Objectives ⬇

- Define nursing science and its relationship to nursing informatics.

- Introduce the Foundation of Knowledge model as the organizing conceptual framework for the text.

- Explore the complex relationships among nursing informatics principles, concepts of knowledge, and knowledge co-creation.

Key Terms ⬆ ⬇

Introduction ⬆ ⬇

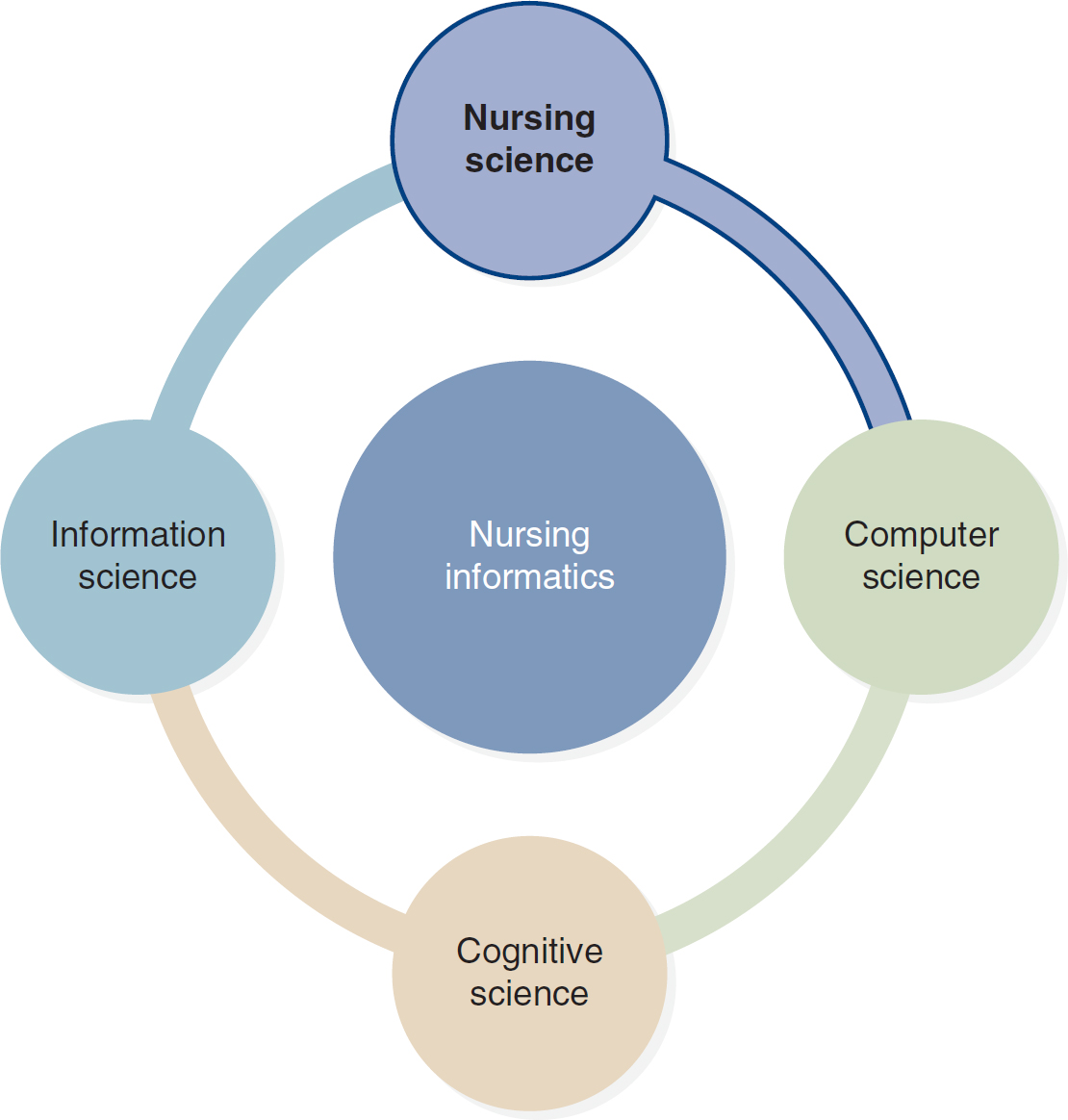

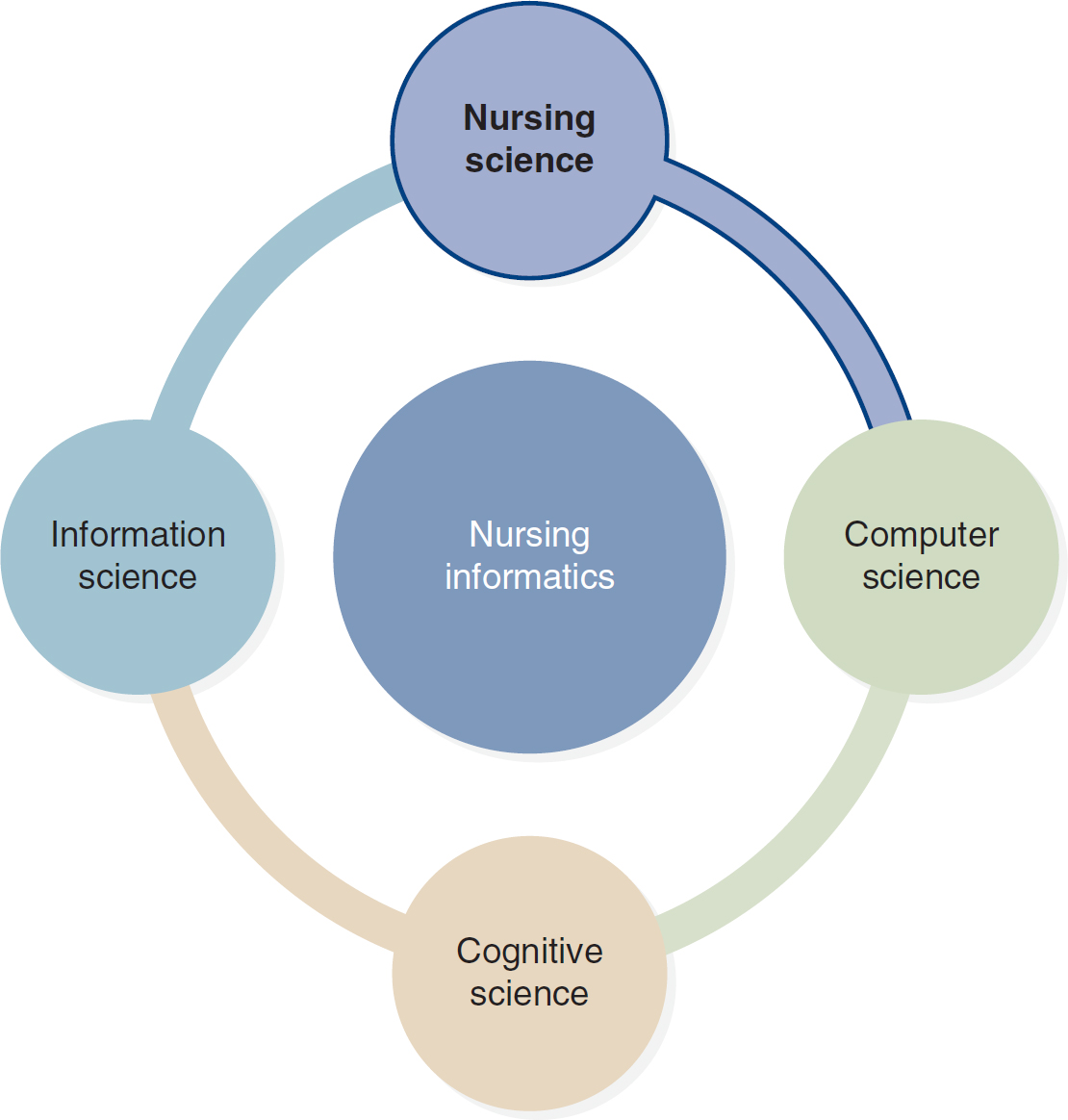

Nursing informatics (NI) has been traditionally defined as a specialty that integrates nursing science, computer science, and information science to manage and communicate data, information, knowledge, and wisdom in nursing practice. This chapter focuses on nursing science as one of the building blocks of NI. As depicted in Figure 1-1, the traditional definition of NI is extended in this text to include cognitive science. The Foundation of Knowledge model is also introduced as the organizing conceptual framework of this text, and the model is tied to nursing science and the practice of NI. We conclude the chapter with an overview of key knowledge concepts and establish that nurses are knowledge workers.

Figure 1-1 Building Blocks of Nursing Informatics

The four building blocks of nursing informatics include nursing science, computer science, cognitive science, and information science.

Nursing Science ⬆ ⬇

Consider the following patient care scenario as a basis for understanding nursing science:

Tom H. is a registered nurse in a busy metropolitan hospital emergency room. He has just admitted a 79-year-old man whose wife brought him to the hospital because he is having trouble breathing. Tom immediately clips a pulse oximeter to the patient's finger and quickly assesses the patient's other vital signs. He discovers a rapid pulse rate and a decreased oxygen saturation level in addition to rapid and labored breathing. Tom determines that the patient is not in immediate danger and that he does not require intubation. Tom focuses his initial attention on easing the patient's labored breathing by elevating the head of the bed and initiating oxygen treatment; he then hooks the patient up to a heart monitor. Tom continues to assess the patient's breathing status as he performs a head-to-toe assessment of the patient that leads to the nursing diagnoses and additional interventions necessary to provide comprehensive care to this patient.

Consider Tom's actions and how and why he intervened as he did. Tom relied on the immediate data and information that he acquired during his initial rapid assessment to deliver appropriate care to his patient. Tom also used technology (a pulse oximeter and a heart monitor) to assist with and support the delivery of care. What is not immediately apparent, and some would argue is transparent (done without conscious thought), is the fact that during the rapid assessment, Tom reached into his knowledge base of previous learning and experiences to direct his care so that he could act with transparent wisdom. He used both nursing theory and borrowed theory to inform his practice. Tom certainly used the nursing process theory, and he may have also used one of several other nursing theories, such as Rogers's science of unitary human beings, Orem's theory of self-care deficit, or Roy's adaptation theory. In addition, Tom may have applied his knowledge from some of the basic sciences, such as anatomy, physiology, psychology, and chemistry, as he determined the patient's immediate needs. Information from Maslow's hierarchy of needs, Lazarus's transaction model of stress and coping, and the health belief model may have also helped Tom practice professional nursing. He gathered data and then analyzed and interpreted those data to form a conclusion-the essence of science. Tom illustrates the practical aspects of nursing science.

