The content in this chapter addresses ethical and legal issues in nursing. As a profession, nursing has ethical responsibilities, which in some cases are connected to legal issues and in others are not related to legal concerns. In the practice of nursing, ethical and legal issues often arise, and the nurse must understand them and take appropriate steps to address them. These issues involve professionalism, practice concerns, health policy, reimbursement issues, and the organizations that provide health care.

Ethics and Ethical Principles

All healthcare professionals consider ethics in their practice, whether they recognize it or not. Nurses need to understand ethics and the ethical principles that drive healthcare decisions and the nursing profession and impact their individual practice.

Definitions

The first question that is asked in this type of content is: What is ethics? It is easy to confuse ethics with morals. Morals refer to an individual's code of acceptable behavior, and they shape one's values and are influenced by cultural factors and personal experiences. Ethics refers to a standardized code or guide to behavior. Morals are learned through growth and development, whereas application of ethics typically is learned through a more organized system, such as a standardized ethics code developed by a professional group. Ethics deals with the rightness and wrongness of behavior. Bioethics relates to decisions and behavior related to life-and-death issues. The latter sometimes comes in conflict with a patient's or nurse's personal morals, values, and ethics. There may be conflict between a nurse's and a healthcare organization's (HCO) approach to morals, values, and ethics. Health policy also involves ethical decision-making, particularly when cost-benefit analysis is used.

Ethical Principles

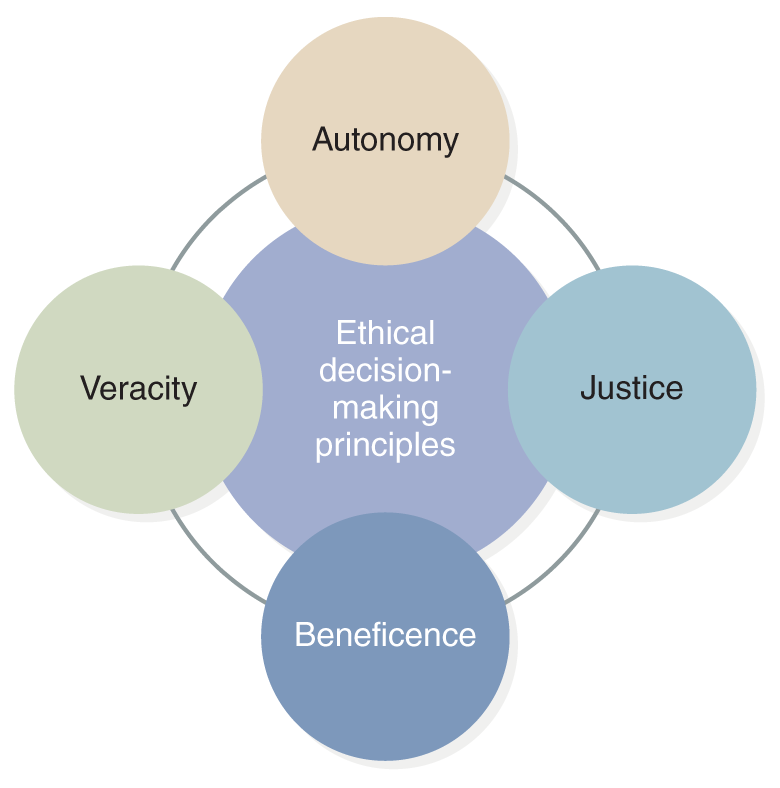

Four ethical principles are used in nursing and healthcare delivery, highlighted in Figure 6-1. Ethics is a difficult area in professional practice, and these principles help guide nurses when confronted with ethical issues. Throughout this chapter, the term “patient” will be used, but in the case of a minor or a person who is under legal guardianship or power of attorney, “patient” also refers to the family or the guardian who makes the decisions in such cases. The four principles are autonomy, beneficence, justice, and veracity:

Figure 6-1 Ethical decision-making principles.

A diagram organizes four central concepts critical to ethical decision-making into interconnected circles. Each circle is labeled with one of the principles: autonomy, justice, veracity, and beneficence.

- Autonomy focuses on the patient's right to make decisions about matters that affect the patient. This means that if the patient wants to be involved in treatment decisions, the patient makes the final decisions about treatment while the healthcare provider makes recommendations. Patients need complete and open information or informed consent. The nurse's role is to provide information to better ensure that others, such as the physician, inform the patient and then support the patient's decision. Supporting the patient's decision is not always easy because, in some situations, the nurse may think that the patient is making the wrong decision. It is not the role of the nurse to argue with the patient but rather to act as the patient's advocate, respecting the patient's choice. The nurse can discuss the decision with the patient and ensure that the patient recognizes the potential consequences of the decision. This principle is directly related to patient/person-centered care (PCC).

- Beneficence relates to doing something good and caring for the patient. This principle encompasses more than just physical care-it involves awareness of the patient's situation and needs. In the case of nurses, this also means doing no harm and safeguarding the patient, or nonmaleficence.

- Justice is about treating people fairly-for example, when deciding which patients receive treatment, it may mean some patients do get treatment or preferred treatment. There are more concerns about justice in health care today because of problems with disparity (for example, some people are not getting care when they need it) and the need for equity, discussed in several chapters in this text. Lack of justice can lead to disparities in health care, and this has an impact on quality care and on the public's health.

- Veracity means truth. For example, what information is the patient given during the informed consent process? Trust plays a major role in this principle. Veracity can be a difficult principle to apply because, sometimes, a family member may request that the patient not be fully informed. Such a request is in direct conflict with ethical practices and PCC. Some believe that if another principle is involved, it might be considered first before veracity comes into play. For example, if it is believed that the truth would cause more harm, does beneficence outweigh veracity? In any ethical dilemma, it is important to remember that no two situations are the same. Trust is also related to informed consent requirements, patient privacy, and confidentiality requirements.

Other principles have been suggested that are applicable in today's healthcare delivery system-for instance, advocacy; caring; PCC, human rights; management of resources; respect; honesty; recognition of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI); and privacy and confidentiality.

Ethical Decision-making

Ethical decision-making is associated with ethical dilemmas, which occur when a person is forced to choose between two or more alternatives, none of which is ideal. Typically, strong emotions are tied to the issue and the alternative solutions, and it is not possible to say that one is better than the other. If an ethical dilemma arises and the nurse is involved in the care, the nurse should participate in the decision-making by supporting the patient and helping to get patient information needed for effective decision-making. If the nurse is not involved in the issue, then the nurse should not step in unless the situation is critical or a request is made for the nurse's participation. Some ethical issues may involve the physician or other healthcare provider and not the nurse.

