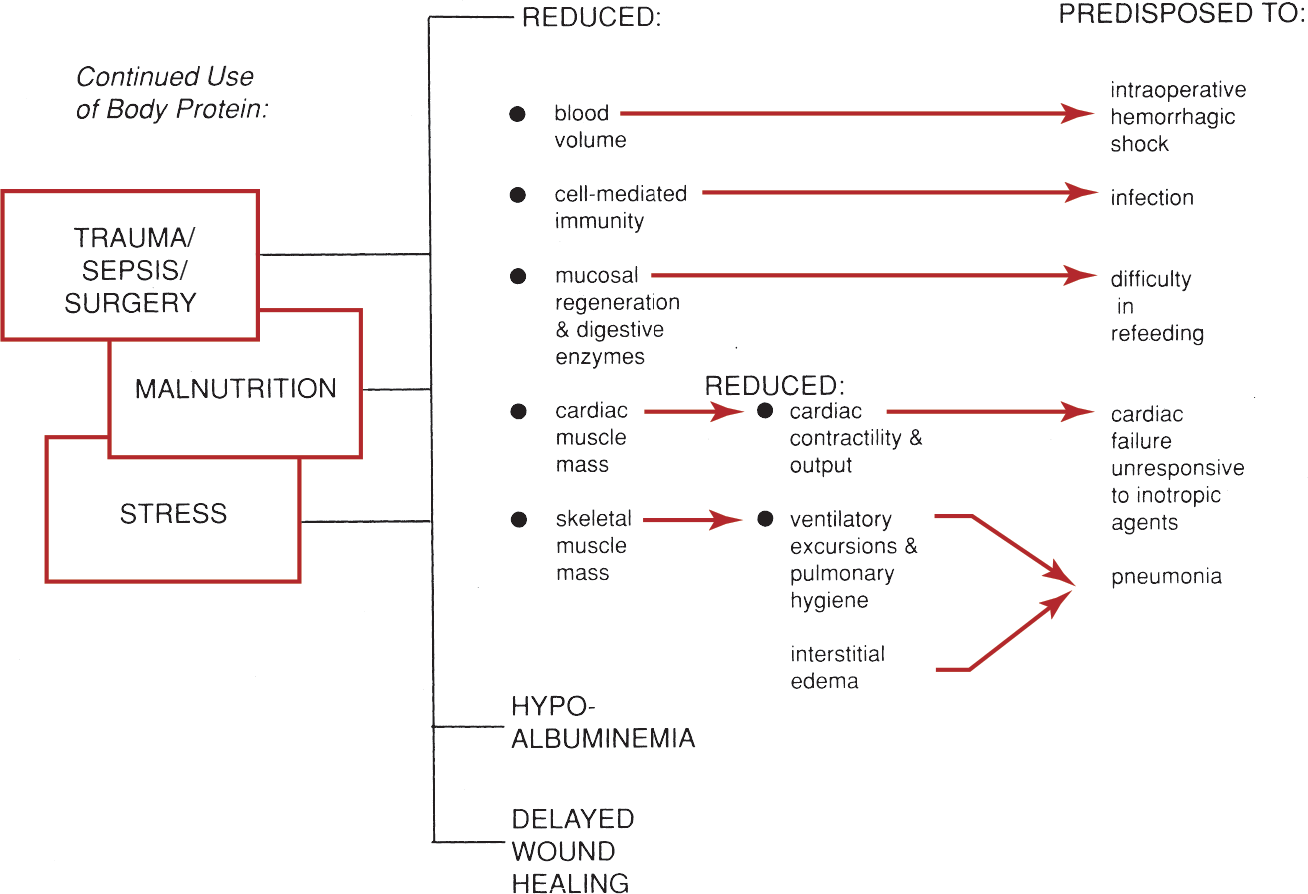

Patients who are candidates for nutritional support are those who suffer from a multiplicity of problems. Their clinical course is complicated by malnutrition and depletion of body protein (Fig. 12-1). Routes for delivery of nutritional support include the enteral and the intravenous (IV) routes.

The enteral route (i.e., tube feeding) is the preferred feeding route and is indicated for patients with a functional GI tract when oral nutrient intake is insufficient to meet needs (Doley & Phillips, 2017). Options for enteral access devices include nasoenteric tubes for short-term use and long-term devices such as gastrostomy, jejunostomy, and gastrojejunostomy tubes. In contrast to PN, enteral nutrition preserves the functional and structural integrity of the gut and maintains normal gallbladder function. Also, the gut-associated and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues are maintained. Immunoglobulin A (IgA) is secreted within the GI tract in response to nutrients, which prevents bacterial adherence (Doley & Phillips, 2017). An additional advantage to the enteral route is a lower cost compared with PN.

