The progression of physiologic and motor maturation aligns typically midway through the first year after birth. The infant gastrointestinal tract is able to digest and efficiently absorb virtually all nutrients by 2 to 3 months of age. Therefore, it follows that by the time complementary feeding is recommended, no foods need to be avoided on the basis of gastrointestinal tract immaturity. Developmentally, an infant should have truncal strength and stability to allow sitting in an upright position with little or no support, skills typically present between 4 and 7 months of age. The sucking, rooting, and extrusion primitive reflexes will normally have diminished by this time, and oral motor skills to handle nonliquid foods should be emerging. The gag reflex also gradually declines during this period and the infant is able to handle more complex textures.

Oral motor skills needed for greater manipulation of food within the mouth and for handling of more complex textures like thicker purees appear at approximately 6 months of age and include up-down jaw movements, tongue lateralization, and rotary motion of jaws. By the end of the first year, relatively refined chewing jaw motions and incisor teeth allow controlled bites of soft solids.

The ability to transfer objects to and across the midline, exploration of objects and food by bringing them to the mouth, and refinement of pincer grasp all develop progressively after 6 months and support self-feeding skills. Finger-feeding skills and desire are often particularly strong after 9 months of age, and preference to this over being spoon fed by an adult may be quite firm. Because effective handling of a spoon, however, does not typically develop until after 12 months of age, parents may be encouraged to offer as many finger foods as possible, to encourage self-feeding, and to support the child's emerging autonomy. Cup skills, with assistance, progressively improve between 7 and 8 months of age, and by 12 months of age, most infants are able to hold an open cup with 2 hands and take several swallows without choking. The use of sippy cups facilitates cup-drinking skills while minimizing spillage, but the spill-proof designs may also encourage grazing behavior for toddlers allowed to have continuous access to them.

The pace at which infants obtain oral motor skills and accept new tastes and textures varies widely. Parents should be encouraged to respect the pace their infant dictates, and they should be reassured that infants who are otherwise developmentally appropriate will eventually be able and willing to handle a wide variety of textures and tastes. One study found that infantile "feeding disorders" followed a final common pathway, linking an interaction between food refusal and intrusive feeding by care providers. A bidirectional pattern leading to disrupted feeding behaviors was described: either intrusive feeding by parents or caregivers led to food refusal, or an episode of infant feeding refusal was followed by an inappropriate parental or caregiver response, which then was associated with persistent disordered feeding30 (see Chapter 24: Feeding and Swallowing Disorders in Children and Infants).

The period from 6 to 8 months of age is often referred to as a critical window for initiating complementary feeding because of the developmental processes that are occurring at this time. As the infant's own desire for autonomy progresses toward the end of the first year and through the second year, the potential for conflict around being fed versus self-feeding increases.

When to Initiate Complementary Feeding (See Also Chapter 3: Breastfeeding)

Several organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), have recommended exclusive breastfeeding through about 6 months of age. The AAP supports this recommendation, stipulating introduction of complementary foods at approximately 6 months of age (see Chapter 3: Breastfeeding). A systematic review on the optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding concluded that exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months is associated with less morbidity from nonhospitalized gastrointestinal tract disease, and possibly respiratory disease, compared with mixed feeding by 3 to 4 months of age. Growth deficits were not identified with exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months or longer, although sample sizes were rarely adequate to rule out small effects on growth.31 Two randomized trials and a comprehensive systematic review preceding the DGA concluded that introduction of complementary foods at 4 to 5 versus 6 months of age was not associated with differences in growth at 6 or 12 months or at follow-up at preschool age.32,33,34 The evidence, thus, demonstrates no apparent risks for normal growth, as a general recommendation, for exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months in both industrialized and developing nations. Of note, however, is the distinction between recommendations for populations and those for individual infants, all of whom should be monitored for growth faltering or other adverse effects, and appropriate interventions should be undertaken when indicated. Similarly, health care providers should encourage responsive feeding and consider the wide variations in the attainment of oral motor and other critical developmental skills in infants when deciding when to initiate complementary feeding, as noted previously, and recently reconfirmed.35

