A.6. What is a thoracic aortic dissection? How does it typically present? How is it diagnosed?

Answer:

AAS can present as an aortic dissection, IMH, and penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer (PAU). The most common AAS is aortic dissection. An aortic dissection occurs when a tear in the aortic intima allows blood to enter the aortic media, which creates a dissection flap that separates the true from the false lumen. The dissection flap can have anterograde or retrograde propagation, resulting in life-threatening complications, such as acute aortic regurgitation (AR), myocardial ischemia, cardiac tamponade with possible cardiogenic shock, acute stroke, or malperfusion syndromes (Figures 9.6 and 9.7). Blood in the false lumen can create a reentry tear back through the intima into the true lumen, or it can tear through the outer media and adventitia, resulting in aortic rupture. The relative risk of aortic dissection increases dramatically at a diameter greater than or equal to 4.5 cm. When blood infiltrates the aortic media, an IMH forms when the outer wall of the aorta is pushed outward or a PAU forms when blood is confined by the atherosclerotic scarring of the aorta, resulting in a localized dissection or pseudoaneurysm. Up to 47% of IMH can progress to aortic dissection while PAUs have up to a 40% risk of rupture.

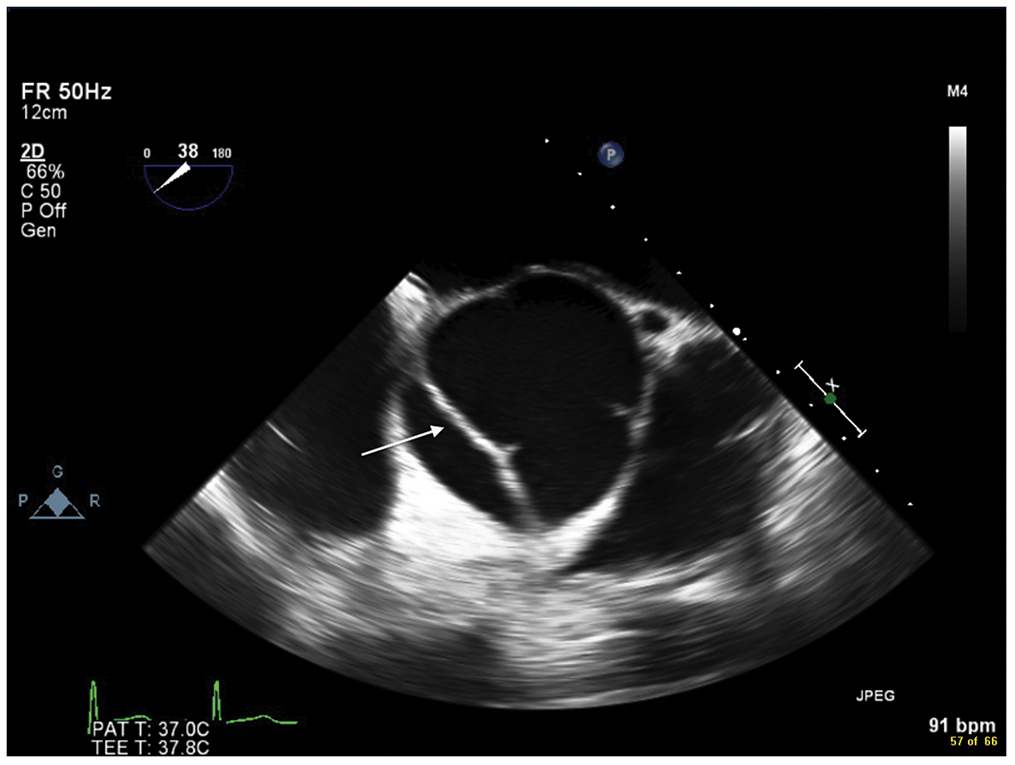

Figure 9.6.: Midesophageal Aortic Valve Short-Axis View on Transesophageal Echocardiography Demonstrating an Acute Aortic Dissection (Arrow) that Extends Proximally to the Aortic Valve in a Young Patient with Marfan Syndrome.

Midesophageal aortic valve short-axis view on transesophageal echocardiography demonstrating an acute aortic dissection (arrow) that extends proximally to the aortic valve in a young patient with Marfan syndrome.