The focus of nursing is on human responses to actual or potential health problems and advocacy for various clients. These human responses are varied and may change over time in a single case. Nurses must possess the technical skills to manage equipment and perform procedures; the interpersonal skills to interact appropriately with people; and the cognitive skills to observe, recognize, collect, analyze, and interpret data to reach a reasonable conclusion, which forms the basis of a decision. At the heart of each of these skills lies the management of data and information. Nursing science focuses on the ethical application of knowledge acquired through education, research, and practice to provide services and interventions to patients to maintain, enhance, or restore their health and to acquire, process, generate, and disseminate nursing knowledge to advance the nursing profession.

Nursing is an information-intensive profession. The steps of using information, applying knowledge to a problem, and acting with wisdom form the basis of nursing science practice. Information is composed of data that were processed using knowledge. For information to be valuable, it must be accessible, accurate, timely, complete, cost-effective, flexible, reliable, relevant, simple, verifiable, and secure. Knowledge is the awareness and understanding of a set of information and ways that this information can be made useful to support a specific task or arrive at a decision. In the case scenario, Tom used accessible, accurate, timely, relevant, and verifiable data and information. He compared that data and information to his knowledge base of previous experiences to determine which data and information were relevant to the current case. By applying his previous knowledge to data, he converted those data into information and information into new knowledge-that is, an understanding of which nursing interventions were appropriate in this case. Thus, information is data made functional through the application of knowledge.

Humans acquire data and information in bits and pieces and then transform the information into knowledge. The information-processing functions of the brain are frequently compared to those of a computer and vice versa. (See a discussion of cognitive informatics in Chapter 4, Introduction to Cognitive Science and Cognitive Informatics, for more information.) Humans can be thought of as organic information systems that are constantly acquiring, processing, and generating information or knowledge in their professional and personal lives. They have an amazing ability to manage knowledge. This ability is learned and honed from birth as individuals make their way through life interacting with the environment and being inundated with data and information. Each person experiences the environment and learns by acquiring, processing, generating, and disseminating knowledge.