The data supporting an effect of timing of complementary feeding on later obesity are quite limited and are mainly based on observational studies, and findings have provided mixed results. Introduction of complementary foods prior to 4 months of age is most consistently identified as contributing to later overweight.34

Timing of complementary feeding has also been examined in relation to prevention of atopic disease, including food allergies. A large systematic review concluded that there was no relationship between the age at which complementary feeding first begins and the risk of developing food allergy, atopic dermatitis/eczema, or childhood asthma.36 The AAP has, likewise, concluded that evidence does not support a strong relationship between timing of introduction of first complementary feeding and development of atopic disease in exclusively breastfed infants.37 However, there is evidence that exclusive breastfeeding for the first 3 to 4 months decreases the cumulative incidence of eczema in the first 2 years after birth. The AAP has also concluded that any duration of breastfeeding beyond 3 to 4 months is protective of wheezing in the first 2 years after birth, and a longer duration of breastfeeding, as opposed to less breastfeeding, protects against childhood asthma even after 5 years of age.37 A shift in the recommendations from the AAP and others has occurred in timing of exposure of commonly allergenic foods (eg, peanut, eggs, cow milk, soy, wheat, fish, and seafood) into infant diets. It is now generally recognized that there is no evidence that delaying the introduction of allergenic foods, including peanut, eggs, and fish, beyond 4 to 6 months prevents atopic disease. Evidence does support early introduction of infant-safe forms of peanut between 4 and 6 months of age as a means to reduce the risk for peanut allergy, especially in high-risk infants (presence of severe eczema and/or egg allergy).1,37 Data are less clear for the timing of introduction of egg. (See Chapter 31: Food Allergy in Children and AAP recommendations for further details.)

The effect of timing of introduction of complementary foods, including specific components such as gluten, on such autoimmune conditions as celiac disease and type 1 diabetes, has been of considerable interest. Two different RCTs examined the effect of gluten exposure at 4 versus 6 months of age38 or at 6 versus 12 months of age39 in high-risk infants (based on HLA typing and family history) on later development of celiac disease. Neither found an effect of early or delayed exposure on subsequent disease. Breastfeeding at the time of exposure was not protective. Systematic reviews have supported these findings, concluding that no specific recommendations related to gluten introduction or to duration of breastfeeding to prevent celiac disease were possible.40,41 Regarding type 1 diabetes, the data have been primarily observational. Systematic reviews have found that available evidence did not support recommendations about infant feeding practices, including breastfeeding or timing of gluten introduction, to alter the risk of developing diabetes, although some data suggest early and high dose exposure to gluten may reduce risk.42,43

For reasons described previously, iron and zinc deficiencies are not uncommon in older breastfed infants, with the risk progressively increasing after 6 months if iron- and zinc-rich complementary foods or supplements are not consumed. Few trials have been conducted to investigate the effect of timing of complementary feeding on zinc or other micronutrient status, and a large systematic review concluded that evidence was insufficient regarding the timing of introduction of complementary foods on outcomes related to micronutrient status.17

AAP recommendations for preventing atopic disease and complementary feeding37

There is lack of evidence to support maternal dietary restrictions either during pregnancy or lactation to prevent atopic disease.

The evidence regarding the role of breastfeeding in the prevention of atopic disease can be summarized as follows:

There is evidence that exclusive breastfeeding for the first 3 to 4 months decreases the cumulative incidence of eczema in the first 2 years of life.

There are no short- or long-term advantages for exclusive breastfeeding beyond 3 to 4 months for prevention of atopic disease.

The evidence suggests that any duration of breastfeeding beyond 3 to 4 months is protective against wheezing in the first 2 years of life. This effect is irrespective of duration of exclusivity.

There is some evidence that longer duration of any breastfeeding, as opposed to less breastfeeding, protects against asthma even after 5 years of age.55

No conclusions can be made about the role of any duration of breastfeeding in either preventing or delaying the onset of specific food allergies.

There is lack of evidence that partially or extensively hydrolyzed formula prevents atopic disease in infants and children, even in those at high risk for allergic disease.

