This chapter focuses on working in teams-both nursing teams and interprofessional teams. Throughout this content, when the term” team” is used, it applies to both interprofessional teams and nursing staff teams, unless specified. The term “group” is not used in healthcare organizations (HCOs) as much as “teams,” which are viewed as more cohesive than a group, and they focus more on coordination, collaboration, and communication (Armstead et al., 2016). Nurses are members of interprofessional teams and members of nursing teams, which include nursing staff, such as registered nurses (RN), licensed practical/vocational nurses (LPN/LVN), and assistive personnel (AP).

This is a critical competency for every nurse. This content includes an explanation of the healthcare professions core competency and the Quality and Safety Education in Nursing (QSEN) competency on teams and collaboration, both emphasizing teams and teamwork, focusing on the critical components of effective teams: communication, collaboration, and coordination (IOM, 2003; QSEN, 2023). Incivility is a problem that many healthcare organizations and staff are experiencing, and this behavior leads to ineffective teamwork and has pushed the drive to improve teamwork. In addition, delegation is a part of the daily work for every nurse and part of planning care and teamwork impacting how a team functions. Teams must cope with change and learn to make effective change decisions. Conflict and conflict resolution are issues that all teams face. Power and empowerment are also discussed in this chapter as they relate to staff and teams.

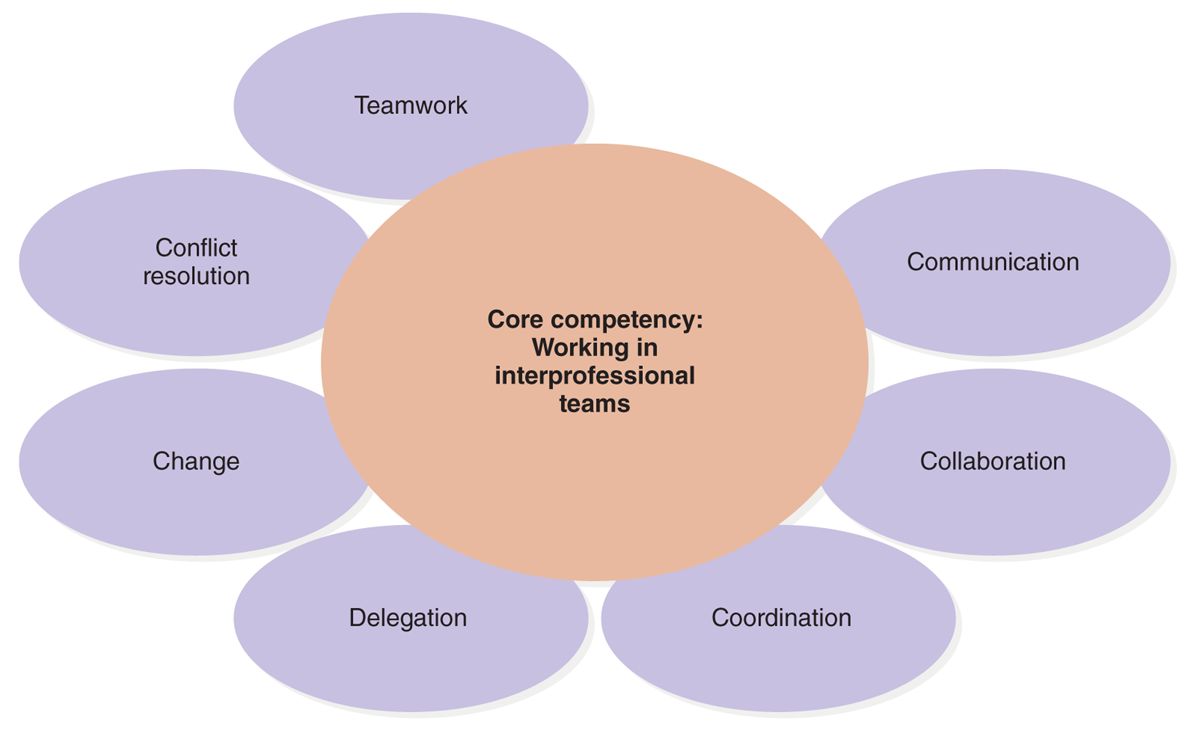

Through its assessment of the U.S. healthcare system, the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2001) described the healthcare system as a system “in need of fundamental change. Many patients, doctors, nurses, and healthcare leaders are concerned that the care delivered is not, essentially, the care we should receive. The frustration levels of both patients and clinicians have probably never been higher, yet the problems remain. Healthcare today harms too frequently and routinely fails to deliver its potential benefits” (p. 1). This description continues to be relevant today. Technology, new drugs, and many other care advances can improve health and health care, but something is wrong with the care delivery models. This set of problems is what drove the need to identify the five healthcare professions' core competencies and, later, the QSEN nursing competencies, focused on effective performance (QSEN, 2022, 2023). This chapter examines the core competency that most directly addresses the need for changes in the care delivery models: work in interprofessional teams. Figure 10-1 highlights the key elements of this competency.

Figure 10-1 Working interprofessional teams: Key elements.

A diagram illustrates key elements of interprofessional teamwork.

The diagram depicts the core competency of working in interprofessional teams at the center. Surrounding this core are key elements: Teamwork, conflict resolution, change, delegation, coordination, collaboration, and communication, each connected to the central competency.

The Core Competency: Work in Interprofessional Teams

The first of the healthcare profession's core competencies is to “provide patient/person-centered care.” This chapter covers the second core competency, to “work in interprofessional teams.” The competency is described as “cooperate, collaborate, communicate, and integrate care in teams to ensure that care is continuous and reliable” (IOM, 2003, p. 4) and relates to the nursing competency: teamwork and collaboration (QSEN, 2022, 2023).

Why is there an emphasis on this core competency? After all, it makes sense that teams are important-why would anyone question this? “Healthcare delivery systems exemplify complex organizations operating under high stakes in dynamic policy and regulatory environments. The coordination and delivery of safe, high-quality care demand reliable teamwork and collaboration within, as well as across, organizational, disciplinary, technical, and cultural boundaries” (Rosen et al., 2018, p. 433). A critical issue is whether healthcare professionals are prepared to participate effectively in teams, particularly interprofessional teams, and the conclusion is they are not. Healthcare professional education takes place in isolation with each healthcare profession providing its own education, with limited reference to other healthcare professionals. The result is that nursing, medicine, pharmacy, and allied health students (for example, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and so on) have limited, if any, contact with one another in their educational programs. Consequently, they have limited knowledge of the roles of other professions and the ways in which they need to collaborate and coordinate care to provide patient/person-centered care (PCC). This is a serious problem because when healthcare professionals graduate and meet their professional licensure requirements, they are expected to work together.

As a follow-up to the 2003 identification of healthcare professionals' core competencies, in 2009, the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) was formed to further address the need for competencies that were not profession specific (IPEC, 2021). The collaborative emphasizes that all HCOs need to develop effective interprofessional teamwork and maintain these efforts. Since 2009, recognizing the importance of interprofessional teams, more education accreditors for different healthcare professions are now including the IPEC competencies in their accreditation requirements. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) is a founding member of IPEC and supports its approaches in the AACN nursing education accreditation program. The endorsement of IPEC content, standards, models, and so on from many healthcare professional accreditation bodies ensures that there is greater integration in healthcare profession education and inclusion in professional literature, such as in textbooks and other professional literature used by students. The IPEC strategic plan identifies its goals and strategies to (IPEC, 2022):

- Serve as the thought leader for advancing interprofessional education.

- Promote, encourage, and support the academic community in advancing IPE efforts.

- Inform policymakers and key influencers about the important contribution IPE makes to addressing the healthcare needs of the nation.

The IPEC website provides resources for faculty related to the IPEC competencies (IPEC, 2023). These competencies also support the World Health Organization's (WHO) perspective on the importance of ensuring interprofessional education to develop and implement effective interprofessional teams.

Nurses need to know how to work on nursing teams that focus on nursing care, but there needs to be awareness that this can lead to isolation and limited recognition of the need for greater reaching out to other healthcare professions and interprofessional teamwork. An example of a concern is nurses tend to focus on the nursing care plan to the detriment of the total plan of care for the patient-a nursing care plan, as opposed to a PCC plan. Nursing education has reinforced this perspective by emphasizing the nursing care plan rather than guiding students to a better understanding of a broader plan of care (Barnsteiner et al., 2007). This is not to say that the same scenario does not exist in other healthcare professions because it does. Nurses also work together on teams related to service and healthcare delivery in general, such as committees and task forces, and some of these are interprofessional. These teams require the same competencies as teams focused on patient care. All healthcare providers should focus on delivering PCC, but one individual healthcare profession cannot provide all the care due to multiple patient needs. Interprofessional teams are best suited to achieve PCC.

| Stop and Consider 1 |

|---|

| All nurses should be competent in serving on interprofessional teams. |

Teamwork

With the increasing complexity of care and concerns about the fragmented healthcare system, interprofessional teams are even more important. In addition, the complex needs of patients with chronic illness, acute care, geriatric needs, and care at the end of life require effective planning to ensure improved outcomes. Different types and complexity of healthcare settings, multiple types of healthcare providers, and the need to share information and planning across settings are dependent on teamwork. The use of interprofessional teams tends to result in improved quality care and a decrease in healthcare costs (IOM, 2003).