Once the ethical dilemma is recognized, the next step is assessment to get facts so that a decision can be made. What are the medical facts, including information about treatment? What are the psychosocial facts? What does the patient want? Which values are involved, and what is the conflict? Getting this information requires talking to others, including the patient and-if the patient approves-the family, significant others, and other healthcare providers. Neither the nurse nor the physician makes the decision about sharing information with family or significant others, nor do they make the final decision about treatment unless the situation is an emergency and the patient is not able to speak for himself or herself. The treatment team provides recommendations to the patient. Sometimes, the nurse may have concerns that the treatment team does not recognize the presence of an ethical dilemma; in this case, the nurse should discuss this observation with the team. After the assessment is concluded, the information is used to develop a plan to address the dilemma. This requires examining the choices, goals, and views of the involved parties. Options need to be prioritized to guide an effective analysis. If the patient is able and willing to participate in the decision-making process, the patient needs to be involved. The final decision must be one that the patient accepts. During implementation of the decision, the nurse should be the patient's advocate, even if the nurse does not agree with the patient's final decision.

Professional Ethics and Nursing Practice

Ethics is a part of any profession, and in nursing, professional ethics is part of daily practice. In an important report about nursing education, Benner and colleagues (2010) emphasized that nursing education needs to focus more on ethical conduct. Students need to develop skills to respond effectively to ethical issues, which may involve responding to situations in which errors occur. “Nurses need the skill of ethical reflection to discern moral dilemmas and injustices created by inept or incompetent health care, by an inequitable healthcare delivery system, or by the competing claims of family members or other members of the healthcare team” (Benner et al., 2010, p. 28). It is not easy to find the “right” perspective on ethics in professional roles and in the care provided. Each nurse works to find this perspective and determine how it meshes with the nurse's personal views. This is the potential dilemma between the nurse's view of ethical behavior and the patient's view.

With the increased emphasis on healthcare quality improvement, it is important to recognize that ethical and legal issues are related to quality care, particularly when errors occur. There is discussion in other chapters about staff stress and how this impacts care. Involvement in an error can cause stress, or stress may have been a factor in causing the error. Moral disengagement is “the process that involves justifying one's unethical actions by altering one's moral perception of those actions” (Hyatt, 2017, p. 15, as cited in Bandura, 1999). A common response is displacement of responsibility or shifting of blame-it was not my responsibility; it was someone else's. Why does this happen to staff? One reason may be the work environment is not always healthy, and staff members may have limited energy to deal with issues or may withdraw from taking responsibility. Another reason may be staff want to do what is expected (an ethical action), but there are barriers in the HCO to achieving this, such as staff levels and competencies, rules and policies, time issues, and so on. This leads to moral distress, which can result in staff experiencing anger, hopelessness, depression, and compassion fatigue. This can become a cycle in that moral distress may result in more moral distress for the organization, resulting in a hostile work environment, staff and management passive-aggressive behavior, increased problems with errors, staff working around the system (discussed in more detail in content about quality improvement), and staff retention problems (Hyatt, 2017). It is important that nurses and HCOs support a healthy work environment to prevent or reduce these problems that negatively affect care improvement and impact effective decision-making.

American Nurses Association Code of Ethics

Professional organizations, such as the American Nurses Association (ANA), have developed ethical guidelines. The Guide to the Code of Ethics for Nurses: Interpretation and Application (ANA, 2015) is the primary source or guide for nurses when ethical issues are encountered to help nurses understand the intent of the ethical guiding principles and their application. A nursing code of ethics was first discussed in the United States in 1896, but it took a long time before the code was developed and implemented. Several editions of this code have been issued to ensure that the content and expectations stay current with practice and healthcare issues (Fowler, 2015). The Code of Ethics may change over time, but it has consistent elements based on the four ethical principles mentioned earlier in this chapter, an emphasis that has been retained from one edition to another.

Obtaining a registered nurse (RN) license and entering the profession requires that nurses meet the professional roles and responsibilities identified by the nursing profession. Ethics is a part of professionalism. Self-reflection, or the ability to look at a variety of possibilities and consider pros and cons, is also important. It is part of critical thinking and particularly important when there does not seem to be one right answer, which is the case when an ethical dilemma is experienced.

Reporting Incompetent, Unethical, or Illegal Practices

Every nurse, regardless of degree preparation or position, has a responsibility to report incompetent, unethical, or illegal practices to the nurse's state board of nursing (National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN), 2021; ANA, 2015; Burman & Dunphy, 2011); however, reporting requirements vary from state to state. Nurses can report concerns about other nurses to the state board of nursing, but others, such as employers, consumers, and family members, can also report concerns. Each state's nurse practice act (state law) serves as a guide for the nurses in the state. This law should be familiar to all licensed nurses in the state. Nurse practice acts vary from state to state because each act is considered part of a state's laws and is not administered at the federal level, though there are similar issues covered in the practice acts.

State boards of nursing have specific processes and procedures that must be followed regarding making and handling complaints. The source of a complaint remains private. This confidentiality is intended to protect the person who reports the complaint as well as eliminate fear of reprisal that would limit the reporting of complaints. Among the common complaints brought to a state board of nursing are using illicit drugs or alcohol during nursing practice, stealing drugs from an HCO, committing a serious error that might demonstrate incompetence, and falsifying records. It is important to remember that a complaint or an initiative by the board to investigate a nurse does not mean that the nurse is guilty. The legal process that must be followed by the state board provides rights for the nurse, rights that can be used to defend oneself. Any nurse who is informed of a board of nursing complaint or recognizes that such a complaint might be filed should consult with an attorney. This legal advisor should not be the same attorney who represents the nurse's employer; rather, the nurse should retain the services of a personal attorney. Dealing with disciplinary actions is a major board of nursing responsibility. The media, legislators, and policymakers are interested in disciplinary actions that the boards take. A board of nursing must find a balance between protecting the public and protecting the individual nurse's right to practice and the nurse's right to due process.

In some situations, such as when a nurse is identified as possibly using substances (alcohol, drugs), the state board of nursing may offer the nurse the option of entering a program that helps individuals with substance use disorders. This provides nurses with the opportunity to meet specified criteria to maintain their licensure and practice. In this type of situation, the nurse must agree to enter a nondisciplinary program that provides diagnosis and treatment support and agree to monitoring upon return to practice, which often includes regular substance use testing over a specified period. The risk of public knowledge about a substance use disorder may compel a nurse to accept attendance in this type of alternative program. Return to practice or continuation of practice is not guaranteed, and the nurse is carefully monitored to ensure public safety.

| Stop and Consider 1 |

|---|

| RNs are required to report incompetent, unethical, or illegal practices. |

Critical Ethical Issues in Healthcare Delivery

Critical ethical issues change over time due to current issues in healthcare delivery. Three issues that are important today are healthcare fraud and abuse, research ethics, and organizational ethics. They are important to the nursing profession-nurses need to be aware of the issues, speak up when there are concerns about these issues, and demonstrate leadership in healthcare organizations-and they are important to healthcare delivery.