The current evidence for the importance of the timing of introduction of allergenic foods and the prevention of atopic disease can be summarized as follows:

There is evidence that delaying the introduction of allergenic foods beyond 4 to 6 months prevents atopic disease, including peanut, eggs, and fish.

There is evidence that the early introduction of infant-safe forms of peanut reduces the risk for peanut allergies. Data are less clear for timing of introduction of egg.

The new recommendations for the prevention of peanut allergy are based largely on the LEAP trial and endorsed by the AAP. An Expert Panel has advised peanut introduction as early as 4 to 6 months of age for infants at high risk for peanut allergy (presence of severe eczema and/or egg allergy). The recommendations contain details of implementation for high-risk infants, including appropriate use of testing (specific IgE measurement, skin-prick test, and oral food challenges) and introduction of peanut-containing foods in the health care provider's office versus the home setting, as well as amount and frequency. For infants with mild to moderate eczema, the panel recommended introduction of peanut containing foods around 6 months of age, and for infants at very low risk for peanut allergy (no eczema or any food allergy), the panel recommended introduction of peanut-containing food when age appropriate and depending on family preferences and cultural practices (ie, after 6 months of age if exclusively breastfeeding).

Current Practices in the United States for Complementary Feedings

Introduction of solid foods before 4 months of age has declined in the United States but most recent data indicate that approximately one-third of infants receive complementary foods or beverages before age 4 months, with early introduction tending to be higher in infants receiving formula compared with those who were exclusively breastfed.1,7 Also relevant to the discussion above for food choices for breastfed infants to meet iron and zinc needs, poultry was the most consumed flesh food, being consumed by 28% of 6- through 11-month-olds, and all other meats were less than 12%. The most popular category for all protein sources was mixed dishes, which tend to have a primarily starch or vegetable base, less actual meat, and correspondingly lower amounts of iron and zinc. All protein source categories increased during the second year after birth. Yogurt consumption (a good source of calcium but poor source of iron) remains a popular protein source. Fruit and vegetable consumption overall was reported by the majority in both age groups, but in the second year after birth, French fries and white potatoes were the most commonly reported vegetable. Consumption of 100% fruit juice in the first year after birth has dramatically declined to slightly less than 50% of children (coincident with its reduction in the WIC food packages); in the second year after birth, 70% reported consumption. The AAP has recommended against juice in the first year after birth and suggests limiting the amount for toddlers 1 through 3 years of age to 4 oz/day.44