Clarification of Terms

The term “interdisciplinary” is used in the initial description of this core competency (IOM, 2003), although now the more widely accepted term is “interprofessional.” In the literature and in practice, nurses encounter other terms that seem similar, such as “multidisciplinary,” which refers to “a team or collaborative process where members of different disciplines assess or treat patients independently and then share information with each other” (McCallin, 2001, p. 420). Multidisciplinary teams focus on how individual team members do their work and encourages sharing of information with others who are providing care. For example, nurses share information about the nursing care plan with physicians and social workers, and vice versa. This typically is what has been done in health care, but it is not what is recommended in this core competency. The descriptor “interprofessional” emphasizes collective action and in-depth collaboration in planning and implementing care. Less emphasis is placed on what individual team members do, and more emphasis is placed on what individual members can do together to contribute to the joint team plan and initiatives. Use of interprofessional teams improves care delivery, for example, these teams:

- Decrease fragmentation in a complex care system.

- Provide effective use of multiple types of expertise (for example, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, allied health, social work, and so on).

- Decrease utilization of repetitive or duplicate services.

- Increase creative or innovative solutions for complex problems.

- Increase learning for team members about different roles and responsibilities, communication and coordination, and ways to better plan care.

- Improve motivation and increase self-esteem in team and individual performance.

- Allow for greater sharing of responsibility.

- Empower team members to speak up.

In summary, the core competency recognizes that “team members integrate their observations, bodies of expertise, and spheres of decision making to coordinate, collaborate, and communicate with one another in order to optimize care for a patient or group of patients” (IOM, 2003, p. 54). The nursing version of this competency is teamwork and collaboration, “function effectively within the nursing profession, offering open communication and respect for optimal patient care” (QSEN, 2023).

Microsystem

Another way to describe the clinical team is to refer to it as a microsystem (Nelson et al., 2008). Clinical microsystems in a healthcare system are “the front-line units that provide most health care to most people. They are the places where patients, families, and care teams meet. Microsystems also include support staff, processes, technology, and recurring patterns of information, behavior, and results” (HHS, 2010). This is the part of the healthcare system where there is interaction among patients, families, and care teams. Clinical staff, support staff, processes, technology, communication and information, staff behavior and attitudes, and outcomes are factors that influence microsystems, which should be patient/person-centered. The major focus is to provide care, and as care is provided, the team needs to consider the elements of quality, safety, reliability, efficiency and innovation, patient satisfaction, and staff morale.

Team Leadership

Teams typically have designated team leaders. For a nursing team, the leader is an RN. Interprofessional teams may have different leaders, and in some cases, the leader may be a nurse. Regardless of who the leader is, all team members are important to the team's success. To be effective, a team leader must first recognize that it is the work of the team that is critical. The leader should not focus on personal success as a leader or on the success of any individual team member. Effective team leadership is demonstrated through the effectiveness of the entire team.

Leaders need to know when to guide, let the team function, and be directive. If the team is on task as planned, the direction is not as critical. In contrast, if the team is floundering and not able to get work done and meet goals, the leader needs to be more active in directing the team, engaging the team to assume more responsibility. Leaders need to encourage and accept team member ideas and actively seek information and ideas from the members. Some of the responsibilities of team leaders are as follows:

- Lead the team-at meetings and as the team works. Represent the team when the organization requires someone from the team to speak for the team and its activities-for example, with management, committee meetings, and so on. Support teamwork and PCC. If the team is interprofessional, ensure that this approach is supported by the team.

- Determine or clarify the team's purpose and operating rules or guidelines with team input. The organization may predetermine some of this.

- Select team members. In many cases, someone other than the team leader or the organization's policies determine who will serve on a team; for example, team members may be assigned to a unit or a particular patient, but the team leader should be involved in this process.

- Orient team members to the team, including coaching and training new members.

- Determine the plan of action with team member participation. After the team reviews information, discusses issues, and arrives at team decisions, the team leader ensures that there is an effective plan of action. If it is a clinical team, keep the focus on the patient(s).

- Determine how to make the team more effective given the time constraints.

- Provide information and resources to the team as needed.

- Update the team as necessary with information from other stakeholders, such as administrative staff, government officials, and so on, as relevant.

- Ensure that the team's action plans are implemented as designed.

- Recognize the team's work as well as the work of individual team members.

- Resolve conflict when it occurs.

- Evaluate the team's outcomes, include input from all team members, and strive for improvement. This information then feeds into the organization's quality improvement program.

- Encourage team learning to improve effectiveness.

- Ensure that required information about team functioning, decisions, and actions is documented, including any formal required reports.

- Accept feedback from team members and others who may be involved.

- Provide feedback to team members and the team.

- Ensure that the team effectively uses collaboration, coordination, communication, and delegation.

Development of Effective Teams: TeamSTEPPS®

The word “team” implies there is a group of people, but how do they develop into a team? To just say, “‘Today this group of staff is a team,' does not mean that the group is functioning as a team. It takes time to develop a team. The term team does not include the letter I, and this is important to note. Teams are about groups of people who work collaboratively, not about individuals. However, it takes effort and time to move a team to a status where it is truly functioning as a team and not as a group of individuals” (Weinstock, 2010). The most common scenario is that team members work in “silos” most of the time and then come together periodically to collaborate and communicate. Unfortunately, this pattern may lead to problems and errors, which may then affect team functioning. The development of an effective team is critical to the success of innovative care methods, such as briefings before handoffs, checklists, and time-outs before surgery, standardized communication methods, such as the situation-background-assessment-recommendations (SBAR), and others. HCOs that just use these methods without working on developing effective teams, such as by applying TeamSTEPPS®, will not be as successful, but using them in combination with teamwork creates a more effective organization and improved care outcomes. These methods are described in this chapter and other chapters.

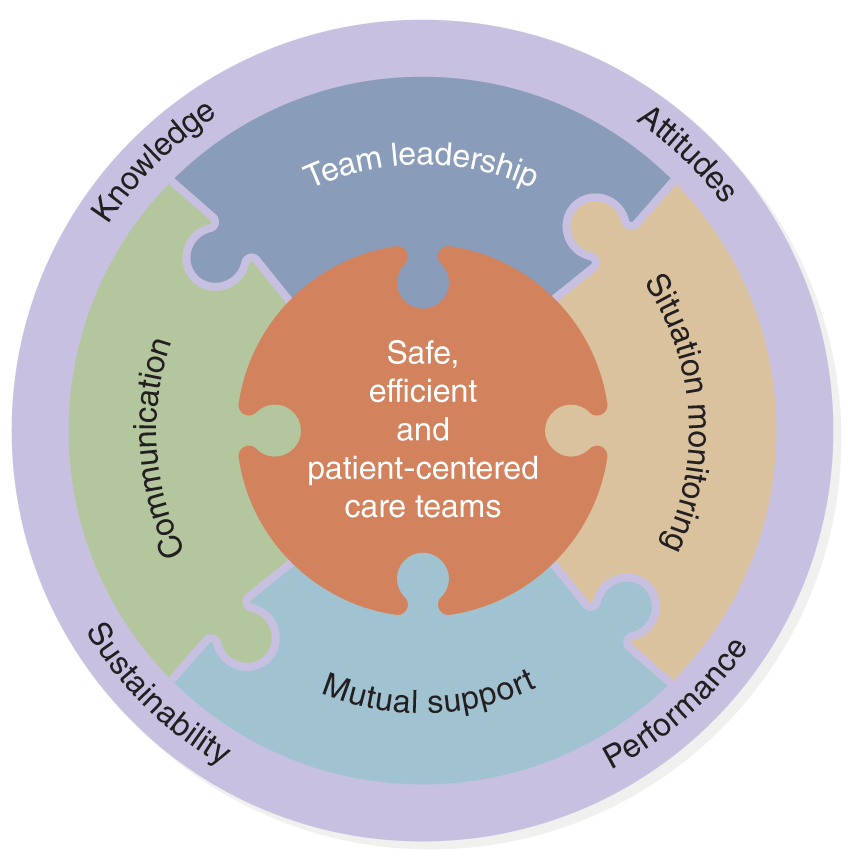

TeamSTEPPS® is an evidence-based teamwork system developed 17 years ago aimed at optimizing patient outcomes by improving communication and teamwork skills among healthcare professionals. It was developed by the Department of Defense, and now the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) assists in making this resource available to HCOs (HHS, AHRQ, 2023a, b). The system and its resources include a comprehensive set of ready-to-use materials and a training curriculum to successfully integrate teamwork principles into any healthcare system. There are many challenges the healthcare system and providers face every day, from care fragmentation to workforce burnout, which means we need proven methods to address patient safety and quality-to move to zero patient harm. The newest version of TeamSTEPPS® has a greater emphasis on focusing on the patient, quality care, and safety. Supporting these needs, the “new version addresses changes in healthcare delivery and learning methods while emphasizing patients' active involvement in their care. The training program aligns with AHRQ's ongoing patient safety efforts, including initiatives aimed at preventing diagnostic errors, healthcare-associated infections, and surgical complications” (HHS, AHRQ, 2023a). Figure 10-2 describes the key concepts in TeamSTEPPS® 3.0 model.

Figure 10-2 TeamSTEPPS®.

