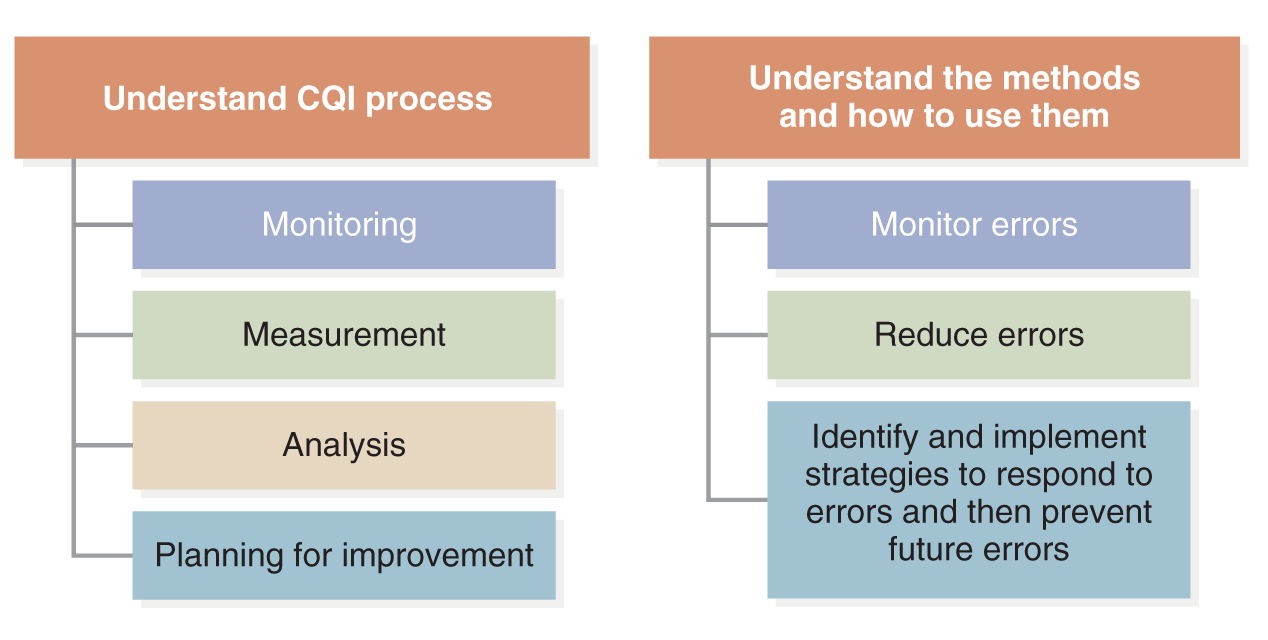

This chapter discusses the healthcare core competency: apply quality improvement (QI) and the related nursing competency on quality identified by the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN). The content in this chapter includes information about the key quality and associated safety reports (Quality Chasm series) and their recommendations. Accreditation of healthcare organizations (HCOs) is also related to the need to improve care. Nurses and nursing as a profession assume major roles in ensuring that care is safe and outcomes are reached, resulting in quality care. Appendix Ais an important resource for this content, providing additional content and terminology to assist in a greater understanding of quality health care. Continuous quality improvement (CQI) requires an effective use of a process as discussed in this chapter. Figure 12-1 provides an overview of the process and introduction to this content.

Figure 12-1 Continuous quality improvement: How do we do this?

A diagram illustrates the steps for continuous quality improvement.

The left side focuses on understanding the C Q I process, which includes monitoring, measurement, analysis, and planning for improvement. The right side focuses on understanding the methods and how to use them, which includes monitoring errors, reducing errors, and identifying and implementing strategies to respond to errors and prevent future errors.

The Core Competency: Apply Quality Improvement

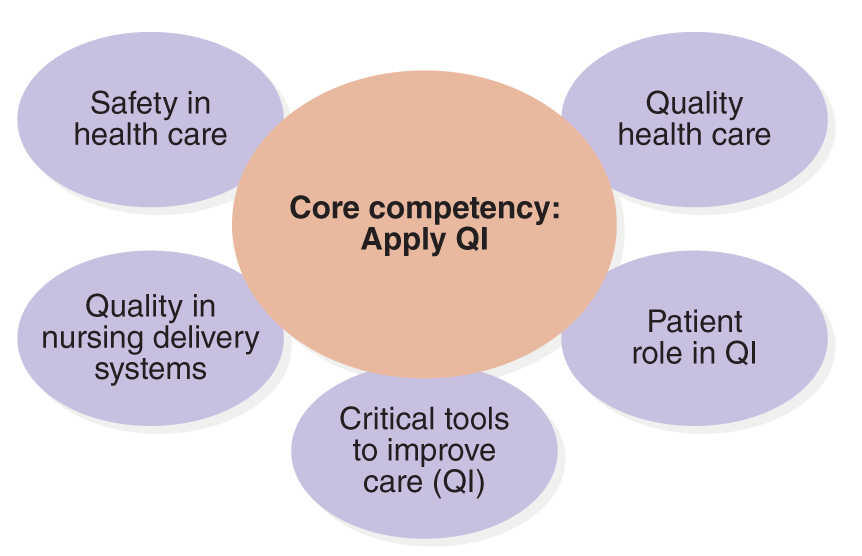

The competency focuses on applying QI, described as follows: “Identify errors and hazards in care; understand and implement basic safety design principles, such as standardization and simplification; continually understand and measure quality of care in terms of structure, process, and outcomes in relation to patient and community needs; and design and test interventions to change processes and systems of care, with the objective of improving quality” (IOM, 2003, p. 4) and relates to the QSEN (2022) competencies. Figure 12-2 identifies the key elements of this competency.

Figure 12-2 Apply quality improvement: Key elements.

A diagram illustrates the key elements of applying quality improvement.

The Core competency, Apply Q I is in the center. Surrounding it are six key elements: safety in health care, quality health care, patient role in Q I, critical tools to improve care, Q I, quality in nursing delivery systems, and patient role in Q I.

Data indicate that there are serious problems with health care in the United States-its safety, quality, and waste and inefficiency. It is a problem that the U.S. Congress has addressed, indicating its importance to the public. In 2014, the U.S. Congressional Subcommittee on Primary Health and Aging held a meeting to examine healthcare errors: “Preventable medical errors in hospitals are the third leading cause of death in the United States, a Senate panel was told today. Only heart disease and cancer kill more Americans . . . Medical harm is a major cause of suffering, disability, and death-as well as a huge financial cost to our nation,” Senator Bernie Sanders commented. The press release went on to state, “[E]ach year as many as 440,000 people die due to a preventable medical error in hospitals. Compared with other nations, the United States is about average. In addition to deaths and injuries, medical errors also cost billions of dollars. One study conducted in 2011 put the figure at $17 billion a year. Counting indirect costs like lost productivity due to missed workdays, medical errors may cost nearly $1 trillion each year . . .” (U.S. Congress, Subcommittee on Primary Health and Aging, 2014). Experts commented on healthcare quality by noting recent studies supporting these comments-"if we identified errors as a disease then when tracking death rates per disease, errors would be the third leading cause of death in the United States” (Makary, 2016). This is a strong statement, and it had an impact on increasing efforts to improve and recognizing that the federal government is engaged in assessing, describing the problem, and collaborating to improve. The picture is not all bleak as there has been improvement since the report, To Err Is Human, but there has not been enough. The examples provided in this chapter content and in Exhibit 12-1 indicate major problems still exist more than 20 years after the publication of To Err Is Human (IOM, 1999).

