AUTHOR: Jorge Mercado, MD

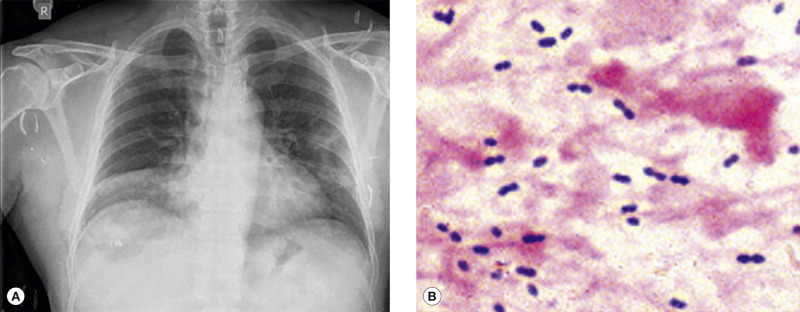

Pneumonia is defined as inflammation of the pulmonary parenchyma caused by an infectious agent (in this case, bacteria). It can be further categorized as community-acquired or health care-associated. The definition of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), traditionally referred to alveolar infection that develops in the outpatient setting or within 48 hr of admission, now includes patients previously categorized as having health care-associated pneumonia (HCAP) since the microbiology and treatment is similar. Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is pneumonia occurring ≥48 h after hospital admission and not incubating at the time of admission.1

Health care-associated pneumonia

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- The annual incidence of pneumonia in the U.S. is 24.8 cases per 10,000 adults, with the highest rates among adults between 65 to 79 yr of age (63 cases per 10,000 adults) and those >80 yr old (164.3 cases per 10,000 adults). Health care expenditures for CAP exceed $10 billion annually.

- Hospitalization rate for pneumonia is 15% to 20%. Incidence is highest among the oldest adults.

- In 2017, the tenth leading cause of mortality in the U.S. reported by the National Center for Health Statistics was influenza and pneumonia together. Deaths per 100,000 population: 15.1.

- Globally, Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) is the most common pathogen causing community-acquired pneumonia.

- Fever, tachypnea, chills, tachycardia, cough, and sometimes pleuritic chest pain (especially if a pleural effusion is present)

- Presentation varies with the cause of pneumonia, the patient’s age, and the clinical situation:

- Patients with streptococcal pneumonia usually present with high fever, chills, atypical chest pain, cough, and copious production of rusty-appearing purulent sputum. Pleurisy in the setting of parapneumonic effusions can also occur. Potential complications include bacteremia, empyema, and distant infections (e.g., meningitis).

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae: Insidious onset; headache; dry, paroxysmal cough that is worse at night; myalgias; malaise; sore throat; extrapulmonary manifestations (e.g., erythema multiforme, aseptic meningitis, urticaria, erythema nodosum) may be present. (See chapter on “Mycoplasma Pneumonia.”)

- Chlamydia pneumoniae: Persistent, nonproductive cough, low-grade fever, headache, sore throat.

- Legionella pneumophila: High fever, mild cough, mental status change, myalgias, diarrhea, respiratory failure. (See chapter on “Legionnaires Disease.”)

- MRSA pneumonia: Often preceded by influenza, may present with shock and respiratory failure.

- Elderly or immunocompromised hosts with pneumonia may initially present with only minimal symptoms (e.g., low-grade fever, confusion); respiratory and nonrespiratory symptoms are less commonly reported by older patients with pneumonia.

- In general, auscultation of lungs in patients with pneumonia reveals crackles/rhonchi and diminished breath sounds. Egophany may also be present.

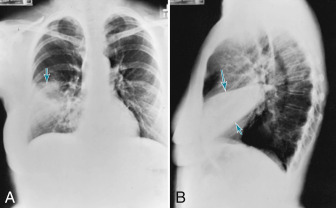

- Dullness on percussion or decreased fremitus may be an indication that a pleural effusion is present.

- Table 1 summarizes common pathogens causing CAP

- Streptococcus pneumoniae (5% to 15% of hospitalized CAP cases): Incidence has been declining due to widespread use of pneumococcal vaccination and reduced rate of cigarette smoking

- Haemophilus influenzae (3% to 10% of CAP cases)

- L. pneumophila (1% to 5% of adult pneumonias) (2% to 8% of CAP cases)

- Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli

- Staphylococcus aureus (3% to 5% of CAP cases)

- Atypical organisms such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Legionella pneumophila implicated in up to 40% of cases of CAP