A diagram illustrates key elements of TeamSTEPPS.

The diagram features a central circle labeled: Safe, efficient, and patient-centered care teams. Surrounding this are interconnected puzzle pieces labeled: Team leadership, Situation monitoring, Mutual support, and Communication. An outer ring includes additional labels: Knowledge, Attitudes, Performance, and Sustainability.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2023). Pocket Guide to TeamSTEPPS® 3.0. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps-program/curriculum/team/tools/index.html

The following describes the five key TeamSTEPPS® implementation issues (HHS, AHRQ, 2023a):

- Readiness Assessment: This foundational activity comes first and is essential to consider before beginning to implement. It may identify obstacles that must be addressed before a TeamSTEPPS® implementation is likely to succeed.

- Measurement: Measurement should always be informed by specific implementation goals, such as reducing avoidable readmissions, improving safety culture, or achieving other quantifiable and desirable outcomes. You need to make measurement plans at the start of implementation to quantify the extent of the problem and obtain baseline information. It should continue as you assess training activities and the impact of the implementation on outcomes and culture.

- Implementation Planning: Planning should precede implementation and ensure that all implementation activities and measurements are aligned with the implementation's goals.

- Coaching: Coaching supports both the initial use of TeamSTEPPS® tools by trainees and their continued use until they are fully embedded into your organization's work processes and workforce. Thus, coaching supports individual and team behavior change, which contributes to organizational change.

- Change Management: Change management focuses on how to align your implementation plan with your organizational culture and, over time, how to transform your culture to focus on safety and patient needs. Change management ensures change at the organizational and cultural levels.

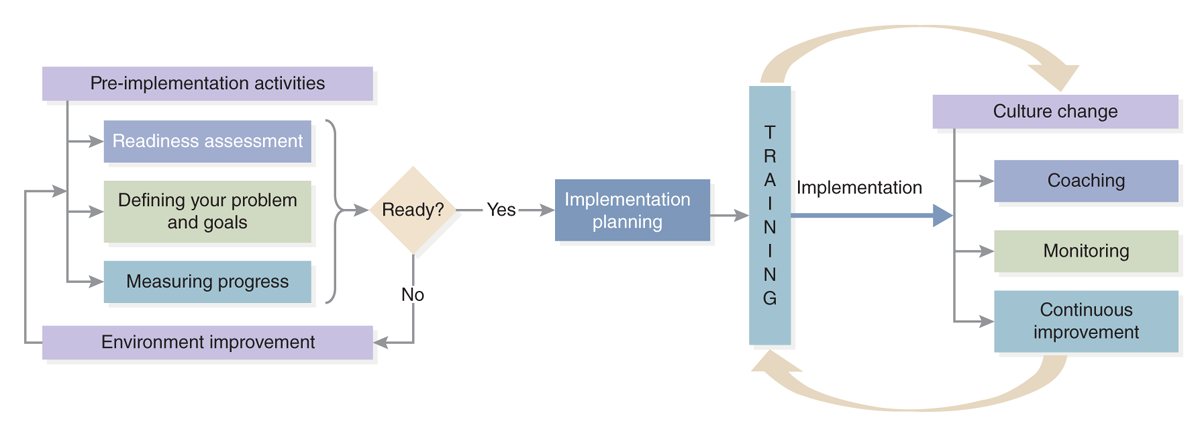

Figure 10-3 describes the TeamSTEPPS® key implementation phases and activities that teams need to consider and apply.

Figure 10-3 TeamSTEPPS® 3.0: Key Implementation Phases and Activities.

A diagram of TeamSTEPPS 3.0.

Pre-implementation activities including readiness assessment, defining your problem and goals, and measuring progress, leading to a decision point labeled, Ready. If no, it loops back to environment improvement. If yes, it moves to implementation planning, followed by TRAINING. After training, it proceeds to implementation, which branches into culture change, coaching, monitoring, and continuous improvement, forming a continuous process.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2023). Key Implementation Phases and Activities. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps-program/curriculum/implement/overview.html

Within a team, members have informal and formal roles, and some members may assume multiple roles at different times as team members interact. Heller defined some of these roles, which continue to apply to teams today (1999, p. 42):

- Coordinator: Pulls together the work of the team

- Critic: Keeps an eye on the team's effectiveness.

- Idea person: Encourages the team to be innovative.

- Implementer: Ensures that the team's functioning is effective.

- External contact: Looks after the team's external contacts and relationships.

- Inspector: Ensures that standards are met.

- Team builder: Develops the team spirit.

In the first report of the Quality Chasm series that examined the status of healthcare quality teams were discussed. Four areas of particular concern were identified that should be used when evaluating team effectiveness (IOM, 2001, p. 132):

- Team makeup, such as having the appropriate team size and composition of members and the ability to reduce status differences (for example, between the nurse manager and staff nurses or between nurses and physicians).

- Team processes, such as communication structure, conflict management, leadership that emphasizes excellence, and clear goals and expectations.

- Nature of team tasks, such as matching roles with knowledge and experience and promoting cohesiveness when work is highly interdependent.

- Environmental context, such as obtaining needed resources and establishing appropriate rewards.

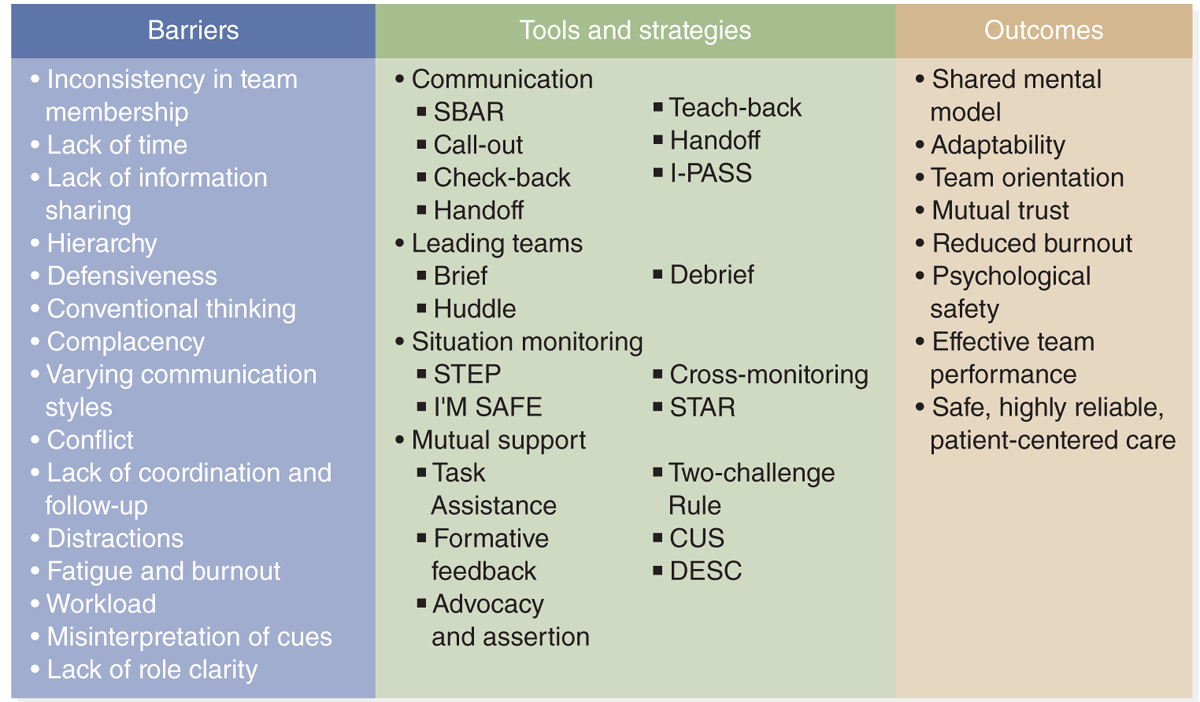

“Effective teams have a culture that fosters openness, collaboration, teamwork, and learning from mistakes” (IOM, 2001, p. 132). However, healthcare delivery tends to overemphasize the personal accountability of healthcare professionals, such as nurses and physicians, and this may negatively affect teamwork. Teams often resort to uncoordinated or sequential action rather than collaborative work, which is required for effective teams. TeamSTEPPS® identifies the following barriers to effective team performance (Figure 10-4). These barriers can be used to identify areas to assess and improve team performance, and the figure identifies tools and strategies and related outcomes.

Figure 10-4 TeamSTEPPS® Barriers to Consider.

An illustration of common barriers, tools, strategies, and expected outcomes for effective team performance in healthcare.

Barriers include inconsistency in team membership, lack of time, lack of information sharing, hierarchy, defensiveness, conventional thinking, complacency, varying communication styles, conflict, lack of coordination and follow-up, distractions, fatigue and burnout, workload, misinterpretation of cues, and lack of role clarity. Tools and strategies include communication with S B A R, call-out, check-back, handoff, teach-back, I-PASS; leading teams with brief, huddle, debrief; situation monitoring with step, I am safe, cross-monitoring, star; mutual support with task assistance, formative feedback, advocacy and assertion, two-challenge rule, C U S, D E S C. Outcomes include shared mental model, adaptability, team orientation, mutual trust, reduced burnout, psychological safety, effective team performance, and safe, highly reliable, patient-centered care.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2023). TeamSTEPPS® 3.0 Pocket Guide. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/teamstepps-program/teamstepps-pocket-guide.pdf

Because there is more focus on quality improvement (QI), teams need to be concerned with QI on a continuous basis. TeamSTEPPS® 3.0 Pocket Guide recommends that team structure is used to support patient safety/quality, particularly in the following areas (HHS, AHRQ, 2023a):

- Communication: Structured process by which information is clearly and accurately exchanged among team members.