Tom, for example, acquired knowledge in his basic nursing education program and continues to build his foundation of knowledge by engaging in such activities as reading nursing research and theory articles, attending continuing education programs, consulting with expert colleagues, and using clinical databases and clinical practice guidelines. As he interacts in the environment, he acquires data that must be processed into knowledge. This processing effort causes him to redefine and restructure his knowledge base and generate new knowledge. Tom can then share (disseminate) this new knowledge with colleagues, and he may receive feedback on the knowledge that he shares. This dissemination and feedback build the knowledge foundation anew as Tom acquires, processes, generates, and disseminates new knowledge as a result of his interactions. As others respond to his knowledge dissemination and he acquires yet more knowledge, he is engaged to rethink, reflect on, and reexplore his knowledge acquisition, leading to further processing, generating, and then disseminating knowledge. It should be clear at this point that knowledge management is a fundamental part of nursing science. What will become even clearer as the text unfolds is how informatics supports knowledge management.

Foundation of Knowledge Model ⬆ ⬇

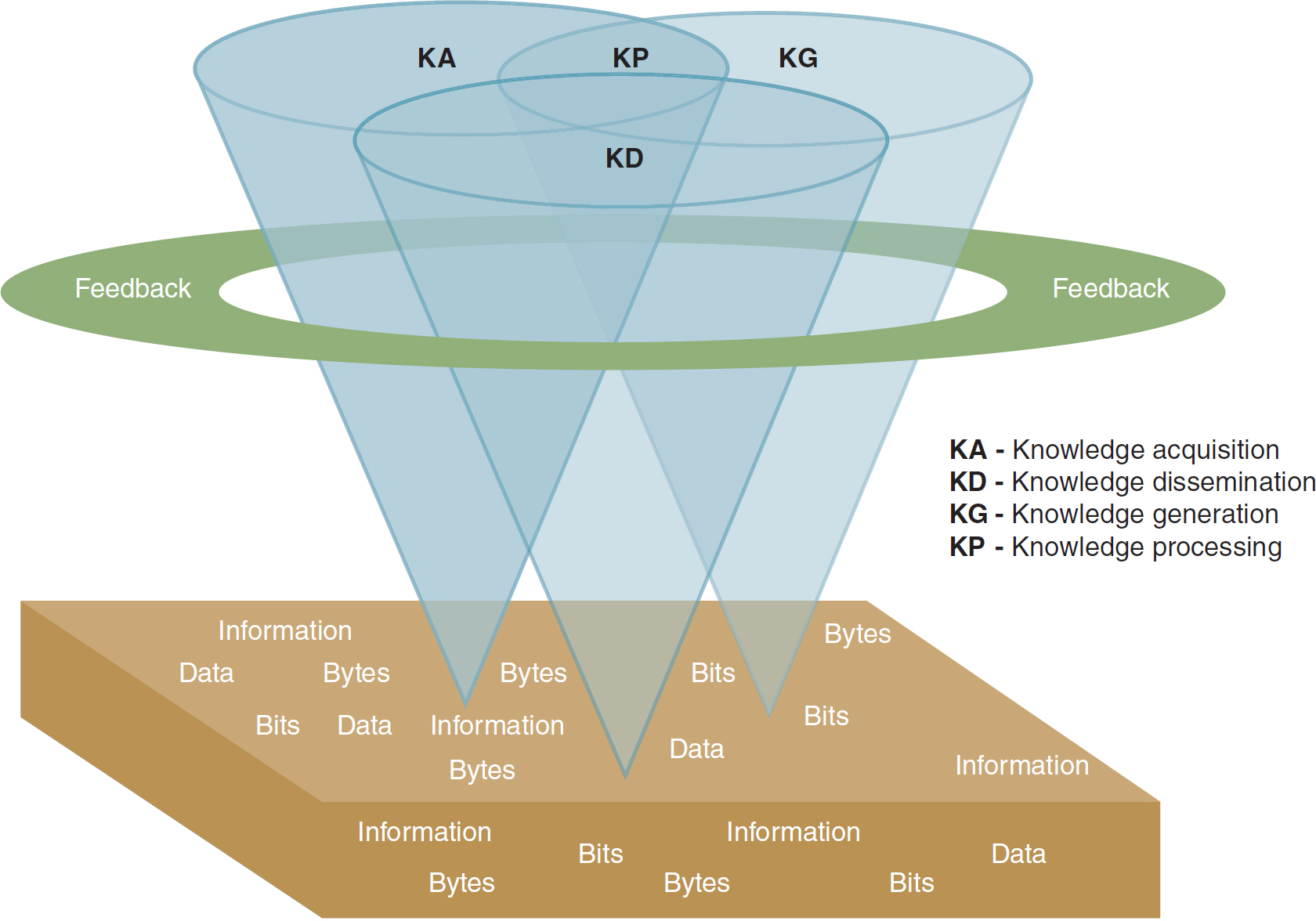

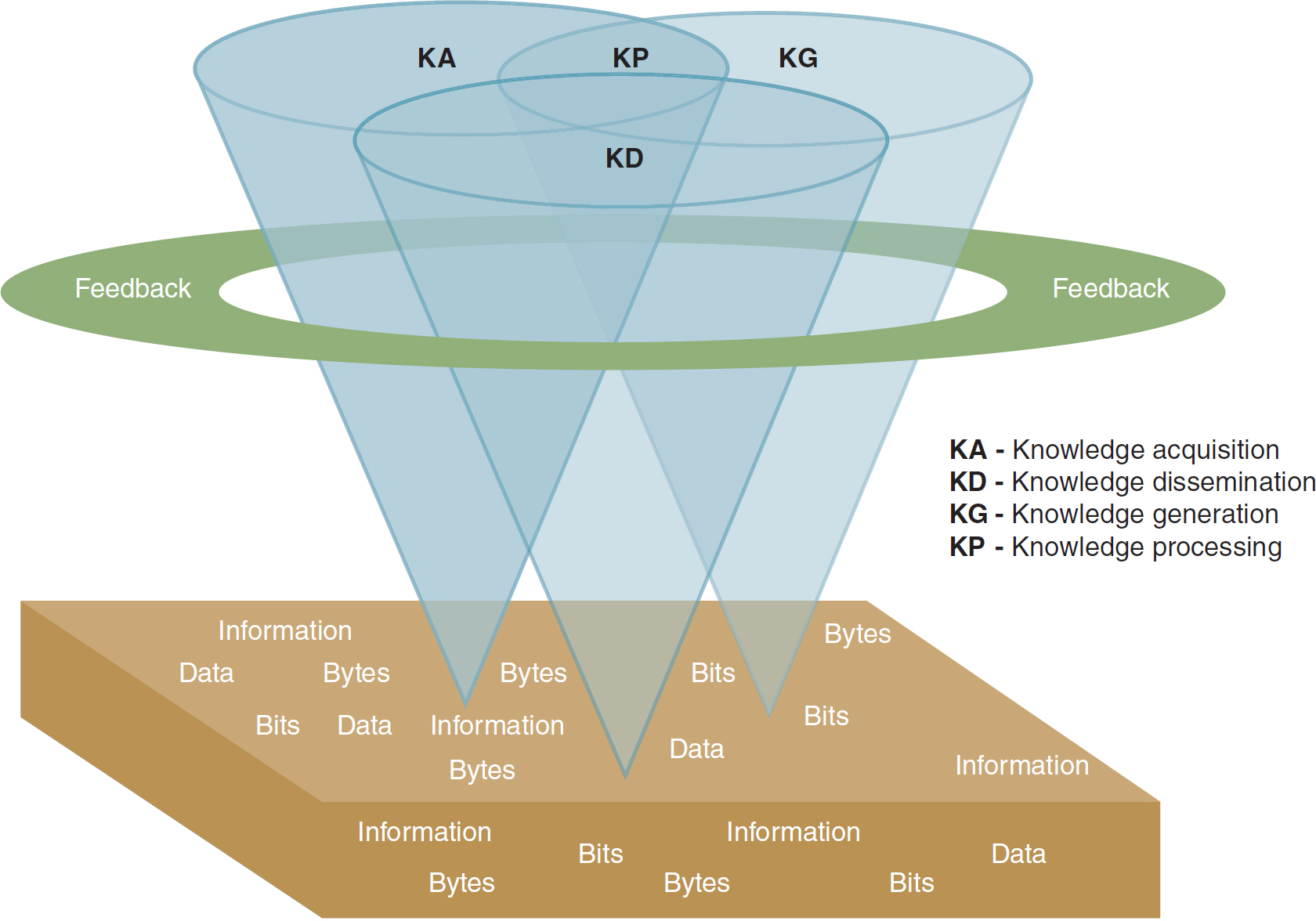

We developed the Foundation of Knowledge model to illustrate these ongoing knowledge processes. The model (Figure 1-2) is used as an organizing framework for this text and as a way to help the reader focus on how we develop and use an individual knowledge base.

Figure 1-2 Foundation of Knowledge Model

An illustration depicts the structure of the Foundation of Knowledge model.

The model features a three-dimensional illustration of three entwined, inverted cones labeled K A, K G, and K D. The three labeled cones converge to create a new cone labeled K P. Encircling these cones is a feedback loop. The entire composition is situated on a platform featuring repeated words such as information, data, bytes, and bits. K A indicates knowledge acquisition; K D indicates knowledge dissemination; K G indicates knowledge generation; and K P denotes knowledge processing.

Designed by Alicia Mastrian

At its base, the model contains bits, bytes (computer terms used to quantify data), data, and information in a random representation. Growing out of the base are separate cones of light that expand as they reflect upward; these cones represent knowledge acquisition, knowledge generation, and knowledge dissemination. At the intersection of the cones and forming a new cone is knowledge processing. Encircling and cutting through the knowledge cones is feedback, which acts on and may transform any or all aspects of knowledge represented by the cones. One should imagine the model as a dynamic figure in which the cones of light and the feedback rotate and interact rather than remaining