Healthcare Fraud and Abuse

Healthcare fraud and abuse are common. Fraud is a legal term that means a person deliberately deceives another for personal gain. Fraud also has a nonlegal definition, but the focus here is on fraud that involves breaking the law. In health care, it usually involves money and reimbursement. For example, a patient may be charged for care that the patient did not receive or may be charged more than the usual fee. In 2009, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) established the Healthcare Fraud Prevention and Enforcement Action Team (HEAT). Its mission is to prevent and reduce Medicare and Medicaid healthcare fraud. An example of the extent of healthcare fraud is the DOJ charged over 345 people across 51 federal districts, representing the largest initiative in the history of efforts to reduce this type of fraud (DOJ, 2020). The charges represented $6 billion in loss and involved more than 100 doctors, nurses, and other healthcare staff and private and public insurance. A significant portion of the charges are related to digital health fraud.

Because of the ongoing major loss of money, the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) included provisions to increase monitoring and enforcement of laws to prevent fraud (HHS, OIG, 2011). In March 2011, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) began an ambitious project to revalidate all 1.5 million Medicare-enrolled providers and suppliers under the new screening requirements. This major effort was made because of the concern that fraud was increasing. Since the start of this monitoring, many providers have lost their ability to request CMS reimbursement for services, and revalidation is now an ongoing initiative (HHS, CMS, 2022). Typical reasons for providers losing the right to request CMS reimbursement are providers having felony convictions, not being operational at the address CMS had on file, and/or not being in compliance with CMS rules.

Fraud may be committed by physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and other healthcare providers; medical equipment companies; and HCOs. Exhibit 6-1 identifies examples of Medicare fraud schemes, which continue to be used. Areas of health care in which fraud is most prevalent include psychiatric care, home healthcare, long-term care, and large corporate healthcare organizations, though it can occur in any type of healthcare.

| Exhibit 6-1 Examples of Medicare Fraud Schemes |

|---|

|

Ethics and Research

Research is an area in which complex concerns about ethical and legal issues arise, and there is a history of ethical problems in research. The most well-known historical example in which research participants were abused was the Nazi medical experiments in World War II (Europe), and after the war, it had a major influence on global concerns about ethics and led to international ethical guidelines. Major examples of research ethical concerns in the United States are the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, in which African American men with syphilis were not treated so that researchers could observe the course of the disease (1932-1972), and the Willowbrook Study, in which residents of an institution for children with mental disabilities were deliberately infected with hepatitis (the mid-1950s to the early 1970s). In the late 1970s, recognition of these major research abuses in the United States led to reforms and the creation of legal guidelines that now must be followed by all healthcare researchers. The Belmont Report (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1979) identified the key concerns and the need to implement ethical principles when conducting and reporting research. Exhibit 6-2 contains an excerpt from The Belmont Report's introduction.

| Exhibit 6-2 The Belmont Report |

|---|

| On September 30, 1979, the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research submitted a report entitled “The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research.” The report emphasized the basic ethical principles underlying the acceptable conduct of research involving human participants. These principles-respect for persons, beneficence, and justice-are now accepted as the three quintessential requirements for the ethical conduct of research involving human participants. |

The report also described how these principles apply to the conduct of research. Specifically, the principle of respect for persons underlies the need to obtain informed consent; the principle of beneficence underlies the need to engage in a risk-benefit analysis to minimize risks; and the principle of justice requires that research participants should be selected fairly. As was mandated by the congressional charge to the Commission, the Belmont Report also clarified a distinction between “practice” and “research.” In summary, the text of the report is divided into two sections: (1) boundaries between practice and research and (2) basic ethical principles. Data from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). (1979). The Belmont report. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/ |

Research: Informed Consent

Participation in research must include informed consent, and there are rules regarding how this consent must be obtained. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is a key resource for information about research consent. Some of the information that is required in the consent process includes the nature and purpose of a research intervention; potential risks, discomforts, and benefits to the patient; alternative treatments; compensation if injury occurs; compensation for participating in a study (if offered by the study); and a clear statement of how the participant may withdraw at any time without any negative impact on the participant as a patient.

The institutional review board (IRB) is an organization's committee or department that ensures that the research process meets ethical and legal requirements in protecting participants in biomedical or behavioral research. Hospitals, universities, and other organizations that conduct research have IRBs. The following passage describes the differences between patient care and research, which can sometimes be confused and continues to apply to research activities:

“While recognizing that the distinction between research and therapy is often blurred, practice is described as interventions that are designed solely to enhance the well-being of an individual patient or client and that have a reasonable expectation of success. The purpose of medical or behavioral practice is to provide diagnosis, preventive treatment, or therapy to particular individuals. The Commission distinguishes research as designating an activity designed to test a hypothesis, permit conclusions to be drawn, and thereby to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge (expressed, for example, in theories, principles, and statements of relationships). Research is usually described in a formal protocol that sets forth an objective and a set of procedures designed to reach that objective. The report recognizes that ‘experimental' procedures do not necessarily constitute research, and that research and practice may occur simultaneously. It suggests that the safety and effectiveness of such ‘experimental' procedures should be investigated early, and that institutional oversight mechanisms, such as medical practice committees, can ensure that this need is met by requiring that ‘major' innovation[s] be incorporated into a formal research project” (HHS, 2017; 1993; 1979).

In healthcare research, participants may be exposed to multiple risks, typically classified as physical, psychological, social, and economic risks. In 2016, new federal regulations were approved focusing on the procedural needs for submitting research sample registration and summary of study result information, including adverse event information, from clinical trials of drug products and device products (HHS, NIH, 2022). These regulations became effective in January 2017. The purposes of this initiative focused on protecting participants in clinical trials and ensuring rapid, accurate sharing of information about studies, improving public access to research information. The regulations are complicated and require organizations (healthcare, academic, and so on) and researchers to be more vigilant about sharing information. If this is not done, penalty fees may be applied, and organizations and researchers may lose research funding.

Research: Risk of Physical Harm

Some medical research is designed only to more carefully measure the effects of therapeutic or diagnostic procedures applied during treatment for an illness-clinical trials (HHS, NIH, 2016). This research may not involve any significant risks beyond what would be expected for the medically indicated interventions. Research designed to evaluate new drugs or procedures, however, might present more than minimal risk and sometimes can cause serious or disabling harm. These types of studies may lead to greater participant physical risk and thus would be reviewed by the IRB and require informed consent. Some of the adverse effects that result from medical procedures or drugs may be permanent, but most are typically transient. Procedures commonly used in medical research usually result in no more than minor discomfort (for example, temporary dizziness, the pain associated with venipuncture), but it is important that this is recognized and understood during the process and by all relevant parties.