- Leadership: Ability to maximize the activities of team members by ensuring that team actions are understood, changes in information are shared, and team members have the necessary resources.

- Situation monitoring: Process of actively scanning and assessing situational elements to gain information or understanding or to maintain awareness to support team functioning.

- Mutual support: Ability to anticipate and support team members' needs through accurate knowledge about their responsibilities and workload.

| Stop and Consider 2 |

|---|

| Teamwork makes a difference in effective teams. |

Improving Team Communication

Communication is important throughout the healthcare system, but it is critical for teams. They cannot function without effective communication. An important role for team leaders is to lead the team's activities, and much of this is done through discussion within the team and with nonteam members. The process of leading discussions can be informal or formal. When the team leader talks with individual team members about team issues and the team's work, this is an informal discussion. In this situation, the leader is seeking an open discussion of issues and sharing of ideas. Such an exchange can help the leader to better understand team members and identify issues that are important to the team's functioning and activities. Informal discussion can also be used for the team members to get to know the leader on a different level. Formal communication typically takes place in meetings and through written or electronic communication methods.

Overview of Communication

All nurses communicate-with other nurses, interprofessional staff, patients, families, and others who may impact patient care. The assumption is that individuals know how to communicate effectively, and this is not always true. Nurses have an ethical mandate to become skilled communicators; doing so is an essential standard of practice as integrated into the profession's standards and code of ethics (ANA, 2021; 2015a). What is important is the effectiveness of this communication. The effectiveness of team communication may also vary, but it is clear communication makes a difference in results, increasing or decreasing errors, improving the work environment, and supporting effective patient-staff relationships.

Individuals have communication styles, and understanding one's style is important. Some people are more passive. Others use more nonverbal communication; some prefer to see important information in writing, and so on. Using professional jargon often creates a barrier, limiting clear communication. This is why using structured communication practices, which are recommended by TeamSTEPPS® 3.0, such as SBAR, call-out, and check-back, is important in reducing communication barriers, particularly when concerned about quality care-safe care (HHS, AHRQ, 2023c; The Joint Commission, 2017). When using these methods, this ensures that healthcare providers use the same terminology and process so that they do not have to take time to figure out the process or what someone else means. What do we need to know about communication to be effective?

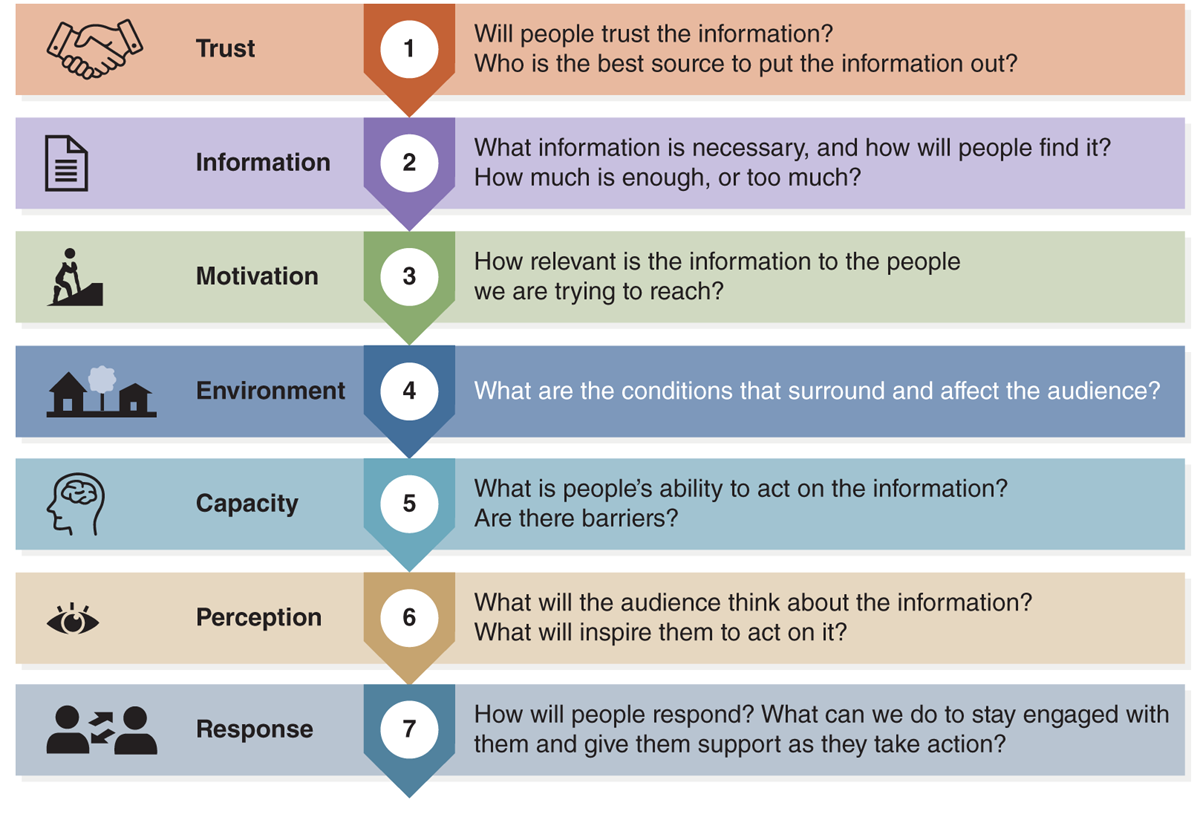

Communication is the sharing of a message between one person, within a team/group or with other teams/groups. It is important to know if the message was received as sent. Interpretation has a major impact on effective communication, and sometimes interpretation confuses or changes the original message. Nonverbal communication also has an impact on the message sent. If a team member verbally affirms commitment to an action, but the team member's facial expression shows a lack of interest (such as no eye contact or a hurried manner), the message of commitment may be viewed as noncommitment. As team members get to know one another, they learn about each other's communication styles, including nonverbal methods. This knowledge confers an advantage in that it can improve and speed up communication. Nevertheless, in some cases, team members may jump to conclusions, and communication may not be clear. The same can be applied to student communication in the classroom or in team discussions. The HHS identifies key considerations that healthcare providers and organizations should integrate in communication about health for individuals, populations, and communities. Figure 10-5 describes these recommendations.

Figure 10-5 Seven Things to Consider When Communicating About Health.

An illustration depicts seven crucial aspects to consider in health communication.

Trust, represented by a handshake icon: Will people trust the information? Who is the best source to put the information out? Information, represented by a document icon: What information is necessary, and how will people find it? How much is enough, or too much? Motivation, represented by a person climbing a hill icon: How relevant is the information to the people we are trying to reach? Environment, represented by house and tree icons: What are the conditions that surround and affect the audience? Capacity, represented by a head with a brain icon: What is people's ability to act on the information? Are there barriers? Perception, represented by an eye icon: What will the audience think about the information? What will inspire them to act on it? Response, represented by two people talking icon: How will people respond? What can we do to stay engaged with them and give them support as they take action?

Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/orr/infographics/communicatinghealth.htm

The Joint Commission analyzed data related to healthcare quality from 2004-2012 and concluded that communication issues were major reasons for deaths related to delays in treatment. An additional review of these issues included data from 2010-2012 and indicated that communication was the third highest root cause of sentinel events (O'Keeffe & Saver, 2014). Concern about communication and errors continue-indicating it is a major factor to consider in improvement efforts (The Joint Commission, 2020, 2017). How one communicates is important; however, not communicating is also a major issue in communication breakdown. Situations that are most at risk for communication breakdown include those involving broken rules or taking shortcuts (work-arounds), mistakes or use of poor clinical judgment, lack of support, incompetence, poor teamwork, disrespect, and micromanagement when someone abuses authority (Maxfield et al., 2005). Effective communication must be frequently monitored and improved.

Relationships and communication between nurses and physicians have long been important healthcare issues because they have an impact on the quality of care and work satisfaction. A small study that included 20 medical and surgical residents examined their attitudes toward nurses (Weinberg et al., 2009). In this study, 19 of the 20 residents shared examples of poor communication or problematic relationships with nurses, but the important result was the residents did not feel such issues presented a problem for patient care because the nurse's role was to follow orders and nothing more. The residents did say that when nurses were knowledgeable and collaborative, such qualities had positive effects on the residents and on patient care-which, of course, contradicts their view of the importance of nurses' contribution to health care. Knowledgeable and collaborative nurses were able to anticipate and respond to needs and then work with residents to identify interventions. This working relationship was part of the residents' positive comments; however, this was not a common experience. This type of result indicated that residents viewed nurses with more education and experience in a more positive light, suggesting there might be a more collaborative relationship formed with these nurses. Because this study focused on residents, transferring these results to experienced physicians is not possible; they represent a different sample, plus it was a small sample. This study also did not examine nurses' views of the medical residents. Despite this early study's limitations, it did identify areas that required further examination to better understand their impact on developing strategies to improve communication. Interprofessional communication and relationships continue to be of concern, and a critical purpose of IPEC is to assist healthcare professionals in developing these competencies, addressing some of the concerns noted in studies, such as the one described.

