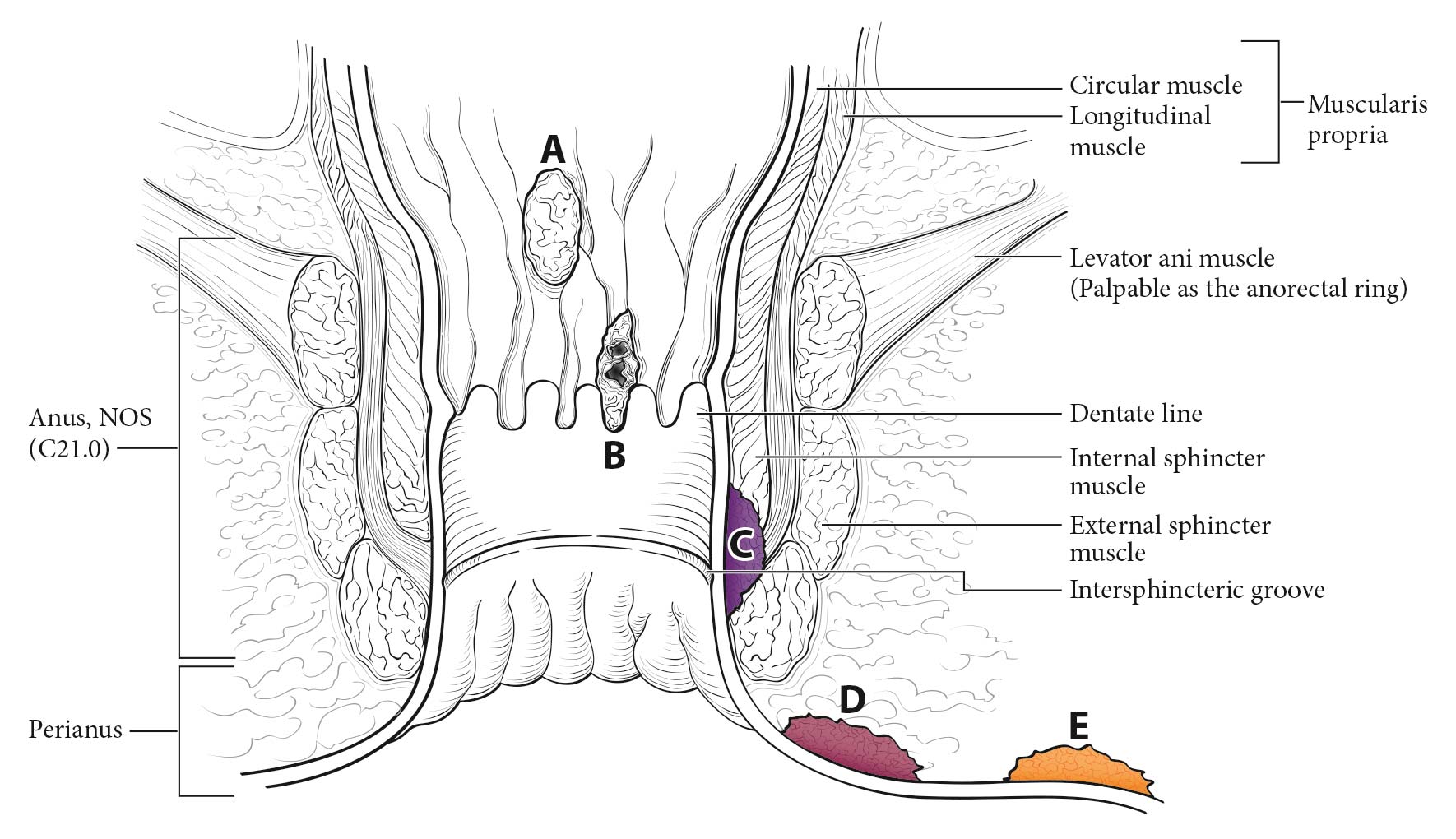

This classification applies to carcinomas of the anal canal and perianus (formerly anal margin). The land marks that define the anal canal and perianus are discussed and illustrated in the anatomy section. This chapter also covers the pathological classification and staging of carcinomas of the perianal region.

Anal cancer is rare, representing only 0.4% of all new cancer cases in the United States. The incidence is higher in women than men, 2.0 versus 1.5 per 100,000, respectively, with an overall rate of 1.8 per 100,000 persons. The incidence of anal cancer in both men and women has been rising steadily in the United States over the past decade, increasing roughly 2.2% each year.1 In 2014 alone, 7,210 new anal cancer cases were estimated in the United States, with 950 deaths.1,2 In comparison, only approximately 27,000 cases of anal cancer were diagnosed worldwide in 2008.