| Exhibit 12-1 Examples of Quality Care Issues |

|---|

| The following represent several examples of problems that have occurred in the last few years in HCOs that have had a serious impact on patients and their health outcomes. Some have been resolved, and some are ongoing. |

| National Institutes of Health Clinical Center |

| The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center has long been thought of as an exemplary healthcare setting that offers care for unique medical problems and clinical trials for research studies; however, in 2016, there was significant criticism of the clinical center and its care. Leadership at the center disputed the claims of poor quality (NIH, 2022; Kaiser, 2016). The report identified several recommendations for improvement: (1) Fortify a culture and practice of safety and quality; (2) strengthen leadership for clinical quality, oversight, and compliance; and (3) address sterile processing of all injectables and the specifics of the sentinel event that set this review in operation (NIH, ACD, 2016). Since this time, steps have been taken to improve. |

| Veterans Health Administration |

| In 2014, there was extensive reporting of abuse in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) that focused on putting patients on appointment wait lists for long periods of time, and some were never seen for care. This is poor care, but documentation changes were added to make it look as if there was no problem. The inspector general for the VHA investigated this fraud and unethical actions. In 2016, problems continued in some VHA medical centers-for example, with the inspector general continuing to investigate care and misconduct incidents (Krause, 2016). Examples of other problems were environmental concerns in the operating rooms and fraud and cover-ups that included nurses' involvement (Rebelo & Santora, 2016). |

| A Nurse as a Whistleblower |

| A nurse in an academic health center sued the health center for covering up infections and then limiting the use of standard checking of equipment used in procedures to ensure sterility (Becker's Hospital Review, 2016). If the equipment is not checked, data collected will not identify problems, and performance then appears to be better than it might be. The nurse asked that the procedure for checking equipment routinely be maintained and requested an external audit. The requests were rejected. The nurse sued under the whistleblower law, as discussed in other text content on legal and ethical issues. Employers cannot retaliate for this type of employee action. |

| Lost Newborn Body |

| An academic medical center lost the body of a newborn after death during delivery. This is an unusual situation and is a sentinel event. There are procedures and policies that should be applied when a death occurs in an HCO, including care of the body. This did not happen in this case when a woman delivered twins; one was stillborn, and the second lived an hour (CBS News, 2015; Fieldstadt, 2015). |

| Whistleblower: Visiting Nurse Service Fraud |

| At one of the largest nonprofit home healthcare agencies in the United States, a senior manager filed a whistleblower lawsuit for fraud that resulted in hundreds of millions of dollars taken from Medicare and Medicaid. This fraud included falsified and improper billings. This resulted in many patients receiving a fifth or less of prescribed care. Patients were not told about changes in their service level nor were physicians notified. An example of fraud in this case was a nurse who claimed to have made 20 home visits for nine patients in one day, something that could not have occurred. Other nurses made similar claims of visits that they could not have been made in the timeframe identified. Exhibit 12-2 provides other examples with links to additional information. |

| Exhibit 12-2 Examples of Poor Quality and Safety |

|---|

|

When considering quality and ethics, such as the examples about better staffing, “[m]uch of the public discourse around the hospitals' purportedly unethical behaviors misses an important nuance-namely, that hospitals' staffing decisions are shaped by a complex system of economic and regulatory constraints created and overseen by governmental payment policies and largely replicated by private payers. Improving hospitals' behavior will require changing the policies that currently allow-and even inadvertently incentivize-hospitals to increase their operating margins through inadequate staffing” (Yakusheva & Rambur, 2023). Staffing, budget, and policies have a direct impact on quality and safety in health care. This can be a conflict for HCOs and healthcare providers, as funding, for example, reimbursement, is necessary, and funds must also be used for other expenses, but staffing is critical and costly. Policies and even politics are involved in this complex concern. Nurses are speaking out about their concerns, for example, engaging in a march to push for safer staffing in Washington, D.C. (Minnie, 2022).

| Stop and Consider 1 |

|---|

| Every nurse is expected to meet the QI competency. |

Quality Health Care

In 1970, the Institute for Medicine (IOM) was founded as a private, nonprofit, nongovernmental institution that works to provide objective expert advice and is now known as the National Academy of Medicine (NAM). Its mission is to “advance science, accelerate health equity, and provide independent, authoritative, and trusted advice nationally and globally” (NAM, 2023). Since the late 1990s, there has been an increase in efforts to examine healthcare quality. The NAM is a leader in this effort, consulting with experts, collecting and analyzing data, and publishing reports with recommendations on a variety of topics related to healthcare quality. This series of reports is often referred to as the Quality Chasm reports. The following describes the major initial reports in this series. These are important sources of information for healthcare policy, providers, professional organizations, and healthcare profession education.

To Err Is Human

The first report in the Quality Chasm series was To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System (IOM, 1999). This report explored the status of safety in the U.S. healthcare delivery system. The results were dramatic, with data indicating serious safety problems in hospitals. This examination did not include other types of healthcare settings, such as ambulatory care, home health care, long-term care, and other types of sites. More research was needed to provide data about the quality of care and safety in these settings. An example of the influence of this research is the report published by the Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ): AHRQ Health Information Technology, Ambulatory Safety and Quality: Findings and Lessons from the AHRQ Ambulatory Safety and Quality Program. The report described studies about ambulatory care, but the report noted more information was needed to support strong conclusions (HHS, AHRQ, 2022). As discussed in this chapter, an effective understanding of quality requires clear data that are useful for monitoring and measuring healthcare outcomes.

Some of the data from the initial Quality Chasm report that disturbed the public and healthcare providers included the following and set the stage for major initiatives to improve care (IOM, 1999, pp. 1-2):

- When data from one study were extrapolated for the 1999 IOM report, the result suggested that at least 44,000 Americans die each year due to medication errors. To compare the 1999 report data, more recent studies indicate the number of deaths from this cause could be as high as 98,000 (AHA, 2023).

- More people die in a given year as a result of medical errors than from motor vehicle accidents (43,458), breast cancer (42,297), or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (16,516) (HHS, CDC, NCHS, 1998). Deaths from medical errors continue to be a problem, but research on this issue is complex and requires careful consideration of the methods used.

- Healthcare delivery costs represent more than half of total national healthcare costs, which include lost income, lost household production, disability, and actual healthcare delivery costs (Thomas et al., 1999). Healthcare costs continue to increase.

These examples are no longer current, but they are important in understanding the significance of this report when it was published. Later in this chapter, HCO accreditation is discussed in detail; however, it is important to note that accreditation, focusing on evaluating the quality of care in HCOs, has long been the major method for supporting quality health care. It is clear from To Err Is Human that accreditation was not enough to improve care at the level needed, and as noted in this chapter and text, more needs to be done.

The media took note of To Err Is Human and its recommendations, and soon worrisome stories appeared on the evening news and in newspapers; special in-depth news reports asked, “How safe are you when you receive health care?” Consumers began to ask questions. Healthcare errors experienced by patients and errors reported in the media reduce the public's trust in the healthcare system. The result is that patients and families question their care more. Some patients now want a family member or friend with them when they are in the hospital, not just for support but also to act as a protector from errors. When a patient experiences an error, the patient's trust level drops, and this has an impact on how the patient approaches future care. There is a positive side to this situation. More patients are now demanding that they be informed about their care, and therefore, they are becoming more involved in the care process. Patient/person-centered care (PCC) has developed with this increase in patient concern about quality care. (See Saad reference in Exhibit 12-2for additional information about current consumer views of healthcare.)

When strategies are used to prevent errors and improve care, it is important to recognize there is not a specific single answer to this problem. Changing the status of quality care requires multiple planned strategies in practice and management and an increase in QI education in professional healthcare programs, such as nursing education and staff training.

Crossing the Quality Chasm

Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001a) is the report that followed To Err Is Human (IOM, 1999) in the Quality Chasm series. This report's major message was influenced by the 1999 report and indicated that the U.S. healthcare system needed fundamental improvement. Although the healthcare delivery system has undergone many changes-such as the development of new drugs, medical technology and innovation, and healthcare informatics that have improved care and care options-more needed to be done. The 2001 report provided valuable information to help nurses better understand quality issues in the healthcare system; however, if this information is not applied to improve care, it serves little purpose. The report identified six aims or goals for improvement that continue to be relevant. Care should have the following characteristics: safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, and patient/person-centered care (STEEEP®) (IOM, 2001a, pp. 5-6). This type of care ensures that patients receive the services they need (effective care), when they need care (timely care), in the most cost-effective manner (effective and efficient care), and that efforts need to be made to prevent problems (safe care) that might occur due to the errors or poor-quality care (quality improvement). As noted in other Quality Chasm reports, healthcare professionals must also recognize diversity and ensure that disparities are limited when care is delivered, and today there is even greater emphasis on supporting health equity or equitable care. The critical element that connects all of this is health care, which is focused on the patient/person with the patient participating in the care process, PCC. Healthcare competencies relate to STEEEP®, and these aims continue to be viewed as critical healthcare delivery elements (IOM, 2003).

The Quality Chasm series is unique in that the reports do not stand alone but rather expand on previous reports in the series. This interconnectedness makes it important for readers to understand the general information in each report, the ways in which the reports relate to one another, and the recommendations and joint implications for nursing and health care. For example, STEEEP® is related to all the reports and is now a central feature in HCO QI programs. It is also included in national QI initiatives to better ensure continuous quality improvement.

To ensure improved healthcare, the system needs to meet the six aims identified in the Crossing the Quality Chasm report. New rules for the 21st century were developed to guide healthcare delivery, describing a vision of health care. The rules focused on various aspects of care as noted here with some comments about their relationship to nursing practice (IOM, 2001a).

