This chapter acts as a practical summary guide to deprescribing benzodiazepines and z-drugs.

Determine whether to perform a direct taper from the benzodiazepine or z-drug being used or to switch to a longer-acting benzodiazepine. Research evidence is equivocal about which approach is best and patient preference should be considered. 1, 14, 20, 26 In the drug-specific tapers given in the rest of this chapter both options are provided.

- Patients who may benefit most from a switch before tapering are those suffering from inter-dose withdrawal, or who are taking medication for which small doses are not easily available.

- Patients who have had trouble with switching in the past or prefer to proceed with a familiar drug should be supported to do so. 34, 35, 36

- There is consensus that a patient-directed taper, adjusted to symptoms is the most successful approach to cessation. 27 The key elements of a programme of tapering are:

- that it is flexible and can be adjusted so that the process is tolerable for the patient,

- that it involves close monitoring of withdrawal symptoms to facilitate timely adjustments to the rate of taper, and

- that patients are provided with preparations of medication to make the process of creating doses that cannot be made with available tablet doses (e.g. liquid formulations or smaller dose formulations of tablets)

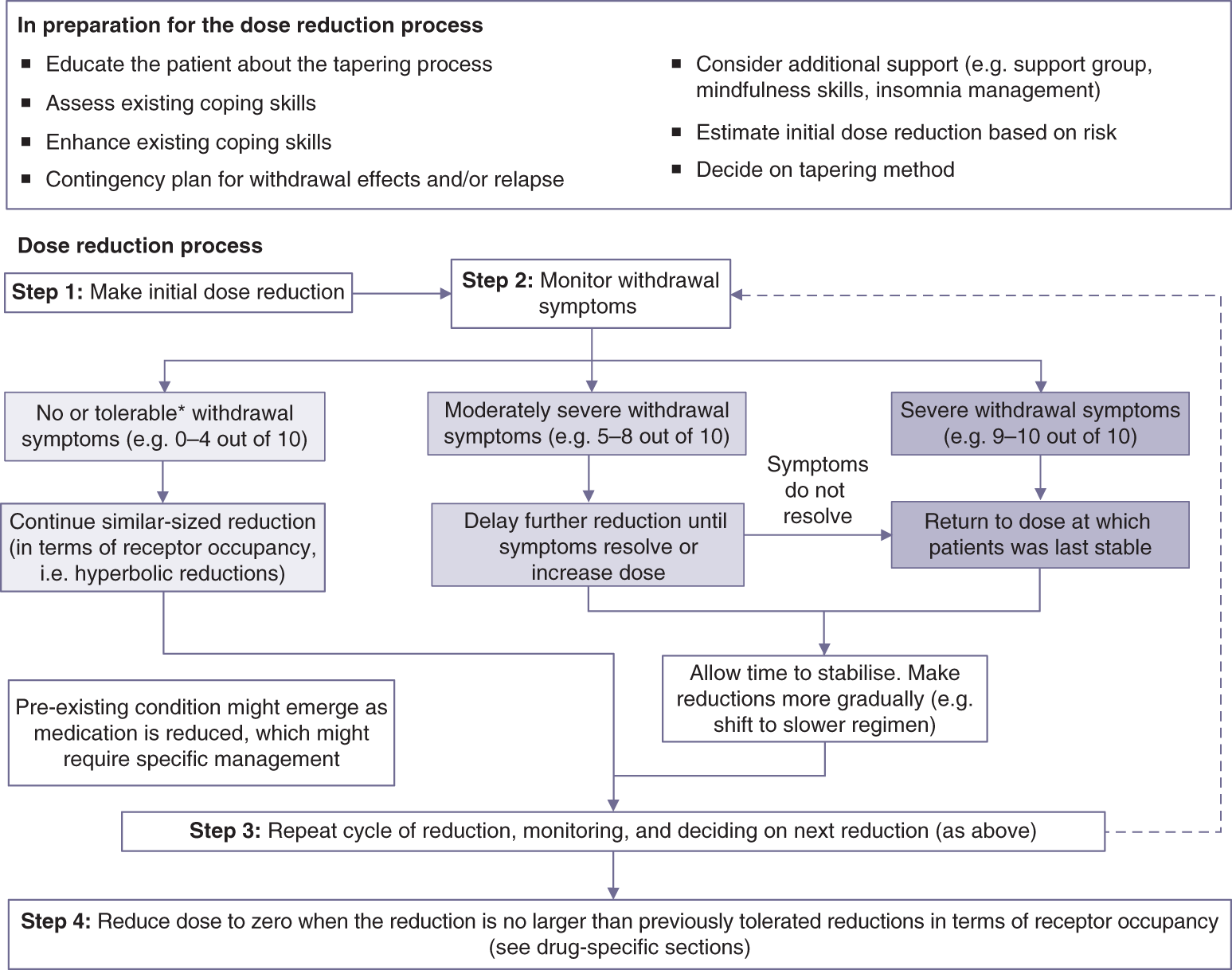

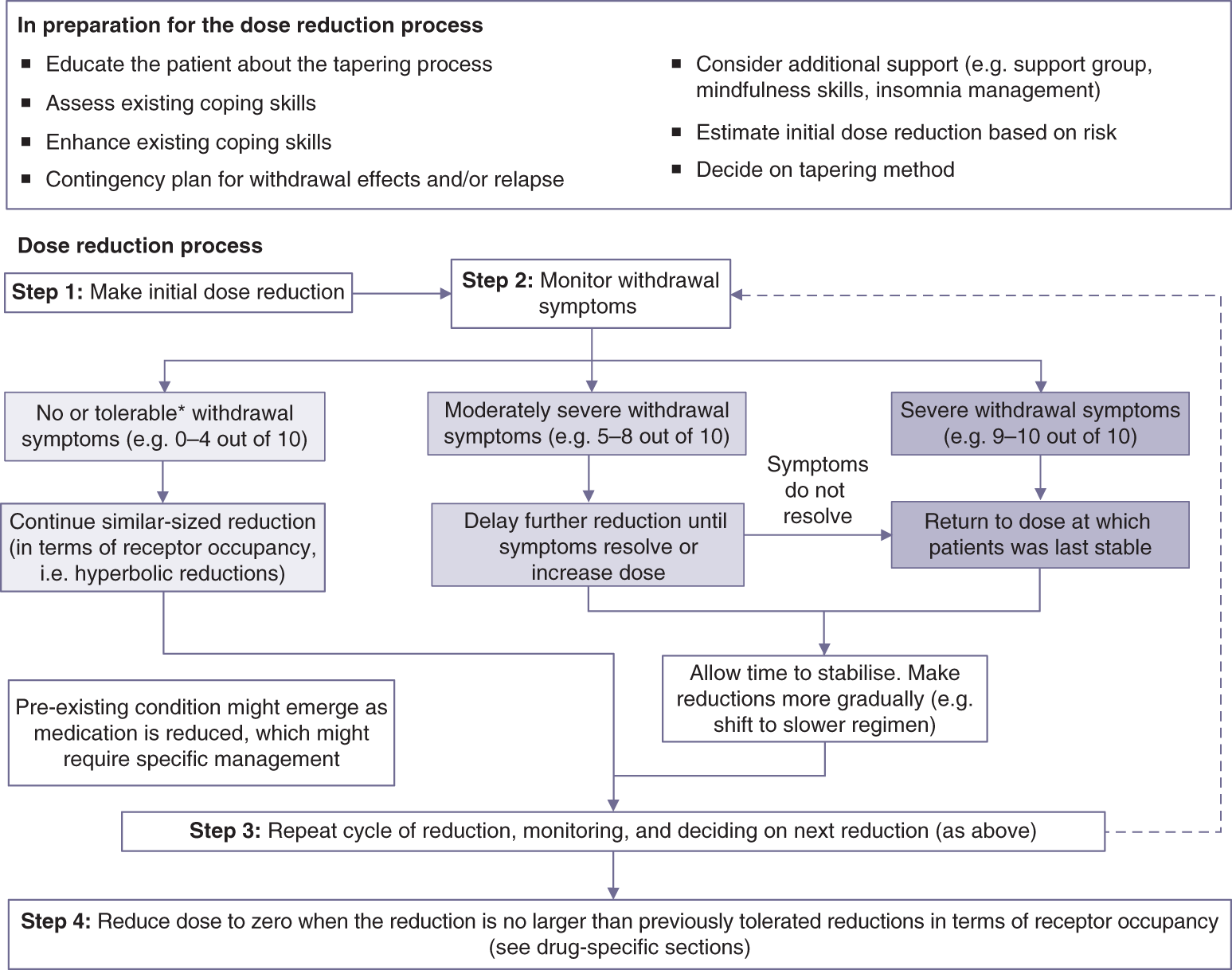

The process of tapering involves the following four steps (Figure 3.5 ).