Research: Risk of Psychological Harm

Participation in research may result in undesired changes in thought processes and emotions (for example, episodes of depression, confusion, or other cognitive effects resulting from the drugs used, feelings of stress, guilt, and loss of self-esteem). These changes may be transitory, recurrent, or permanent. Most psychological risks are minimal or transitory, but IRBs should be aware that some research has the potential to cause serious psychological harm, and this should be considered in informed consent. Stress and feelings of guilt or embarrassment may occur simply from thinking or talking about one's own behavior or attitudes on sensitive topics, such as substance use, sexual preferences, and violence. These feelings may be aroused when the research participant is interviewed or when completing a questionnaire. Stress may also be induced when researchers manipulate the participant's environment-such as if emergencies or fake assaults are staged to observe passerby responses; lighting is changed, or noise is used; and so on. More frequently, however, IRBs assess the possibility of psychological harm when reviewing behavioral research that involves an element of deception, particularly if the deception includes false feedback to the research participants about their own performance.

Invasion of privacy is a risk of a somewhat different character. In the research context, the research usually involves either covert observation or participant observation of behavior that the participants consider private. The IRB must decide the following about the study: (1) Is the invasion of privacy acceptable considering the participants' reasonable expectations of privacy in the situation under study? (2) Is the research question of sufficient importance to justify the intrusion? The IRB should also consider whether the research design could be modified so that the study can be conducted without invading privacy.

Breach of confidentiality is sometimes confused with invasion of privacy, but it is a different problem. Invasion of privacy concerns access to a person's body or behavior without consent; breach of confidentiality concerns safeguarding information that has been given voluntarily by one person to another. Some research requires the use of participants' hospital, school, and/or employment records. Access to such records for legitimate research purposes is generally acceptable if the researcher protects the confidentiality of that information, the participant is informed of this access, and the participant provides permission. The IRB must be aware, however, that a breach of confidentiality may result in psychological harm to individuals (in the form of embarrassment, guilt, stress, and so forth) or in social harm.

Research: Risk of Social and Economic Harm

Some invasions of privacy and breaches of confidentiality may result in embarrassment within one's business or social group, loss of employment, or criminal prosecution-all representing a risk of social and/or economic harm. Types of information that have a higher concern for sensitivity are alcohol or other substance use, mental illness, illegal activities, and sexual behavior and identity. Some social and behavioral research may yield information about individuals that could label or stigmatize the participants. Confidentiality safeguards must be effective in these instances. The fact that a person has participated in HIV-related drug trials or has been hospitalized for treatment of depression could adversely affect the person's present or future employment, political campaigns, standing in the community, and so on. A researcher's plans to contact these individuals for follow-up studies should be reviewed with care and approved in the IRB process. Participation in research may result in additional actual costs to individuals, such as transportation, childcare, and time off from work. Any anticipated costs to research participants should be described to prospective participants during the consent process.

Nurses should be concerned about these issues for several reasons. First, nurses conduct research, and they must follow the same rules as anyone else who uses human participants or even animals in a study. Second, nurses may assist in getting informed consent, data collection, and other aspects of a research study. Nurses also work in areas where clinical research is ongoing. In these situations, the nurse must continue to act as the patient advocate; ensure that the patient's rights are upheld; and be aware of the study, which should provide as much information as possible to help the nurse understand the patient's care experience and the study procedure.

Some student projects are also assessed to see whether an IRB review is needed for the project. Faculty are responsible for guiding students to determine if the school's (college, university) IRB committee should make the decision about the need to complete the IRB written requirements or, if a clinical site is used for the project, the need for the involvement of an HCO's IRB.

Knowledge and application of the ethical principles related to research need to be part of practice whenever nurses are directly or indirectly involved in research. Exhibit 6-3 identifies key points of the Code of Federal Regulations related to research that might affect nurses and nursing care.

| Exhibit 6-3 Code of Federal Regulations |

|---|

|

Staff are responsible for ensuring patient safety, and this includes participation in research. Even staff who are not directly involved in a research project should be alert to patient needs. Figure 6-2 provides an overview from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services of research misconduct and what might be required of staff in this type of situation.

Figure 6-2 You Suspect Research Misconduct. Now What?

An infographic on handling and reporting research misconduct.

The first section outlines steps if you suspect research misconduct. It includes: Avoid confrontation to prevent retaliation. Keep notes that document all communications related to the misconduct. Educate yourself about your institution's misconduct policy or contact the U.S. Office of Research Integrity, O R I. Seek support from trusted individuals, and Consult your Research Integrity Officer, R I O, for guidance. The second section outlines the challenges and benefits of reporting misconduct in a research environment. It highlights common concerns such as potential impact on careers, both of the accused and the reporter, and possible repercussions within the lab. Conversely, it also emphasizes the positive outcomes, like preserving the integrity of scientific data, correcting the literature, ensuring responsible allocation of research funding, and maintaining public trust in science. The third section outlines recommendations for reporting research misconduct, emphasizing the following points: Be Specific: Provide the Research Integrity Officer, R I O, with specific examples of the suspected misconduct, detailing the context, for example, manuscripts, presentations, grant applications. Be Available: Aid the R I O by identifying and examining evidence, explaining how the research was compromised, through falsification, fabrication, or plagiarism, and participating as a witness. Be Prepared for Silence: Be aware that institutional policies may restrict your access to confidential information about the research misconduct proceedings. Be Patient: Understand that the process to resolve allegations of research misconduct can be lengthy and demands significant effort and time. Text at the bottom reads, Make an informed decision, if you want to talk anonymously or report misconduct, contact O R I at 240-453-8800 or ask O R I h h s commercial at symbol dot g o v. There are several icons and social media links at the bottom.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources (HHS). Office of Research Integrity (ORI). You suspect research misconduct. Now what? https://ori.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2017-12/9_Suspect_Misconduct.pdf

Organizational Ethics

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there were serious breaches of organizational ethics that provided the nursing profession with important learning experiences and recognition of the need to be vigilant and ensure HCOs and practices followed ethical standards. As a result of these experiences, in 1994, the federal government recognized a loss of 10% of its total healthcare expenditures to fraud, which was equivalent to $100 billion (U.S. House of Representatives, 1994). This was a shock to the healthcare system and to healthcare professionals. Because of increasing corporate healthcare fraud and abuse of patients, the CMS, through legislation, now requires that HCOs reimbursed for Medicare and/or Medicaid services meet certain compliance conditions to better ensure the HCO maintains appropriate organizational ethics. Because it is rare that a hospital does not receive this type of reimbursement to cover care provided to some of their patients who are Medicare or Medicaid enrollees, this mandate applies to most hospitals. Organizations must identify a compliance officer who audits and monitors actions taken to detect, correct, and prevent fraud. Staff must know how to report concerns related to ethical behavior and potential fraud, and they must be provided with education about these critical issues. Reporting methods should ensure privacy for staff, and they should not be penalized for reporting. The federal government established these requirements because it does not want patients abused. In addition, the government is concerned about the major loss of funds that has occurred because of fraud.

Whistleblowing may be part of fraud and abuse situations. This action occurs when a person who works for an organization that is committing fraud and abuse reports these activities to legal authorities, sharing extensive information that would be difficult for the authorities to obtain on their own. The False Claims Act, a very old law, protects whistleblowers. This law was passed during the Civil War and amended in 1982 to further shield whistleblowers, protecting them from being sued and being fired or otherwise penalized by their employer for reporting the organization or staff within the organization. If the federal government pursues the case and recovers funds, the whistleblower receives a portion of the funds. Anyone can be a whistleblower, but the person must have information that could not be obtained otherwise or information that was not public knowledge (such as that reported in a newspaper). This type of legal action is complicated and very difficult to resolve.