Ineffective communication is not a one-sided perspective, and the blame for poor communication with nurses cannot just be placed on nurses, medical residents, or any other specific type of staff. Nurses have responsibilities in the communication process, and their role in this partnership is complicated too. There is more of a power struggle today because of the increased number of female physicians, increased number of nurse practitioners, increased nursing autonomy, and decreased perception of physician esteem due to the accessibility of information online that patients and others can review (Nair et al., 2012). It is easy to stereotype and frequently complain about doctors; however, this is not helpful. In a more current study, which was an integrative review of 22 studies about nurse-physician communication, the following was noted: “The challenges in nurse-physician communication persists since the term ‘nurse-doctor game' was first used in 1967, leading to poor patient outcomes such as treatment delays and potential patient harm. Inconsistent evidence was found on the factors and interventions which foster or impair effective nurse-physician communication. . . . Four themes emerged from the data synthesis, namely communication styles; factors that facilitate nurse-physician communication; barriers to effective nurse-physician communication; and interventions to improve nurse-physician communication” (Tan et al., 2017, p. 23). The conclusion from the review was nurse-physician communication continues to be a problem. Other studies and examinations of this issue note that communication breakdown between nurses and physicians has many causes and may lead to errors. Some of these factors are personality clashes, hierarchical structures, different training backgrounds, hectic healthcare settings, and a lack of understanding of colleagues' roles (Clancy & Wehbe, 2022; Manojlovich et al., 2020; Amudha et al., 2018; Farhadie et al., 2017). Strategies that support individual and department communication improvement related to nurse-physician communication include collaborative bedside rounding, inclusivity and teamwork, role model respect, and the use of mindfulness so that one is intentionally aware without interpretation of judgment. Organization and system strategies might include empathy training, stress management, use of structured communication tools, such as SBAR and tools recommended by TeamSTEPPS®, technology, use of team huddles, and staff communication events, such as conferences and lectures on nurse-physician communication (Clancy & Wehbe, 2022). The development and use of innovative strategies indicate that this is recognized now as an important problem and requires improvement in engaging nurse educators, HCO administration, staff educators, staff, and other relevant stakeholders who may be external to the HCO. Feedback and suggestions from patients and families should not be ignored.

Researchers tend to focus on physician-nurse communication, but there are other staff configurations that impact communication in healthcare settings-for example, nurse-to-nurse, nurse-to-assistive personnel, nurse-to-other healthcare professionals, and nurse-to-administrators/managers. These communication relationships and processes are critical to the effective functioning of the healthcare delivery systems, yet problems occur in all interactions. We need to know more about communication from a variety of perspectives.

During the COVID-19 pandemic misinformation about health care and health issues was common and became a barrier to effective health guidance and public response. It was clear we had much to learn about this problem and how to improve public communication. Misinformation, however, is not a problem that only occurs in public health emergencies and has become more and more of a communication problem in health care, but the experiences we have had with the pandemic can assist in decreasing miscommunication. A systematic review of 50 papers on the pandemic and communication (Smith et al., 2023) noted that “Misinformation can erode public trust in science, and preexisting distrust of science, encouraged partially by growing political polarization, can render people more susceptible to misinformation”. This communication and misinformation involve the government, public health authorities, and social media. We need to know about this problem to prevent it from occurring in future public health experiences and to apply it to public health in general. The systematic review concludes that there is a need to include public health experts in intervention design, develop consistent outcome measures, expand intervention studies to visual formats such as testing video-based health misinformation, clearer use of terminology and definitions, test interventions globally (may be differences in types of communication and cultures), and conduct longitudinal research.

We know that effective strategic communication can counteract health misinformation. This requires effective policies, best evidence to guide decisions, improved communication methods, and engagement of all levels of government (local, state, national, and global organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO)). For example, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force helps improve health through evidence-based recommendations on preventive services and addresses this concern. It bases its recommendations on four key principles for using clear communication to counteract health misinformation: (1) emphasize clarity and transparency in communications; (2) use a systematic communications framework; (3) pursue proactive media relations; and (4) engage stakeholders by applying their recommendations about preventive services (Weinstein et al., 2023).

Formal Meetings

Formal meetings are an important part of teamwork, and the team leader or someone designated by the leader usually leads these meetings. Besides participating in team meetings, team members and leaders may participate in a variety of meetings: staff meetings, management meetings, committees, task forces, staff education sessions, and so on. These meetings may be held in a variety of settings. The most common site is a conference room in the healthcare setting. The setting should be private and conducive to fostering communication. Space should be provided for team members to sit and take notes. In clinical settings, telephone access is important, although members should be encouraged to keep interruptions to a minimum-with the increasing use of mobile phones this can be a challenge. Depending on the team's activities, computer/internet access may be important so that information can be readily available.

Another method for conducting meetings today is virtual conferencing, including conference calls, videoconferencing, and internet conferencing, something that became critical for functioning during COVID-19. These methods also require planning and equipment. Members must be informed about access requirements, and technological support may be needed to assist with possible connection problems. Guidelines should be provided to assist staff members attending these meetings so that the team can function effectively, for example, how to ask questions, share documents, and so on. Electronic meetings are different from face-to-face meetings-in style and level of member comfort-but when used frequently, team members adjust and can function effectively. The following guide recommends steps for conducting formal team meetings.

- Planning the meeting: Planning before the meeting is important. Avoid scheduling meetings just to have a meeting. Staff time is limited, and thus, staff may be reluctant to attend or may not be productive in meetings they feel are not worthwhile. Before completing the final agenda, the leader might survey members via email for additional agenda items.

- Premeeting activities: Arrange for meeting space and any technology required. Send out the agenda, any necessary handouts, and minutes from the last meeting. Allow time for this material to be reviewed. Typically, these items are now sent electronically. If there is no one designated as the “minute taker” or secretary, the leader may ask a member to assume this role. If the meeting is using a virtual method, the leader should know how to use the digital system and determine if the meeting will be recorded, how this will be done, and notification that the meeting is recorded prior to the meeting start.

- Meeting time: Meetings should begin and end on time. All members should try to be on time, come prepared, and follow the agenda. The leader should guide the meeting to ensure the agenda is followed. At the beginning of the meeting, minutes should be reviewed and approved-the minutes are the team's documentation. The leader is responsible for making sure all members can participate. In virtual meetings, the leader needs to be aware of members signaling they would like to speak, and members should be told the procedure. If the discussion digresses from the agenda or becomes tense, the leader needs to guide the discussion back to the topic and away from personal reactions. Decisions should be clearly identified. The minutes should reflect action items, persons responsible for those items, and timelines for completion. Any items and actions from a previous meeting should be discussed for updates. Planning and conducting a meeting in an orderly fashion communicates that team member time is valued, and accountability for actions is an expectation.

- Postmeeting activities: Minutes are finalized. The leader and members complete actions that require follow-up or as designated in the team's decision plan timeline. A report of these actions should be addressed at the next meeting or may be sent to members to report progress as needed. It is important not to make team decisions outside the meeting and thus leave some team members out of the process. If a recording of the meeting is available, information about access should be shared with team members.

- Evaluation of meetings: Consider these questions: (1) Did the meeting have a clearly defined purpose (agenda)? (2) Were there measurable outcomes (do the minutes provide data, and were they met)? (3) What was the attendance level? (4) Did members participate in the meeting(s), or was the leader doing all the talking? (5) Is it easy to identify actions taken? Evaluation of meetings should not just be done by the team leader, but team members should also be asked periodically to evaluate meetings.

Another type of meeting that is common among clinical teams is patient care planning meetings. Such meetings may take place daily, each shift, or several times a week. The purpose of these meetings is to assess patient care and determine the patient's plan of care. This type of meeting is typically less structured than the formal meeting (for example, there is no structured agenda or minutes). However, the team leader does need to plan the topics for discussion. The team may develop a common order in which patient issues are discussed. Notes should be kept, although they need not be formal minutes. The team may add changes in the patient's plan of care or other standard clinical documents. The responsibilities noted earlier for team leaders remain the same for the clinical planning team as for other types of teams. In this type of meeting, staff are typically anxious to get their work done, so a focused meeting is critical.

In many hospitals, patient rounds are also used for planning. Staff members attend these rounds as a team, meeting at the patient's bedside to talk with the patient and assess needs. The patient should be an active participant in the rounds supporting PPC, although sometimes the patient does not want to or cannot actively participate. Rounds may be interprofessional (the ideal method) or focused on a specific profession (such as nursing rounds or physician rounds). Patient rounds are discussed in this text in other related content.

Debriefing

Effective teams need to incorporate debriefing as one of their routine communication methods. It can improve team and individual provider performance. Debriefing is defined as “a dialogue between two or more people; its goals are to discuss the actions and thought processes involved in a particular patient care situation, encourage reflection on those actions and thought processes, and incorporate improvement into future performance. The function of debriefing is to identify aspects of team performance that went well, and those that did not. The discussion then focuses on determining opportunities for improvement at the individual, team, and system level” (Edwards et al., 2021). It is important that debriefing is used as a learning tool and not focus on punitive steps to identify individuals who may have made an error. There are three common phases to debriefing (Edwards et al., 2021).