Figure 3.5 An Overview of the Process of Tapering Benzodiazepines and Z-Drugs. *what Constitutes Tolerable Withdrawal Symptoms Will Vary from Person to Person.

Patients may be broadly risk stratified according to what is known about risk of withdrawal in a suggested approach below. It is better to err on the side of caution when estimating the risk category, and so the presence of any moderate- or high-risk characteristic should assign a patient to that category. Tapers can always be increased in speed if no difficulties are encountered - but the reverse can be more problematic.

Low-risk patients could start with approximately 20% (or less) dose reductions (e.g. the faster regimens given in the drug-specific sections). This group is characterised by:

- no evidence of tolerance to the medication,

- no evidence of inter-dose withdrawal,

- short-term use ( weeks),

- taking longer half-life benzodiazepines,

- no or mild withdrawal symptoms in the past on stopping or skipping a dose, and

- no or limited history of benzodiazepine (or other psychiatric medication) use and cessation. 34, 35, 36

Note that some patients who have only used benzodiazepines short term can also experience withdrawal effects, 34, 35, 36 but this is rarer than in long-term use.

Moderate-risk patients could start with approximately 10% (or less) dose reduction (e.g. the moderate regimens given in the drug-specific sections). This group is characterised by:

- some evidence of tolerance to the medication,

- some experience of inter-dose withdrawal,

- moderate-length use (months),

- moderate withdrawal symptoms in the past on stopping or skipping a dose, and

- some history of benzodiazepine (or other psychiatric medication) use and cessation. 14, 20

High-risk patients could start with 5% (or less) dose reduction (e.g. the slower regimens given in the drug-specific sections). This group is characterised by:

- evidence of significant tolerance to the medication,

- marked experience of inter-dose withdrawal,

- past history of severe withdrawal symptoms on dose reduction or skipping doses,

- taking shorter half-life benzodiazepines,

- older or otherwise physically frail, and

- repeated cycles of benzodiazepine (or other psychiatric medication) use and cessation (which is thought to lead to sensitisation, a phenomenon sometimes called kindling). 14

- In order to instil confidence in patients in what can be a daunting process, it may be advisable to start with an even smaller dose reduction in order to alleviate patients' fears about the process.

- None of the suggested regimens should be imposed on the patient but are a starting point to assess how the patient tolerates the process.

- If a patient prefers to try a smaller dose reduction than their risk category suggests this should be supported.

- People taking z-drugs once at night will tend to fall into the lower-risk category because z-drugs are likely to produce less physical dependence than benzodiazepines as they are probably largely eliminated in each 24 hour period. 37

- The most important information to determine the rate of reduction is how the patient experiences the process. Imposed regimens tend to backfire. 37, 38 Withdrawal symptoms should be monitored for 1-4 weeks or as long as it takes for symptoms to start to ease.