- Health needs are not static, and care must change to meet them, providing a continuous experience. Consider these factors and examples: the nurse-patient relationship, continuum of care, collaboration and coordination, HCO services and systems, diversity, interprofessional teams, communication, and nursing standards.

- Patients are individuals requiring care to match their needs: patient/person-centered care. Patient needs and values also constitute one of the sources of evidence for evidence-based practice. Consider these factors and examples: nursing care and planning, interprofessional teams, PCC, collaboration and coordination, diversity and health equity, patient rights, and patient education, all of which relate to nursing standards and the nursing code of ethics.

- Patients need information to make decisions about their own care-this is essential to patient/person-centered care. The healthcare system and professionals need to share information with patients and bring patients into the decision-making process. Consider these factors and examples: plan of care, interprofessional care, and informed consent provide information for the decision maker, privacy and confidentiality, patient education, patient rights and professional ethics, and informatics.

- Patients need access to their medical information, and clinicians also need access-sharing information when needed. This rule relates to all healthcare competencies, particularly to applying informatics. Consider these factors and examples: informatics, interprofessional teams, sharing information in the nursing care process, patient/person-centered care, privacy and confidentiality, patient education, computerized documentation, professional ethics, and standards. As discussed in this text, digital health (telehealth/telemedicine) is an expanding area of health care. The COVID-19 pandemic increased the use of digital health and the need to share information electronically when patients and healthcare providers had limited physical interaction.

- Patients need care that is based on the best possible available evidence. Care should not vary illogically from clinician to clinician or from place to place. Consider these factors and examples: PCC, nursing research and other areas of research, research-informed consent, EBP, and plan of care.

- Patients need to be safe from harm that may occur within the healthcare system. More attention needs to be placed on system errors rather than just individual errors. Consider these factors and examples: PCC, CQI, nursing care provided in a safe manner, inclusion of safety in the plan of care, patient safety and errors, types of errors, staff safety, culture of safety, and reimbursement (for example, Medicare limits reimbursement if a patient experiences a fall in the hospital).

- The healthcare system should make clear and timely information available to patients and their families that allows them to make informed decisions when selecting a health plan, hospital, or clinical provider or when choosing from recommended treatment options. This should include information that describes the system's performance on quality, EBP, and patient satisfaction. Consider these factors and examples: interprofessional teams, informatics, privacy and confidentiality, patient values and preferences, informed consent, research, patient education, report cards, ethics and standards, and national reports on quality and disparity.

- Healthcare providers and the health system should not just react to events that may occur with patients but should anticipate patient needs and provide needed care. Consider these factors and examples: assessment, interprofessional teams, nursing care process, plan of care, collaboration and coordination, HCO services, patient satisfaction, diversity, and outcomes.

- Resources should not be wasted-including patient and staff time. Consider these factors and examples: use of resources for care delivery, costs of care, access to care and services, staff communication, and issues of misuse , overuse , and underuse .

- Collaboration, coordination, and communication are critical factors that determine effective healthcare professionals and systems (interprofessional teamwork). Consider these factors and examples: interprofessional team plan of care requires team collaboration and coordination.

These rules provide a vision of what healthcare delivery should be if we are to ensure quality care for all. They provide nurses with a guide in developing improvement initiatives and strategies. We continuously work to meet these requirements when care is provided to individuals, families, populations, and communities.

Envisioning the National Healthcare Quality Report

Envisioning the National Healthcare Quality Report (IOM, 2001b) is the follow-up report to Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001a). The United States did not have a structured method to monitor and measure healthcare quality, but this report recommended changes to resolve this problem. It described a framework for collecting annual national data about healthcare quality and focused on the U.S. healthcare delivery system's performance in providing personal health care. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) is now mandated to collect data using this framework and then publish an annual report describing the status of U.S. healthcare quality, which is made available on the internet. This has provided the United States with a structured monitoring and measurement method and regular reporting of data and analysis. Elsewhere in this chapter, healthcare report cards are discussed. An annual national report card, such as the AHRQ report, does not replace the need for individual HCOs to monitor their own quality, such as by using an HCO-specific healthcare report card. The information from the national annual report card can be used by HCOs in comparing their QI data with national data and then use this information to further develop effective services. Healthcare professionals (providers), insurers, and health policymakers should review this information routinely to better understand current healthcare quality and consider strategies to improve it. Nurse educators should use this information in planning curriculum and teaching-learning strategies to ensure that students are prepared to practice effectively based on current needs.

Because the quality report and the national disparities report, which was also the responsibility of the AHRQ, were interrelated, in 2010 they were merged into one report, the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report (NHQDR) (HHS, AHRQ, 2011). This report is designed to meet the following needs: use measurement based on best methods; identify issues that improve or act as barriers to quality care; collect data about care quality and disparities; educate the public, healthcare professionals, organizations, and so on about quality care and disparities; assist policymakers in improving care and reducing disparities; identify key benchmarks; compare U.S. health care with other countries; continue to improve measurement so that data are available and useful; examine healthcare issues that might affect quality of care and disparities; and report data and results. The annual report tracks outcomes for the priority areas of care and health equity and adjusts priorities based on annual results.

We now have more than 10 years of data from these monitoring reports, and the reports influence decisions made about health policy and QI. Because it takes time to collect and analyze data, the published reports are typically one to two years behind the current year. The monitoring methods used to collect and analyze the data are reviewed periodically to ensure their usefulness and the quality of the data, resulting in changes in this report process. The current NHQDR can be accessed at the AHRQ's website (HHS, AHRQ, 2023a).

Defining Quality Health Care

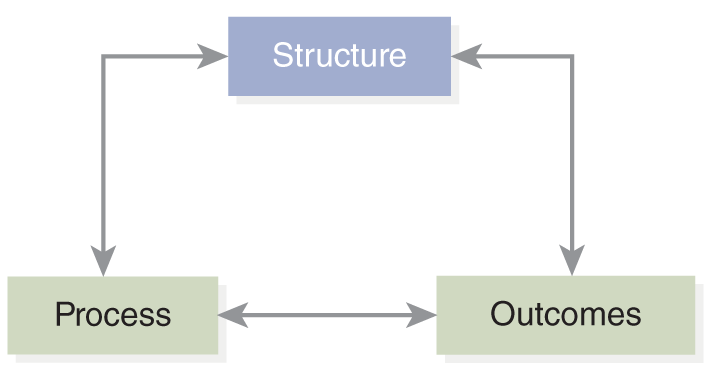

There is no universal definition of healthcare quality, which makes it difficult to assess quality. For this discussion, the following definition and other information provided here will be used in this chapter and applied in other chapters: the “degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (IOM, 1990, p. 4). Quality is a complex concept, and who is defining it can make a difference; for example, a nurse, a physician, and a patient may have different definitions of quality. The following and Figure 12-3 identify the three elements described as having long been included in discussions about quality care and monitoring care (Donabedian, 1980).

Figure 12-3 Three elements of quality.

A diagram depicts the three elements of quality: structure, process, and outcomes, with arrows indicating their interconnections.

- Structure: The environment in which services are provided; inputs into the system, such as patients, staff, and environments.

- Process: The manner in which services are provided; the interactions between clinicians and patients.

- Outcomes: The results of services; evidence about changes in patient's health status in relation to patient and community needs.

A recent study examined the current relevance of the Donabedian model and indicated the model continues to be relevant in QI activities (Pogorzelska-Maziarcz et al., 2023). The study included 3,027 participants with 68% reporting that the number of patients assigned to each staff impacted how the staff were able to apply protocols. This is part of the structure element. Other factors were included in the assessment of the impact of structure, such as inadequate staffing, weakness in staff expertise, and inadequate resources. The process element included processes related to following safety protocols, assessment, and surveillance, PPE equipment and isolation policies, limitations in maintaining isolation, the need to prioritize and cluster care, and identifying and limiting staff who should be in certain areas of care. In examining the third element, outcomes, participants (staff) indicated that they felt inadequate staffing and high patient acuity led to adverse patient and staff outcomes. The study concludes: “These findings highlight the need for health care organizations to support frontline nursing staff in adhering to patient safety and infection prevention and control protocols during times of crises. Infection preventionists have substantial contact with bedside nurses and should leverage their collegial relationships to promote patient safety” (Pogorzelska-Maziarz et al., 2023, p. 1399). The application of this model in HCO QI is very common, and this approach has proven to be helpful.

| Stop and Consider 2 |

|---|

| It is not easy to define quality health care. |

Safety in Health Care

Safety is a critical component of quality care. It is important to recognize the relationship between safety and quality because it is easy to assume that safety is something different from quality care rather than to view it as an integral component of QI. An effective HCO QI program monitors all aspects of quality so that safety for patients and staff is included. There is no question that healthcare providers, including nurses, have long been concerned about providing safe care for their patients. If one interviewed healthcare providers, they would say that they want to keep their patients safe. This belief was somewhat shattered when the U.S. Congress and President Clinton's Advisory Commission on Consumer and Quality in the Healthcare Industry requested that the IOM initiate an examination of healthcare safety and make recommendations based on its findings, resulting in the report To Err Is Human (IOM, 1999). In the following content, we explore the topic of safety in healthcare quality: what it is and what can be done to better ensure safe care for all.

