Author: Glenn G. Fort, MD, MPH

Acute viral encephalitis is an acute febrile syndrome with evidence of meningeal involvement and of derangement of the function of the cerebrum, cerebellum, or brain stem.

- Arboviral encephalitis

- Brain stem encephalitis

- Acute necrotizing encephalitis

- Rasmussen encephalitis

- Encephalitis lethargica

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

About 20,000 cases/yr are reported to the CDC. West Nile infection is the most common arborvirus encephalitis in the U.S. being reported in 49/50 states in 2021 with 2445 cases and 165 deaths (6.8%). Each year in the U.S. approximately seven patients are hospitalized for encephalitis per 100,000 population.

- Arbovirus infections are transmitted by mosquitoes and thus cause infection when mosquitoes are active, especially summer and fall. Herpes simplex infections can occur at any time.

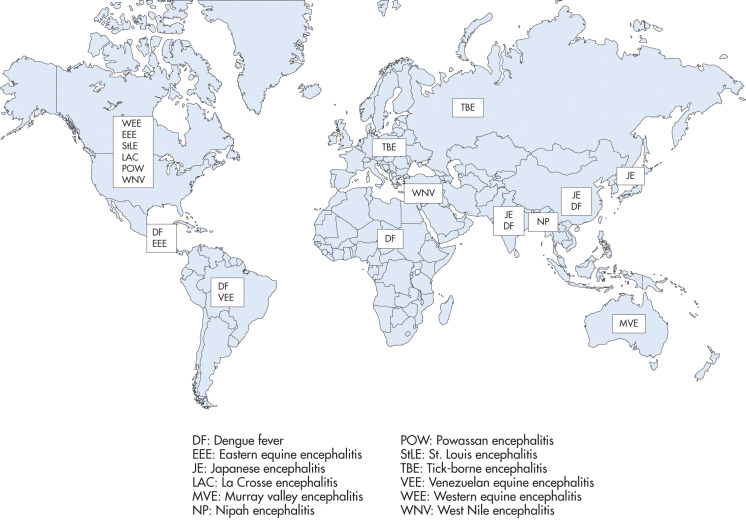

- Geography also plays a role (Fig. E1): Whereas Eastern equine encephalitis is more likely on the East Coast of U.S., West Nile virus has spread to 48 states. Powassan virus is more common in northern New England and Canada. La Crosse virus is more common in the upper Midwestern and mid-Atlantic and southeastern states.

- Can be caused by a host of viruses (Table E1), with herpes simplex the most common virus identified

- Arboviruses transmitted by mosquitoes include Eastern equine encephalitis, Western equine encephalitis, St Louis encephalitis, Venezuelan equine encephalitis, California virus encephalitis, Japanese B encephalitis, La Crosse encephalitis, Murray Valley and West Nile encephalitis. Tick-borne diseases (Table 2) include Russian spring-summer encephalitis, Powassan encephalitis, and other lesser known agents

- Also implicated: Rabies-causing agents, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr, varicella-zoster, echo virus, mumps, adenovirus, coxsackie, rubeola, and herpes viruses

- Meningoencephalitis: Acute retroviral infection from HIV

- In the U.S., the most commonly identified etiologies are herpes simplex virus, West Nile virus, and the enteroviruses

TABLE 2 Representative Tick-Borne Encephalitis Viruses

| Virus Name | Family Taxonomy | Geographic Distribution | Tick Vectors | Wild Animal Reservoirs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central European tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV-Eu) | Flaviviridae | Europe, except Iberian Peninsula | Ixodid ticks, especially Dermacentor marginatus, Ixodes persulcatus, and Ixodes ricinus | Mammals: especially rodents, including hedgehogs, wood mice, and voles; also deer and other ungulates, birds, and domestic livestock, especially goats |

| Deer tick virus | Flaviviridae | U.S. New England states (Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York) | Ixodes scapularis | Deer |

| Far Eastern TBEV (TBEV-FE) | Flaviviridae | Eastern Russia, China to far eastern Japan | I. persulcatus | Mammals: rodents, including hedgehogs, wood mice, voles; also birds, deer, other ungulates, and domestic livestock, especially goats |

| Langat virus | Flaviviridae | Malaysia | Ixodid ticks | Mammals: monkeys, rodents |