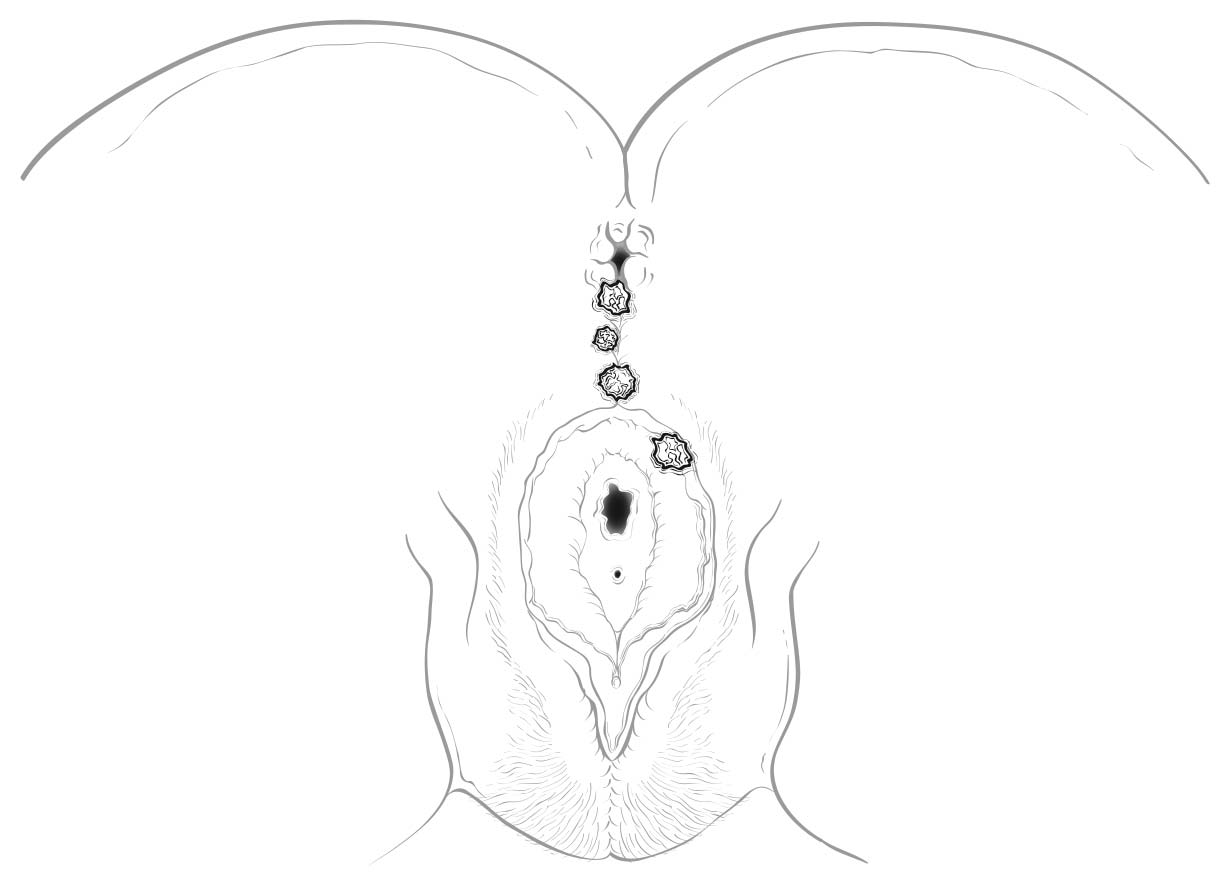

A focus of this chapter is to further refine the TNM staging system to clarify what constitutes anal canal versus perianal cancer and to specify additional considerations that may be of value for cancers in the region of the perianus and vulva. For instance, squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) overlying the perineal body may be classified as perianal or vulvar, and the treatment plans may be quite dissimilar. For this reason, we recommend the following: lesions that clearly arise from the vulva and extend onto the perineum and potentially involve the anus should be classified as vulvar. Similarly, lesions that clearly arise from the distal anal mucosa and extend onto the perineum should be classified as perianal. Lesions localized to the perineum that are not clearly arising from either the vulva or the anus should be categorized based on the clinician's clinical impression. Thus, we recommend the following terminology: perineum favor vulva and perineum favor perianus. We also recommend consulting with colleagues in gynecologic oncology, colorectal or general surgery, or surgical oncology, because classification has a significant impact on treatment.