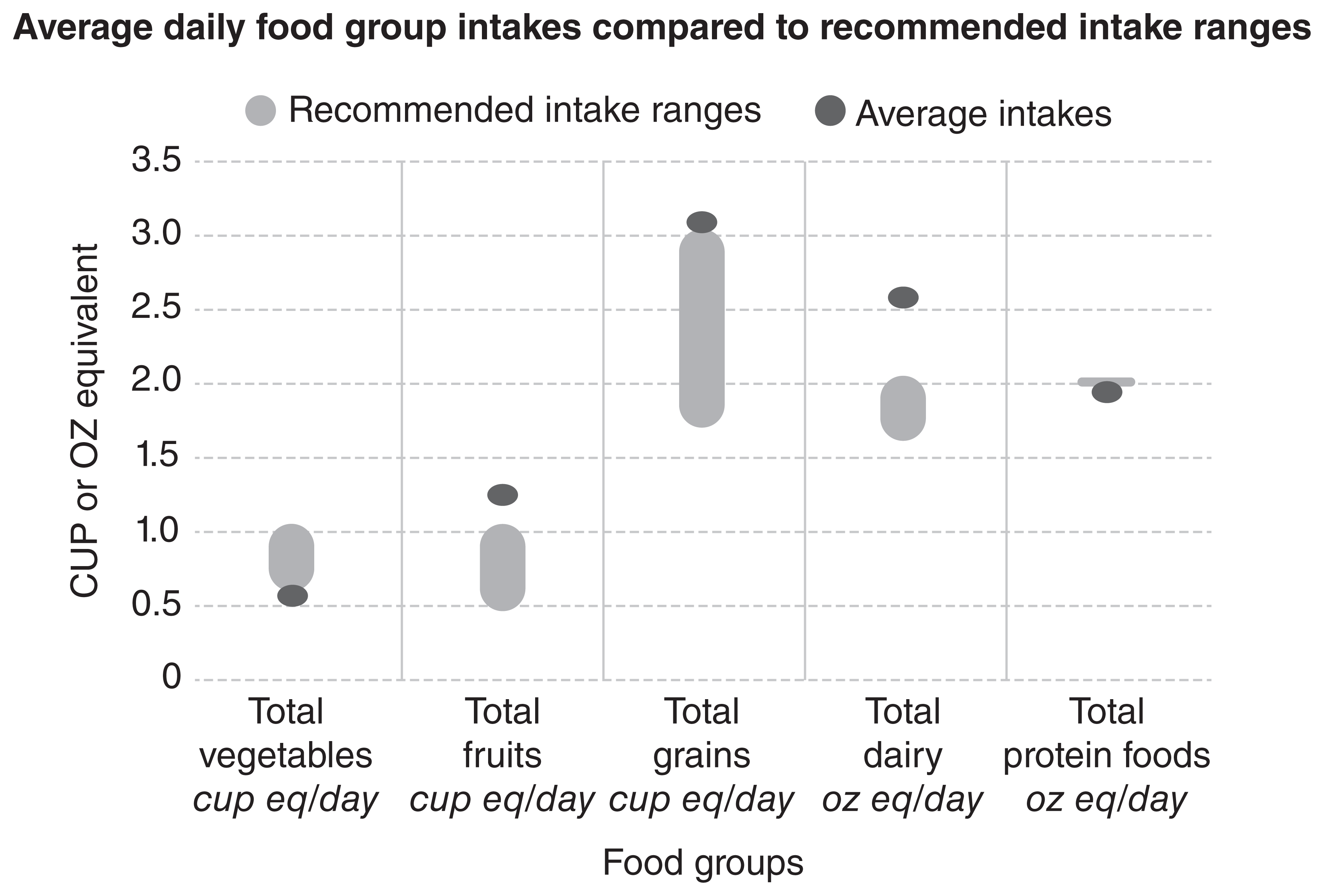

Although decreased from earlier surveys, more than 40% of 6- through 11-month-old children consumed sweet or salty snacks and desserts, and this doubled to more than 80% for 12- through 23-month-old children. Sugar-sweetened beverages were consumed by more than 50% of toddlers, with fruit-flavored drinks being the predominant type.9 From other national data and follow-up from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II,45 consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages during infancy was associated with approximately a twofold higher obesity rate at 6 years of age and was highlighted as a potential modifiable risk factor for early childhood obesity.46 Consumption of sodium and added sugars by infants and toddlers has also been identified as a concern. In contrast to commercial "infantonly" foods, which are low in sodium, high amounts of sodium and added sugars have been documented in many toddler meals and savory snacks.47,48 Additionally, sodium intake from complementary foods was significantly higher in formula fed compared to breastfed infants, with similar, though not statistically different, pattern for added sugars.7 The concerns for potentially high sugar and salt intake in commonly available foods for toddlers are twofold: accentuating innate taste preferences at a developmental stage when lifelong eating habits are being formed, and raising risk for chronic diseases (eg, obesity, hypertension) by exaggerated early exposures. A summary of current versus recommended intakes of food groups by toddlers in the United States is depicted in Fig 6.2.1

In summary, the recent national recommendations from the DGA acknowledge the distinctly different risk profiles for micronutrient deficiencies and other nutritional risks between breastfed infants and formula-fed infants (and those receiving a combination). These differences warrant tailored guidance by pediatric providers. The recommendations to mitigate risk of atopic disease-from avoidance to controlled exposure-continue to garner supportive evidence and also warrant recognition of those at risk and provision of appropriate, anticipatory guidance around feeding. Finally, although improved practices have been implemented, such as less early (before 4 months) introduction of complementary foods and less juice consumption in infants, there remain many opportunities for improvements.