static. Knowledge acquisition, knowledge generation, knowledge dissemination, knowledge processing, and feedback are constantly evolving for nursing professionals. The transparent effect of the cones is deliberate and intended to suggest that as knowledge grows and expands, its use becomes more transparent, meaning people use this knowledge during practice without even being consciously aware of which aspect of knowledge they are using at any given moment.

To simplify the understanding of the Foundation of Knowledge model, it may be helpful to think back on an early learning experience. Recall the first time you got behind the wheel of a car. There was so much to remember to do and so much to pay attention to, especially if you wanted to avoid an accident. You had to think about how to start the car, adjust the mirrors, fasten the seat belt, and shift the car into gear. You had to take in data and information from friends and family members who tried to “tell” you how to drive. They disseminated knowledge, and you acquired it. And they most likely provided lots of feedback about your driving. As you drove down the street, you also had to notice multiple bits of data in the environment, such as stop signs, traffic signals, turn signals, and speed limit signs, and try to interpret these environmental data into usable information for the current situation. You had to pay attention to several things simultaneously to drive safely. As your confidence grew with experience, you were able to drive more effectively and generate new knowledge about driving that became part of your personal knowledge structure. After many driving experiences, the process of driving became transparent and seamless. Think about this example in relation to a skill that you have acquired or are acquiring in your nursing education. How does or did your learning experience mirror the components of the Foundation of Knowledge model? Experienced nurses, thinking back to their novice years, may recall feeling like their heads were filled with bits of data and information that did not form any type of cohesive whole. As the model depicts, the processing of knowledge begins a bit later (imagine a timeline applied vertically, with early experiences on the bottom and expertise growing as the processing of knowledge ensues). Early on in nurses' education, conscious attention is focused mainly on knowledge acquisition, and beginning nurses depend on their instructors and others to process, generate, and disseminate knowledge. As nurses become more comfortable with the science of nursing, they begin to independently perform some of the other Foundation of Knowledge functions. However, to keep up with the explosion of information in nursing and health care, they must continue to rely on the knowledge generation of nursing theorists and researchers and the dissemination of their work. In this sense, nurses are committed to lifelong learning and the use of knowledge in the practice of nursing science.

