Information ⬇

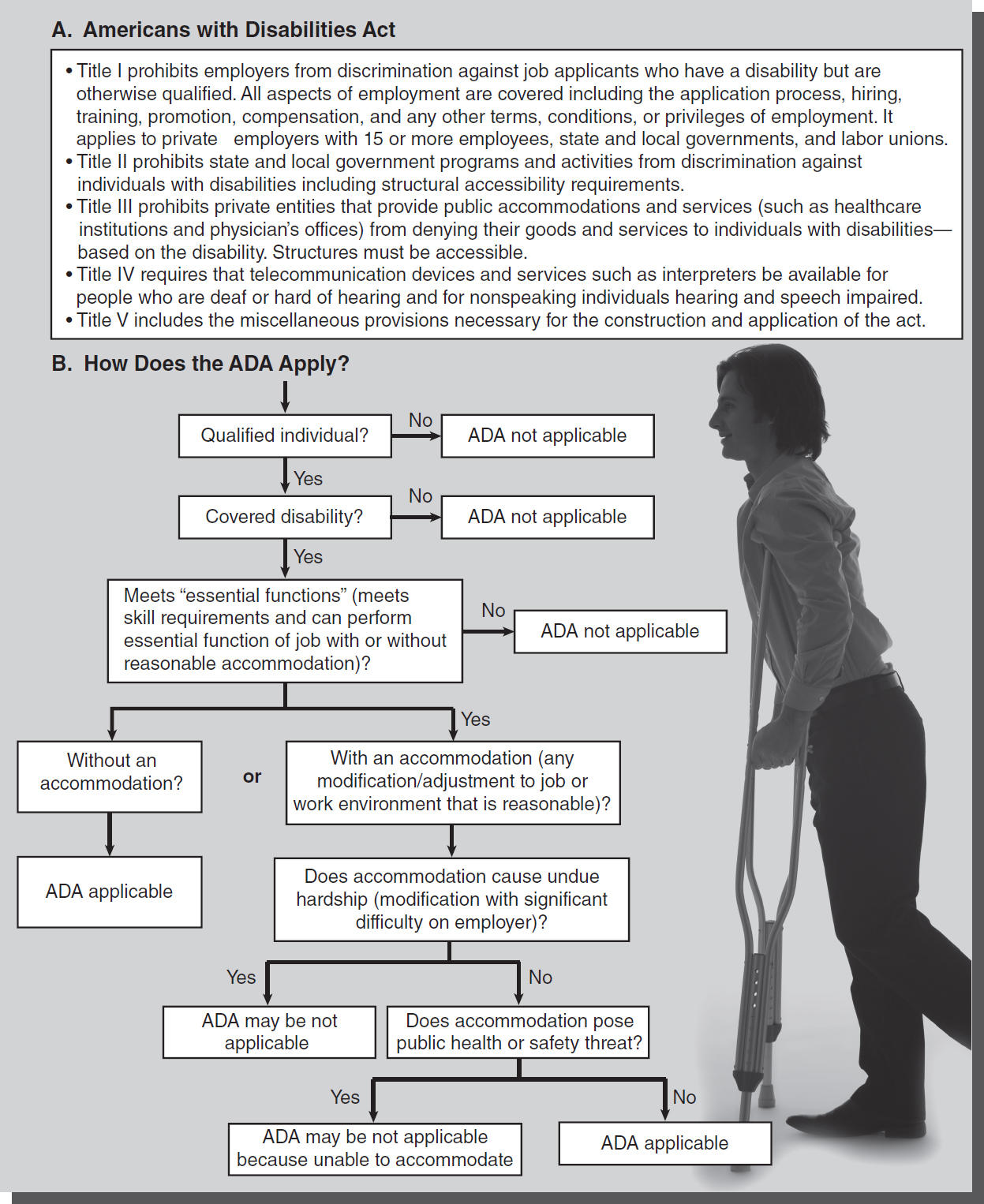

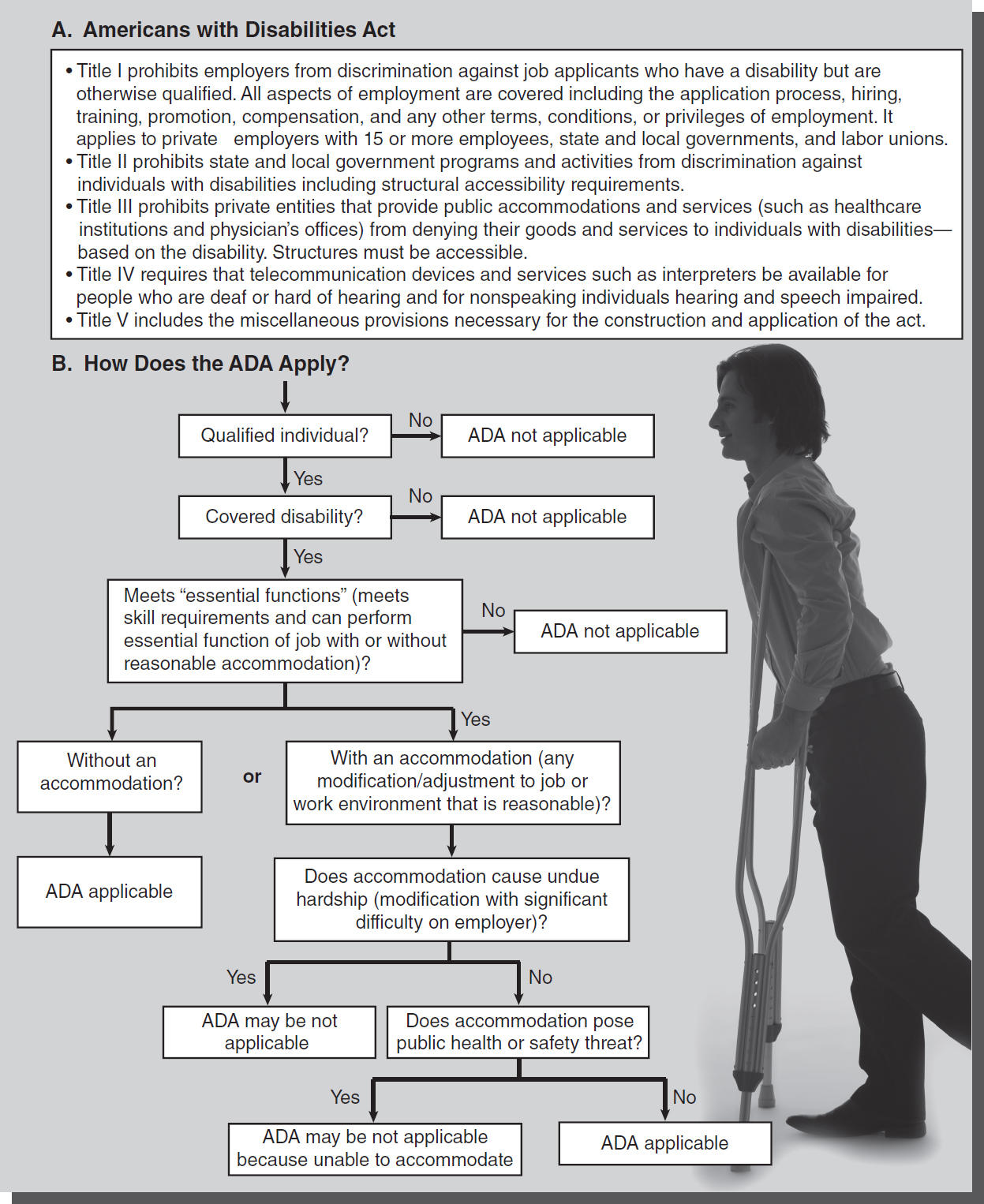

Figure 38-1 Features and application of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

© Jones & Bartlett Learning; © Comstock Images/Thinkstock

Congress passed the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990 with the goal of encouraging individuals with disabilities to participate in work and social environments by discouraging discrimination. The law is intended to balance the needs of citizens who have disabilities with the ability of public and certain private entities to reasonably accommodate those needs without causing an undue hardship. The act does not give any individual an unfair advantage. It seeks to end discrimination of qualified individuals with disabilities by removing barriers that would prevent them from the same opportunities as others. The ADA has five titles (see

Figure 38-1A). In 2008, the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act (ADAAA) was passed. This act emphasizes that the definition of disability should be construed in favor of broad coverage for individuals to the maximum extent permitted by the terms of the ADA. The effect of these changes is to make it easier for individuals seeking protection under the ADA to establish that they have a disability within the meaning of the ADA. The ADAAA became effective in 2009, and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission's regulations to implement the act became effective as of March 2011 (

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2008).

Covered Disabilities and Reasonable Accommodations ⬆ ⬇