- Setting the stage: To be effective, a debriefing must be conducted in a manner that supports learning. The purpose is not to identify errors and assign blame but to understand why actions and decisions made sense to clinicians at the time. Such a focus increases the probability that positive performance can be reinforced, and new options can be generated for changing performance that was incorrect or below the desired standard. All types of debriefing need to be done in a safe environment, not threatening to participants. Regardless of the length of the debriefing, the tone set by the leader and the leader's management of the discussion are both critical in maintaining participant psychological safety.

- Description or reactions: During this phase, the leader asks team members about their perspectives, important issues, sequence of events, and their reactions to how events occurred in the clinical situation or in a simulation scenario. This supports more effective learning.

- Analysis: In this phase, the leader works with the team to develop the priorities for discussion and considers participant priorities with any other critical safety concerns that were identified during the event. The goal of this phase is to explore clinicians' rationales for observed behaviors, identify and close performance gaps by discussing the pros and cons of actions taken, and identify system issues that may have interfered with performance and could be changed. Team members must be able to be direct with each other during this phase but respectful. Leaders may need to facilitate team members sharing what they were thinking and how they were affected by the actions of others.

- Application: This phase of debriefing identifies and summarizes the main learning points and considers how they can be incorporated into future practice. Explicitly summarizing lessons learned from a clinical event may help team members remember and apply these lessons in the future.

Effective debriefing demonstrates clear communication, roles and responsibilities, understanding of the context of the problem or situation, sharing of workload, and continuous monitoring.

Assertiveness

Assertiveness is a communication style that is often confused with aggression, and, therefore, it may be viewed negatively. Nurses need to learn how to use it effectively. When using assertiveness, a person stands up for what the person believes in but does not push or control others. The assertive nurse uses I statements when communicating thoughts and feelings and you statements when persuading others (Fabre, 2005). Fabre also recommended nurses approach situations calmly, reducing emotional responses. When problems occur, delaying response usually is not helpful; however, if emotions are high, a “cool down” period may be advised. As discussed in other content on communication in the text, we need to consider our audience and use terminology that others can understand.

Another situation related to assertiveness, is nurses need to “break the code of silence” (Fabre, 2005). Nurses are often silent, keeping their opinions to themselves rather than being open with the treatment team and management. This pattern of not communicating most likely is related to low self-esteem in the profession, which has a negative impact-namely, loss of valuable nursing input. Speaking up may be risky, but the results can be worthwhile. It may take time for team members to value one another's opinions and expertise. If done in a professional manner with the goal of collaboration and coordination, over time most team members begin to respect and trust one another; they see value in the team's diversity of multiple healthcare professionals and variety in experience.

Listening

Listening is an important skill to develop. Most people think they listen when they really do not. Effective listening is important when delivering care-to the patient/family/populations/communities and when working in teams and with colleagues. Listening takes practice. There are several barriers to effective listening, such as:

- Anxiety and stress

- Distractions and interruptions

- Too many tasks to do, limited time

- Fatigue and hunger

- Lack of self-esteem

- Anger

- Overwork

- Confusing message

- Reduced trust

- Impact of past experiences on current responses to care

In addition, a team member may not think the team values individual team member's opinions, leading the member to “tune out” or exhibit a lack of concern or respect for the communicator. The opposite can also occur with a team member thinking he or she knows enough and thus does not need to listen.

When you recognize that you are not listening, you should think about what barrier is interfering with your listening. Through this self-examination, you can learn more about the listening process and improve your listening skills-and, in turn, your communication skills. Fabre (2005, p. 80) identifies reasons for listening beyond generally improving communication; it is critical to the effective identification and description of problems:

- Listening exposes feelings-those invaluable but sometimes inconvenient traits that make us truly human.

- Listening jump-starts the solution process because answers may pop up during candid conversations.

- Listening relieves stress. Bottling up thoughts and feelings simply depletes our energy.

- Active listening is more than hearing; it requires communicating to the other person that you are listening.

- Just saying “yes” and “no” is not active listening.

- Paraphrasing communicates that you have listened.

Nurse-physician communication has long been an important topic, probably more so in nursing than in medicine. In addition to the studies mentioned earlier, other studies examined this issue and the impact of collaboration on care, and their recommendations continue to be relevant (Fairchild et al., 2002; Baggs et al., 1999; Higgins, 1999). These studies indicated communication problems can affect collaboration and, consequently, patient outcomes. In one study, two nurses and one physician conducted a study using nurse and physician focus groups. They identified methods to improve nurse-physician communication (Burke et al., 2004). The researchers noted that some communication problems require major organizational or system changes. However, there are methods that are not system focused but rather individual nurses can use to improve communication and care, for example:

- Develop a personal connection, which helps to increase colleagueship.

- Use humor.

- Recognize that team members are equal in their expertise, which can be important to patient care.

- If you speak frequently to a physician over the phone, arrange to meet in person; a face-to-face interaction may improve your communication over the phone.

- Report good news about patients-improvements, not just problems.

- Recognize that conflict will occur, but this does not mean that communication and collaboration cannot be maintained.

- Discuss preferred methods of communication (telephone, email, pager, in-person, voice message) and under which circumstances they should be used; for example, ask for parameters regarding when the physician wants to be called.

- Identify a plan for future meetings or times of contact so that you are prepared with information and know what you want to communicate. Provide clinically pertinent information.

- Work with the physician to determine the best methods for communicating with the family and determine who should contact whom and for what purposes.

Nurse-physician communication is critical to patient care and to families. Ineffectiveness and inefficiency in communication may be caused by individual personality clashes and sometimes verbal abuse, lack of knowledge about effective communication and issues that impact it, and HCO structure, particularly hierarchical structures that may act as a barrier to communication. Healthcare leaders need to ensure that the work environment supports open communication and appropriate behavior, which requires clear staff expectations and organizational support systems. Another important consideration is an assessment of staff silence when they should be speaking up, for example, about safety and quality. Leaders/managers need to be alert to the level of staff engagement, including team leaders and their teams (Montgomery et al., 2023).

Mindful Communication

Mindful communication is a process in which actively aware individuals engage in communication that is meaningful and timely and respond continually as events unfold (O'Keeffe & Saver, 2014, p. 9; Anthony & Vidal, 2010). This is a method recommended more for individuals but also relevant for teams (Clancy & Webbe, 2022). Mindfulness uses breathing techniques, guided imagery, and other exercises to relax the body and mind and reduce stress. If staff spend too much time problem solving and planning, though these are part of the job, or focus too much on negative thoughts, this can lead to increased stress, anxiety, and even depression and interfere with teamwork. Mindfulness helps staff reengage positively with those around them, improving individual and team performance.

It is easy to assume that one is communicating and participating in an active way by talking, but more needs to be considered about how we communicate, verbally and nonverbally, and why. Then, we need to consider what needs to be communicated and, finally, whether we really did communicate the message we wanted to send. This all requires us to consider the receiver of the message. Many factors affect how our message will be received and even if it will be received as intended. In healthcare settings, these factors are even more complex. Patients are sick, and patient communication may not be at the patient's usual level. The same can be said for families and significant others. Many factors in the work setting, such as stress, miscommunication, power, past problems and current ones, supervisory inadequacies, policies and procedures, understaffing, unprepared staff, workload, and so on, all impact communication-staff to staff, staff to patients and families, and others. The use of mindful, more conscious communication can make a difference in clear communication, sent and received in a timely manner. The same applies to nurse communication in the community. Consider emails-how often do we quickly write an email without thinking about the content or tone and hit the send button only to realize then or later that we could have done better, sent the wrong message, or sent it to the wrong person(s)? This applies to all forms of communication-oral, written, and electronic.

SBAR

Situation-background-assessment-recommendations (SBAR) is a structured communication method that is used to improve team communication (typically, interprofessional, such as a physician-to-nurse but also other types of teams, such as nursing teams). It focuses on critical information about a patient that requires immediate attention and action. To ensure more effective communication and a consistent process, SBAR is used and includes the following steps (IHI, 2023a):

- Situation: What is going on with the patient?

- Background: What is the clinical background or context?

- Assessment: What do I think the problem is?

- Recommendation: What would I do to correct it?