Knowledge management and transfer in healthcare organizations are likely to be studied in greater depth as our understanding of professional knowledge increases and our processes to capture and codify it improve. We must strive to facilitate the data, information, and knowledge exchange in the right format between the right people when they need it to proficiently create value for and add value to the organization (APQC, 2022). The Foundation of Knowledge model is not perfect, and others have developed models of knowledge that are more complex. For example, Evans and Alleyne (2009) constructed the knowledge domain process (KDP) model to represent knowledge construction and dissemination in an organization. Yet they caution as follows:

[T]he KDP model, like all models, is an abstraction aimed at making complex systems more easily understood. While the model presents knowledge processes in a structured and simplified form, the nature and structure of the processes themselves may be open to debate. (p. 148)

As we will learn later in this chapter, getting the knowledge to the user and creating a culture where new knowledge is seamlessly integrated into health care remain a challenge. Mason (2020) offered this insight:

Simply put, knowledge management undertakes to identify what is in essence a human asset buried in the minds and hard drives of individuals working in an organization. Knowledge management also requires a system that will allow the creation of new knowledge, a dissemination system that will reach every employee, with the ability to package knowledge as value-added in products, services and systems. (para. 1)

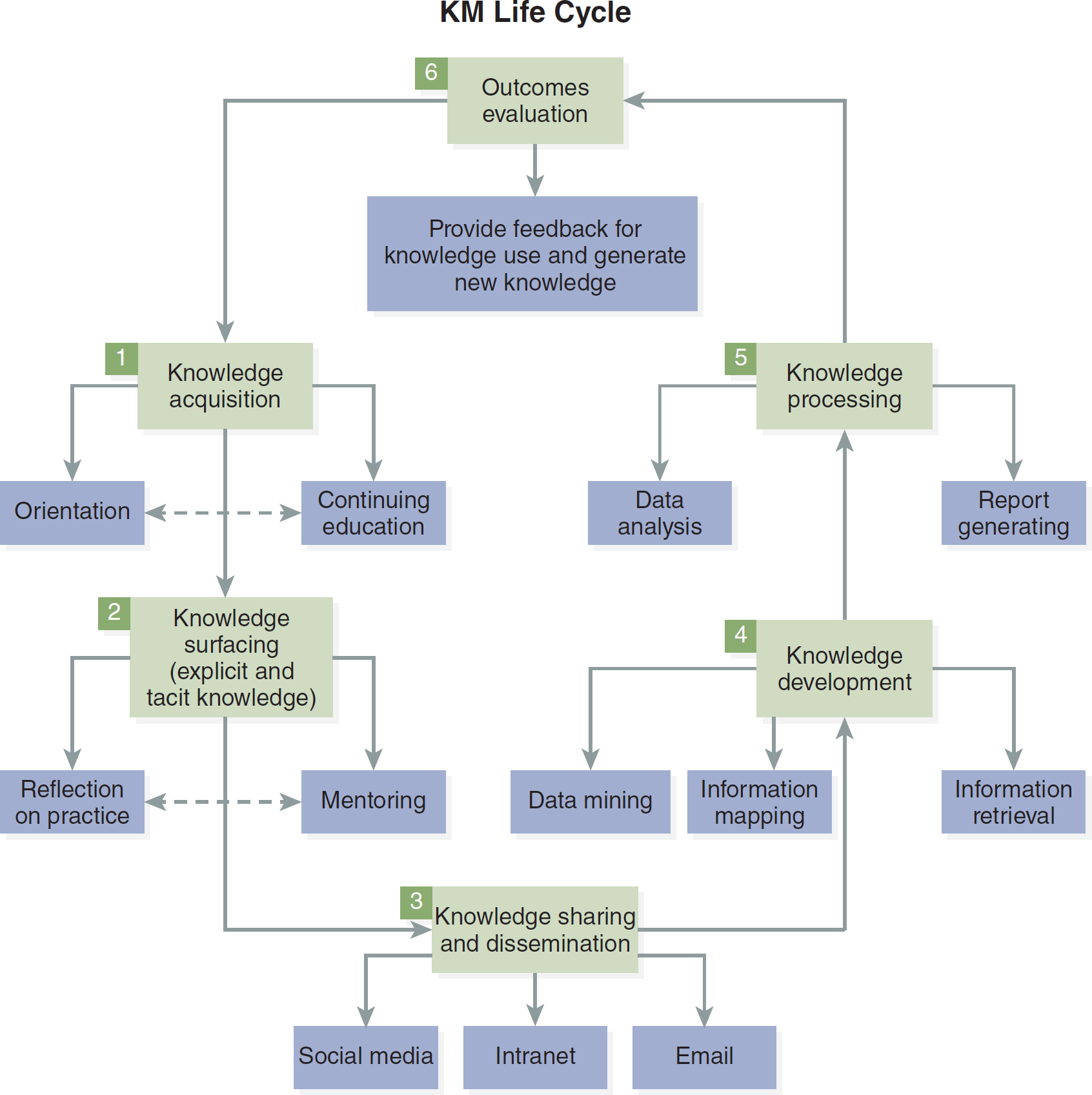

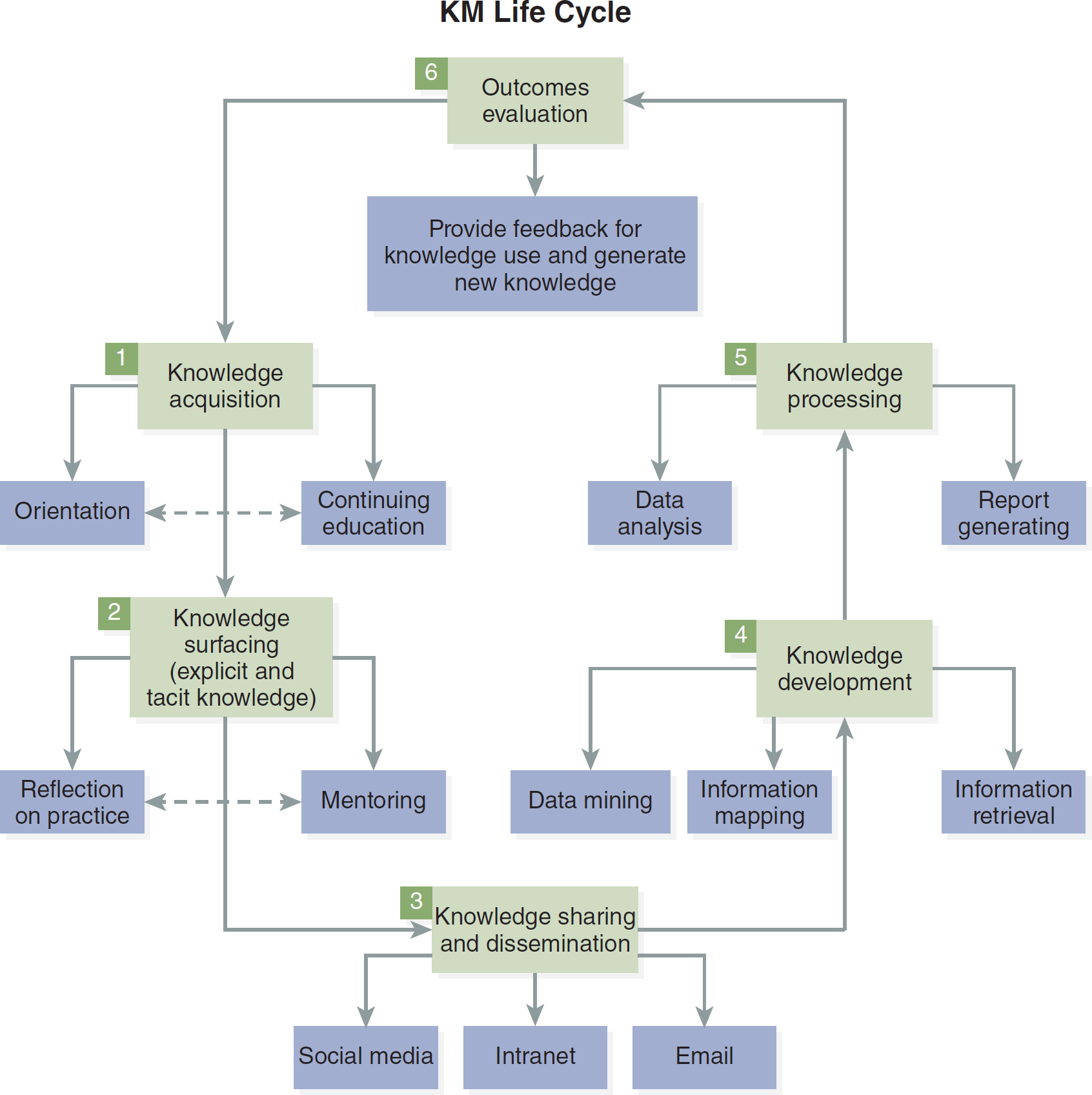

Other impacts that currently challenge knowledge management and will become necessary to synthesize into a comprehensive knowledge management process are the technologies advancing cognitive computing, artificial intelligence (AI), cognitive systems, machine learning, and predictive analytics. These ongoing advancements will “radically transform how we learn and interact in the digital world” and within our organizations (APQC, 2022, para. 18). Figure 1-3 depicts the life cycle of knowledge management in an organization. Note the informatics tools that are integral to knowledge management, particularly in its knowledge dissemination, knowledge development, and knowledge processing aspects.

Figure 1-3 The Knowledge Management Life Cycle

A cyclic flowchart depicts the sequential stages in the knowledge management life cycle.

The stages are as follows. 1. Knowledge acquisition involves orientation and continuing education. 2. Knowledge surfacing encompassing explicit and tacit knowledge includes reflection on practice and mentoring. 3. Knowledge sharing and dissemination includes utilizing social media, intranet, and email. 4. Knowledge development involves activities like data mining, information mapping, and information retrieval. 5. Knowledge processing encompasses data analysis and report generation. 6. Outcomes evaluation involves providing feedback for knowledge use and generating new knowledge. The cycle then returns to the initial stage of knowledge acquisition.

For nurse knowledge workers, information is their primary resource, and when they deal with information, they do so in overlapping phases. That is, the nurses are continually acquiring, processing, assimilating, retaining, and using this information to generate and disseminate knowledge. However, the phases are not sequential; instead, a constant gleaning of data and information from the environment takes place, with the data and information massaged into knowledge bases so that knowledge can be applied and shared (disseminated).