It is also important to recognize that healthcare quality, including safety, is a global concern. “Every year, large numbers of patients are harmed or die because of unsafe health care, creating a high burden of death and disability worldwide, especially in low- and middle-income countries. On average, an estimated one in 10 patients is subject to an adverse event while receiving hospital care in high-income countries. Available evidence suggests that 134 million adverse events due to unsafe care occur in hospitals in low- and middle-income countries, contributing to around 2.6 million deaths every year. According to recent estimates, the social cost of patient harm can be valued at US $1 trillion to 2 trillion a year” (WHO, 2021). WHO's action plan on global health safety focuses on the maximum possible reduction in avoidable harm due to unsafe health care globally and supports a safety culture within healthcare organizations using a systems approach with effective leadership.

Critical Safety Terms

The IOM's work on healthcare quality expanded knowledge about safety and errors, in part by undertaking the identification and definition of key terms. This development of common terminology is an important step in addressing the issue. To effectively collect and analyze data nationally requires a shared terminology. Appendix Aprovides definitions for additional critical terms. The following terms are part of this effort. They have relevance for nurses who should be directly involved in care improvement initiatives in HCOs, at the individual healthcare professional level, and in health policy (IOM, 1999; Chassin & Galvin, 1998).

- Safety: Freedom from accidental injury. Example: The patient leaves the hospital after surgery and a three-day stay with no complications, meeting expected outcomes.

- Error: The failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or the use of the wrong plan to achieve an aim. Errors are directly related to outcomes. There are two general types of errors: error of planning and error of execution. Errors may harm the patient, and some, but not all, errors are preventable. Example: The patient is given the wrong medication.

- Adverse event: An injury resulting from a medical intervention; in other words, an injury that is not a result of the patient's underlying condition. Not all adverse events are caused by errors, and not all are preventable. These events require greater examination and analysis to determine the possible relationship between the error and an adverse event. When an adverse event is the result of an error, it is considered a preventable adverse event. Example: A patient is given the wrong medication and experiences a seizure. If the patient does not have a seizure disorder, this is more likely an adverse event, but much more needs to be known about the cause(s). How did the error that led to the adverse event happen? The following factors increase the risk of medication adverse events in the future: the development of new medications, the discovery of new uses for older medications, inadequate patient education and health literacy, health equity, aging of the U.S. population, more over-the-counter medications, and greater use of medications for disease prevention.

- Misuse: Avoidable complications that prevent patients from receiving the full potential benefit of a service. Example: The patient receives a medication that is not prescribed and conflicts with the patient's allergies; the patient experiences anaphylaxis.

- Overuse: The potential for harm from the provision of a service exceeds the possible benefit. Example: An elderly patient takes several medications prescribed by different healthcare providers who do not know all the patient's medications.

- Underuse: Failure to provide a service that might produce a favorable outcome for the patient. Example: The patient is not able to get specialty service needed for cancer because of distance from the healthcare provider, or the patient's insurer will not cover a medication for arthritis that could make the patient more mobile.

- Near miss: The recognition of an event that might have led to an adverse event. This does not mean an error occurred, but rather, it almost occurred. It is important to understand these errors because they provide valuable information for preventing future actual errors. Example: The surgical team is preparing for surgery to repair a patient's knee. The right knee is prepped, but soon after, the team checks the records and goes through a safety checklist prior to beginning surgery, the call-out and check-back, to ensure that the correct knee is exposed-only to find out that it is the left knee that requires surgery. The team stops and considers changes in the plan for the surgery. If there is no consideration of why this error almost happened, then the team cannot learn from it and, hopefully, prevent future errors. One model for understanding near misses and prevention of future errors is the Eindhoven model (van der Schaaf, 1992), which was adapted by nursing and continues to be used to identify three sources of errors (Henneman & Gawlinski, 2004, p. 196):

Technical failure (system error): Physical items, such as software, equipment, or other materials, are not designed correctly, work incorrectly, or are not available when needed.

Organizational failure (system error): This type of error relates to complex factors that affect how work is carried out in the healthcare setting, such as staff orientation, staff expertise, protocols, policies and procedures, clinical pathways, management priorities, budget, and organizational culture.

Human failure: This failure results from behaviors related to skills, rules, and knowledge. Safety mechanisms should include reliable system defenses and the availability of adequate human recovery. Human intervention, such as interventions provided by nurses, can prevent adverse outcomes even when high-risk incidents develop into error incidents.

- Sentinel event: This type of event causes a serious negative patient outcome (unexpected death, serious physical or psychological injury, or serious risk). Example: A patient commits suicide while in the hospital for treatment of diabetes.

If the examination of healthcare quality had concluded with the To Err Is Human report, the major impact of the report and its recommendations would most likely have been diluted (IOM, 1999). This, however, did not happen. In 2004, due to the recognition that much more needed to be known about healthcare quality, follow-up reports were published. The IOM used the following approach to develop the Quality Chasm report series and continues to use it for other reports. A team of experts is identified, and with IOM/NAM staff support, the team (1) describes the problem using data; (2) after analysis, identifies recommendations to respond to the problem(s); and (3), if needed, identifies monitoring methods and possible interventions or solutions. For example, this approach was used to develop the report Patient Safety: Achieving a New Standard for Care (IOM, 2004a) focusing on the need to establish a national information infrastructure and the need for data standards. These elements help healthcare providers and payers improve monitoring outcomes. Having a common language/terminology to use in discussions about safety and errors is critical in meeting the goal to develop a national information infrastructure to support monitoring of care. It also addresses quality improvement competency, which focuses on informatics. This is another example that illustrates how the reports, data, recommendations, and methods used to monitor change are all interconnected. As discussed later and in other chapters, there are now major initiatives that respond to the concerns noted in the Quality Chasm reports and other reports that followed the initial series.

A Culture of Safety and a Blame-Free Work Environment

The typical HCO approach to errors in health care has been to identify the staff member who is thought to have made the error, supported by requiring staff to complete incident reports that describe errors. This type of approach is often punitive in nature and has not been effective in reducing errors, as noted in the IOM's 1999 report. It has not been effective because most errors are not made by an individual but rather are complex and most likely system errors. When an error occurs, the question should not be, who is at fault? but rather, why did our defenses fail? (Reason, 2000). Communication, collaboration, and coordination; interprofessional teamwork; staffing levels and expertise; staff knowledge; patient acuity level; equipment and training to use equipment; delivery processes; the patient's role; and many other factors affect actions taken or not taken in health care. The healthcare system has focused on the “blame game” and not on designing and using structured methods to find out more about all the factors related to an error. Staff members need to feel comfortable-not fearful-reporting errors. This may require providing staff with structured assertive communication training (Chen et al., 2023). The goal now should be developing a blame-free environment or a culture of safety in which staff can practice and openly discuss potential errors or near misses and actual errors. If staff members worry about implications, such as possible impact on their position or performance evaluation, they may not report an error. This can have serious consequences for patients and prevent the system from improving. This type of fear may also prevent staff from communicating near misses, from which much can be learned about potential errors. In the past, if a nurse made a medication error, the nurse might have been routinely required to take a medication review course and a quiz on medication administration with no consideration of analyzing the causes of the error. The following are examples of questions that are important to consider when a medication error occurs in an HCO that supports a culture of safety, demonstrating the complexity of an error situation:

- What are the key questions we should consider in this situation?

- Was the order or prescription transcribed correctly?

- Was the order the best choice for the patient and the patient's problem?

- Was an error made in what the prescriber (physician, advanced practice nurse) intended to order or what the team agreed would be the best approach?

- Was the correct medication sent by the pharmacy? Correct dose? The correct method of administration? Correct time identified and frequency?

- Did the error involve placing a patient medication in the wrong patient's medication box?

- Was the wrong medication and/or dose prepared for administration? Was the administration method incorrect? Was the time or frequency incorrect?

- Was there an equipment malfunction (for example, intravenous equipment, monitoring equipment)? Was the equipment used incorrectly? Was there a computer error? Did the computer send out an alert if set to do so, and if done, why was it not followed?

- What were the distractions and interruptions when the medication was prepared and administered?