This process includes the use of the call-out and the check-back. The call-out is used to communicate important or critical information, letting all team members hear the information at the same time and clarifying responsibilities. The check-back provides assurance that team members heard and understood the information from the sender. Exhibit 10-1 offers an example of SBAR in action.

| Exhibit 10-1 SBAR Example |

|---|

| This is an example of how SBAR might be used to focus a message in a telephone call between a nurse and a physician. The nurse would not wait for the physician to ask these questions, but rather, when using SBAR, the nurse routinely provides the following information in clear statements. |

| Situation: What is going on with the patient? |

| A nurse finds a patient on the floor. She calls the doctor: “I am the charge nurse on the night shift on 5-West. I am calling about Mrs. Jones. She was found on the floor by her bed and is complaining of pain in her right hip.” |

| Background: What is the clinical background or context? |

| “The patient is a 75-year-old woman who was admitted for pneumonia yesterday. She did not complain of hip pain before she was found on the floor.” |

| Assessment: What do I think the problem is? |

| “I think the fall may have caused an injury. Her pain is level 7 out of 10. Vital signs were taken, and they have not changed since recorded 4 hours ago.” |

| Recommendation: What would I do to correct it or respond to it? |

| “I think we need to get an X-ray and have her seen by the on-call orthopedic resident.” |

Checklists

Dr. Atul Gawande (2014) wrote The Checklist Manifesto to address safety in the surgical arena. His book mandates that all staff working in the surgical arena should use structured checklists. This checklist itemizes a list of activities that should be examined by the team before surgery takes place to ensure clear communication and certainty about actions to be taken. Gawande based his work on the checklist approach used by pilots to ensure safety during takeoff, landing, and other critical points in a flight. We now see checklists used in different areas of health care to ensure processes are followed and to identify potential risks or near misses before they lead to harm and thus improve care. Checklists are not just associated with improving care-reducing errors-but effective use of checklists is also connected to effective team function. A study examined whether perceptions of teamwork predicted the use of the checklist (Singer et al., 2016). In this study, the checklist was used in surgery in only 3% of the surgical cases. When it was used, the team leader, the surgeon, had a significant impact on its use-the leader believed in the use of the checklist and provided clinical leadership, clear communication, and effective teamwork and expected the team would use the checklist.

| Stop and Consider 3 |

|---|

| Improving your communication is an ongoing process. |

In summary, other strategies and interventions that are important in teamwork and communication are (Clancy & Webbe, 2022) structured communication tools, some noted above; empathy training, which helps staff have a better understanding of another person's experience; role model respect, for example, using staff names, showing respect and speaking positively; using effective collaborative bedside rounding with all team members; promoting inclusivity and teamwork, for example, using terms such as “our” patient rather than “your” or “my” patient; providing stress management guidance and services to staff; using team huddles to increase communication and collaboration; offering communication-focused events to provide all staff with a greater understanding of communication; and ensuring access to effective technology with clear policies as to its use.

Healthcare Team Members: Knowledge and Competencies

Team members may be viewed as followers, and this should not be considered a negative term. If there were no members or followers, there would be no team. There may be times when a follower, leader of a subgroup, or another member must assume the leadership role, such as in the absence of the team leader; however, in most cases, team members are followers. The follower role should not be a passive one but rather a very active one. Each member needs to feel a responsibility to participate actively in the team's work and feel that team members have the right to participate in determining team rules, structure, and activities.

Effective teams need members who engage with one another as the team works. This requires the ability to effectively communicate, negotiate, and delegate. Team members need to assess their own dynamics and use time management to get their work done. Sometimes, team members are not on the same site, and in this case, the team needs to determine how they will work together to communicate and coordinate so that outcomes can be met. It is inevitable that teams may experience conflict, either within the team or with persons or teams external to the team. This requires the use of conflict resolution, which is discussed later in this chapter. Effective teamwork takes time and effort, but the results can be much better than individuals functioning alone.

Developing effective interprofessional team education requires the identification of key competencies for all healthcare professions related to teamwork. The following competencies are important. They may look like they form a to-do list, and in a way, it is this type of list because these are the expected actions/competencies of the healthcare team (IPEC, 2016, p. 10):

- Work with other professions.

- Use knowledge of one's own role and roles of other professions to appropriately assess and meet patient healthcare needs; promote population health.

- Communicate with patients, families, communities, and other health professionals, supporting a team approach, maintaining health and the prevention and treatment of disease.

- Apply relationship-building values and team dynamics principles to perform effectively as a team to plan, deliver, and evaluate patient/population-centered care and health; safe, timely, efficient, effective, and equitable.

Accomplishing these competencies requires greater emphasis on interprofessional education for all healthcare profession students as well as ongoing professional education.

| Stop and Consider 4 |

|---|

| Followers are as important to teams as are leaders. |

Teams and Decision-Making

Teams make decisions about activities that they need to do as they work and use problem solving as they make decisions. The amount and quality of information that is required and the number of possible solutions for a problem affect decisions. The schedule is also very important; for example, is an immediate decision required or can time be taken to consider options carefully? Many clinical teams must act quickly in response to clinical problems. These teams need to develop quick thinking and analytic skills (depending on the expertise of team members), trust one another, weigh benefits and risks, and move to a decision. At other times, teams may have more time to fully analyze an issue or problem, brainstorm possible solutions, and develop a consensus regarding the best decision-for example, a decision made by a committee. Teams must recognize that there may not be a perfect solution (there rarely is) and that there is risk, but decisions need to be made. “Not making a decision is really making a decision”-to do nothing is a decision. Several decision-making styles may be used, and the following continue to be relevant styles (Milgram et al., 1999, p. 42):

- Decisive decision-making depends on minimal data to arrive at a single solution or decision.

- The integrative style uses as much data as possible to arrive at several reasonable solutions or decisions.

- The hierarchic style uses a large amount of data and organizes the data to arrive at one optimal decision.

- The flexible style relies on minimal data but generates several different options or will shift focus as the data are interpreted.

The team leader and the team typically use more than one decision-making style, depending on the issue or problem. It is important to understand styles used by team members and the team leader, who is also a team member.

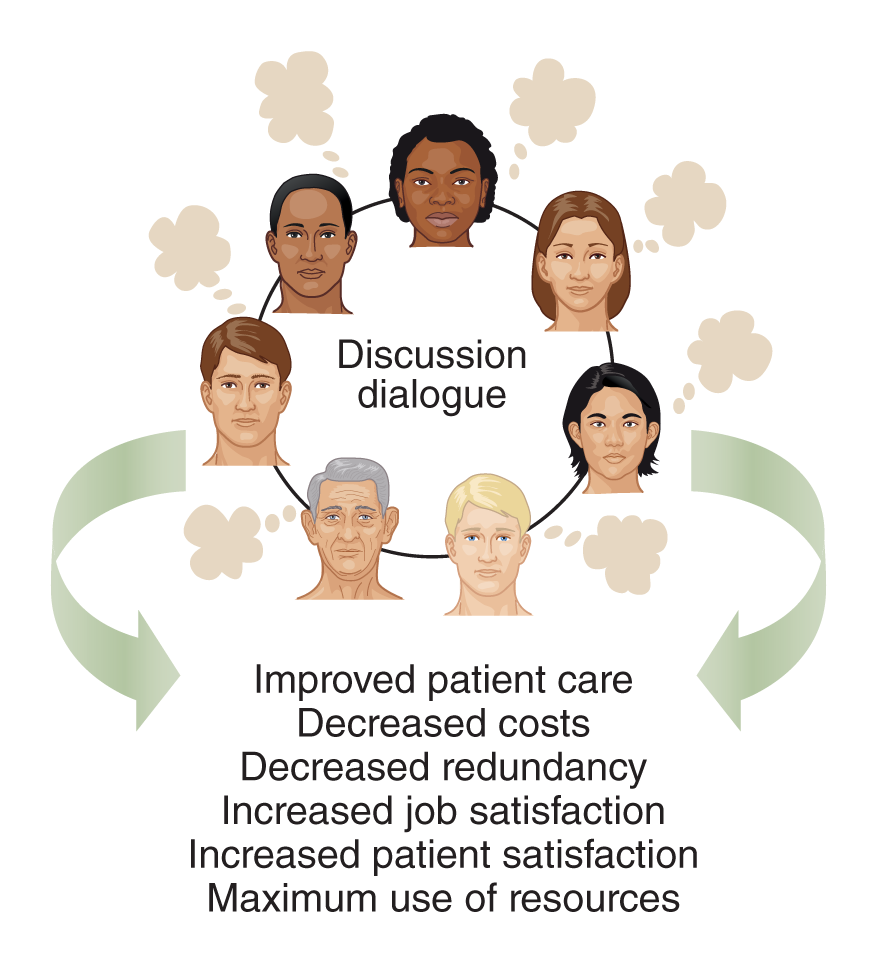

Key questions that are asked during decision-making are: (1) What is the issue, problem, or task to be done and the desired outcome? (2) What type of data is needed? (3) How complicated and substantial is the issue, problem, or task? (4) Who are the key stakeholders to consider? (5) How many possible solutions or approaches are there, and what are they? (6) Can the desired outcome(s) be met with acceptable cost-benefit standards? (Note that cost is more than financial. It could refer to the patient's health status if an outcome is not achieved, or there is a risk of an error due to a decision-making problem, and so on.) Figure 10-6 illustrates team thinking. Exhibit 10-2 provides an example of a team-thinking inventory that teams can use to assess their thinking.

| Exhibit 10-2 Team-Thinking Inventory |

|---|

|

Figure 10-6 Interprofessional team thinking.

An illustration depicts a circle of seven diverse individuals engaged in discussion dialogue.

Arrows around the circle lead to the benefits listed: improved patient care, decreased costs, decreased redundancy, increased job satisfaction, increased patient satisfaction, and maximum use of resources.