| Louping ill virus | Flaviviridae | U.S., Scotland | Ixodid ticks | Sheep |

| Powassan encephalitis virus | Flaviviridae | Canada, U.S. Northeast, far eastern Russia | Ixodes spp., particularly I. scapularis, I. cookei; Dermacentor andersoni | Mammals: rodents, skunks, and other medium-sized mammals, especially woodchucks |

| Siberian (Russian) spring-summer TBEV (TBEV-Sib) | Flaviviridae | Russia | Ixodes spp., particularly I. persulcatus, I. ricinus | Mammals: rodents, including hedgehogs, wood mice, voles; also birds, deer, other ungulates, and domestic livestock, especially goats |

| Turkish sheep encephalitis virus | Flaviviridae | Turkey | Ixodid ticks | Sheep |

| Bhanja virus | Bunyaviridae | Eastern Europe, Russia, central and West Africa | Dermacentor spp.; Haemaphysalis intermedia | Cattle, sheep, goats, hedgehogs |

| Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus | Bunyaviridae | Asia, Eastern Europe, Africa, Middle East | Hyalomma marginatum, Hyalomma anatolicum | Mammals: many domestic animals (buffalo, camels, cattle, goats, sheep), rabbits, rodents (hedgehogs), birds |

From Bennett JE et al: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases, ed 9, Philadelphia, 2020, Elsevier.

TABLE E1 Encephalitis (With a Focus on Immunocompetent Patients and Pathogens in the United States)

| Etiology | Association With Encephalitis | Epidemiology | Clinical and Laboratory Hallmarks | Recommended Tests and "Pitfalls" |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viruses | ||||

| Adenovirus | Mostly anecdotal data; unclear neurotropic potential | Sporadic; children and immunocompromised persons at greatest risk | Respiratory symptoms common | Viral culture or PCR from respiratory site, CSF, or brain tissue |

| Eastern equine encephalitis virus | Proven neurotropic potential, but uncommon | Atlantic and Gulf U.S. states | Subclinical to fulminant; 50%-70% mortality | Serology |

| Enteroviruses (include coxsackieviruses and enterovirus 71) | Most common cause of encephalitis in pediatric population | Highest incidence in late summer and early fall but can occur year round; large outbreaks of enterovirus 71 infection in Asia have occurred | Aseptic meningitis most common but also encephalitis; hand, foot, and mouth rash may be present; enterovirus 71 can cause rhombencephalitis | CSF PCR single best test but not always sensitive; to increase sensitivity of detection add serum/plasma, throat PCR, or culture |

| Epstein-Barr virus | Relatively common | During acute infection | Infectious mononucleosis during acute infection, cerebellar ataxia, sensory distortion ("Alice-in-Wonderland" syndrome) | Serology and CSF PCR. Beware of PCR false-positive results (detection of low levels may represent latent infection) and false-negative results (not all cases are CSF positive) |

| Hendra virus | Less common | Endemic in Australia; associated with equine exposure | Nonspecific | Contact local health department or Special Pathogens Branch at CDC |

| Hepatitis C | Mostly anecdotal data; unclear neurotropic potential; neurologic symptoms may be related to vasculitis | Hepatitis C-seropositive patients | CSF PCR | |

| Herpes B virus | Proven neurotropic potential; rare | Transmitted by bite of Old World macaque | Vesicular eruption at site of bite followed by neurologic symptoms, including transverse myelitis | Culture and PCR of vesicles, CSF; contact CDC or Dr. Julia Hilliard |

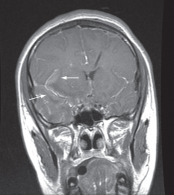

| Herpes simplex virus (HSV) types 1 and 2 | Relatively common | HSV type 1 accounts for 5%-10% of encephalitis; typically a reactivation disease, HSV type 2 occurs in neonates. | Temporal lobe seizures (apraxia, lip smacking), olfactory hallucinations, behavioral abnormalities, but children often have extratemporal lesions as well | CSF PCR single best test, but false-negative results can occur; if HSE strongly suspected, repeat lumbar puncture within 3-7 days and recheck HSV PCR and intrathecal antibodies |

| Human herpesvirus-6 | Unknown, especially owing to difficult interpretation of CSF PCR false-positive results | Young children (≤2 yr) or immunocompromised patients, particularly bone-marrow-transplant recipients | May be associated with "roseola rash" | CSF PCR. Beware of false-positive findings due to chromosomal integration and latent infections |

