- Chapter 6 History and Evolution of Nursing Informatics

- Chapter 7 Nursing Informatics as a Specialty

- Chapter 8 Legislative Aspects of Nursing Informatics: HIPAA, HITECH, and Beyond

Nursing informatics (NI) is the synthesis of nursing science, information science, computer science, and cognitive science for the purpose of managing and enhancing healthcare data, information, knowledge, and wisdom to improve patient care and the nursing profession. In Section I, Building Blocks of Nursing Informatics, the reader learned about the four sciences of NI, also referred to as the four building blocks, and the ethical application of these sciences to manage patient information. Nursing knowledge workers must be able to understand the evolving specialty of NI to harness and use the tools available for managing the vast amount of healthcare data and information. It is essential that NI capabilities be appreciated, promoted, expanded, and advanced to facilitate the work of the nurse, improve patient care, and enhance the nursing profession.

This section presents an overview of NI, informatics education and competencies, informatics as a specialty practice, and legislation that governs informatics and healthcare technology. Chapter 6, History and Evolution of Nursing Informatics, begins this exploration by providing the historical development and evolution of NI, which transitions into Chapter 7, Nursing Informatics as a Specialty, in which the reader learns about NI roles, competencies, and skills. Chapter 8, Legislative Aspects of Nursing Informatics: HIPAA, HITECH, and Beyond, considers the evolving NI needs of nurses and nurse informaticists, based on the current regulations affecting the healthcare arena.

In Chapter 6, History and Evolution of Nursing Informatics, interrelationships among major NI concepts are discussed. As data are transformed into information and information into knowledge, increasing complexity and interrelationships ensue. The boundaries between concepts can become blurred, and feedback loops from one concept level to another evolve. Structured languages and human-computer interaction concepts, which are critical elements for NI, are noted in this chapter. Taxonomies and other current structured languages for nursing are listed. Human-computer interaction concepts are briefly defined and discussed because they are critical to the success of informatics solutions. Importantly, the construct of decision-making is added to the traditional nursing metaparadigms: nurse, person, health, and environment. Decision-making is not only at the crux of nursing practice in all settings and roles but is also a fundamental concern of NI. The work of nursing is centered on the concepts of NI: data, information, knowledge, and wisdom. Information technology (IT) per se is not the focus. Instead, the focus is on the information that the technology conveys. Moreover, NI is no longer the domain of experts in the IT field. More interesting, one does not need technology to perform informatics. The centerpiece of informatics is the manipulation of data, information, and knowledge, especially related to decision-making in any aspect of nursing or in any setting. In a way, all nurses are already informatics nurses. Note that the core concepts and competencies of informatics are particularly well suited to a model of interprofessional education. Ideally, when educational programs are emulating clinical settings, informatics knowledge should be integrated with the processes of interprofessional teams and decision-making. Because simulation laboratories are becoming increasingly common fixtures in the delivery of health-related professional education, they provide a perfect opportunity to incorporate the electronic health record (EHR) applications. The learning laboratory for nursing education will then more closely approximate the IT-enabled clinical settings that are emerging in the real world. A presumption is often made that future graduates will be more computer literate than nurses currently in practice. Although this may be true, computer literacy, or the comfort level someone has with using computer programs and applications, does not equate to an understanding of the facilitative and transformative role of IT. It is essential that the future curricula of basic nursing programs embed the concepts of the role of IT in supporting clinical care delivery. The need for standardizing nursing terminology is also discussed in this chapter as a way to improve the clinical support functions of the EHR. The healthcare industry employs the largest number of knowledge workers-a fact that has resulted in the realization that healthcare administrators must begin to change the way they look at their employees. Nurses and physicians are bright, highly skilled, and dedicated to giving the best patient care. Administrators who tap into this wealth of knowledge find that patient care becomes safer and more efficient.