Most carcinomas of the anal canal and perianal region are SCCs. The terms transitional cell and cloacogenic carcinoma have been aband oned, because these tumors are now recognized as nonkeratinizing types of SCC.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

The predominant histologic type of malignancy arising in the anal canal is SCC. Estimates suggest that 95% of these cancers are caused by oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) types, with HPV 16 associated with 89% of cases.3-6 Higher-risk populations are men who have sex with men and people who are immunosuppressed. Mortality rates are rising as well, with an average increase of 1.7% each year from 2001 to 2010. Only 65.5% of patients survive 5 years or more.1 Nonsquamous anal cancers include adenocarcinomas, basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), and melanomas (not discussed here).

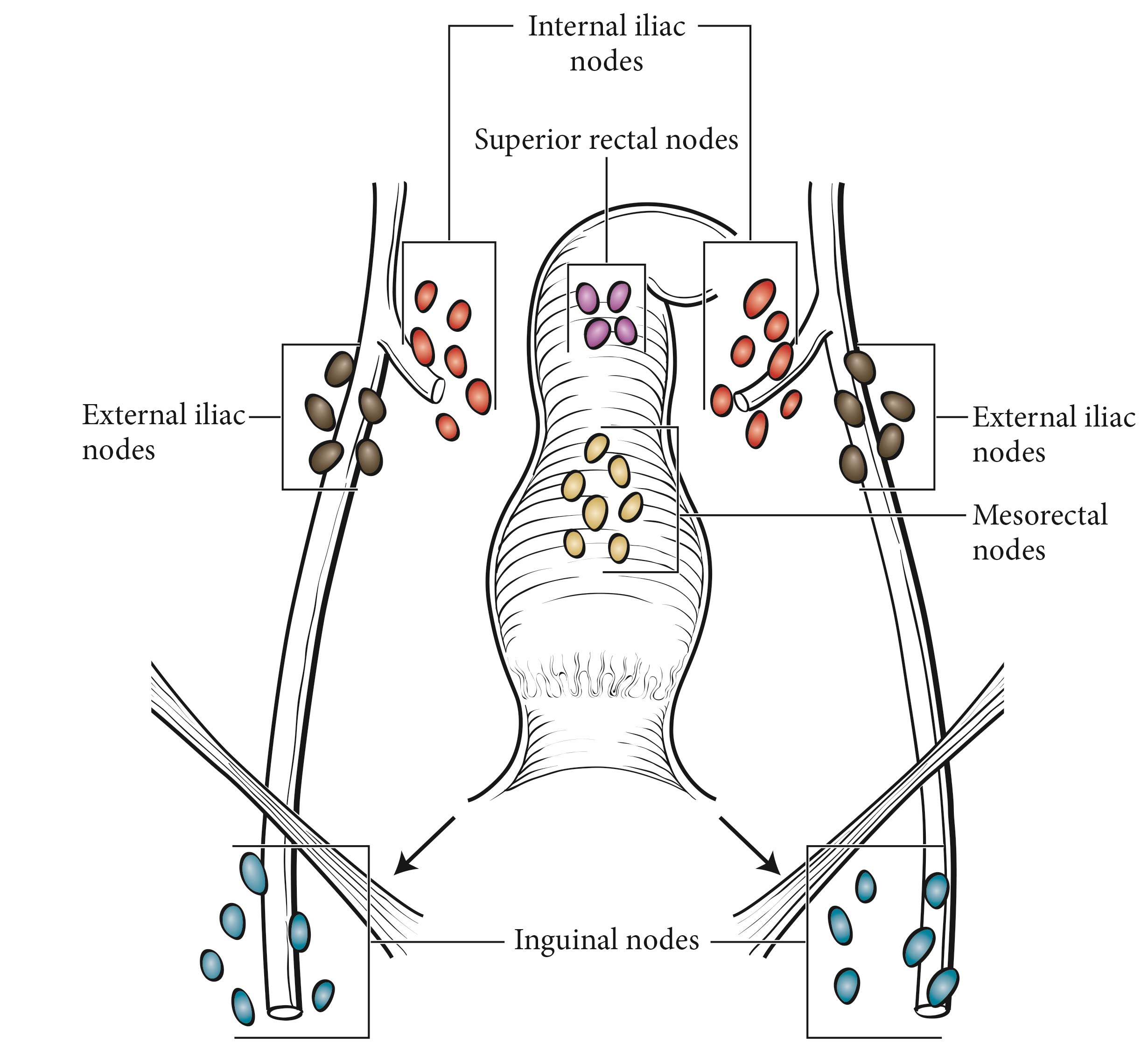

Carcinomas of the anal canal typically are staged clinically according to the size and extent of the untreated primary tumor. Patients with cancer of the anal canal typically are staged at the time of presentation with inspection, palpation, and biopsy of the mass; palpation (and biopsy as needed) of regional lymph nodes; and radiologic imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) is not a malignancy and should not be coded as such. Direct evidence supports the progression of HSIL to SCC, but the impact of treatment on the progression to carcinoma is being studied in the ANCHOR trial, a multi-institutional rand omized prospective trial comparing observation with excision/destruction.7