| Human metapneumovirus | Anecdotal evidence only | Newly described; almost exclusively in children | Often with associated respiratory symptoms | Respiratory tract PCR (most CSF PCR negative) |

| Human parechoviruses | Proven neurotropic potential but frequency unknown | Children <3 yr | In young infants periventricular white matter changes resemble hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. | Parechovirus PCR (enterovirus PCR will not detect) |

| Influenza virus | Unclear neurotropic potential; good data to support flu-associated encephalopathy but unclear if encephalitis and unclear mechanism | Neurologic complications occur; sporadically reported during influenza seasons; higher numbers reported in Japan and Southeast Asia | Upper respiratory tract symptoms; CSF often acellular in 10% with bilateral thalamic necrosis | Respiratory tract culture, PCR, or rapid antigen; CSF and brain PCR infrequently positive |

| Japanese encephalitis virus | Relatively common (but only in endemic areas) | Mosquito-borne; most common worldwide cause of encephalitis; endemic throughout Asia; vaccine preventable | Seizures, parkinsonian features, acute flaccid paralysis variably seen. MRI classically shows thalamic and basal ganglia involvement. | CSF and serum antibodies |

| La Crosse virus | Relatively common | Mosquito-borne; endemic in U.S. East and Midwest; highest incidence in school-age children | Varies from subclinical illness to seizures and coma | CSF and serum antibodies |

| Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus | Rare | Highest incidence in fall and winter; rodent exposure | One of few viral causes of hypoglycorrhachia | Serology |

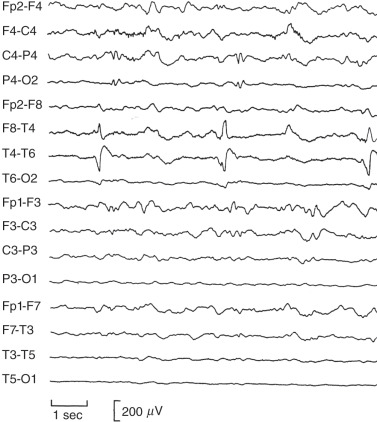

| Measles virus | Less common in countries where vaccine is routinely used | Vaccine preventable; measles inclusion body encephalitis onset 1-6 mo after infection; SSPE can manifest >5 yr after infection | Measles encephalitis nonspecific SSPE has a subacute onset with progressive dementia, myoclonus, seizures, and, ultimately, death. EEG changes are often diagnostic | |

| Mumps virus | Less common | Vaccine preventable; used to be leading cause of encephalitis-meningitis, now rarely seen | Parotitis, orchitis, hearing loss; one of few viral causes of hypoglycorrhachia | Serology, throat swab PCR, CSF culture, or PCR |

| Murray Valley encephalitis virus | Less common | Highest incidence in Aboriginal children in Australia and Papua New Guinea | Nonspecific presentation; case fatality 15%-30% | Serology (may cross react with other flaviviruses) |

| Nipah virus | Less common | Epidemics in Southeast Asia; contact with pigs | Myoclonus, dystonia, pneumonitis | Serology (Special Pathogens Branch, CDC) |

| Parainfluenza 1-4 | Unknown neurotropic potential; anecdotal evidence | Worldwide | Associated with respiratory symptoms | Respiratory DFA or PCR; CSF PCR rarely positive |

| Parvovirus B19 | Anecdotal evidence only | Sporadic cases | Variably associated with rash | IgM antibody, CSF PCR |

| Powassan virus | Less common | Tick-borne; endemic to New England, Canada | Nonspecific | Serology |

| Rabies virus | Uncommon in developed countries; relatively common in Africa, Asia, South America | Vaccine preventable; most common vector is bat (bites often unrecognized); dogs important source in developing countries; worldwide distribution | Multiple tests and assays needed for antemortem testing: Antibodies (serum, CSF), PCR of saliva or CSF, IFA of nuchal biopsy, or CNS tissue. Coordinate testing with health department. | |

| Rotavirus | Correlation with seizures in young child but unclear association with encephalitis | Typically children; winter; vaccine preventable | Usually with diarrhea | Stool antigen, CSF PCR (CDC) |

| Rubella virus | Less common in countries where vaccine is routinely used | Vaccine preventable | Neurologic findings typically occur at same time as rash and fever | Serology, CSF antibodies |