Chapter 7, Nursing Informatics as a Specialty, discusses NI as a relatively new nursing specialty that combines the building block sciences covered earlier in the text. Combining these sciences results in nurses being able to care for their patients effectively and safely because the information that they need is readily available. Nurses have been actively involved in NI since computers were introduced into health care. With the advent of EHRs, it became apparent that nursing needed to develop its own language for this evolving field. NI was instrumental in assisting in nursing language development. NI is governed by standards established by the American Nurses Association and is a very diverse field, which results in many nurse informaticist specialists becoming focused on one segment of NI. Although NI is a recognized specialty area of practice, in the future all nurses will be expected to have some knowledge of the field, as discussed in Chapter 6, History and Evolution of Nursing Informatics. NI competencies have been developed to ensure that all entry-level nurses are ready to enter a field that is becoming more technologically advanced. The competencies may also be used to determine the educational needs of currently practicing nurses as well as NI specialists. NI specialists no longer must enter the field solely through on-the-job exposure but can now obtain an advanced degree in NI at many well-established universities throughout the United States. NI has grown tremendously as a specialty since its inception and is predicted to continue growing.

Chapter 8, Legislative Aspects of Nursing Informatics: HIPAA, HITECH, and Beyond, provides insights into the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) rules and an overview of the rules associated with technology implementation as defined by the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act. Equally important in informatics practice is a thorough understanding of current legislation and regulations that shape 21st-century practice. The information provided in this text reflects current rules that were in effect at the time of publication. The reader should follow the development of rules and the evolution of informatics legislation at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website (www.hhs.gov) to obtain the most current information related to health information management.

There is an emerging global focus on IT to support clinical care and on the potential benefits for clinicians and patients. In the future, nurses will likely have sufficient computing power at their disposal to aggregate and transform additional multidimensional data and information sources (e.g., historical, multisensory, experiential, and genetic) into a clinical information system to engage with individuals, families, and groups in ways not yet imagined. Every nurse's practice will make contributions to new nursing knowledge in these dynamically interactive clinical information system environments. With the right tools to support the management of data, complex information processing, and ready access to knowledge, the core concepts and competencies associated with informatics will be embedded in the practice of every nurse, whether administrator, researcher, educator, or practitioner. IT is not a panacea, but it provides the profession with unprecedented capacity to generate and disseminate new knowledge more rapidly.