The Foundation of Knowledge model permeates this text, reflecting the understanding that knowledge is a powerful tool and that nurses focus on information as a key building block of knowledge. The application of the model is described to help the reader understand and appreciate the foundation of knowledge in nursing science and see how it applies to NI. All the nursing roles (i.e., practice, administration, education, research, and informatics) involve the science of nursing. Nurses are knowledge workers, working with and generating information and knowledge as a product. They are knowledge acquirers, providing convenient and efficient means of capturing and storing knowledge. They are knowledge users, meaning individuals or groups that benefit from valuable, viable knowledge. Nurses are knowledge engineers, people who design, develop, implement, and maintain knowledge. They are knowledge managers by capturing and processing collective expertise and distributing it where it can create the greatest benefit. Finally, they are knowledge developers and generators, people who change and evolve knowledge based on the tasks at hand and the information available. McGowan et al. (2018) described a similar model, the Knowledge Worker Knowledge Enhancement Process, a process whereby knowledge workers actively seek, apply, embed, and share newly acquired knowledge with others. Knowledge workers “apply their mental competencies” (MasterClass, 2022, para. 1).

More recently introduced in popular literature was the concept of a “learning worker,” one who has the ability to learn quickly and continuously (Salisbury, 2017) and “extract the learning from their work experiences” (Euro Digital Systems, 2021, para. 25), a designation that is not as frequently seen in the popular literature as the term knowledge worker even though many healthcare organizations are transitioning to learning organizations.

In the case scenario, at first glance one might label Tom as a knowledge worker, acquirer, and user. However, stopping there might sell Tom short in his practice of nursing science. Although he acquired and used knowledge to help him achieve his work, he also processed the data and information he collected to develop a nursing diagnosis and a plan of care. The knowledge stores Tom used to develop and glean knowledge from valuable information are generative (having the ability to originate and produce, or generate). For example, Tom may have learned something new about his patient's culture from the patient or his wife, which he will keep by filing it in the knowledge repository of his mind to be used in a similar situation. As he compares this new cultural information to what he already knows, he may gain insight into the effect of culture on a patient's response to illness. In this sense, Tom is a knowledge generator. If he shares this newly acquired knowledge with another practitioner as he records his observations and conclusions, he is then disseminating knowledge. Tom also uses feedback from the various technologies he has applied to monitor his patient's status. In addition, he may rely on feedback from laboratory reports or even other practitioners to help him rethink, revise, and apply the knowledge that he is generating about this patient.

