AUTHOR: Fred F. Ferri, MD

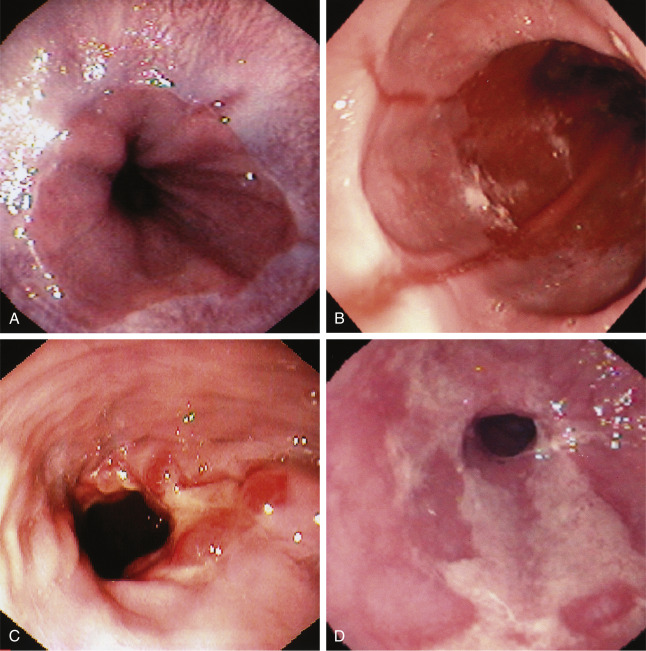

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a motility disorder characterized primarily by heartburn and caused by the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. A current definition is a condition that develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes at least two heartburn episodes per week and/or complications. Table 1 describes a classification system for esophagitis.

TABLE 1 Los Angeles Endoscopic Classification System for Esophagitis

| Grade A | One or more mucosal breaks confined to folds, ≤5 mm | ||

| Grade B | One or more mucosal breaks >5 mm confined to folds but not continuous between the tops of mucosal folds | ||

| Grade C | Mucosal breaks continuous between tops of two or more mucosal folds but not the circumferential | ||

| Grade D | Circumferential mucosal break |

From Feldman M et al: Sleisenger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease, ed 10, Philadelphia, 2016, Elsevier.

- GERD is one of the most prevalent gastrointestinal disorders. It is the most common GI diagnosis recorded during visits to outpatient clinics. From 18% to 28% of adults are affected.

- The estimated prevalence of GERD is 13.3% of the population worldwide and 15.4% in North America. Costs related to GERD in the U.S. are estimated at $10 billion annually.1

- Nearly 7% of persons in the United States have heartburn daily, 20% have it monthly, and 60% have it intermittently. Incidence in pregnant women exceeds 80%.

- Nearly 20% of adults use antacids or over-the-counter H2 blockers at least once a week for relief of heartburn.

- The phenotypic presentations of GERD include nonerosive reflux disease (in 60% to 70% of patients), erosive esophagitis (in 30%), and Barrett esophagus (in 5% to 12%).1

- Physical examination: Generally unremarkable

- Clinical signs and symptoms: Heartburn, dysphagia, sour taste, regurgitation of gastric contents into the mouth

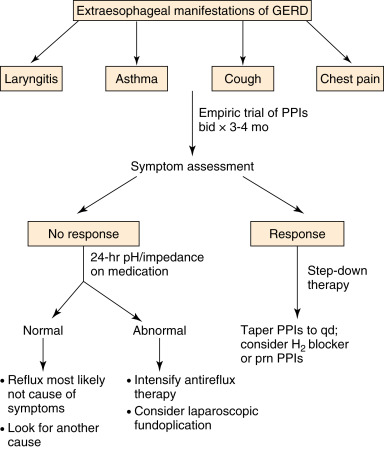

- Chronic cough and bronchospasm

- Chest pain, laryngitis, early satiety, abdominal fullness, and bloating with belching

- Dental erosions in children

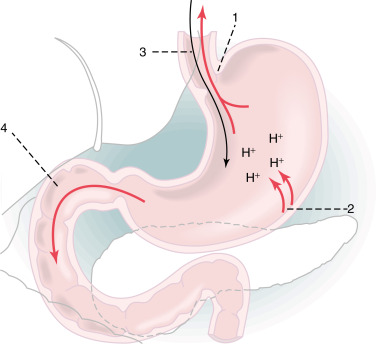

- Incompetent lower esophageal sphincter (LES) (see Fig. E1)

- Medications that lower LES pressure (calcium channel blockers, alpha-adrenergic antagonists, nitrates, theophylline, anticholinergics, sedatives, prostaglandins)

- Foods that lower LES pressure (chocolate, yellow onions, peppermint). Table 2 summarizes modulators of lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure

- Tobacco abuse, alcohol, coffee

- Pregnancy

- Gastric acid hypersecretion

- Hiatal hernia (controversial) present in >70% of patients with GERD; however, most patients with hiatal hernia are asymptomatic

- Obesity is associated with a statistically significant increase in the risk for GERD symptoms, erosive esophagitis, and esophageal carcinoma

TABLE 2 Modulators of Lower Esophageal Sphincter (LES) Pressure

| Increase LES Pressure | Decrease LES Pressure | |

|---|---|---|

| Hormones/peptides | Gastrin | CCK |

| Motilin | Secretin | |

| Substance P | Somatostatin | |

| Vasoactive intestinal peptide | ||

| Neural agents | α-Adrenergic agonists | α-Adrenergic antagonists |

| β-Adrenergic antagonists | β-Adrenergic agonists | |

| Cholinergic agonists | Cholinergic antagonists | |

| Foods and nutrients | Protein | Chocolate |

| Fat | ||

| Peppermint | ||

| Other factors | Antacids | Barbiturates |

| Baclofen | Calcium channel blockers | |

| Cisapride | Diazepam | |

| Domperidone | Dopamine | |

| Histamine | Meperidine | |

| Metoclopramide | Morphine | |

| Prostaglandin F2α | Prostaglandins E2 and I2 | |

| Serotonin | ||

| Theophylline |

CCK, Cholecystokinin.

From Feldman M et al: Sleisenger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease, ed 10, Philadelphia, 2016, Elsevier.

From Andreoli TE et al: Andreoli and Carpenter’s Cecil essentials of medicine, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2010, WB Saunders.