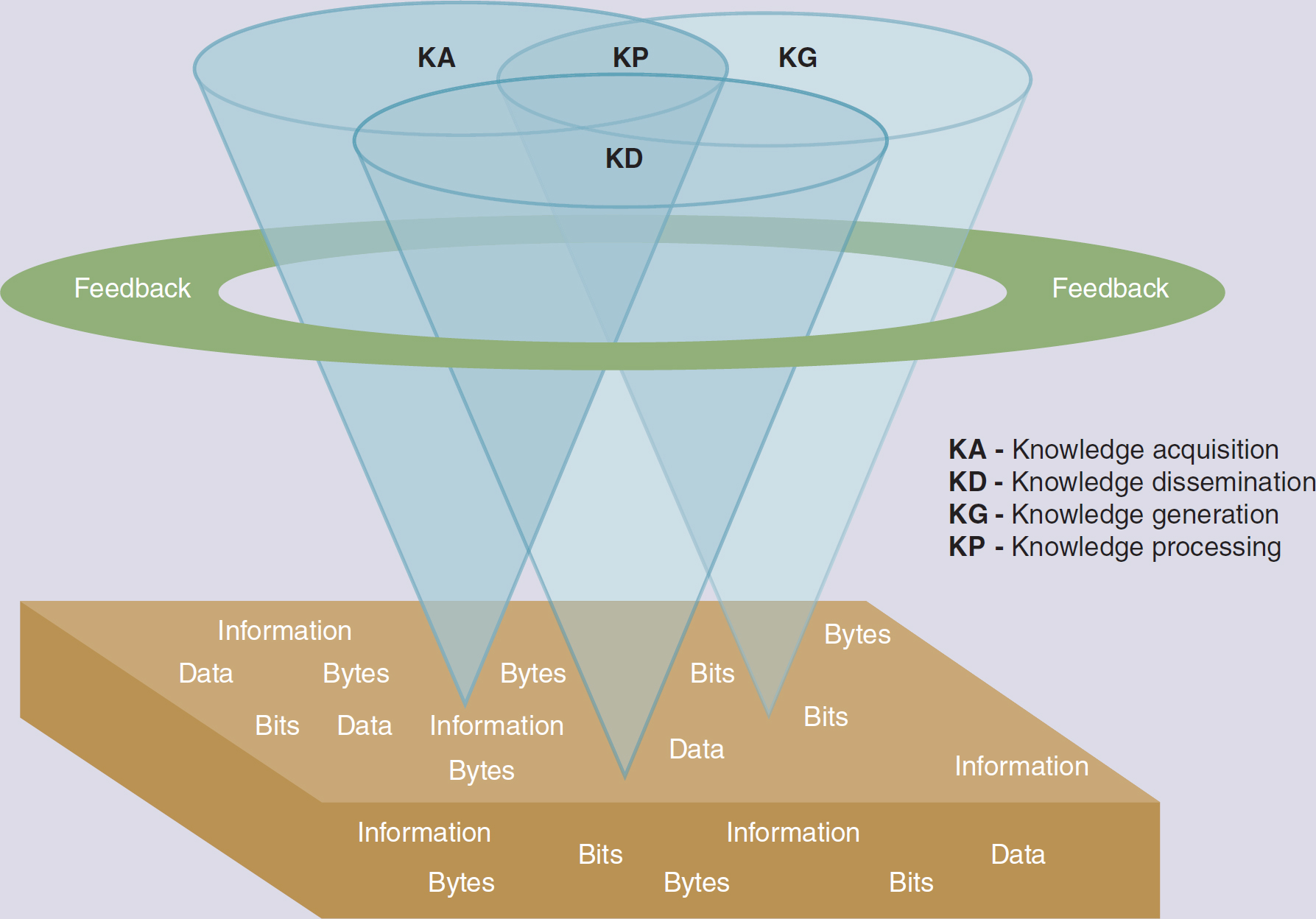

The material in this text is placed within the context of the Foundation of Knowledge model (Figure II-1) to meet the needs of healthcare delivery systems, organizations, patients, and nurses. Through involvement in NI and learning about this evolving specialty, one will be able to use the current theories, architecture, and tools while beginning to challenge what is known. This questioning and search for what could be will provide the basis for the future landscape of nursing. By using the Foundation of Knowledge model as an organizing framework for this text, the authors have attempted to capture this process.

Figure II-1 Foundation of Knowledge Model

An illustration depicts the structure of the Foundation of Knowledge model.

The model features a three-dimensional illustration of three entwined, inverted cones labeled K A, K G, and K D. The three labeled cones converge to create a new cone labeled K P. Encircling these cones is a feedback loop. The entire composition is situated on a platform featuring repeated words such as information, data, bytes, and bits. K A indicates knowledge acquisition; K D indicates knowledge dissemination; K G indicates knowledge generation; and K P denotes knowledge processing.

Designed by Alicia Mastrian

In this section, readers learn about NI. Those readers who are beginning their education will consciously focus on input and knowledge acquisition to glean as much information and knowledge as possible. As these readers become more comfortable in their clinical setting and with nursing science, they will begin to perform some of the other knowledge functions. Experienced nurses, also known as seasoned nurses, question what is known and search for ways to enhance their knowledge and the knowledge of others. What is not available must be created. Through these leaders, researchers, or clinicians, new knowledge is generated and disseminated, and nursing science is advanced. Sometimes, however, to keep up with the explosion of information in nursing and health care, one must continue to rely on the knowledge generated and disseminated by others. In this sense, nurses are committed to lifelong learning and the use of knowledge in the practice of nursing science. How nurses interact within their environment and apply what is learned denotes where they are in the ongoing process captured in the Foundation of Knowledge model; they can be acquiring knowledge, processing knowledge, generating knowledge, and/or disseminating knowledge.

Readers of this section are challenged to ask how they can (1) apply knowledge gained from the practice setting to benefit patients and enhance their practice; (2) help colleagues and patients understand and use current technology; and (3) use wisdom to help create the theories, tools, and knowledge of the future.