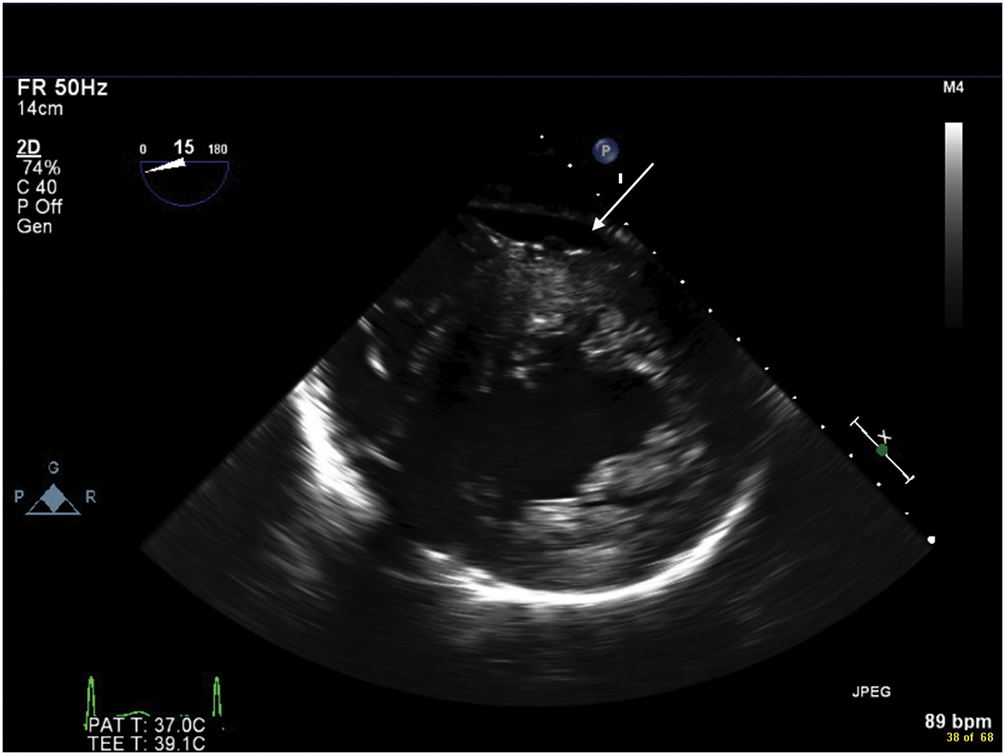

Figure 9.7.: Transgastric Midpapillary View on Transesophageal Echocardiography Demonstrating Accumulation of Blood in the Posterior Pericardial Space (Arrow) after Acute Aortic Dissection.

Transgastric midpapillary view on transesophageal echocardiography demonstrating accumulation of blood in the posterior pericardial space (arrow) after acute aortic dissection.

Hypertension is the most common comorbid disease in patients with AAD, while hyperlipidemia, tobacco use, and cocaine use are other risk factors. Pregnancy can also increase the risk of AAD, with most females typically presenting during their third trimester or in the early postpartum period. Genetic conditions that increase the risk of AAD are discussed in the previous section. AAD can also occur iatrogenically during cardiac surgery, cardiac catheterization, and insertion of an intra-aortic balloon pump.

Patients with AAS classically report severe "sharp" or "stabbing" pain in the chest or back. Depending on the extent of aortic involvement, other signs and symptoms include diastolic murmur of AI (present in 44% of cases), gastrointestinal bleeding, bowel ischemia, dysphagia, dyspnea, hemoptysis, hoarseness, Horner syndrome, paraplegia, shock, SVC syndrome, and syncope. In roughly 6% of cases, the aortic dissection is painless and presents as new-onset heart failure, stroke, or syncope. These patients tend to have diabetes mellitus, a history of aortic aneurysm, or a history of prior cardiac surgery.

CT is the preferred diagnostic imaging modality, although TEE and MRI are also highly sensitive and specific for diagnosis. TEE may be preferred in unstable patients or those with a history of an iodinated contrast reaction. If left untreated, AAD of the ascending aorta has a high mortality of 1% to 2% per hour after symptom onset, which increases in the presence of complications. In contrast, patients with uncomplicated acute type B aortic dissection (TBAD) have a 30-day mortality rate of 10%, which rises considerably if malperfusion of aortic branch vessels occurs.

References

- Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J 3rd, et al; Peer Review Committee Members. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2022;146:e334-e482.

- Ivascu NS, Skubas NJ. Aortic intramural hematoma: echocardiographic characteristics. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:286-288.

- Ramanath VS, Oh JK, Sundt TM III, et al. Acute aortic syndromes and thoracic aortic aneurysm. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:465-481.

- Tsai TT, Trimarchi S, Nienaber CA. Acute aortic dissection: perspectives from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37:149-159.