| St Louis encephalitis virus | Relatively common | Mosquito-borne; endemic to western U.S.; occasional outbreaks in central/eastern U.S.; highest incidence in adults >50 yr | Tremors, seizures, paresis, urinary symptoms, SIADH variably present | Serology (cross reacts with other flaviviruses) |

| Tick-borne encephalitis virus | Relatively common in affected geographic areas | Vaccine-preventable; transmitted via tick or ingestion of unpasteurized milk; endemic to Asia, Europe, and areas of former Soviet Union | Weakness ranging from mild paresis to acute flaccid paralysis | Serology |

| Vaccinia | Less common | Primarily associated with vaccination | Vaccinia rash (localized or disseminated) | CSF antibodies, serum IgM (natural infection) |

| Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus | Less common | Central and South America; sometimes in U.S. border states (Texas, Arizona) | Myalgias, pharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection variably present | Serology, viral cultures (blood, oropharynx), CSF antibody |

| Varicella zoster virus | Relatively common | Acute infection (chickenpox) or reactivation (shingles) | Vesicular rash (disseminated or dermatome), cerebellar ataxia, large vessel vasculitis | DFA or PCR of skin lesions, CSF PCR, serum IgM (acute infection) |

| Western equine encephalitis virus | Less common | Onset in summer and early fall; western U.S. and Canada, Central and South America | Nonspecific | Serology |

| West Nile virus | Relatively common | Mosquito-borne; emerging cause of epidemic encephalitis in U.S., Europe; endemic in Middle East; highest incidence in adults >50 yr; documented transmission through organ and blood | Weakness and acute flaccid paralysis, tremors, myoclonus, parkinsonian features; MRI shows basal ganglia and thalamic lesions | CSF IgM, serum IgM/IgG, paired serology (cross reactivity with West Nile virus and SLE) |

| Bacteria | ||||

| Bartonella henselae and other Bartonella spp. | Relatively common | Often occurs after scratch or bite from kitten | Encephalopathy with seizures (often status epilepticus); peripheral lymphadenopathy; CSF is usually paucicellular | Serology (acute usually diagnostic), PCR of lymph node; CSF PCR rarely positive |

| Borrelia burgdorferi | Less common | Tick-borne infection; in U.S. and mostly in New England and eastern Mid-Atlantic states | Facial nerve palsy (often bilateral), meningitis, radiculitis; may be associated with or follow erythema migrans rash | Serology (serial EIA and western blot), CSF antibody index, CSF PCR |

| Chlamydia spp. | Anecdotal evidence only | Associated with C. psittaci and Chlamydophila pneumoniae | Often with associated respiratory symptoms | NP swab, respiratory, or CSF PCR |

| Coxiella burnetii | Less common | Animal exposures, particularly placenta and amniotic fluid | Flulike symptoms | Serology |

| Ehrlichia/Anaplasma | Relatively common | Tick-borne bacteria causing human monocytic and human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HME, HGE), respectively; HME endemic to southern and central U.S.; HGE endemic to northeastern U.S. and Midwest | Acute onset of fever and HA; rash seen in <30% of cases; leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated LFTs frequent manifestations | Morulae in white blood cells, PCR of whole blood, serology (seroconversion may occur several weeks after symptoms) |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | One of most frequently identified agents in case series but mostly anecdotal evidence | Worldwide distribution | Respiratory symptoms variably present, but pneumonia rare; often with white matter involvement consistent with ADEM | PCR of NP swab or respiratory culture, serum IgM; CSF PCR rarely positive |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Relatively common | Most common in developing countries; disease of very young and very old or immunocompromised | Subacute basilar meningitis, lacunar infarcts, hydrocephalus; CSF often with low glucose, high protein levels; pulmonary findings often associated | CSF AFB smear, culture, PCR, respiratory cultures highly suggestive |

| Rickettsia rickettsii | Relatively common in affected geographic areas | Tick-borne infection in North America; highest incidence in southeast and south central U.S. | Acute onset of fever and headache; petechial rash in 85% of cases beginning 3 days after onset of symptoms | Serology (seroconversion may occur several weeks after symptoms), PCR or IHC on skin biopsy of rash |