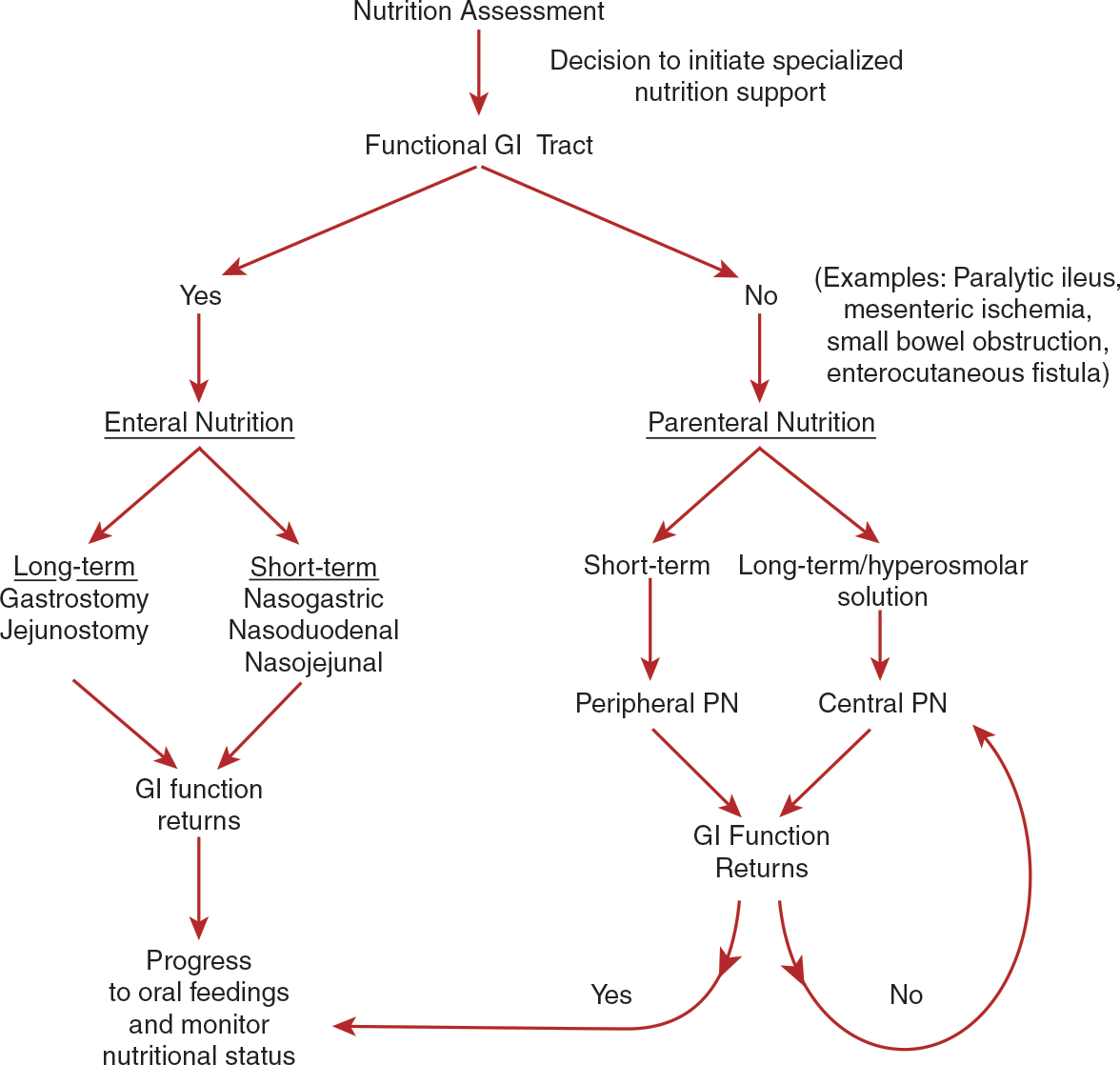

PN may be administered via the peripheral or central veins. Figure 12-2 shows an algorithm for determining the choice of nutritional support. PN is indicated for patients when the GI tract is not functional and in patients who cannot receive adequate nutrition via an oral diet or enteral nutrition (Ayers et al., 2020). PN may be given via a peripheral IV catheter (PIVC) for short-term administration (less than 2 weeks), or it may be given via a central vascular access device (CVAD) for longer term feeding, when peripheral access is limited, and/or when nutrient needs are large. PN is initiated in well-nourished stable adults who are not able to receive 50% or more of estimated nutritional requirements via the oral or enteral route after 7 days; if the patient is at nutritional risk, PN should be started within 3 to 5 days (Ayers et al., 2020). Examples of specific diagnoses associated with a need for PN include paralytic ileus, mesenteric ischemia, small-bowel obstruction, inflammatory bowel disease, congenital bowel defects, pancreatitis, hyperemesis gravidarum, and enterocutaneous fistulas.

Parenteral Nutrition and Cancer

Patients with GI cancers may suffer from digestive dysfunction or obstruction and toxicities associated with cancer treatment that result in weight loss and malnutrition. ASPEN (Worthington et al., 2017) provides recommendations for PN in palliative care, recommending that PN should not be used to treat poor oral intake and/or cachexia associated with advanced cancer, but rather should be limited to carefully selected patients with an expected survival of 2 to 3 months when oral intake or enteral feeding is not possible. Palliative care recommendations recommend PN only in carefully assessed patients with a good quality of life, a safe home environment, a life expectancy of at least several months, and when death is probable from starvation or malnutrition earlier than anticipated from disease progression alone (Mirhosseini & Fainsinger, 2015).