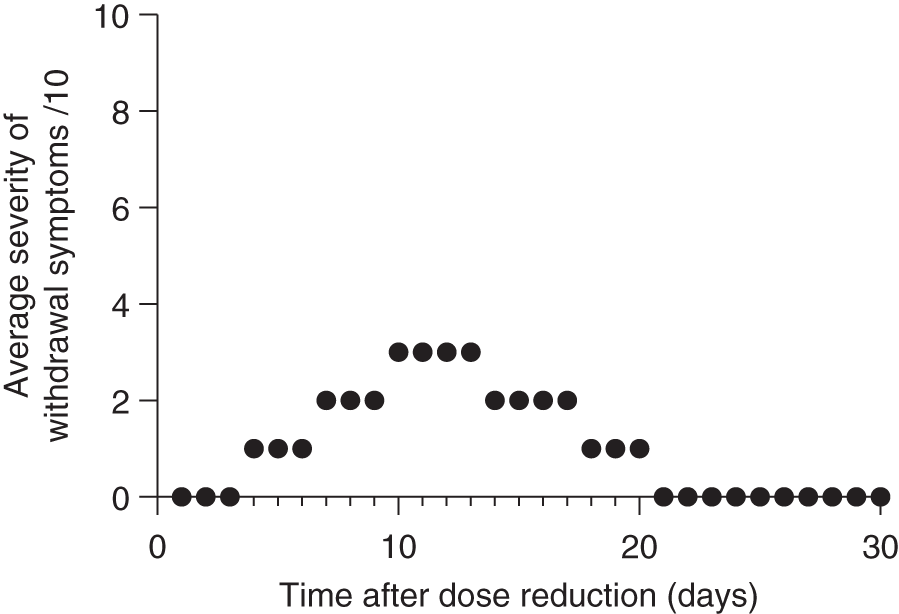

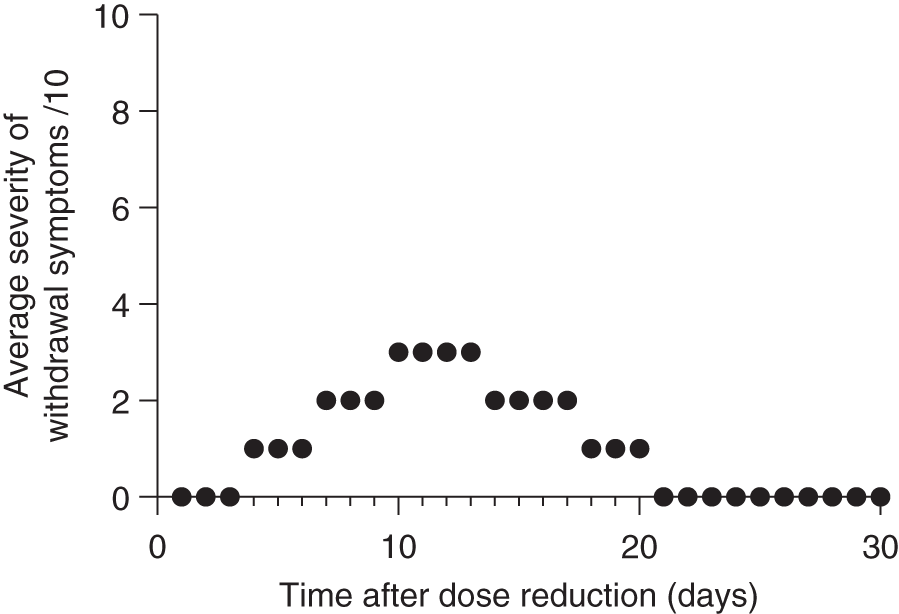

- Although there are various formal scales used to measure withdrawal symptoms, these can be cumbersome because of the number of items, and potentially miss the importance of one or two significant symptoms. 39 An alternative is to rate a small number of core withdrawal symptoms such as anxiety, insomnia or other prominent symptoms out of 10 (0 = no symptoms, 10 = extreme symptoms) or to rate withdrawal symptoms out of 10 overall. This monitoring often detects a 'wave' pattern of withdrawal symptoms: where symptoms increase, reach a peak, start to resolve and return to or approach baseline (Figure 3.6 ).

Figure 3.6 Graphical Representation of Withdrawal Symptoms Following a Dose Reduction of a Benzodiazepine. These Probably Constitute Mild to Moderate Symptoms. The Y-Axis Shows the Average Patient-Rated Severity of Withdrawal Symptoms. Note the Delayed Onset of Significant Symptoms after Drug Reduction, Probably Related to Drug Elimination, Followed by a Peak and Then Easing of Symptoms, Probably Related to Re-Adaptation of the System to a New Homeostatic 'set-Point' (Similarly to Figure(s) 3.4b and C).

The information from monitoring can be used to determine the frequency and size of reductions (Figure 3.7). See further examples in 'Tapering antidepressants in practice' but briefly:

- if symptoms take 2 weeks to resolve and the severity is mild (e.g. less than 4 out 10) then similar-sized reductions (in terms of receptor occupancy) could be made every 1-4 weeks so that subsequent symptoms do not accumulate;

- if symptoms take longer to resolve or their severity is moderate (e.g. 5 to 8 out of 10) then further time between reductions will be required and/or smaller reductions made in future;

- if symptoms are severe (e.g. 9 or 10 out 10) then dose should be increased to the last dose at which the patient was stable, wait for stabilisation and then make reductions at half the rate, or less.

It is important that these decisions are reached jointly and that a too fast rate of taper is not imposed on patients.