To have ongoing value, knowledge must be viable. Knowledge viability refers to applications (most of them technology based) that offer easily accessible, accurate, and timely information obtained from a variety of resources and methods and presented in a manner so as to provide the necessary elements to generate new knowledge. In the case scenario, Tom may have felt the need to consult an electronic database or a clinical guidelines repository that he has downloaded on his tablet or smartphone or that resides in the emergency room's networked computer system to assist him in the development of a comprehensive care plan for his patient. In this way, Tom uses technology and evidence to support and inform his practice. It is also possible in this scenario that an alert might appear in the patient's electronic health record or in the clinical information system to remind Tom to ask about influenza and pneumonia vaccines. Clinical information technologies that support and inform nursing practice and nursing administration are an important part of NI.

The Nature of Knowledge ⬆ ⬇

Knowledge may be thought of as either explicit or tacit. Explicit knowledge is the knowledge that one can convey in letters, words, and numbers. It can be exchanged or shared in the form of data, manuals, product specifications, principles, policies, and theories. Nurses can disseminate and share this knowledge publicly, or on the record, and scientifically, or methodically. A nursing model or theory that is well developed and easily explained and understood is an example of explicit knowledge. In contrast, tacit knowledge is individualized and highly personal, or private, including one's values or emotions. Knowing intuitively when and how to care is an example of tacit knowledge. This type of knowledge is difficult to convey, transmit, or share with others because it consists of one's own insights, or slant on things; perceptions; intuition; sense; hunches; or gut feelings. Tacit knowledge reflects skills and beliefs, which is why it is difficult to explain or communicate to others.

Farr and Cressey (2015) used grounded theory methodology to study how professionals perceive the quality of their performance, and they found that intangible, tacit knowledge was just as important to the perception of quality of performance as more standardized rational measures of quality based on organizational policy:

This paper illuminates the importance of the tacit, intangible and relational dimensions of quality in actual practice. Staff values and personal and professional standards are core to understanding how quality is co-produced in service interactions. Professional experience, tacit clinical knowledge, personal standards and values, and conversations with patients and families all contributed to how staff understood and assessed the quality of their work in everyday practice. (p. 8)

Along these same lines, references to the co-creation of knowledge have been surfacing in the literature in the last decade. Bagayogo et al. (2014) suggested that knowledge co-creation is increasingly important to innovation in organizations and that knowledge is co-created as individuals collaborate on a shared task and share their experiences and perceptions. They reported on the use of social media support for breast and prostate cancer patients: “Individuals work together and co-create knowledge through a process that evolves temporally and is embedded in a web of interactions. Both temporal and interactional dimensions have been considered in the study of knowledge co-creation” (p. 627). The importance of knowledge cocreation is noted worldwide as evidenced in the program of study for teachers to enhance effective learning in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education in the knowledge co-creation program in Zambia (Ministry of Education, 2022).

How nursing students and practicing nurses learn is directly affected by their practice experiences within their own personal frame of reference. The quality of clinical decision-making is directly related to experience and knowledge. Knowledge is situational. Explicit and tacit knowledge are used to conduct assessments, diagnoses, intervention implementation, and evaluation of nursing actions for each individual patient. Knowledge management systems (KMSs) must blend these knowledge needs and provide knowledge bases and decision support systems to inform clinical decision-making. Each person processes and assimilates knowledge in a unique way, which is influenced by their unique perspective. What is needed is an explicit way of surfacing these nuggets of knowledge so that they can be shared among practitioners.

The Nurse as a Knowledge Worker ⬆ ⬇

As we have already established, all nurses use data and information. This information is then converted to knowledge. The nurse then acts on this knowledge by initiating a plan of care, updating an existing one, or maintaining the status quo. Does this use of knowledge make the nurse a knowledge worker?

The term knowledge worker was first coined by Peter Drucker in his 1959 book, Landmarks of Tomorrow (Drucker, 1996). Knowledge work is defined as nonrepetitive, nonroutine work that entails a significant amount of cognitive activity (Sorrells-Jones & Weaver, 1999). Drucker described a knowledge worker as one who has advanced formal education and can apply theoretical and analytical knowledge. According to Drucker, the knowledge worker must be a continuous learner and a specialist in a field.

Characteristics of Knowledge Workers

According to Gent (2007), there are three types of knowledge workers: (1) knowledge consumers, (2) knowledge brokers, and (3) knowledge generators. This breakdown of knowledge workers is not mutually exclusive; instead, people transition between these states as their situations and experience, education, and knowledge change.

- Knowledge consumers are mainly users of knowledge who do not have the expertise to provide the knowledge they need for themselves. Novice nurses can be thought of as knowledge consumers who use the knowledge of experienced nurses or search information systems for the knowledge necessary to apply to their practice. As responsible knowledge consumers, they must also question and challenge what is known to help them learn and understand. Their questioning and challenging facilitate critical thinking and the development of new knowledge.

- Knowledge brokers know where to find information and knowledge; they generate some knowledge but are mainly known for their ability to find what is needed. More experienced nurses and nursing students become knowledge brokers out of necessity because they need to know something.

- Knowledge generators are the “primary sources of new knowledge” (para. 2). They include nursing researchers and nursing experts-the people who know; they can answer questions, craft theories, find solutions to nursing problems or concerns, and innovate as part of their practice.

As knowledge work continues to stay in the forefront for healthcare professionals, it is important to realize that knowledge work

- grows and evolves with the individual, their profession, and the colleagues who invigorate them and whom they invigorate;

- requires the individual to use their knowledge in interpreting each specific patient context or situation to leverage their wisdom to initiate the appropriate action and continuously reassess the patient or situation; and

- is a catalyst for change and must be shared and honed.

As nursing recognized the knowledge work necessary to improve patient care and enhance the profession, so has medicine. Machin et al. (2022) believed that physicians must be “thinking differently, doing differently, and linking differently. This requires a raised awareness of knowledge work skills, support for their use, and promotion of linked working within communities of practice” (p. 73).

The healthcare industry, nursing profession, and patients all benefit as nurses develop nursing intelligence and intellectual capital by gaining insight into nursing science and its enactment in their practice. NI applications of databases, knowledge management systems, and repositories, where this knowledge can be analyzed and reused, facilitate this process by enabling knowledge to be disseminated and recycled.