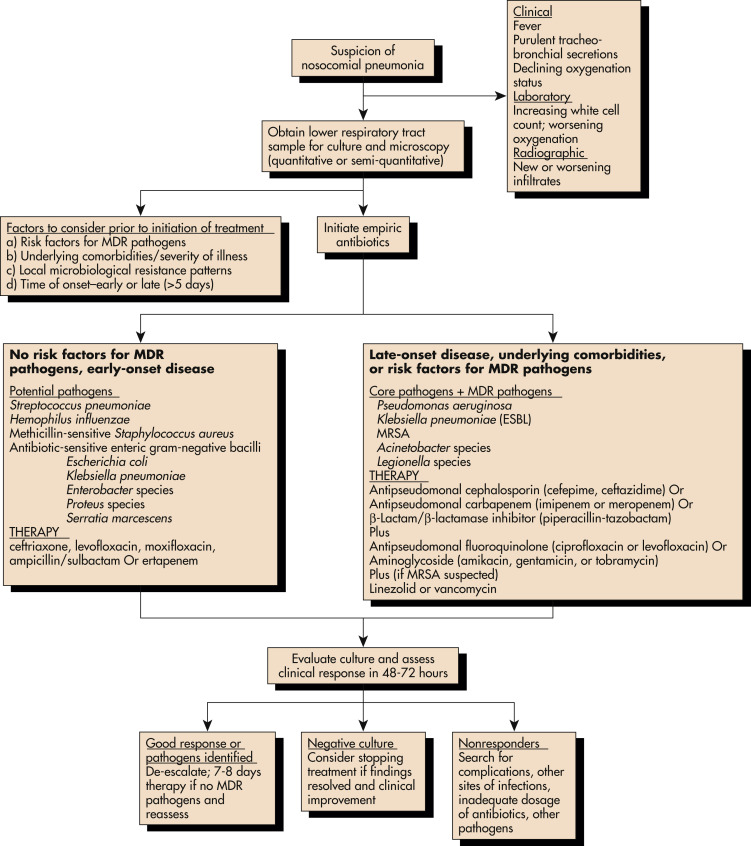

- Gram-negative organisms cause >80% of nosocomial pneumonias

- Predisposing factors (Table 2 and Table 3):

- Influenza infection is one of the important predisposing factors to S. pneumoniae and S. aureus pneumonia

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: H. influenzae, S. pneumoniae, Legionella, Moraxella catarrhalis

- Seizures: Aspiration pneumonia

- Compromised hosts: Legionella, gram-negative organisms

- Alcoholism: K. pneumoniae, S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae

- HIV: S. pneumoniae

- IV drug addicts with right-sided bacterial endocarditis: S. aureus

- Older patient with comorbid diseases: C. pneumoniae

TABLE 2 Risk Factors for Developing Severe Community-Acquired Pneumonia

| Advanced age Comorbid illness (e.g., chronic respiratory illness, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, neurologic illness, renal insufficiency, malignancy) Cigarette smoking Alcohol abuse Absence of antibiotic therapy before hospitalization Failure to contain infection to its initial site of entry Immune suppression Genetic polymorphisms in the immune response |

From Vincent JL et al: Textbook of critical care, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2017, Elsevier.

TABLE 3 Clinical Associations With Specific Pathogens

| Condition | Commonly Encountered Pathogens | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcoholism | Streptococcus pneumoniae (including penicillin-resistant), anaerobes, gram-negative bacilli (possibly Klebsiella pneumoniae), tuberculosis | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/current or former smoker | S. pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis | ||

| Residence in nursing home | S. pneumoniae, gram-negative bacilli, H. influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, Chlamydophila pneumoniae; consider M. tuberculosis. Consider anaerobes, but these are less common | ||

| Poor dental hygiene | Anaerobes | ||

| Bat exposure | Histoplasma capsulatum | ||

| Bird exposure | Chlamydophila psittaci, Cryptococcus neoformans, H. capsulatum | ||

| Rabbit exposure | Francisella tularensis | ||

| Travel to southwestern United States | Coccidioidomycosis; hantavirus in selected areas | ||

| Exposure to farm animals or parturient cats | Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) | ||

| Postinfluenza pneumonia | S. pneumoniae, S. aureus (including the community-acquired strain of methicillin-resistant S. aureus), H. influenzae | ||

| Structural disease of the lung (e.g., bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pseudomonas cepacia, or S. aureus | ||

| Sickle cell disease, asplenia | Pneumococcus, H. influenzae | ||

| Suspected bioterrorism | Anthrax, tularemia, plague | ||

| Travel to Asia | Severe acute respiratory syndrome, tuberculosis, melioidosis |

From Vincent JL et al: Textbook of critical care, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2017, Elsevier.

TABLE 1 Common Pathogens Causing Community-Acquired Pneumonia

| Inpatient, With No Cardiopulmonary Disease or Modifying Factors | |||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, mixed infection (bacteria plus atypical pathogen), viruses (including influenza), Legionella spp., and others (Mycobacterium tuberculosis, endemic fungi, Pneumocystis jirovecii) | |||

| Inpatient, With Cardiopulmonary Disease and/or Modifying Factors | |||

| All of the above, but drug-resistant S. pneumoniae (DRSP) and enteric gram-negative organisms are more of a concern | |||

| Severe Community-Acquired Pneumonia, With No Risks for Pseudomonas Aeruginosa | |||

| S. pneumoniae (including DRSP), Legionella spp., H. influenzae, enteric gram-negative bacilli, Staphylococcus aureus (including methicillin-resistant S. aureus), M. pneumoniae, respiratory viruses (including influenza), others (C. pneumoniae, M. tuberculosis, endemic fungi) | |||

| Severe CAP, With Risks for P. Aeruginosa | |||

| All of the pathogens above plus P. aeruginosa |

From Vincent JL et al: Textbook of critical care, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2017, Elsevier.