- Was the staff member who prepared the medication for administration the same staff member who gave the medication to the patient? If not, why not?

- Were monitoring guidelines followed (for example, vital signs checked)? If data indicated certain actions should be taken, were they taken? If not, why not?

- Was the patient's identification reviewed correctly?

- Was the mediation administration documented as described in the expected procedure?

To accomplish the goal of moving to a culture of safety, there must be (1) a greater understanding of its essential elements, (2) a decrease in barriers to creating the culture, (3) the development and implementation of strategies to create the safety culture, and (4) evaluation of outcomes (IOM, 2004b). Hospitals and other HCOs are moving toward cultures of safety, but it takes time and effort to change staff and administration attitudes and behaviors. It is particularly important to have effective HCO leadership that guides and supports the development of a culture of safety (Anderson, 2006). Trust is important in this type of culture-staff must trust management and vice versa. A topic that comes up often from all types of healthcare professionals is concern about revealing errors and near misses. This is based on past experiences. Moving away from blame means that staff members must trust that they will not be automatically blamed or punished for errors that are out of their individual control. Another aspect of this issue is related to individual staff expectations; nurses may feel that they should not make mistakes and that the care they provide should be perfect. Errors, however, will inevitably occur and are caused by many factors. Improvement is, of course, critical, but to think that errors will never occur is unrealistic. There is no doubt that the number of errors needs to decrease, and what has been done to address errors has not yet been fully effective. Disclosure of errors with maximum transparency must also be used. Ensuring transparency and involving patients are the most difficult aspects of ensuring a culture of safety (Anderson, 2006). “A fundamental principle of the systems approach to error reduction is the recognition that all humans make mistakes and that errors are to be expected, even in the best organizations” (Reason, 2000, p. 768).

It is important to note that a no-blame culture of patient safety does not mean a lack of individual accountability (Wachter & Pronovost, 2009). Though there is now greater emphasis on the recognition of the impact of the system on errors, nurses and other healthcare providers are still accountable for their own practice. When an individual staff member fails to adhere to a safety standard that one is expected to know and apply, and there are no system issues for this failure, then an individual staff member may be accountable for the error. Reporting is an important component of professional accountability. This means healthcare professionals recognize the importance of QI and are committed to active participation in the QI process. Despite these reports, data, and initiatives to improve care and respond to errors-for example, with checklists to ensure that the correct side or body part is operated on in surgery-major problems persist. The Joint Commission reports that wrong site, wrong procedure, and wrong patient (WSPEs) continue to be major problems, representing the most frequently reported sentinel event, and these problems are now the focus of its Universal Protocol to prevent these problems (The Joint Commission, 2023a). QI requires active engagement from all stakeholders to ensure that this type of intervention is used effectively (HHS, AHRQ, PSNet, 2019f).

The HHS, through the AHRQ, is also very involved in supporting safety; for example, it “established the National Action Alliance to Advance Patient Safety as a public-private collaboration to improve both patient and workforce safety. The National Action Alliance is a partnership between HHS and its Federal agencies and private stakeholders, including healthcare systems, clinicians, allied health professionals, patients, families, caregivers, professional societies, patient and workforce safety advocates, the digital healthcare sector, health services researchers, employers, and payors interested in recommitting our Nation to advancing patient and workforce safety to move toward zero harm in healthcare. The HHS recognizes that now is the right time to recommit to advancing patient safety. Progress in safety has been challenged in recent years, by a variety of factors, most notably the COVID-19 pandemic that revealed weaknesses and inequities in the healthcare delivery system. As health systems emerge from the pandemic, their efforts to recover and improve patient care will face competing priorities, including improving equity, addressing staffing shortages, caring for people with Long COVID, harnessing the potential of telehealth and data sciences, responding to climate change, expanding access to behavioral healthcare, and supporting workers' well-being. Addressing these challenges rests on a foundation of patient and workforce safety that requires system solutions” (HHS, AHRQ, 2023b). This action alliance is based on four foundational areas of (1) culture, leadership, and governance; (2) patient and family engagement; (3) workforce safety; and (4) creation of learning health systems, which is described later in this chapter.

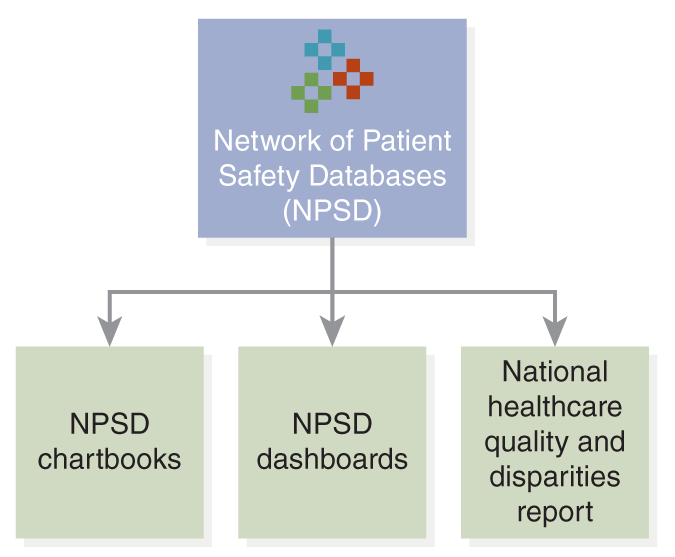

The AHRQ as an active part of HHS also provides resources for healthcare providers and organizations to support patient safety. The Network of Patient Safety Databases (NPSD), as described in Figure 12-4 . This was established by the Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005, and the focus is on evidence-based management resources. The NPSD is also associated with the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report.

Figure 12-4 Network of Patient Safety Databases.

A block diagram of the Network of Patient Safety Databases.

The main block labeled Network of Patient Safety Databases, N P S D, branches out into three blocks: N P S D chartbooks, N P S D dashboards, and National healthcare quality and disparities report.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2023). https://www.ahrq.gov/npsd/what-is-npsd/index.html

Root cause analyses of WSPEs consistently reveal communication issues as a prominent underlying factor. The concept of the surgical timeout-a planned pause before beginning the procedure to review important aspects of the procedure with all involved personnel-was developed to improve communication in the operating room and prevent WSPEs. The Universal Protocol also specifies the use of a timeout prior to all procedures. Although initially designed for operating room procedures, time-outs are now required before any invasive procedure. Comprehensive efforts to improve surgical safety have incorporated timeout principles into surgical safety checklists; while these checklists have been proven to improve surgical and postoperative safety, the low baseline incidence of WSPEs makes it difficult to establish that a single intervention can reduce or eliminate WSPEs (HHS, AHRQ, Patient Safety Network [PSNet], 2019a).

Some of these errors in surgery are difficult to prevent, and some may occur before the patient reaches surgery. For example, consider what happened before surgery to a patient who was scheduled to have cardiac bypass surgery. When the nurse asked the patient to sign the consent form, it listed a different procedure. The patient, who was a physician, pointed out the error and refused to sign. Half an hour later, another nurse brought the patient another consent form to sign, but it was also incorrect. The third consent form was correct and then signed by the patient. This should never happen. What if the patient had not noticed or did not have the background to understand that the surgical procedure described was not what was agreed on between the physician and the patient? This experience also took staff time and increased stress for the patient and family just prior to surgery. Patient trust in staff was significantly reduced at a critical time of stress. This same patient experienced several critical near misses post-surgery with intravenous medications that could have led to cardiac arrest if the patient had not noticed the errors and told the nurse to stop giving the medication immediately, an error that was repeated the next day. When the patient left the hospital, he said, “What has happened to nurses? I have worked with them for years, but their practice has gone downhill. I could have been killed in there.” This highlights the need to improve care, and changing the culture is much more complicated than thought.

It is important to recognize that some HCOs continue to have blame cultures, and more attention should be given to the personal reaction of staff involved in errors, particularly errors that lead to the risk of patient death. How much debriefing occurs after an error, are staff blamed, and in what way? For example, in 2011, a neonatal nurse with 24 years' experience was involved in a medication error that led to the death of an eight-month-old baby; although at the time, it was not clear the error was the actual cause of the death. Immediately after the incident, the nurse was escorted from the hospital, put on administrative leave, and then fired several weeks later. Seven months later, the nurse committed suicide. For more than 3 years, the hospital in which this event occurred described itself as using the “just culture” approach, but this example does not demonstrate this type of culture (Aleccia, 2011). The HHS provides information on support staff who are second victims when errors occur (HHS, AHRQ, PSnet, 2019b). Does this incident send a message to staff not to mention errors? How effective was the organization's just culture-was it just something described in documents but not really practiced? How can employers help staff so that the staff does not become secondary victims if they cannot cope well after an error? Staff emotional distress after an event is not uncommon. In a survey of 3,000 physicians in the United States and Canada, 92% reported experiencing an adverse event, and of those physicians, 81% reported some job-related stress associated with the adverse event that can lead to burnout and low professionalism (Panagiote et al., 2018). Recovery requires time, but it is critical that HCOs maintain an environment of support and offer the provider assistance. Getting support from peers is also important, such as other staff offering to help so that the staff member can have a break from work responsibilities immediately after an adverse event and time to talk about the event in an environment that is not threatening.