| Treponema pallidum | Rare (especially in pediatrics) | Sexually transmitted disease; meningoencephalitis in early disseminated disease; progressive dementia in late disease | Protean manifestations, including temporal lobe focality (mimics HSV), general paresis, psychosis, dementia | CSF VDRL (sensitive but not specific), serum RPR with confirmatory FTA-ABS |

| Tropheryma whippelii | Rare (especially in pediatrics) | Progressive subacute encephalopathy, oculomasticatory myorhythmia pathognomonic; variable enteropathy, uveitis | CSF PCR, PAS-positive cells in CSF, small bowel biopsy | |

| Protozoa | ||||

| Acanthamoeba spp. | Less common; more common in immunocompromised | Worldwide, inhalation of wind-blown soil | Subacute progressive | Contact CDC/Parasitology |

| Balamuthia mandrillaris | Less common | Worldwide (but most case reports in U.S. and South America), inhalation of wind-blown soil | Subacute progressive disease characterized by space-enhancing lesions, often with cranial nerve palsies and hydrocephalus (similar to tuberculosis) | Serology (research laboratories), brain histopathology, CDC laboratories Contact CDC/Parasitology for testing |

| Naegleria fowleri | Less common | Summer; swimming or diving in brackish water or poorly chlorinated pools | Anosmia, progressive obtundation; CSF resembles bacterial meningitis, but sterile | Mobile trophozoites on wet mount of warm CSF, brain histopathology |

| Toxoplasma gondii | Rare in normal hosts | Worldwide; cats definitive hosts but humans often infected via consumption of undercooked meats, unwashed produce | ||

| Helminths | ||||

| Angiostrongylus cantonensis | Most common cause of eosinophilic meningitis worldwide; rare in U.S. | In the U.S. in Louisiana and Hawaii; South Pacific, Asia, Australia, and Caribbean | Meningitis or encephalitis; eosinophils in CSF; also associated with eosinophilic pneumonitis | Identification of worm in tissues |

| Baylisascaris procyonis | Less common | North America, Europe, and Asia; pica, particularly near raccoon latrines | Obtundation, coma; significant CSF and peripheral eosinophilia | CSF and serum antibodies; contact CDC/Parasitology for testing |

| Gnathostoma spinigerum | Relatively common in affected geographic areas | Southeast Asia, some areas of South/Central America; undercooked freshwater fish, chicken, or pork; also reported with reports of ingestion of frogs/snakes | Eosinophilic myeloencephalitis; can cause intermittent symptoms for 10-15 yr because larvae are long-lived | Identification of worm in tissues |

| Fungi | ||||

| Coccidioides spp. | Relatively common | Southwest U.S., northern Mexico, areas of Central and South America | Neurologic manifestations are result of disseminated disease; more often meningitis than encephalitis; CSF eosinophils sometimes seen | CSF fungal culture (but need to alert laboratory); CSF and serum antigen and antibody. EDTA-heat-treated antigen increases sensitivity of CSF and serum |

| Histoplasma capsulatum | Relatively common | Eastern and central U.S., especially Mississippi, Ohio, and Missouri River valleys; grows on mold, bird, and bat droppings; especially found in caves, barns, or excavation areas | Neurologic manifestations are result of disseminated disease | CSF fungal culture; CSF and serum antigen and antibody. EDTA-heat-treated antigen increases sensitivity of CSF and serum. Urine antigen |

| Blastomyces dermatitidis | Relatively common | Southeast, central, and midwestern U.S.; also in Canada, Africa, and India | Neurologic manifestations are result of disseminated disease | CSF fungal culture; CSF and serum antigen and antibody. EDTA-heat-treated antigen increases sensitivity of CSF and serum |

ADEM, Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis; AFB, acid-fast bacilli; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CNS, central nervous system; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; DFA, direct fluorescent antibody test; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; EEG, electroencephalogram; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; FTA-ABS, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test; HA, hemagglutination assay; HGE, human granulocytic ehrlichiosis; HME, hepatomyoencephalopathy; HSE, herpes simplex encephalitis; HSV, herpes simplex virus; IFA, indirect fluorescent antibody test; Ig, immunoglobulin; IHC, immunohistochemistry; LFTs, liver function tests; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NP, nasopharyngeal; PAS, periodic acid-Schiff; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; SIADH, syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SSPE, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory.

From Cherry JD et al: Feigin and Cherry’s pediatric infectious diseases, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2019, Elsevier.