Rubenfeld, M. & Scheffer, B. (2015). Critical thinking tactics for nurses. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

| Stop and Consider 5 |

|---|

| Team decision-making never stops. |

Collaboration

Collaboration is an integral part of PCC and safe, quality care. When staff or team members work in a collaborative environment, it is a more satisfying work experience with limited conflict. Collaboration means that all the people involved are listened to and decisions are developed together. Views are respected; however, at some point, decisions must be made, and not all views or opinions will be part of the final decision. Compromise is part of effective collaboration. The goal is to arrive at the best possible decision. Working with others increases the possibility of making the best decision because there is a greater availability of ideas and dialogue about ideas and solutions. Though diversity may cause barriers, it can also improve decision-making by providing different viewpoints to better understand an issue.

The American Nurses Association (ANA, 2021) nursing standards include a standard on collaboration, recognizing its importance to professional nursing practice and supporting PCC. It requires nurses to communicate, collaborate with the plan of care, promote conflict management, build consensus, engage in teamwork, cooperate, and partner with others to effect change and produce positive outcomes while adhering to professional standards and codes of conduct. Effective collaboration identifies potential stakeholders or partners and their expertise, level of power and influence, and common goals.

A systematic review of nurse-physician collaboration examined studies to describe nurses' and physicians' perceptions of their collaboration and the factors that influenced these perceptions (House & Havens, 2017). There were different views of collaborative effectiveness, and the review includes frequent comments about shared decision-making, teamwork, and communication. The review indicated a need for more interprofessional education for nursing and medical students to develop a clear definition and understanding of collaboration and how it should be applied by these students and then as healthcare professionals.

Other factors that influence collaboration that are not always considered are space and the work environment (Gum et al., 2012). What does this mean? In most clinical units, there is a space that is central for staff to use as they plan and coordinate work. In hospitals, this space has often been called the nurses' station; however, this title may act as a barrier to improving interprofessional collaboration. The title for the space should not focus on one profession, and this is changing so that it is more inclusive. Teams need space in which they can collaborate, discuss issues and patients, plan, and so on. This then means the space needs to provide privacy and quiet with limited interruptions. The unit workstation, as described here, does not usually meet these criteria-it is noisy, offers little privacy, and is often crowded and stressful. Nurses and others need to consider the space in which they work and collaborate and make changes to improve workspaces, which will then improve work outcomes.

Collaboration requires open communication with team members feeling comfortable expressing their opinions even when they disagree. Team members from different healthcare professions must work across professional boundaries to develop a team culture of working together. The goal is not to make an individual's profession look good but rather to focus on the team as a whole and its purpose. Even when the team is composed of members from the same healthcare profession, such as a nursing team, the focus is on the team not on individual team members. This does not mean that conflicts will not occur, but some conflicts can be prevented. When conflict does occur, the team needs to use effective methods for coping to reach a common goal of reduced conflict, which means reduced stress.

| Stop and Consider 6 |

|---|

| Healthcare delivery requires more and more collaboration. |

In summary, as was demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, teams were important but also experienced problems. An observational study of 50,000 healthcare workers (HCWs) in three large medical centers examined staff culture, including teamwork climate, safety climate, leadership engagement, improvement readiness, emotional exhaustion, emotional exhaustion climate, thriving, recovery, and work-life balance (Kyle et al., 2022). The study concluded that teamwork deteriorated during this time. The researchers noted that “speaking up, resolving conflicts, and interdisciplinary coordination of care were especially predictive. Facilities sustaining these behaviors were able to maintain other workplace norms and workforce well-being metrics despite a global health crisis. Proactive team training may provide substantial benefit to team performance and HCW well-being during stressful times” (Kyle et al., 2022, p. 40). This type of information needs to be applied and used routinely and during emergencies to develop and improve teams and collaboration.

Coordination

Nurses coordinate patient care through planning and implementing care, and they have been involved in the development of care coordination throughout its evolution (Lamb, 2013). “Care coordination involves deliberately organizing patient care activities and sharing information among all the participants concerned with a patient's care to achieve safer and more effective care. This means that the patient's needs and preferences are known ahead of time and communicated at the right time to the right people and that this information is used to provide safe, appropriate, and effective care to the patient” (HHS, AHRQ, 2019). Effective coordination needs to be interprofessional. Coordination and collaboration should be interconnected, and both are included in the ANA standards (2021). Care is complex, and patients require healthcare providers with different expertise to meet these needs. With this type of situation, different providers need to collaborate to develop a plan and then implement and coordinate care in a manner that makes sense-meeting the timeline required, with minimal conflict and confusion.

Although the need for care coordination is clear, there are obstacles within the U.S. healthcare system that must be overcome to provide this type of care. Redesigning a healthcare system to better coordinate patient care is important for the following reasons (HHS, AHRQ, 2019):

- Current healthcare systems are often disjointed, and processes vary among and between primary care sites and specialty sites.

- Patients are often unclear about why they are being referred from primary care to a specialist, how to make appointments, and what to do after seeing a specialist.

- Specialists do not consistently receive clear reasons for the referral or adequate information on tests that have already been done. Primary care physicians do not often receive information about what happened in a referral visit.

- Referral staff deals with many different processes and lost information, which means that care is less efficient.

Coordination through team effort-working to see that the pieces and activities fit together and flow as they should-can help to meet patient outcomes (HHS, AHRQ, 2018). “Conscious patient-centered coordination of care not only improves the patient experience, it also leads to better long-term health outcomes, as demonstrated by fewer unnecessary trips to the hospital, fewer repeated tests, fewer conflicting prescriptions, and clearer advice about the best course of treatment” (HHS, 2013).

Patients often complain about the number of care providers that interact with them. They may not know who is responsible for which aspects of their care, and they may receive confusing and conflicting information. The patient needs to have an anchor-a healthcare provider to whom the patient can turn for support and knowledge of the plan. Basically, patients are saying that they are not the center of care, and their care is fragmented. This leads to an increased risk of errors and decreases the quality of care. Care is coordinated through the implementation of the care plan, documentation of care, and teamwork. Healthcare teams that recognize these concerns can help patients more, engaging patients in the care as a member of the care team. This increases opportunities to improve care and reach outcomes.

Barriers and Competencies Related to Coordination

Coordination is not easy to achieve even when team members want to achieve it. Some of the barriers to effective coordination are listed here:

- Failure of team members to understand the roles and responsibilities of other team members, particularly members from different healthcare professions

- Lack of a clear interprofessional plan of care

- Limited leadership

- Overwork and excessive burden of team member responsibilities

- Ineffective communication, both oral and written

- Lack of inclusion of the patient and family/significant others in the care process

- Competition among team members to control decisions

Despite these barriers, coordination can be achieved by using effective interventions. First, the team must recognize that coordination is critical and strive to ensure that it is used. The team needs to understand the purpose and goals of coordination and work to achieve them. To do so, the team must evaluate its work and be willing to identify weaknesses and figure out methods to improve coordination. Team members need to communicate openly and in a timely manner. Teams that effectively solve problems together will improve their coordination. Delegation, discussed elsewhere in this chapter, is an important part of coordination. One person cannot do everything (and that one person may not even be the best person for the task or activity). Coordination requires team members who understand the different roles and expertise of the members, determine the best member to deliver care to meet the timeline, and then evaluate the outcomes.

Tools to Improve Coordination

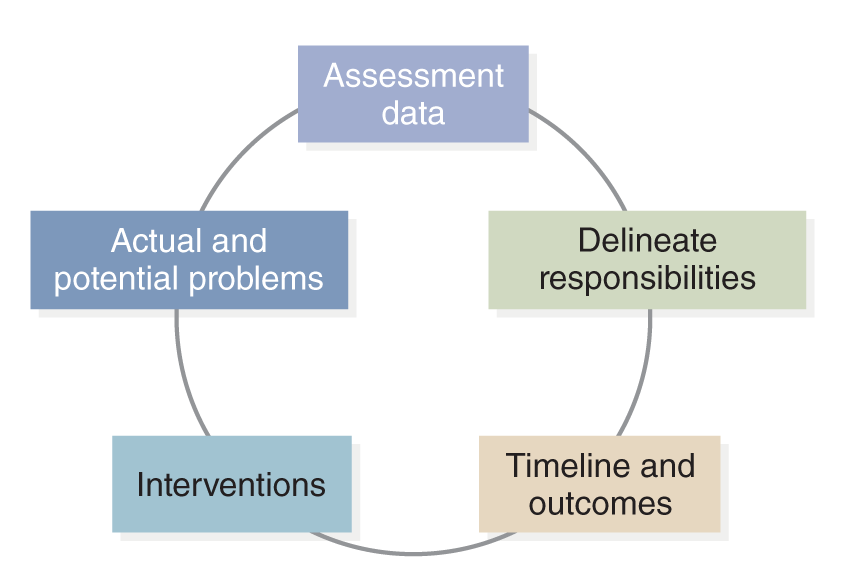

Health care has developed a variety of tools and methods to increase coordination. From a chronic illness perspective, disease management is a process used to improve coordination and collaboration, typically uses practice guidelines and clinical protocols or pathways. A clinical protocol or pathway is a written guide providing direction for specific clinical problems. The pathway content includes interventions, timelines, and resources needed; identifies expected outcomes; and provides a sequencing of interventions to reach the outcomes. Figure 10-7 provides examples of information categories that might be found in a clinical pathway.

Figure 10-7 Categories of information found in clinical pathways.

An illustration depicts the types of information in clinical pathways, arranged in a circular flow. The categories include assessment data, actual and potential problems, interventions, delineate responsibilities, and timeline and outcomes.