An example of whistleblowing occurred in an academic health center in 2016, involving an RN as the whistleblower (Becker's Hospital Review, 2016). The hospital was not following the standard procedure to ensure that steps were taken to sterilize equipment used for bronchoscopy, which may have led to infections in 100 patients. This also had an impact on monitoring quality improvement. A nurse tried to get hospital staff to address the problem but was unsuccessful. The nurse then went to an attorney, and the result was a whistleblower civil suit. This case contains many ethical and legal aspects, such as a cover-up, lack of response to staff feedback about quality care, lack of concern about quality care, harm to patients, and subsequent legal ramifications. It also demonstrates that nurses take steps to ensure quality and advocate for patients-ethical and legal issues are interconnected in this example.

| Stop and Consider 2 |

|---|

| Nurses and other healthcare professionals have participated in unethical and illegal practices. |

Legal Issues: An Overview

Legal issues are a part of every nurse's practice. State boards of nursing identify situations for which licensure could be denied. You can search your state board of nursing's website for this information. Licensure itself is a legal issue that is implemented through the legal system. The nurse practice act in each state is a state law. The following are some examples of nursing-related legal issues:

- When the nurse administers a narcotic medication, specific procedures must be followed to ensure that patients receive medications per healthcare provider orders and the narcotic drug supply is monitored (counted) to make sure the amounts are correct based on use in patient care. If there are errors, it may mean that a criminal act occurred-someone removed a narcotic or controlled drug with no right to do so.

- Restraining a patient without a physician's order or not in accordance with the requirements in the patient care order or healthcare organization policy can be considered assault and battery.

- Falsifying medical records can have adverse legal consequences.

- Accessing an electronic medical record for a patient who is not in a specific nurse's care can be questioned.

- Inadequate supervision of patients that leads to serious patient outcomes, such as falls with injury or suicide, may have legal consequences.

Critical Terminology

The nurse may encounter the following legal terms as part of nursing practice:

- Assault: This is a threat or use of force on another individual that causes the person to feel reasonable apprehension about imminent harmful or offensive contact. An example is threatening to medicate a patient if the patient does not comply with treatment. This type of threat is not uncommon in behavioral or mental health care but should not be made.

- Battery: This is the actual, intentional striking of someone, with intent to harm, or acting in a rude and insolent manner even if the injury is slight. An example of battery is conducting a procedure, such as starting an intravenous line, without asking the patient. If this is an emergency and the patient's life is at risk or if there is a risk of serious damage and the patient is not able to provide consent, the event would not be considered battery.

- Civil law: This type of statute (law) focuses on private rights.

- Criminal law: This type of statute deals with crimes against the public and members of the public, with penalties and related legal procedures, such as charging, trying, sentencing, and imprisoning defendants convicted of crimes.

- Doctrine of res ipsa loquitur: This is a doctrine of law in which a person is presumed to be negligent if the person or an organization/employer had exclusive control of whatever caused the injury, even though there is no specific evidence of an act of negligence, and without negligence, the accident would not have happened.

- Emancipation: A child is a minor and, therefore, under the control of his or her parent(s)/guardian(s) until the child attains the age of majority (18 years), at which point he or she is an adult. In special circumstances, a minor can be freed from control by the minor's parent/guardian and given the rights of an adult before turning 18 (emancipated). In most states, the three circumstances under which a minor becomes emancipated are (1) enlisting in the military (requires parent/guardian consent), (2) marrying (requires parent/guardian consent), and (3) obtaining a court order from a judge (parent/guardian consent not required). A minor can also petition the court for this status if financial independence can be proven and the parents or guardian agree. An emancipated minor is legally able to do everything an adult can do, except actions that are specifically prohibited if one has not reached the age of 18 (such as buying tobacco or drinking alcohol). From a healthcare perspective, emancipated minors can sue and be sued in their own name, enter contracts, and seek or decline medical care.

- Expert witness: This is a person with specific expertise and knowledge who can provide testimony to prove or disprove the standard of care that is used to support a malpractice case. A nurse may serve as an expert witness for nursing care but not for medical care issues. Typically, the nurse is also a specialist in the specific area of care addressed in the legal case. For example, for a case involving the death of a newborn in a neonatal intensive care unit, the expert witness should be a neonatal nurse. During the case, the expert nurse witness will be asked about accepted standards of care related to the type of care that was required.

- False imprisonment: Confinement of a person against his or her will is against the law. This can happen in health care-for example, when a patient wants to leave the hospital but is retained (an exception is when a patient is legally committed for medical reasons or held for legal reasons by law enforcement or courts); when a patient is threatened or the patient's clothes are taken away to prevent the patient from leaving; or when restraints are used without written consent, appropriate physician order, or a sufficient emergency reason.

- Good Samaritan laws: These are laws that protect a healthcare professional from being sued when providing emergency care outside a healthcare setting. The provider must provide the care in the same manner that an ordinary, reasonable, and prudent professional would do in similar circumstances, including following practice standards. An example is a nurse who stops on the highway to assist an accident victim should follow the expected standard for providing care to a victim with a severe burn to maintain respiratory status under emergency conditions.

- Respondent superior: An employer is responsible for the actions of employees in the course of employment. This doctrine allows someone-for example, a patient-to sue the employee who is accused of making an error that resulted in harm, and the patient may also sue the employer, the HCO, such as a hospital or clinic, because the employer is responsible for supervising the staff member. For example, if a nurse administers the wrong medication and the patient experiences complications, the nurse may be sued for the action. The hospital may also be sued for not providing appropriate education regarding medications and medication administration, pharmacy errors, not ensuring that the nurse received medication education, and/or not providing proper supervision. Typically, in such legal actions, multiple persons and organizations may be sued.

- Standards of practice: Standards represent minimum guidelines identified by the profession (local, state, national) and HCO policies and procedures. Expert opinion, literature, and research may also be used as standards. Healthcare standards are used in legal situations to assess negligence in malpractice actions. (See other chapters in this text that include additional information on standards.)

- Tort: This is a civil wrong for which a remedy may be obtained in the form of damages. An example of a tort that is most relevant to nurses and other healthcare providers is negligence, an unintentional tort.

Malpractice: Why Should This Concern You?

Negligence may occur in nursing practice-for example, medication errors, inadequately providing the patients with access to a call light when the patient needs help, a lack of assessment of risk for falls, failure to prevent falls, and failure to implement appropriate interventions when required. Another example of negligence is failure to communicate information that affects care, which encompasses situations such as not documenting care provided or response to care; not contacting the physician with information that would inform the physician of the need for a change in treatment; and failing to document, such as vital sign monitoring data, changes in status, assessment of wound sites or skin status, or malfunctioning intravenous equipment. Negligence may also include inadequate patient teaching, inadequate monitoring and maintenance of medical equipment, lack of identification of an allergy or not following known information about allergies, failure to obtain informed consent, and failure to report another staff member to supervisory staff for negligence or practice problems. All these examples can lead to malpractice suits.