Patients can taper in steps ('cut and hold', e.g. at intervals of 1-4 weeks) as outlined above or, alternatively, they can taper in smaller amounts (e.g. every day), often called micro-tapering. There are pros and cons to each approach:

- Tapering in steps is simpler and can often be performed with existing tablet formulations of some medications (e.g. halving and quartering 2mg diazepam tablets). Larger, less frequent reductions can cause greater symptoms (see Figure 3.4).

- Micro-tapering involves more complicated calculations and use of formulations other than tablets (e.g. manufacturers' liquids or suspensions of tablets). It can reduce the severity of symptoms making the process of tapering more tolerable by 'spreading' out changes to established equilibria. 40 See the drug-specific section for example regimens (e.g. by reducing by 0.05mg per day from 20mg of diazepam).

A variety of different formulations can be used for tapering:

- Commercially available tablets: small doses are preferable, with round tablets able to be divided into halves and quarters using a tablet cutter (more accurate than breaking along a score line). 41

- Manufacturers' liquids: using a syringe for precise measurement. Further dilution in water is sometimes required for small doses.

- Compounded tablets or liquids: specialist pharmacies can prepare lower-dose tablet formulations or liquid suspensions. One example is 'tapering strips'. 42

- Suspending tablets or capsules: tablets can be crushed and dispersed in water or milk. Capsules can be emptied to disperse in water or milk. Suspension of tablets is an off-label but widely recommended method by authoritative pharmaceutical guidance 43, 44, 45 and is commonly used by patients. 20, 46

After tapering

Some patients can have ongoing withdrawal symptoms following cessation. Sometimes this lasts just for several days or weeks but occasionally is extended for months or sometimes years, termed protracted withdrawal syndrome. 47, 48 See the subsequent section 'Management of complications of benzodiazepine and z-drug discontinuation' for further details.

Other considerations

- Extending the dosing interval ('skipping doses') to taper is ill-advised as it can lead to inter-dose withdrawal symptoms, unless involving benzodiazepines with very long half-lives such as diazepam. It is preferable to give smaller doses each day using one of the techniques outlined previously.

- Withdrawal symptoms are best managed by adjustment of the taper rate, rather than 'white-knuckling' through the process. It is thought that severe withdrawal effects may make a protracted withdrawal syndrome more likely. 26

Adjunctive medication has mixed evidence, with authoritative guidance recommending against its use 51, 52 and it should be reserved for very severe cases. 53, 54

- Short-term use of propanolol, 20, 28 and perhaps antihistamines might be warranted in severe withdrawal. Carbamazepine might be reserved for extremely difficult cases.

People can become sensitised to various medications during the process of withdrawal for reasons that are not well understood. 20

- The most noteworthy of these include alcohol and antibiotics (especially fluoroquinolones which can displace benzodiazepines from the GABA receptor). 55

- There are reports of sensitivities to steroids, other medications, caffeine, nicotine, supplements and even specific foods. 20, 28

- The use of some of these medications may be unavoidable, but greater caution than usual should be exercised with any supplement or medication. 20

Potential pitfalls

- Physiological dependence can develop in a matter of days so some people will have withdrawal symptoms after just short-term use.

- Physiological dependence and the experience of withdrawal effects does not indicate addiction. Addiction centres are therefore not advised for people suffering withdrawal effects from benzodiazepines without abuse or misuse - sometimes treatment at these centres involves abrupt cessation with other medications added in to 'cover' withdrawal effects, or inappropriate 12-step approaches irrelevant to medication taken as prescribed.

- Some symptoms can seem bizarre but should not be discounted as many of these are recognised withdrawal symptoms (see section on withdrawal effects) (e.g., depersonalization/derealization, agoraphobia, intrusive thoughts, burning nerve pain, irritable bowel). 49, 56

- Symptoms of benzodiazepine withdrawal can mimic other conditions, leading to misdiagnosis (e.g. functional neurological disorder, medically unexplained symptoms, psychosomatic conditions, chronic fatigue syndrome, anxiety disorder, depression, bipolar disorder, neurological disorders) and unnecessary testing and medical treatment. 56, 57

- The drug-specific taper protocols in the following sections are meant to be a guide only: flexibility is key. The patient's experience of withdrawal symptoms should be the main guide to the rate of taper.

- Post-withdrawal recovery may take 12-18 months, and sometimes longer.