- Initially, fever and evidence of meningeal irritation

- Headache and stiff neck

- Later, development of signs of cortical dysfunction: Lethargy, coma, stupor, weakness, seizures, facial weakness, as well as brainstem findings

- Cerebellar findings: Ataxia, nystagmus, hypotonia, myoclonus, cranial nerve palsies, and abnormal tendon reflexes

- Patients with rabies: Hydrophobia, anxiety, facial numbness, psychosis, coma, or dysarthria

- Rarely, movement disorders, such as chorea, hemiballismus, or dystonia

- Recall of a prodromal viral-like illness (this finding is not at all uniform)

- Skin/mucous membrane findings suggesting specific viral central nervous system diseases are described in Table 3

- Table 4 summarizes other specific findings associated with viruses causing central nervous system disease

TABLE 4 Other Specific Findings Associated With Viruses Causing Central Nervous System Disease

| Finding | Viruses | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alopecia | LCMV | ||

| Arthritis | LCMV, parvovirus, chikungunya | ||

| Biphasic illness | LCMV, Colorado tick fever | ||

| Lymphadenopathy | LCMV, mumps, HIV | ||

| Mastitis | Mumps | ||

| Mononucleosis | HCMV, EBV, CMV | ||

| Myelitis | WNV, St Louis encephalitis virus, VZV, EBV, HSV-1, CMV, herpes B virus, LCMV, EV-D68, EV-A71 | ||

| Myocarditis/pericarditis | Enterovirus, (mumps, LCMV) | ||

| Orchitis/oophoritis | Mumps (LCMV, EBV) | ||

| Paresthesias | Colorado tick fever, LCMV, rabies | ||

| Parotitis | Mumps (LCMV) | ||

| Pneumonia | Influenza, parainfluenza, SARS-CoV2 | ||

| Retinitis | HCMV, WNV, ZIKV (congenital) | ||

| Tremors, myoclonus | Arbovirus (e.g., WNV), EV-A71 | ||

| Urinary retention | St Louis encephalitis virus, VZV, HCMV, HSV, herpes B virus, LCMV (see myelitis causing viruses) |

EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; EV, enterovirus, HCMV, human cytomegalovirus; HSV, herpes simplex virus type; LCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus; VZV, varicella-zoster virus; WNV, West Nile virus; ZIKV, Zika virus.

From Jankovic J et al: Bradley and Daroff’s neurology in clinical practice, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.

TABLE 3 Skin/Mucous Membrane Findings Suggesting Specific Viral Central Nervous System Diseases

| Exanthem or Mucous Membrane Change | Viral Agent | Specific Changes |

|---|---|---|

| Vesicular eruption | Enterovirus (A71) | "Hand, foot, and mouth disease": Macules/papules/vesicles on palms, soles, buttocks |

| Herpes simplex | Grouped small (3 mm) vesicles on an erythematous base | |

| Varicella-zoster virus | ||

| Maculopapular eruption | Epstein-Barr virus | Diffuse maculopapular eruption following ampicillin treatment |

| Measles | Diffuse maculopapular erythematous eruption beginning on face/chest and extending downward | |

| HHV-6 | Roseola: Diffuse maculopapular eruption following 4 days of high fever | |

| Colorado tick fever | Maculopapular rash in 50% | |

| LCMV | Occasionally occurs with lymphadenopathy | |

| WNV, ZIKV | Diffuse erythematous maculopapular rash on chest and arms | |

| Erythema multiforme | (Mycoplasma) | Many types of rash |

| Confluent macular rash | Parvovirus | Confluent erythema over cheeks ("slapped cheeks") followed by lacy reticular rash over extremities (late) |

| Purpura | Parvovirus | Rare "stocking glove" syndrome: Purpuric lesions on distal extremities |

| Pharyngitis | Enterovirus | Herpangina: Vesicles on soft palate |

| Adenovirus | Pharyngitis, conjunctivitis | |

| Conjunctivitis | St Louis encephalitis | Conjunctivitis |

| ZIKV | Conjunctivitis | |

| Adenovirus | Conjunctivitis with pharyngitis (see above) |

HHV-6, Human herpesvirus type 6; LCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus; VZV, varicella-zoster virus; WNV, West Nile virus; ZIKV, Zika virus.

From Jankovic J et al: Bradley and Daroff’s neurology in clinical practice, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2022, Elsevier.