual angiofibromas, shagreen patches, ash leaf spots (hypopigmented skin lesions that illuminate with Wood lamp); renal cell carcinoma or angiomyolipoma; intracardiac rhabdomyoma or lipoma; pleural cysts and possible spontaneous pneumothorax; cystic bone lesions; and hamartomas of the liver, thyroid, pancreas, or testes.

Differential Diagnosis of Astrocytic Hamartoma

Retinoblastoma. See 8.1, Leukocoria.

Autosomal dominant with variable expression: TSC1 gene on chromosome 9q34 or TSC2 gene on chromosome 16p13.

Family history. Parents of affected child should first be evaluated by ocular and systemic examination/testing. If one parent is positive, then consider examination and testing of siblings of affected patient.

MRI of the brain and additional systemic testing as indicated by symptoms and signs or screening protocol.

Retinal astrocytomas usually require no treatment. Ophthalmic examination every 6 months to a 1 year after lesion is identified.

VON HIPPEL–LINDAU SYNDROME

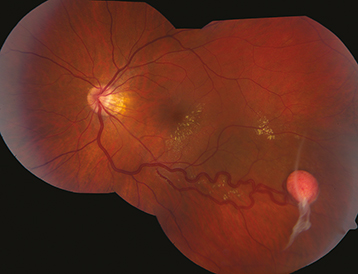

(See Figure 13.11.6.)

Retinal capillary hemangioma/hemangioblastoma (small, round, orange–red tumor with a prominent dilated feeding artery and draining vein), sometimes associated with subretinal exudates, subretinal fluid, and total retinal detachment. Bilateral in 50%. Can produce macular traction and epiretinal membrane. Peripheral lesions often present with macular exudates.

Central nervous system hemangioblastoma (cerebellum and spinal cord most common, 25% of cases), renal cell carcinoma, renal cysts, pheochromocytoma (possible malignant hypertension), pancreatic cysts, epididymal cystadenoma, endolymphatic sac tumor with hearing loss, and broad ligament tumors (females).

Autosomal dominant with variable expression: VHL gene on chromosome 3p26.

Differential Diagnosis of Retinal Hemangioblastoma

Coats disease: Aneurysmal dilation of blood vessels with prominent subretinal exudate and no identifiable tumor. See 8.1, Leukocoria.

Racemose hemangiomatosis: Large, dilated, tortuous vessels form arteriovenous communications void of intervening capillary beds without exudation or subretinal fluid.

Retinal cavernous hemangioma: Small vascular dilations (characteristic “cluster of grapes” appearance) around retinal vein without feeder vessels. Usually asymptomatic.

Retinal vasoproliferative tumor: Vascular tumor that appears as a yellow–red retinal mass, most commonly in the peripheral inferior retina of older patients. Visual loss usually associated with macular edema or epiretinal membrane. Feeder vessels can be slightly dilated and tortuous but not to the extent of retinal hemangioblastoma.

Retinal macrovessel: Large, solitary, nontortuous vessel without arteriovenous connection that supplies or drains the macular area and crosses the horizontal raphe. More commonly veins than arteries.

Congenital retinal vascular tortuosity: Tortuous retinal vessels without racemose component.

Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy: Bilateral, temporal, peripheral exudation with retinal vascular abnormalities and traction. See 8.3, Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy.

Systemic evaluation is indicated for all patients with retinal hemangioblastoma. Solitary tumors can occur without von Hippel–Lindau disease, but multiple or bilateral tumors are diagnostic of von Hippel–Lindau disease.

Family history. Begin with ocular examination of parents and consider systemic evaluation. If one parent is affected, then siblings of affected patients also need a full workup.

Young children may require examination under anesthesia to identify peripheral retinal tumors.

Periodic systemic evaluations for blood pressure measurements, urinary catecholamines, MRI brain, and abdominal US.

If retinal hemangioblastoma is affecting or threatening vision, laser photocoagulation, cryotherapy, transpupillary thermotherapy, photodynamic therapy with verteporfin, or radiotherapy is indicated depending on size of tumor. Studies are evaluating response with systemic HIF-2a inhibitors (e.g., Belzutifan).

Annual dilated fundus examination or more frequently based on findings.

WYBURN–MASON SYNDROME (RACEMOSE HEMANGIOMATOSIS)

(See Figure 13.11.7.)

Enormously dilated, tortuous retinal vessels with arteriovenous communications without communicating capillary beds and without mass or exudate. Rarely, proptosis from an orbital racemose hemangioma.

Midbrain racemose hemangiomas, intracranial calcification, seizures, hemiparesis, mental changes, facial nevi, and ipsilateral pterygoid fossa, mandibular, or maxillary hemangiomas.

Differential Diagnosis of Racemose Hemangiomas

See von Hippel–Lindau syndrome above.

Complete general and ophthalmic examinations, MRI of the brain, and orbital US.

No treatment is indicated for retinal lesions. Complications include blindness and rarely intraocular hemorrhage, retinal vascular obstruction, and neovascular glaucoma. Warn of hemorrhage risk with ipsilateral dental and facial surgery. Annual follow-up.

ATAXIA–TELANGIECTASIA (LOUIS–BAR SYNDROME)

Telangiectasias of the conjunctiva, horizontal or vertical oculomotor apraxia (inability to generate saccades, but normal pursuit), and cerebellar eye movements.

Progressive cerebellar ataxia with gradual deterioration of motor function. Cutaneous telangiectasias. Recurrent sinopulmonary infections. Various immunologic abnormalities (e.g., IgA deficiency and T-cell dysfunction). High incidence of malignancy (mainly leukemia or lymphoma), developmental delay and loss of motor milestones, vitiligo, premature graying of the hair, testicular or ovarian atrophy, hypoplastic or atrophic thymus, and acute radiosensitivity.

Autosomal recessive: ATM gene on chromosome 11q22.

No specific ocular treatment. Annual follow-up. Routine dermatology monitoring and full-thickness excision of lesions as needed.