The ADA applies to those with a disability that substantially limits major life functions. A disability is defined as a mental or physical condition that substantially limits a major life activity, such as seeing, hearing, speaking, walking, breathing, performing manual tasks, learning, caring for oneself, and working. The act is clearer on what it does not cover, including some temporary conditions, such as a broken leg, and impairment from current illegal drug use. Covered disabilities are constantly evolving, but generally the act applies to alcohol use disorder, epilepsy, paralysis, HIV disease, AIDS, intellectual disability, and specific learning disabilities.

A qualified individual with a disability is one who meets the skill, experience, education, or other requirements of employment and can perform the “essential functions” of the position with or without a “reasonable accommodation.” The term essential functions refers to the ability to perform the job requirements with the exception of marginal or incidental job functions. Reasonable accommodation is any modification or adjustment to the job or work environment that will assist the qualified individual to perform essential job functions. This includes adjustments that give the qualified individual the same rights and privileges enjoyed by other employees. When a qualified individual can perform essential job functions (except for marginal functions), the employer must consider whether the individual could perform those functions with a reasonable accommodation. The employer is only required to accommodate a known disability. Employers are not required to lower the quality of standards and are not obligated to create a position that does not exist. Undue hardship is an “action requiring significant difficulty or expense.” An accommodation for the qualified individual must not pose an undue hardship on the employer. Undue hardship is not the only limitation on an employer's requirement to reasonably accommodate a qualified individual. Public safety and health must always be considered (see Figure 38-1B).

