Up to 50% of patients with scleritis have an associated systemic disease, typically connective tissue or vasculitic in nature. Workup indicated if no known underlying disease is present.

Connective tissue disease (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, relapsing polychondritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, reactive arthritis, polyarteritis nodosa, ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease), infectious (e.g., Pseudomonas, atypical mycobacteria, fungi, Nocardia, syphilis), trauma including status-post surgery (especially scleral buckle or pterygium surgery with mitomycin-C or beta irradiation), and gout.

Varicella zoster, tuberculosis, Lyme disease, other bacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas species with scleral ulceration, Proteus species associated with scleral buckle), sarcoidosis, foreign body, medications (e.g., pembrolizumab), or parasite.

Classification

Diffuse anterior scleritis: Widespread inflammation of the anterior segment.

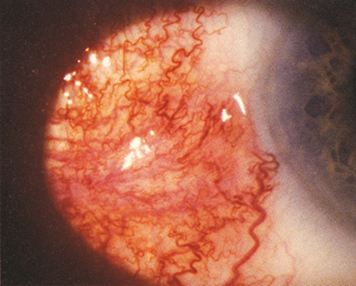

Nodular anterior scleritis: Immovable inflamed nodule(s) (see Figure 5.7.1).

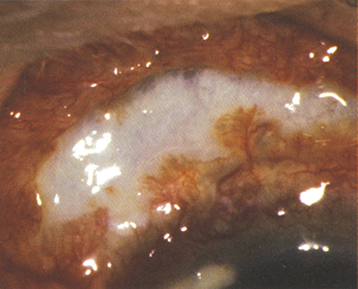

Necrotizing anterior scleritis with inflammation (see Figure 5.7.2): Extreme pain. The sclera becomes transparent (choroidal pigment visible) because of necrosis. High association with systemic inflammatory diseases.

Necrotizing anterior scleritis without inflammation (scleromalacia perforans): Typically asymptomatic. Seen most often in older women with long-standing rheumatoid arthritis.

Posterior scleritis: May start posteriorly, or rarely be an extension of anterior scleritis, or simulate an amelanotic choroidal mass. Associated with exudative retinal detachment, disc swelling, retinal hemorrhage, choroidal folds, choroidal detachment, restricted motility, proptosis, pain, or tenderness.