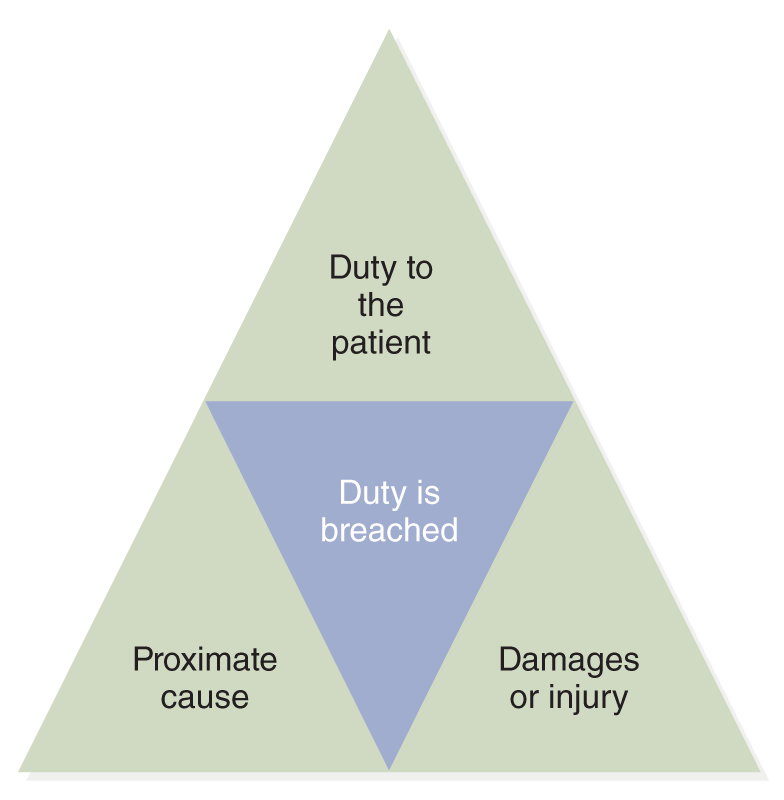

Malpractice is an act or continuing conduct of a professional that does not meet the standard of professional competence and results in provable harm to the patient. Anyone can sue if an attorney can be found to support the suit; however, winning a lawsuit is not easy. Often, lawsuits are settled outside of court to reduce costs and prevent negative publicity; in such a case, even if the patient would not have won the lawsuit, the patient may still receive payment of damages. For a patient or family to be successful with a malpractice lawsuit, the following criteria must be met:

- The nurse (or any person being sued) must have a duty to the patient or a patient-nurse professional relationship. The nurse must have provided care to the patient or been involved in the patient's care.

- The duty must have been breached. This is called negligence, or the failure to exercise the care toward others that a reasonable or prudent person would do under similar circumstances. Any of the following could be used as proof: state nurse practice act, professional standards, healthcare organization policies and procedures, expert witnesses (RNs, preferably in the same specialty as the nurse sued), accreditation and licensure standards, professional literature, and research evidence.

- Thebreach of dutymust be the proximate (foreseeable) cause or the cause that is legally sufficient to result in liability harm to the patient. There must be evidence that the breach of duty (what the nurse is accused of having done or not done, based on what a reasonable or prudent person would do given the circumstances, such as what other nurses would have done in a similar situation) led directly to the harm that the patient is claiming. Since there may be other causes of harm to the patient that have nothing to do with the breach of duty. It is important to understand what occurred.

- There are damages or injuries to the patient. What were the damages or injuries? Are they temporary or permanent? What impact do they have on the patient's life? These questions and many more will be asked about the damages and injuries. If the lawsuit is won, this information is also used to assist in determining the amount of damages that will be awarded. Although the plaintiff (the person suing) identifies an amount when the lawsuit begins, the final amount awarded may be different.

These four malpractice elements are illustrated in Figure 6-3. The plaintiff's attorney must prove that each of these elements exists for the judge or the jury to agree to the plaintiff's case and the plaintiff's awarded damages. The nurse's attorney will defend the nurse by trying to prove one or more elements do not exist in the case. If even one element is missing, malpractice cannot be proven.

Figure 6-3 Elements of malpractice

A triangular diagram with three sections, each representing a critical element of malpractice.

The top segment is labeled duty to the patient, the middle segment reads duty is breached, and the bottom segment includes proximate cause on the left and damages or injury on the right.

Medical malpractice lawsuits affect healthcare practice and costs. These cases are very expensive to defend, and when the plaintiff wins the case, awards are often very high. As mentioned earlier, even if the healthcare provider does not win the case in a court decision made by a judge or jury, a settlement may still be made, though typically settlements occur earlier in the legal process. Collectively, these issues have prompted many healthcare providers to practice “defensive medicine,” in which physicians may prescribe excessive diagnostic testing and other procedures to protect themselves from lawsuits. This approach increases the costs of care, and if testing or procedures are invasive, this can increase patient risk. Malpractice concerns also increase medical costs because physicians, other healthcare providers, and healthcare organizations must carry malpractice insurance to help cover potential legal costs for malpractice suits. These costs are then passed on to consumers through patient service charges, increasing overall healthcare costs.

Since nurses may get sued, they need to consider purchasing professional liability insurance, but there are pros and cons for nurses obtaining this coverage. Such policies are not expensive for nurses, but the nurse needs to be clear about what the policy offers. A question that could be asked is why nurses would be sued when, typically, they do not have high levels of personal funds to pay settlements. Nurses, however, are sued. The typical focus areas of lawsuits that involve nurses are treatment/care, medication administration, assessment, monitoring, patient rights, abuse, scope of practice, and professional conduct. These examples provide an overview of the high-risk concerns that require special attention by nurses in their practice. Often, the nurse is included in a group that is sued for a specific incident-for example, the physician(s), the hospital, specific staff in the hospital (or any other type of healthcare organization), and others. When a nurse is sued, the nurse should not rely on the nurse's employer's attorneys to provide a defense; instead, the nurse needs an attorney who represents only the interests of the nurse. Professional liability insurance covers these fees. There are also different types of malpractice insurance that can be obtained. Two of the most common types are (1) claims-made coverage, which includes only incidents that occur and are reported during the policy's effective period, and (2) occurrence coverage, which provides protection for an incident that took place while the policy was in effect even if the claim was not filed until after the policy terminated. When accepting a job, the nurse should explore the pros and cons of carrying personal, professional malpractice/liability insurance.