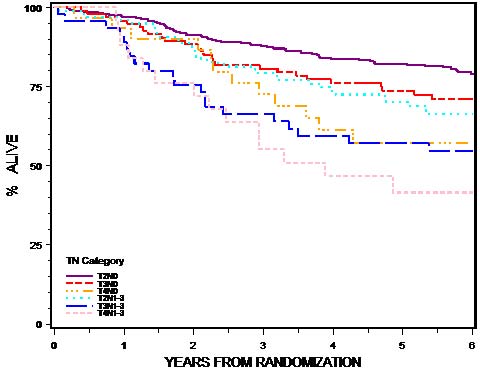

The primary management of SCCs of the anal canal is nonoperative, involving combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Fortunately, localized SCC of the anal canal has been associated with excellent outcomes with combined-modality therapy, with a 5-year overall survival rate of 78% in the positive arm of a US phase III rand omized trial, Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 98-11.8

In contrast, the management of perianal carcinomas remains mixed, with both operative and nonoperative treatments used selectively, based on involvement of adjacent structures, tumor size, and histology of the primary lesion. Complete pathological staging is possible for a perianal primary tumor treated surgically. The remainder of the staging of regional lymph nodes and distant disease in perianal tumors is as described for anal cancers.

Other Histologic Types

Verrucous Carcinoma

Verrucous carcinoma historically has been distinguished from ordinary condyloma acuminatum by its apparent combination of exophytic and endophytic growth.9-11 However, the appearance of endophytic growth may, in fact, represent growth along preexisting cryptogland ular fistulous disease rather than actual endophytic invasion, as convincing evidence of actual invasion is rare. Some verrucous carcinomas contain HPV, the most common types being HPV 6 and HPV 11. This is another distinction from SCCs, which demonstrate predominantly HPV 16. Treatment typically focuses on local control in the absence of invasion. However, any histologic evidence of invasive disease or metastasis should lead to the diagnosis of SCC and appropriate therapy.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

BCC of the perianus is an uncommon entity, with a reported incidence of about 0.1% of all BCCs and less than 1% of all anorectal neoplasms.12-14 Differentiating basaloid SCC from BCC may be challenging, as they have similar histologic features. However, SCCs arise from a known precursor lesion (anal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia), whereas BCCs do not have a well-defined precursor. SCCs may be distinguished further from BCCs in that they may arise from the anal mucosa or the perianal skin, whereas BCCs usually arise in the perianal skin. Rarely, BCCs may extend from the perianal skin into the anal canal. In general, BCCs are associated with a low recurrence rate (0-29%), and wide local excision with negative margins remains the stand ard of care, especially for smaller lesions. Electrodesiccation and curettage, Mohs micrographic surgery, and external beam irradiation also have been reported with successful results.15 Radiation and /or abdominal-perineal resection may be required for large lesions and recurrent tumors.

Adenocarcinoma

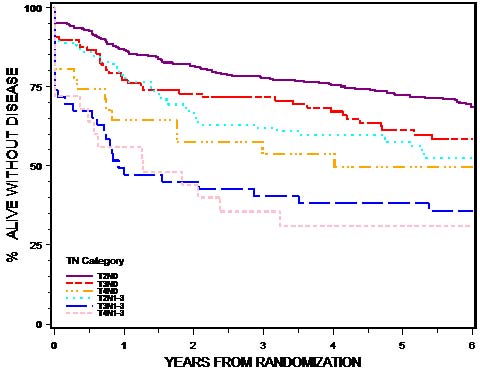

Adenocarcinomas of the anus and perianus are rare and generally fall into three categories: those that extend down from above the dentate line, those that originate from the underlying anorectal gland s or longstand ing fistulous disease, and those arising primarily from the anal mucosa or perianal skin.16-18 Lesions in the perianal skin may be amenable to wide local excision in select cases. Most perianal, anal, and distal rectal lesions extending into the anal mucosa are treated with abdominal perineal excision with or without neoadjuvant chemoradiation. The outcomes for all other histologic types, including adenocarcinomas, are poorer, stage for stage, than for SCC (Table 21.1).

The presumed precursor lesion for perianal adenocarcinoma, extramammary Paget disease, is adenocarcinoma in situ. Anal Paget disease may be divided into two classes. About half the cases are associated with synchronous or metachronous colorectal malignancies; the other subset does not appear to be associated with internal malignancies but is associated with a high local recurrence rate and is more likely to progress to invasive cancer.19 Perianal Paget disease may be treated with wide local excision.20,21