Types and Amounts of Complementary Foods to Feed

As more infants are breastfed in the United States, the importance of complementary feeding patterns has gained attention. Consistent with this understanding are the formalized recommendations for infant and toddler feeding within the DGA. Tables 6.2 and 6.3 provide guidance on healthy diet pattern according to different caloric levels and key concepts, respectively. These include prioritization of nutrient dense complementary foods; introduction of potentially allergenic foods; encouragement for good variety of foods; inclusion of foods rich in iron and zinc, particularly for infants fed human milk; avoidance of added sugars; limiting added sodium; and transition to a healthy dietary pattern of family foods.1

Table 6.2. Healthy US-Style Dietary Pattern for Toddlers Ages 12 Through 23 Months Who Are No Longer Receiving Human Milk or Infant Formula, With Daily or Weekly Amounts From Food Groups1

| Calorie Level of Patterna | 700 | 800 | 900 | 1,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Group or Subgroupb,c | Daily Amount of Food From Each Groupd (Vegetable and protein foods subgroup amounts are per week.) | |||

| Vegetables (cup eq/day) | ⅔ | ¾ | 1 | 1 |

| Vegetable Subgroups in Weekly Amounts | ||||

| Dark-Green Vegetables (cup eq/wk) | 1 | ⅓ | 1/2 | 1/2 |

| Red and Orange Vegetables (cup eq/wk) | 1 | 1 ¾ | 2 ½ | 2 ½ |

| Beans, Peas, Lentils (cup eq/wk) | ¾ | ⅓ | ½ | ½ |

| Starchy Vegetables (cup eq/wk) | 1 | 1 ½ | 2 | 2 |

| Other Vegetables (cup eq/wk) | ¾ | 1 ¼ | 1 ½ | 1 ½ |

| Fruits (cup eq/day) | ½ | ¾ | 1 | 1 |

| Grains (ounce eq/day) | 1 ¾ | 2 ¼ | 2 ½ | 3 |

| Whole Grains (ounce eq/day) | 1 ½ | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Refined Grains (ounce eq/day) | ¼ | ¼ | ½ | 1 |

| Dairy (cup eq/day) | 1 ⅔ | 1 ¾ | 2 | 2 |

| Protein Foods (ounce eq/day) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Protein Foods Subgroups in Weekly Amounts | ||||

| Meats, Poultry (ounce eq/wk) | 8 ¾ | 7 | 7 | 7 ¾ |

| Eggs (ounce eq/wk) | 2 | 2 ¾ | 2 ½ | 2 ½ |

| Seafood (ounce eq/wk)e | 2-3 | 2-3 | 2-3 | 2-3 |

| Nuts, Seeds, Soy Products (ounce eq/wk) | 1 | 1 | 1 ¼ | 1 ¼ |

| Oils (grams/day) | 9 | 9 | 8 | 13 |

a Calorie level ranges: Energy levels are calculated based on median length and body weight reference individuals. Calorie needs vary based on many factors. The DRI Calculator for Healthcare Professionals, available at nal.usda.gov/fnic/dri-calculator, can be used to estimate calorie needs based on age, sex, and weight.

b Definitions for each food group and subgroup and quantity (ie, cup or ounce equivalents) are provided in Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025.

c All foods are assumed to be in nutrient-dense forms and prepared with minimal added sugars, refined starches, or sodium. Foods are also lean or in low-fat forms with the exception of dairy, which includes whole-fat fluid milk, reduced-fat plain yogurts, and reduced-fat cheese. There are no calories available for additional added sugars, saturated fat, or to eat more than the recommended amount of food in a food group.

d In some cases, food subgroup amounts are greatest at the lower calorie levels to help achieve nutrient adequacy when relatively small number of calories are required.