The establishment and maintenance of an effective culture of safety requires leadership. This is so critical that The Joint Commission published a sentinel event alert entitled: The Essential Role of Leadership in Developing a Safety Culture (2021). This alert recognizes that when leaders in HCOs do not create an effective culture of safety, this may result in adverse events. The sentinel alert notes that leadership is needed for effective support of event reporting and provide feedback to staff and others who are reporting safety concerns, promote an environment in which staff who report events are not intimidated, use the reporting data to improve, and alert management to staff burnout. This type of leader supports a just culture with appropriate actions to ensure a reporting and learning culture at all levels of the organization. Reducing adverse events can be more effective by using a structured approach, such as the Global Trigger Tool (developed by the Institute for Health Improvement), which is used to assess the overall harm in an HCO. It focuses on monitoring three measures (Griffin & Resar, 2009; AHA, 2023):

- Adverse events per 1,000 patient days

- Adverse events per 100 admissions

- Percent of admissions with an adverse event

Students also have a need for support if an error occurs. It is important that students who are involved in a near miss or an error discuss the experience openly with faculty and ask for support. However, faculty should proactively provide support to students when these situations occur or get qualified persons to assist the student. If this is not done, it reinforces a blame culture-schools of nursing need to also establish cultures of safety or just cultures (Penn, 2014). As we move toward a system view of errors, factors described in Figure 12-5 support a culture of safety.

Figure 12-5 System-level factors that affect safety.

A concentric circle diagram illustrates patient safety factors.

The outermost circle is labeled Institutional, followed by hospital, departmental factors, work environment, team factors, individual provider, and task factors. At the center of the diagram is a line pointing to patient characteristics.

Understand the Science of Safety. Content last reviewed July 2018. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). https://www.ahrq.gov/hai/cusp/modules/understand/science-safety-notes.html

Staff Safety

To Err Is Human focused on patient safety, not staff safety, but the report also states: “Creating a safe environment for patients will go a long way in addressing issues of worker safety as well” (IOM, 1999, p. 20). The lack of information about staff safety in this report does not mean staff safety is not important-it is very important. Another report, Keeping Patients Safe: Transforming the Work Environment of Nurses (IOM, 2004b), included content related to staff safety, particularly related to nurses. Nursing staff members are not immune to workplace injuries. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) is the federal agency that is responsible for monitoring safe workplaces and provides guidance and resources to ensure workplace safety, including healthcare work settings. The American Nurses Association (ANA) is a strong advocate of safety for nurses in all types of healthcare settings. Its position statements on staff safety provide guidelines for healthy work environments. Examples of some of the position statements are available on the ANA website, such as Personnel Policies and HIV in the Workplace, HIV Infection and Nursing Students, HIV Testing, workplace violence and incivility, bullying, and others. Some of the key safety issues for nursing staff other than those mentioned are highlighted here. These statements can be accessed at the ANA website (2023a).

- Needlesticks: Since the 1990s, there has been a reduction in these events due to the application of strategies to reduce them, but they are still a problem. The greatest decreases have been in injuries associated with disposable syringes and winged-steel needles (butterflies) due to advances in safer technologies. However, injuries from sutures and scalpel blades, especially among physicians, continue to be high. Injuries from disposable syringes continue to affect nurses more than any other single professional group (53%). In addition, year after year, approximately 25% of all injuries occur downstream to the nonuser (e.g., waste management staff, laundry worker, etc.). It is important to remember that the use and activation of safety mechanisms and proper disposal protect not just the user of the device but those who encounter the device throughout its lifespan or the procedure (HHS, CDC, NORA, 2019).

- These exposures can lead to hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus that causes AIDS. At least 1,000 healthcare workers are estimated to contract serious infections annually from needlestick and sharps injuries. More than 80% of needlestick injuries can be prevented with the use of safer needle devices, but HCOs must provide them-and nurses need to demand that they are available and use them.

- Infections: As noted, healthcare workers are often exposed to communicable diseases via needlesticks. Other examples of infections staff may be exposed to include tuberculosis, Staphylococcus, cytomegalovirus, influenza, and bacteria. Influenza spread has been linked to suboptimal vaccination levels of healthcare workers; for example, in “2019-2020 flu vaccination coverage among healthcare personnel (HCP) was 80.6%, similar to coverage during the past five seasons (77.3% -81.1%)” (HHS, CDC, 2020). The CDC recommends that healthcare workers in hospitals and long-term care receive the vaccine annually. Some states require this immunization for state employees in healthcare and/or require reports to the state on levels of staff immunization. In states with requirements, employees may submit exemptions, and if they do not get the vaccine, they may be required to wear masks while at work. COVID-19 has clearly reminded the healthcare delivery system and healthcare professionals of the risk of infectious diseases, and this, too, has led to immunization concerns and further issues related to staff requirements. It is hoped that all healthcare providers receive new vaccines and subsequent updates for infectious diseases to protect themselves, their families, other staff, and patients. Another recent infectious disease is the Ebola virus that spread from Africa and the Zika virus, transmitted by mosquitos but not contagious in the work environment unless the nurse is working in an area where the infected mosquitos exist. These situations are examples of the global impact of infectious diseases today; people travel globally, and healthcare providers travel to assist other countries in providing health care for emergencies and on a routine basis. As seen with COVID-19, infectious diseases can directly impact travel, how it is done, when, changes in procedures, and who may travel and have a global economic travel impact.

- Ergonomic safety: Nurses experience a significant number of work-related back injuries and other musculoskeletal disorders. Because of these injuries, some nurses may request transfers to other units or other healthcare settings with less risk, and sometimes they may leave nursing. Typical injuries are to the neck, shoulder, and back. Nursing practice requires a lot of patient handling, and factors, such as the patient's weight, height, body shape, age, dependency, and medical status are important ergonomic issues. There has been an increase in weight in the U.S. adult population in general, and this has increased the risk of injury. The physical workspace is also a factor in increasing risk. There should be enough space to provide care and allow staff to safely move the patient. Nurses should consider the types of available equipment to assist in moving patients, request assistance when needed, and discuss their work needs with management, noting the importance of these factors in ensuring quality care and staff and patient safety. The ANA's “Handle with Care” campaign addresses work-related musculoskeletal disorders (ANA, 2023b). Its goal is to develop and implement a proactive, multifaceted plan to promote the issue of safe patient handling and the prevention of musculoskeletal disorders among nurses in the United States. Through a variety of activities, the campaign seeks to advocate, educate, and facilitate change from traditional practices of manual patient handling to emerging technology-oriented methods. Staff education needs to include content and experiences to facilitate the safe use of the most effective handling methods. In addition, education should put more emphasis on assistive patient handling equipment and devices ensuring that students know how to safely use this equipment. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH, 2023a) also supports guidelines for safe patient handling and mobility.

- Violence: Violence may not be a typical staff safety concern that a student would first think of when asked about safety in the healthcare workplace, but it may be a problem. There is a greater risk of violence in emergency departments, psychiatric/mental health/substance use disorder treatment services, and long-term care facilities; however, such incidents may occur anywhere. Patients and families may not be able to control their emotions appropriately and then respond with anger and violence. The nurse may also be in a situation in which there is violence that is not directly related to the nurse or health care, such as providing home health care in a neighborhood that has a high level of crime and violence. Staff members need training so that they can be alert and prevent violence when possible-particularly training in identifying signs of escalation and use of methods to deescalate a situation when possible. They need to know how to protect themselves when violence cannot be prevented. In areas such as psychiatry/mental health, this training is more common. Signs of escalation include a sudden change in behavior, clenched jaws or fists, threats, pacing, increased movement, shouting, use of profanity, increased respirations, and staring or pointing. These signs do not mean that the person will become violent but rather that the nurse should be more aware of the person's behavior and communication to determine if the person is escalating. Protecting oneself is very important; for example, the nurse may decide it is safer to leave the room, stay near the door, or keep the door open but not appear to be blocking the door; ask other staff to be present; or call for security assistance. It is also important when any weapon is found in patient belongings to secure the weapon and call for professional assistance, such as the HCO's security and the police. HCOs should have a policy and procedure describing the expected staff response in this type of situation. This information should also include requirements for police entering HCOs and carrying weapons (for example, when entering a mental health unit, they must remove their guns).