As soon as a nurse learns of a possible lawsuit, the nurse should contact an attorney for advice. If the nurse has liability insurance, the nurse contacts the insurer for legal advice, and the insurer may assign an attorney to the case. In addition, the nurse should recognize that at the conclusion of a lawsuit in which the nurse and the employer are sued, the employer might then sue the nurse to reclaim damages to cover some of the employer's expenses for the lawsuit. Nurses must make informed decisions about whether they would rather have their employer's attorney defend them or seek out the services of an attorney who is covered under their own policy, which is required for some malpractice policies, or a personal attorney. In some instances, if the nurse has a personal attorney or an attorney from the nurse's malpractice policy, the institutional legal team will not assist the nurse.

Nursing students are responsible for their own actions and can be held liable for them. Students are not practicing under the registered nurse license of their faculty (Guido, 2020). Because of this, students must not accept assignments or do procedures for which they are not prepared. It is also critical that students discuss these situations with faculty or staff if faculty are not available rather than acting without guidance.

| Stop and Consider 3 |

|---|

| Nurses may be sued. |

Examples of Issues With Ethical and Legal Implications

Ethics and legal issues are often interrelated. The following section highlights some of these issues, such as privacy, confidentiality, informed consent, rationing care, various patient legal decisions and documents, organ transplants, assisted suicide, and the use of social media. These issues relate to nurses and nursing care. Other content in this text discusses diversity, health equity, and inclusion, which also have ethical and legal implications.

Privacy, Confidentiality, and Informed Consents

Patients have the right to privacy, and this affects multiple situations that might occur during the care process, including during assessments and examinations. When patients are told about their condition, this should be done in a private area. Patient rounds are discussed in this text, and during rounds, privacy is difficult to maintain, particularly when the patient shares a patient room, but we need to do what we can to maintain privacy, such as using curtains to separate the patient areas and speaking in lower tones. Privacy is associated with confidentiality and informed consent.

Confidentiality is an issue that is relevant in practice every day. We need to ensure, when possible, that patient information is shared only with those the patient approves or as required for treatment, such as the treatment team. HIPAA has had a major impact on information technology and patient information (HHS, 2017). Nurses are required to follow this law to protect patient privacy and confidentiality. Patients are informed about HIPAA when they enter a hospital, visit another type of healthcare facility for care, or receive outpatient care.

Nurses have the responsibility to keep patient information confidential except as required to communicate in the care process and with team members. Patient/person-centered care also implies that patients have the right to determine who sees their information, and this decision must be honored. It is important to remember that patient information should not be discussed in public areas (for example, elevators, cafeterias, hallways) or any place where the information might be overheard by persons who have no right to hear the information. You will encounter patients and family members who are part of your personal life; however, you must remember that what is known about the patient is private and should not be referred to in personal situations. Nurses who work in the community and make phone calls to and about patients using mobile phones in public places can easily forget that their conversations may be overheard.

It is important to remember that patients drive patient privacy. For example, nurses should not assume that patients want family members to have access to the patient's health information. Instead, patients must be asked who can be told about any health information. As a student and as a nurse, you will have access to patient information only for patients for whom you are directly providing care. You must have a reason related to healthcare activity to access patient information. If you do not adhere to these rules, then you are in violation of HIPAA and may be charged with a penalty. Be aware that patients may and do make HIPAA-related complaints to state boards and to educational institutions, in the case of students, about staff or students who do not uphold privacy rules/HIPAA. Patients may also report HIPAA violations to the federal government (HHS, 2021).

Another ethical and legal concern related to confidentiality is consent. Patient care consent occurs when the patient agrees to treatment, and it may be given either orally or in written form. Whenever possible, consent should be informed consent and documented in writing. The patient's physician or other independent healthcare practitioner is required by law to explain or disclose information about the medical problem and treatment or procedure so that the patient can make an informed choice. The patient has the right to refuse the treatment. Failure to obtain informed consent puts the practitioner at risk for negligence.

The requirement to obtain informed consent applies to many nurses. An advanced practice registered nurse (APRN), for instance, needs to get informed consent from patients or ensure this is done prior to performing treatments and procedures following the required policy. By comparison, the nurse who is not an APRN does not have to get informed consent for typical nursing interventions, such as administering a medication, though if the patient refuses the medication, this must be honored. Moreover, this nurse would not be the staff member who obtains patient consent for treatment or procedures, which should be clarified in the healthcare organization's policies and procedures. In some cases, the nurse may ask a patient to sign a written consent form, but in doing so, it is assumed that the patient's physician or other healthcare provider has explained the required information to the patient. If the patient indicates that this conversation did not occur, the nurse must talk with the physician or other healthcare provider involved and cannot have the patient sign the form until the patient and the physician have discussed the specific treatment or procedure. If a nurse is required to ensure the informed consent is documented and fails to do so, the nurse is at risk for negligence.

A second type of consent is consent implied by law. This consent is applicable only in emergency situations when a patient may not be able to give informed consent. If the patient's life is at risk or if major damage or injury to the patient is likely, healthcare providers can provide care. In this case, the assumption is that the patient would most likely give consent if the patient could, based on what a reasonable person would do. Nurses who work in the emergency department may encounter this type of consent situation.

Rationing Care: Who Can Access Care When Needed

The United States rations care but not formally. Rationing may involve the systematic allocation of resources, typically limited resources. In this case, the limited resources are funds to pay for care. Some people receive care, and others do not. Insurers do not cover all care; instead, they influence the care that will be provided based on reimbursement criteria the insurer identifies. If the insurer will not pay for a service, it is unlikely the patient will receive the service unless willing to personally pay. Other forms of healthcare rationing also exist, such as organ donations and transplantation, which require the allocation of funds to perform transplants and the allocation of limited organs, discussed later in this section.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare rationing was an issue. For example, when there is a lack of needed equipment, intensive care beds, or qualified staff, how are decisions made about who will receive care and even if patients can pay for treatment? This was a critical issue and raised stress among consumers, the government, and the healthcare delivery system. When the system was overloaded with patients who had COVID-19, then patients with other healthcare problems did not always receive treatment when needed, or their treatment was delayed. This all represents a concern about allocating healthcare services during times of crisis, with ethical and legal implications and represents a form of rationing.

Advance Directives, Living Wills, Medical Powers of Attorney, and Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders

Advance directives are now part of the healthcare system. This type of legal document allows a person to describe personal medical care preferences. Often, these documents describe the person's wishes related to future end-of-life needs, in which case the document is called a living will. Patients have the right to develop this plan, and healthcare providers must follow it. Because state requirements vary, it is advised that patients ask physicians if they will uphold the patient's decisions about health care. Any advance directives should be part of the patient's medical record and easily accessible to the healthcare provider. End-of-life issues are never simple but should be a critical part of care for these patients.