e If consuming up to 2 ounces of seafood per week, children should only be fed cooked varieties from the "Best Choices" list in the FDA/EPA joint "Advice About Eating Fish," available at FDA.gov/fishadvice and EPA.gov/fishadvice. If consuming up to 3 ounces of seafood per week, children should only be fed cooked varieties from the "Best Choices" list that contain even lower methylmercury: flatfish (eg, flounder), salmon, tilapia, shrimp, catfish, crab, trout, haddock, oysters, sardines, squid, pollock, anchovies, crawfish, mullet, scallops, whiting, clams, shad, and Atlantic mackerel. If consuming up to 3 ounces of seafood per week, many commonly consumed varieties of seafood should be avoided because they cannot be consumed at 3 ounces per week by children without the potential of exceeding safe methylmercury limits; examples that should not be consumed include: canned light tuna or white (albacore) tuna, cod, perch, black sea bass. For a complete list please see: FDA.gov/fishadvice and EPA.gov/fishadvice.

Table 6.3. Complementary Foods to Prioritize1

| Nutrient-dense complementary foods | Rich in nutrients important without too many calories: fruits, vegetables, whole grains, fish and seafood, unprocessed lean meats/skinless poultry, nuts and legumes |

|---|---|

| Potentially allergenic foods | Peanuts, egg, cow milk products, tree nuts, wheat, crustacean shellfish, fish, soy |

| Variety of foods from all food groups | Fruits, vegetables, grains, protein food (eg, meats, poultry, fish, legumes), dairy |

| Foods rich in iron and zinc | Meats and poultry, infant cereals (iron), legumes |

| Avoid foods and beverages with added sugars | Juice drinks, infant desserts, cereal bars, breakfast pastries |

| Limit foods and beverages higher in sodium | Toddler dinners, savory infant/toddler snacks |

| As wean from human milk or infant formula, transition to a healthy dietary pattern | Encourage dietary diversity, family foods |

With the recognition of the potential value of meats as a source of heme iron with enhanced iron absorption and as a source of bioavailable zinc, the AAP also encourages consumption of meats, vegetables with higher iron content, and iron-fortified cereals for infants and toddlers between 6 and 24 months of age.18 It is appropriate to start with meat, especially if iron-fortified infant cereal is not being provided. Absorption data suggest that 1 to 2 oz/day of meat generally provides the zinc requirement for healthy older infants and likely also for toddlers.24 Although this amount of meat is also appropriate to support iron status,20 especially if other fortified sources are included, adequacy of intakes of foods is difficult to predict for iron because of the complexity of physiologic factors that influence its absorption, as detailed earlier in this chapter (see also Chapter 18: Iron, for recommendations for screening of iron status).

A good variety of healthy foods generally promotes good nutritional status for infants and toddlers, and repeated exposures is the best way for young children to learn to accept different foods.49 Because the digestive and absorptive functions are mature well before 6 months of age, there is no reason to introduce whole food groups sequentially. Rather, considering the dynamic changes in infants' nutritional needs in the second half of the first year after birth, gradual introduction of foods across all food groups is a better paradigm. To identify adverse reactions, new foods should be introduced individually over several feeds, particularly for allergenic foods. For example, an infant cereal may be the first food, followed by meats, fruits, and vegetables. Progression to foods from 4 food groups (grains, meats, fruits, and vegetables) could reasonably be achieved within the first month of complementary feeding. Amounts of each food and variety are expected to gradually increase with the infant's age. Infants have been demonstrated to accept cereals and meats equally well by 5 months of age.50 Although formula-fed infants are less dependent on specific food choices to avoid micronutrient deficiencies than are predominantly found in breastfed infants, exposure to all food groups in infancy provides important familiarity for the second year after birth, when fortified formula will no longer be consumed by most toddlers.

Food choices to be encouraged, whether home or commercially prepared, are those with no added salt or sugar; as detailed above, this is especially important for commercial foods marketed for toddlers. Fats, particularly healthy fats, such as those containing mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids-for example, avocado, ground nuts or nut butters, and olive and canola oils-should be encouraged. Energy intakes of older infants and toddlers are notoriously difficult to measure, and energy requirements are difficult to estimate. Appropriateness of energy intake for an individual child is best judged by appropriateness of growth.