Getting to Wisdom ⬆ ⬇

This text provides a framework that embraces knowledge so that readers can develop the wisdom necessary to apply what they have learned. Wisdom is the application of knowledge to an appropriate situation. In the practice of nursing science, one expects actions to be directed by wisdom. Wisdom uses knowledge and experience to heighten common sense and insight to exercise sound judgment in practical matters. It is developed through knowledge, experience, insight, and reflection. Sometimes wisdom is thought of as the highest form of common sense, the result of accumulated knowledge, erudition (i.e., deep, thorough learning), or enlightenment (i.e., education that results in understanding and the dissemination of knowledge). It is the ability to apply valuable and viable knowledge, experience, understanding, and insight while being prudent and sensible. Knowledge and wisdom are not synonymous: Knowledge abounds with others' thoughts and information, whereas wisdom is focused on one's own mind and the synthesis of experience, insight, understanding, and knowledge. Wisdom has been called the foundation of the art of nursing.

Some nursing roles might be viewed as more focused on some aspects than other aspects of the Foundation of Knowledge model. For example, some people might argue that nurse educators are primarily knowledge disseminators and that nurse researchers are knowledge generators. Although the more frequent output of their efforts can certainly be viewed in this way, it is important to realize that nurses use all aspects of the Foundation of Knowledge model, regardless of their area of practice. For nurse educators to be effective, they must be in the habit of constantly building and rebuilding their foundation of knowledge about nursing science. In addition, as they develop and implement curricular innovations, they must evaluate the effectiveness of those changes. In some cases, they use formal research techniques to achieve this goal and therefore generate knowledge about the best and most effective teaching strategies. Similarly, nurse researchers must acquire and process new knowledge as they design and conduct their research studies. All nurses have the opportunity to be involved in the formal dissemination of knowledge via their participation in professional conferences, either as presenters or as attendees. In addition, some nurses disseminate knowledge by formal publication of their ideas. In the case of presenting at conferences or publishing, nurses may receive feedback that stimulates rethinking about the knowledge they have generated and disseminated, which in turn prompts them to acquire and process data and information anew.

Regardless of their practice arena, all nurses must use informatics and technology to inform and support that practice. The case scenario introduced earlier discussed Tom's use of various monitoring devices that provide feedback on the physiological status of the patient. It was also suggested that Tom might consult a clinical database or nursing practice guidelines residing in the cloud (a virtual information storage system) on a tablet or smartphone or on a clinical agency network as he develops an appropriate plan of action for his nursing interventions. Perhaps the clinical information system in the agency supports the collection of data about patients in a relational database, which would provide an opportunity for data mining by nursing administrators or nurse researchers. Data mining provides an opportunity to tease out important relationships to determine best practices to support the delivery of effective care. This text is designed to include the necessary content to prepare nurses for practice in the ever-changing and technology-laden healthcare environments. Informatics competence has been recognized for many years as being necessary to enhance clinical decision-making and improve patient care. NI research should be on the structuring and processing of patient information and the ways that these endeavors inform nursing decision-making in clinical practice. The increased use of technology to enhance nursing practice, nursing education, and nursing research will open new avenues for acquiring, processing, generating, and disseminating knowledge.

In the future, nursing research will make significant contributions to the development of nursing science. Technologies and translational research will abound, and clinical practices will continue to be evidence based, thereby improving patient outcomes and decreasing safety concerns. Schools of nursing will embrace nursing science as they strive to meet the needs of changing student populations and the increasing complexity of healthcare environments.

Summary ⬆ ⬇

Nursing science influences all areas of nursing practice. This chapter provided an overview of nursing science and considered how nursing science relates to typical nursing practice roles, education, informatics, and research. The Foundation of Knowledge model was introduced as the organizing conceptual framework for this text. We reviewed key concepts of knowledge and the characteristics of knowledge workers, thus establishing nurses as knowledge workers. Finally, the relationship of nursing science to NI was discussed. In subsequent chapters, the reader will learn more about how NI supports nurses in their many and varied roles. In an ideal world, nurses would embrace nursing science as knowledge users, knowledge managers, knowledge generators, knowledge engineers, and knowledge workers.

| Thought-Provoking Questions |

|---|

- Imagine you are in a social situation and someone asks you, “What does a nurse do?” Think about how you would capture and convey in your answer the richness that is nursing science.

- Choose a clinical scenario from your recent experience and analyze it using the Foundation of Knowledge model. How did you acquire knowledge? How did you process knowledge? How did you generate knowledge? How did you disseminate knowledge? How did you use feedback, and what was the effect of the feedback on the foundation of your knowledge?

|

References ⬆

- APQC. (2022). What is knowledge management?www.apqc.org/whatisknowledgemanagement

- Bagayogo F., Lapointe L., Ramaprasad J., & Vedel I. (2014, January-6). Co-creation of knowledge in healthcare: A study of social media usage [Session paper]. 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, Hawaii. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2014.84

- Drucker P. F. (1996). Landmarks of tomorrow. Transaction. (Original work published 1959)

- Euro Digital Systems. (2021). Knowledge workers vs. learning workers (pros and cons).www.eurodigitalsystems.co.uk/blog/knowledge-workers-vs-learning-workers-pros-and-cons

- Evans M., & Alleyne J. (2009). The concept of knowledge in KM: A knowledge domain process model applied to inter-professional care. Knowledge and Process Management, 16(4), 147-161. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.331

- Farr M., & Cressey P. (2015). Understanding staff perspectives of quality in practice in healthcare. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0788-1

- Gent A. (2007, October 17). Three types of knowledge workers. Incredibly Dull. http://incrediblydull.blogspot.com/2007/10/three-types-of-knowledge-workers.html

- Machin A., Reeve J., Lyness E., & Reilly J. (2022). Future doctors as knowledge workers. British Journal of General Practice, 72(715), 73. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp22X718397

- Mason M. (2020). Knowledge management: The essence of the competitive edge. www.moyak.com/papers/knowledge-management.html

- MasterClass. (2022). What are knowledge workers? The role of knowledge workers.www.masterclass.com/articles/knowledge-workers#6k3s0g5OZEiQzdkIVTphQd

- McGowan C. G., Reid , K. L. P., & Styger , L. E. J. (2018). The knowledge enhancement process of knowledge workers. Journal of Organizational Psychology, 18(1), 33-41. https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2520&context=buspapers

- Ministry of Education. (2022). Knowledge co-creation programme (KCCP).https://nsc.gov.zm/_kccp/index.php

- Salisbury M. (2017, May 9). Introducing the new learning workers. Association for Talent Development. www.td.org/insights/introducing-the-new-learning-workers

- Sorrells-Jones J., & Weaver D. (1999). Knowledge workers and knowledge-intense organizations, Part 1: A promising framework for nursing and healthcare. Journal of Nursing Administration, 29(7/8), 12-18. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005110-199907000-00008