- Chemical exposure: OSHA offers information on preventing workplace injuries caused by exposure to chemicals, which is something nurses may encounter during their work. Nurses are exposed frequently to sterilizing chemicals, housekeeping cleaners, drug preparation residue, radiation, and other hazardous substances reported to increase rates of asthma, miscarriage, certain cancers, and birth defects (in particular, musculoskeletal defects). There are limited workplace safety standards for the hundreds of hazardous substances to which nurses are exposed on the job (ANA, 2023c; HHS, CDC, NIOSH, 2023b). Other reviews of healthcare workplace safety note concerns about anesthetic gases; hand and skin disinfection; latex (for example, gloves); medications, such as antiretroviral medications and chemotherapeutic agents; mercury-containing devices; personal care products; and sterilization and disinfectant agents, such as ethylene oxide and glutaraldehyde. The ANA continues to monitor risks for nurses and provide information on its website. Nurses need to be aware of past and current data that indicate specific potential problems to protect themselves and their colleagues from exposure and prevent injuries and health problems. In addition, nurses need to be alert to symptoms of allergies to drugs and products that can directly affect their health and practice.

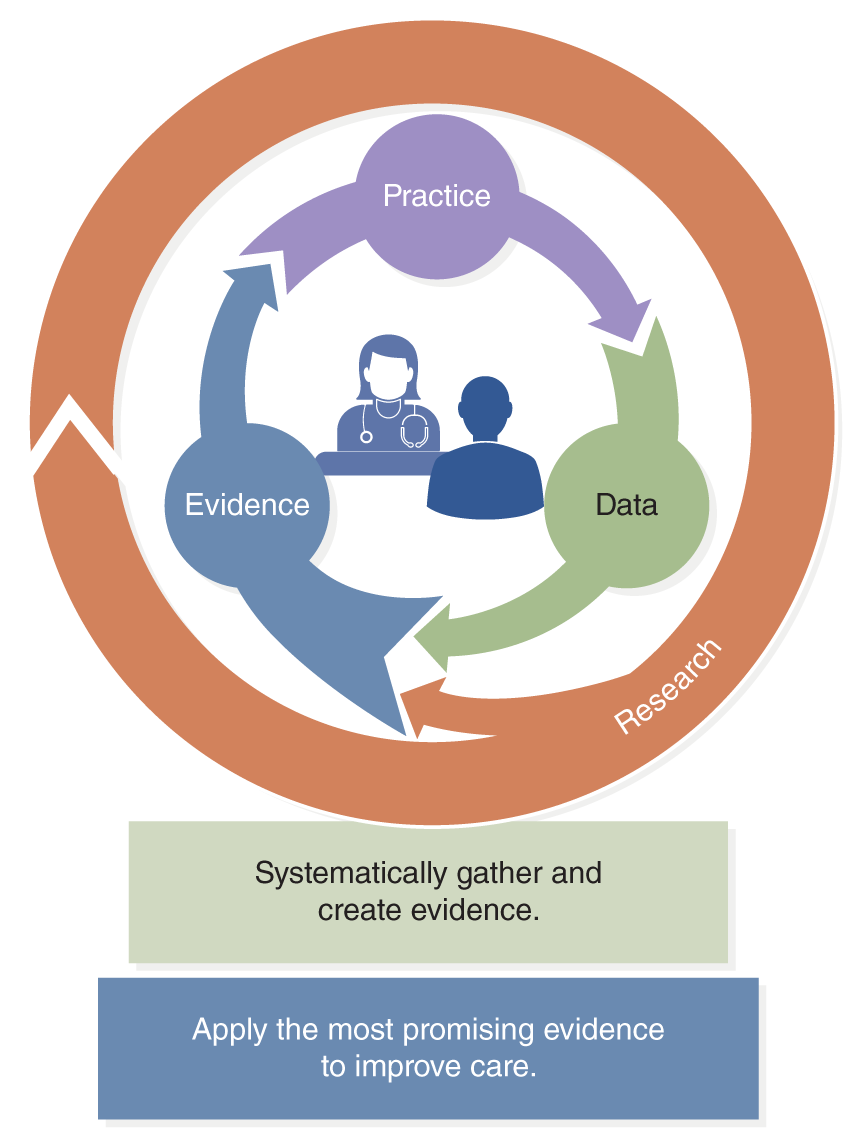

The AHRQ defines a learning health system as “a health system in which internal data and experience are systematically integrated with external evidence, and that knowledge is put into practice. As a result, patients receive higher quality, safer, more efficient care, and HCOs become better places to work. Learning Health Systems include the following, and Figure 12-6 identifies the key elements (HHS, AHRQ, 2019):

Figure 12-6 Learning Health System.

A circular diagram consists of interconnected sections labeled Practice, Data, and Evidence, forming a continuous cycle with arrows.

Inside the circle, there is an illustration of a healthcare provider and a patient. The outer ring is labeled Research. Below the diagram, there are two statements: Systematically gather and create evidence and Apply the most promising evidence to enhance care.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2019). Learning health systems. https://www.ahrq.gov/learning-health-systems/about.html

- Have leaders who are committed to a culture of continuous learning and improvement.

- Systematically gather and apply evidence in real time to guide care.

- Employ informatic technology methods to share new evidence with clinicians to improve decision-making.

- Promote the inclusion of patients as vital members of the learning team.

- Capture and analyze data and care experiences to improve care.

- Continually assess outcomes to refine processes and training to create a feedback cycle for learning and improvement.

| Stop and Consider 3 |

|---|

| Safety is a component of quality health care. |

Quality Improvement

Healthcare quality improvement focuses on the healthcare system, which is fragmented and in need of improvement. Plsek (2001) defined a system as “the coming together of parts, interconnections, and purpose. While systems can be broken down into parts, which are interesting in and of themselves, the real power lies in the way the parts come together and are interconnected to fulfill some purpose. The healthcare system in the United States consists of various parts (e.g., clinics, hospitals, pharmacies, laboratories) that are interconnected (via flows of patients and information) to fulfill a purpose (e.g., maintaining and improving health)” (p. 309). This does not mean that meeting individual patient needs and individual patient care improvement are not important. Each patient's care is part of the overall emphasis on healthcare improvement and is integrated into the system. Ultimately, the goal is that each patient's outcomes will be met, and this has an overall impact on population and community health.

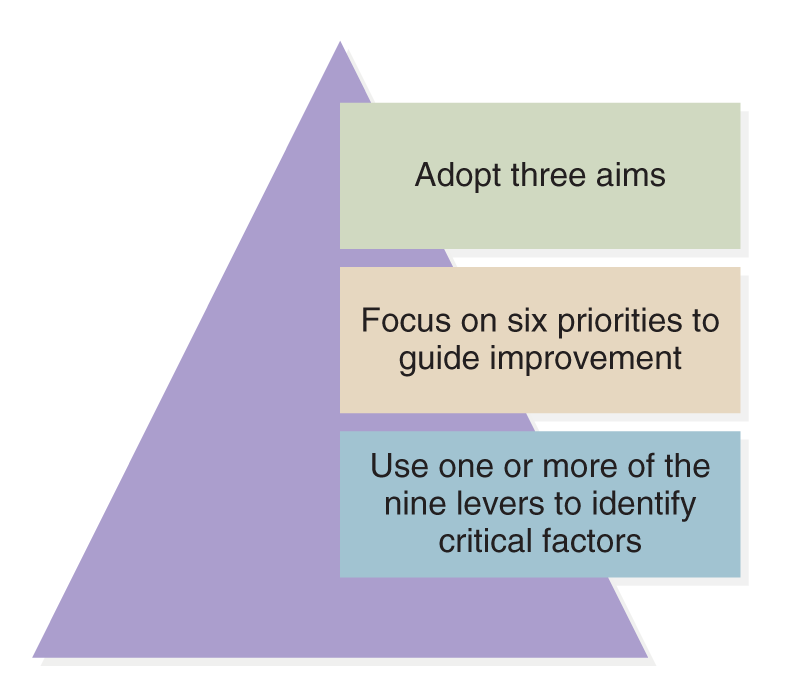

The Institute for Health Improvement suggests that new designs can and must be developed to simultaneously accomplish three critical objectives-that is, the Triple Aim, which is now integrated into most QI efforts, both by HCOs and in health policy, to improve care on a continuous basis. The aims are (IHI, 2023a):

- Improve the health of the population.

- Enhance the patient experience of care (including quality, access, and reliability).

- Reduce, or at least control, the per capita cost of care.