A medical power of attorney document, a type of advance directive, designates an individual who has the right to speak for another person if that person cannot do so in matters related to health care. Another name for this document is a “durable power of attorney” for health care or a “healthcare agent” or “proxy.” If a person does not designate a medical power of attorney and the person is married, the spouse can make the decisions if the sick spouse is unable to do so. If there is no spouse, the decision would be made by adult children or parents. People should determine the types of care they prefer and how aggressive that care should be with those they designate with their medical power of attorney. The proxy or agent is not forced to follow the patient's instructions if they are not written in a legal document and if there is no written document, a sick person should trust that the proxy or agent will follow the guide discussed.

Interventions that are typically covered in advance directives include (1) use of life-sustaining equipment, such as a ventilator, respirator, or dialysis; (2) artificial hydration and nutrition (tube feeding); (3) do-not-resuscitate (DNR) or allow-a-natural-death (AND) orders; (4) withholding of food and fluids; (5) palliative care; and (6) organ or tissue donation. The DNR and the AND directives are forms of advance directives or may be part of an extensive advance directive. Such an order means that there should be no resuscitation if the patient's condition indicates the need for resuscitation. A physician may initiate a DNR/AND order without an advance directive, but the physician must follow hospital policy and procedures regarding this type of decision. It is highly advisable that this situation is discussed with the patient, if the patient can comprehend, and with the family. The nurse may be present for this discussion but would not make this type of decision. If there are concerns about how it should be handled, the nurse needs to consult the nursing supervisor/manager. If the HCO has an ethics committee, the nurse may consult with the committee. This is typically an interprofessional committee that is prepared to discuss ethical issues staff and patients encounter and may make recommendations but not final decisions.

Palliative care is now an important healthcare issue, and nurses are involved in this care. Ensuring that patients receive the type of care they want requires nurses to understand the patient's needs and goals and then advocate for them. The decision not to receive “aggressive medical treatment” is not the same as withholding all medical care. A patient may still receive antibiotics, nutrition, pain medication, radiation therapy, and other interventions when the goal of treatment is comfort rather than cure. This is called palliative care, and its primary focus is helping the patient remain as comfortable as possible. Patients can change their minds and ask to resume more aggressive treatment. If the type of treatment a patient wants to receive changes, however, it is important to be aware that such a decision may raise insurance issues that will need to be explored with the patient's healthcare plan. Any changes in the type of treatment a patient wants to receive should be reflected in the patient's living will (ACS, 2021).

Organ Transplantation

As mentioned earlier, organ transplantation is a form of resource allocation. Specific criteria are developed for each type of organ donation, and potential recipients are categorized according to criteria to determine who might receive a donation and in what order. Organ transplantation registries are a critical component of this process. Nevertheless, it is not always clear as to who should get a transplant. Many patient factors are considered-such as age; other medical or psychological illnesses; what the person might be able to contribute to society; whether the person is single or married; whether the person has children; comorbidities or other illnesses, such as substance use disorder; and the ability to comply with follow-up treatment-and some of these factors complicate the decision-making process. Organ transplantation is expensive and usually includes long-term medical needs that may not be covered, or only partially covered, by health insurance. This specialized care also requires a patient's commitment to follow the treatment.

Organ donation must occur first so that organ transplantation is possible. Some people designate their willingness to be organ donors while they are healthy-for example, noting this on their driver's license. However, when the time comes to honor this request, family members may be reluctant to consent to it at an emotional time when a loved one has died. Other people may not have identified themselves as organ donors when healthy, but then something happens that makes them eligible to be organ donors, such as an accident. This situation is even more complex, ethically and procedurally. Healthcare providers ask for organ donations, and hospitals have policies and procedures that describe what needs to be done. It is difficult to approach family members and say their loved ones are no longer able to sustain themselves and then ask for an organ donation at the same time. Consideration of organ donations and transplants is influenced by time, a critical element in maintaining organ viability. This complicates the decisions and procedures, which occur when people (patient, donor, family) are stressed and emotional, but also the staff is stressed trying to ensure the timelines are met to allow for healthy transplantation. Nurses do not ask for organ donations but may assist the physician in this most difficult discussion and the required procedures. Later, family members or the patient (if responsive) may want to discuss it further with the nurse.

Assisted Suicide

Assisted suicide is a complex ethical and legal issue, but the nurse's role is very clear: The nurse is not allowed to participate in helping a person end his or her life. In 1997, Oregon passed the first state law pertaining to assisted suicide, the Death with Dignity Act, which allowed terminally ill citizens of Oregon to end their lives through voluntary self-administration of lethal medications prescribed by a physician for this purpose. The law describes who can be involved and the procedure or steps that must be taken. Two physicians must be involved in the decision. As of February 2024, 9 states legalized physician-assisted suicide by passing legislation; 10 have introduced legislation; 2 have altered their legislation; and 3 states are experiencing problems with this healthcare choice (Compassion & Choices, 2024). In other states, this act is illegal. This type of authorization is changing as more states approve this type of care decision. There has also been an increase in countries that allow assisted suicides.

The ANA believes that the nurse should not participate in assisted suicide. The organization bases this position on its Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements (2015). Nurses, individually and collectively, have an obligation to provide comprehensive and compassionate end-of-life care, which includes the promotion of comfort and the relief of pain and, at times, forgoing life-sustaining treatments (ANA, 2019). In a related topic, the ANA also issued a position statement on the withdrawal of nutrition and hydration (ANA, 2016). The nurse should provide expert end-of-life nursing care based on nursing standards.

Social Media and Ethical and Legal Issues: A New Concern

Social media or the use of networking web-based instruments or sites presents nurses with new ethical and legal issues. A critical issue is that social media may lead to problems associated with professional obligations to protect patient privacy and confidentiality. Nurses should not share information about patients or families, including images. It is not sufficient to limit access using privacy settings. The basic rule is simple: Do not share information or images (Barry, 2017). This can be a slippery slope when we are attached to a patient and then share personal information and thoughts about the patient.

This topic has become very important, and organizations such as the NCSBN (2018) and the ANA (2021) have published information on the topic with guidelines for nurses. Many HCOs have also established their own policies on the use of social media that must be followed by students and staff. The ANA Code of Ethics emphasizes the protection of confidentiality of patient information by nurses (ANA, 2015). HIPAA also protects patient information, and educational and healthcare institutional policies outline the legal issues related to discussion or sharing of protected information. With the expansion in the use of online courses, it is important to remember that when patients are discussed in online forums, the same guidelines apply-no specific identifiers should be shared. This should also apply to staff and HCOs-sharing information that can identify a staff person may not be something that staff person would want done-for example, critiquing a staff member or even an HCO.

This chapter presented introductory information about ethical and legal issues in nursing. Nurses must deal with ethical concerns about their patients and encounter numerous issues that could lead to potential legal concerns daily. A healthcare professional cannot avoid ethics or legal issues. A nurse cares for patients, families, and communities, and in doing so, must consider how that care affects the feelings and rights of others. From the time a nurse achieves licensure, the nurse practices under a legal system through the state nurse practice act and other laws and regulations.

| Stop and Consider 4 |

|---|

| Families of patients do not have the right to be given information about their family member without patient permission or legal power of attorney. |