More recently a fourth aim has been added: To improve the work life of healthcare providers. This addition recognizes the importance of staff safety (Feeley, 2017).

You will observe and be involved in issues of quality care as a student and then as a nurse in practice. Entering the healthcare system and the nursing profession, you may have doubts that QI is an important topic, particularly if you have found the health system to be effective for you and your family. In this case, this might demonstrate that the healthcare system or HCO in which you received care had an effective QI program that you might not know about. There are, however, serious problems that have been reported routinely in major reports, by the government, organizations, healthcare providers, and consumers. The content in this chapter is critical for you as a nurse as you engage in efforts to improve care daily for your individual patients, families, communities, and the healthcare system.

QI needs to be viewed as a continuous process as there is no end point, so it is often referred to as continuous quality improvement. When QI is discussed, there are several perspectives to consider. The first and most critical is your individual practice. What you do as a nurse has a direct impact on patient outcomes and quality. This chapter and other content in this text guide you in understanding your responsibilities and the importance of your engagement in CQI. There are two other perspectives that affect individual healthcare professionals and healthcare quality in general. One of the perspectives is the structure and processes of HCO QI programs that are designed to support the HCO efforts to maintain and improve care quality. The second view is the health policy perspective-QI initiatives from the local, state, and national levels and related requirements that influence how HCOs maintain and monitor CQI. These perspectives should be in sync to ensure effective health care for patients, families, and communities.

Implementing QI “requires that health professionals be clear about what they are trying to accomplish, what changes they can make that will result in an improvement, and how they will know that the improvement occurred” (IOM, 2003, p. 59). Healthcare complexity is mentioned many times as a barrier to understanding quality and improving healthcare delivery. Its consumers are very diverse in their needs, diagnoses, ethnic and cultural backgrounds, and overall health status, including genetic background, socioeconomic factors, patient preferences for health care, community differences, and healthcare coverage/reimbursement. Health care cannot be viewed in the same manner as other businesses (such as the automobile industry) that might manufacture or sell one product or a series of highly related products. Healthcare products/services vary based on the medical problem and the patient, the setting, the expertise of clinical staff, diagnosis, treatment options, patient decisions, patient prognosis, health policy and legislation, advances in science, medical technology, and health informatics technology (HIT). Even in specialty areas, such as obstetrics, psychiatry/mental health, emergency care, intensive care, home health care, and long-term care, there is great variation within the services-in their interventions, patient and family roles, patient education needs, prognosis and outcomes, and so on. It is expensive to develop and maintain effective QI programs, but The Joint Commission requires such programs for all its accredited organizations to guide HCOs and their staff in improving care daily and reimbursement sources, such as for Medicare and Medicaid and other insurers, also expect ongoing QI activities (Finkelman, 2022).

Because of the complex nature of quality, developing an HCO QI program that addresses monitoring and improving healthcare quality is in and of itself a complex process. HCOs typically have a department with staff that focus on CQI. This requires staff and a budget for these efforts, and the program must plan, implement its plans, monitor and measure quality, and then identify and implement interventions and solutions to maintain quality or improve quality. Effective appraisal of the scientific facts suggests that health care can be improved by closing the wide gaps between prevailing practices and the best-known approaches to care and by developing new forms of care-applying evidence-based practice (EBP). This requires planning and careful evaluation of results. One model for improvement focuses on three key questions that continue to be important today, which are (Berwick & Nolan, 1998, p. 209):

- What is the HCO trying to accomplish?

- How will the HCO know whether a change is an improvement?

- What change can the HCO try that it believes will result in improvement?

Even in the earliest reports on quality care, it was noted that for an HCO to have an effective QI program, nurses and other health professionals need to be knowledgeable and competent in a number of areas, and this view has continued as QI developed (IOM, 2003). All aspects of the healthcare environment are important to consider, such as patients, staff, and their interactions; patient and healthcare outcomes; and changes in science, technology, and the needs of individuals and communities. HCOs need to consider and compare factors with other HCOs and similar healthcare systems to determine the best current practices and then develop and apply interventions to improve care. This all requires an understanding of quality issues-errors, risks, human factors-that affect quality care for patients and staff safety, monitoring, and measurement. Surrounding all of this is the need to integrate interprofessional teamwork in CQI and in care practice.

| Stop and Consider 4 |

|---|

| QI is a continuous process (CQI). |

Examples of Quality Initiatives

The Quality Chasm series of reports stimulated the development of several important safety initiatives. The IHI, for example, was established in 1991 and describes itself: “For more than 25 years, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) has used improvement science to advance and sustain better outcomes in health and health care across the world” (IHI, 2023b). The IHI also focuses on STEEEP®. The 5 Million Lives Campaign is one example of an IHI safety initiative. This voluntary global initiative sought to protect patients from 5 million incidents of medical harm over 2 years (December 2006-December 2008) (IHI, 2023c). This initiative led the IHI to further develop its resources to improve healthcare quality, such as an improvement map designed to help hospitals respond to multiple requirements they face and to focus on high-leverage changes to transform health care. A newer IHI initiative was the 100 Million Healthier Lives Campaign with a projected worldwide goal by 2020 (IHI, 2023d). The COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on this initiative, which was not expected when the campaign was developed, so time will be needed to determine its impact on global health status.

Another initiative, a collaborative effort between the IHI and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), focuses mostly on nursing-Transforming Care at the Bedside (TCAB). TCAB is a “unique innovation initiative that aims to create, test, and implement changes that will dramatically improve care on medical/surgical units, and improve staff satisfaction as well” (IHI, 2023e). This program supports and guides pilot QI projects to improve care developed at the point of care by staff in practice, offering many opportunities for improvement and engaging nurses in the QI process. The framework includes (RWJF, 2020):

- Safe and reliable care

- Vitality and teamwork

- Patient/person-centered care

- Value-added care processes

The Joint Commission's (2023b) annual safety goals, which were first introduced in 2003, is a safety initiative developed by the major healthcare accreditation organization and, thus, has an impact on many HCOs. Each year, The Joint Commission identifies safety goals that should be the focus of every HCO accredited by The Joint Commission. These goals identify critical current safety concerns based on data The Joint Commission collects and analyzes from its accredited HCOs, as well as other sources of information about healthcare safety. An example of awareness of changes in health care is the addition of healthcare disparities, quality and safety, and equity in its standards (The Joint Commission, 2023c). The organization's accreditation surveyors emphasize the annual safety goals during accreditation visits. HCOs typically provide staff education related to the goals and monitor goal progress. Nursing students need to know the current safety goals and integrate them into their clinical learning experiences. The current annual goals are available on The Joint Commission website (2023d).

The Joint Commission Accreditation

Accreditation is the process used to evaluate organizations, particularly focused on quality and based on minimum standards. The major organization that accredits HCOs is The Joint Commission, a nonprofit organization accrediting more than 22,000 HCOs in the United States, including hospitals, home healthcare agencies, clinical laboratories, ambulatory care organizations, behavioral health, and nursing care centers (postacute, subacute, long-term care). It also accredits HCOs in other countries (The Joint Commission, 2023b). This accreditation organization has been in operation since 1951, and over that time, the accreditation requirements and process have changed to adjust to changes in healthcare. Participating in a Joint Commission accreditation survey is time-consuming and costly, but it is necessary for HCOs. For example, nursing education programs need to use HCOs with current Joint Commission accreditation for student practicum/clinical experiences. As The Joint Commission has changed, its emphasis on quality care has also changed. CQI is now the major focus of the accreditation process, which includes safety.

Nurses serve on The Joint Commission Nursing Advisory Council, which advises The Joint Commission about nursing concerns and care issues related to quality and accreditation. Nurses who work in HCOs eventually experience the Joint Commission survey. After initial accreditation is received, The Joint Commission surveyors visit the accredited HCO every 3 years to complete its intensive survey for accreditation renewal, and it may even make unscheduled visits. For the scheduled visits, the HCO is given a date and has 9-12 months to prepare for the visit. Preparing for the visit involves gathering information and data for The Joint Commission, preparing written reports, educating staff about the standards, conducting mock surveys to prepare staff, and so on. The HCO should always meet the expected accreditation standards, not just at the time of a survey. In the past, great emphasis was placed on getting ready for The Joint Commission visit and surviving it; afterward, the HCO was less vigilant until it was time to prepare for the next visit. This approach of just focusing on the survey every 3 years eventually changed, and now accredited HCOs must submit reports on certain data to The Joint Commission annually, with a plan of action for areas noted in the self-assessment that may require improvement (periodic performance appraisal/review); in addition, HCOs must be prepared for possible unscheduled visits or requests for additional data.