Hospitals are not required to eliminate essential job functions such as lifting, moving, or positioning patients or equipment. Therefore, a reasonable accommodation did not exist when the nurse had an injury that limited her ability to perform these functions (Gunertne v. St. Mary's Hospital, 1996; Stafford v. The Radford Community Hospital Inc., 1995). An offer of an inferior position with fewer benefits is not a reasonable accommodation (Norville v. Staten Island University Hospital, 1999).

How the ADA Affects Nurses as Employees in the Preemployment Phase ⬆ ⬇

The employer may not ask an applicant to take a medical examination before a job offer is made. Employers may not make a preemployment inquiry into a disability but may ask about a disability as it applies to the performance of specific job functions. Employers may condition job offers on a post-job offer physical examination that is required of all employees at the same level. The reason for not hiring an applicant after a post-offer physical examination must be related to business necessity. Testing for illegal drug use is not considered a medical examination; therefore, an employer may test and make employment decisions based on the results. However, this information must be treated the same as a confidential medical record.

An employer may establish qualifications standards that exclude qualified individuals with a disability who pose significant risk of substantial harm known as a “direct threat” to the health and safety of others, but only if the direct threat is not eliminated or minimized by a reasonable accommodation. The employer must use objective, medically sound reasoning to establish the risk. As one example, the employer might prohibit the ability of a nurse living with HIV (a disability under the ADA) from working in the operating room or in labor and delivery because HIV is transmitted through blood and there may be a greater potential for blood exposure in these environments (see Chapter 39).

How the ADA Affects Nurses as Employees ⬆ ⬇

Employers are only required to accommodate a known disability; therefore, the employee is responsible to tell the employer of a need for an accommodation. The employee may disclose only as “a disability under ADA” with the need for accommodation, but the employer may ask for medical documentation. The employer is then required to take steps to ensure confidentiality by separating medical records from the employee personnel file.

Uniformly applied leave policies do not violate the ADA when there is no apparent discrimination to the worker with a disability. However, the employer may be required to modify a leave policy upon a qualified individual's request unless it would cause an undue hardship.

The ADA differs from workers' compensation programs in that workers' compensation applies when an employee is injured on the job. A work injury would have to fit into the act's criteria for a qualified individual to also fall under the protection of the ADA.

Advocacy for Inclusion of Nurses with Disabilities in the Workplace ⬆ ⬇

There has been increased focus on nurses with disabilities in the workplace in recent years, and the contributions they can make in healthcare settings. Some authors have challenged the profession to include more nurses with disabilities in both nursing care and nursing education settings, and to question previously held beliefs and biases that may have constrained nurses who have disabilities in the past. Neal-Boylan, Marks, and McCulloh (2015) reported on a policy roundtable where the National Organization of Nurses with Disabilities (NOND) and the U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Disability Employment Policy participated and advocated for this group. NOND advises nurses with disabilities to become familiar with their rights under the ADA and ADAA and to seek accommodations to fully participate in professional nursing.

Neal-Boylan and Miller (2015) conducted a case analysis research study of 56 law cases where nurses' claims were related to their disabilities. Most were found to be discrimination claims, usually based on an adverse employment action, and the findings help to clarify under what circumstances nurses may have a successful or unsuccessful claim. The authors stated that if some of these 56 cases (those analyzed were between the years 1995 and 2013) were litigated under the more recent ADAA legislation, there might have been more likelihood of success. Nevertheless, important information was gleaned from this study to inform nurses with disabilities of their rights as based on case law.

According to Marks and Sisirak (2022), disability awareness and inclusion is a part of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts in the healthcare workforce. They advocate the importance of addressing the ongoing exclusion of students with disabilities from entering the nursing profession and barriers to securing and maintaining employment faced by nurses with disabilities. These barriers impact the ability to recognize the value and contributions of nurses with disabilities to the profession. Despite this value, the unique contributions of nurses with disabilities are not included in the functional abilities for nursing practice and nursing education programs. Excluding the functional abilities that nurses with a disability possess-those nondomain-specific activities and attributes-compromises every nurse's ability to provide safe, effective care for patients (Marks & Sisirak, 2022). The focus of caregivers needs to shift to “ableism” rather than disability in order to enhance a DEI mission. Barriers that impact nurses with disabilities must be examined. Creating a new normal for health care that includes a need for students and nurses with disabilities to incorporate their lived experience into nursing practice, and to reframe disability and illness beyond the current and often restrictive environment, is imperative. Many nurses with disabilities have successfully completed nursing programs and are actively working successfully in clinical and other nursing roles.

Public Accommodations in the Healthcare Setting ⬆ ⬇

Physicians' offices, pharmacies, inpatient and outpatient healthcare institutions, and long-term care facilities fit into the act's definition of public accommodations. The act also considers establishments that provide a “significant” amount of social services to be places of public accommodations. Therefore, certain group homes, independent living centers, and retirement communities will come under the act if they provide enough social services.

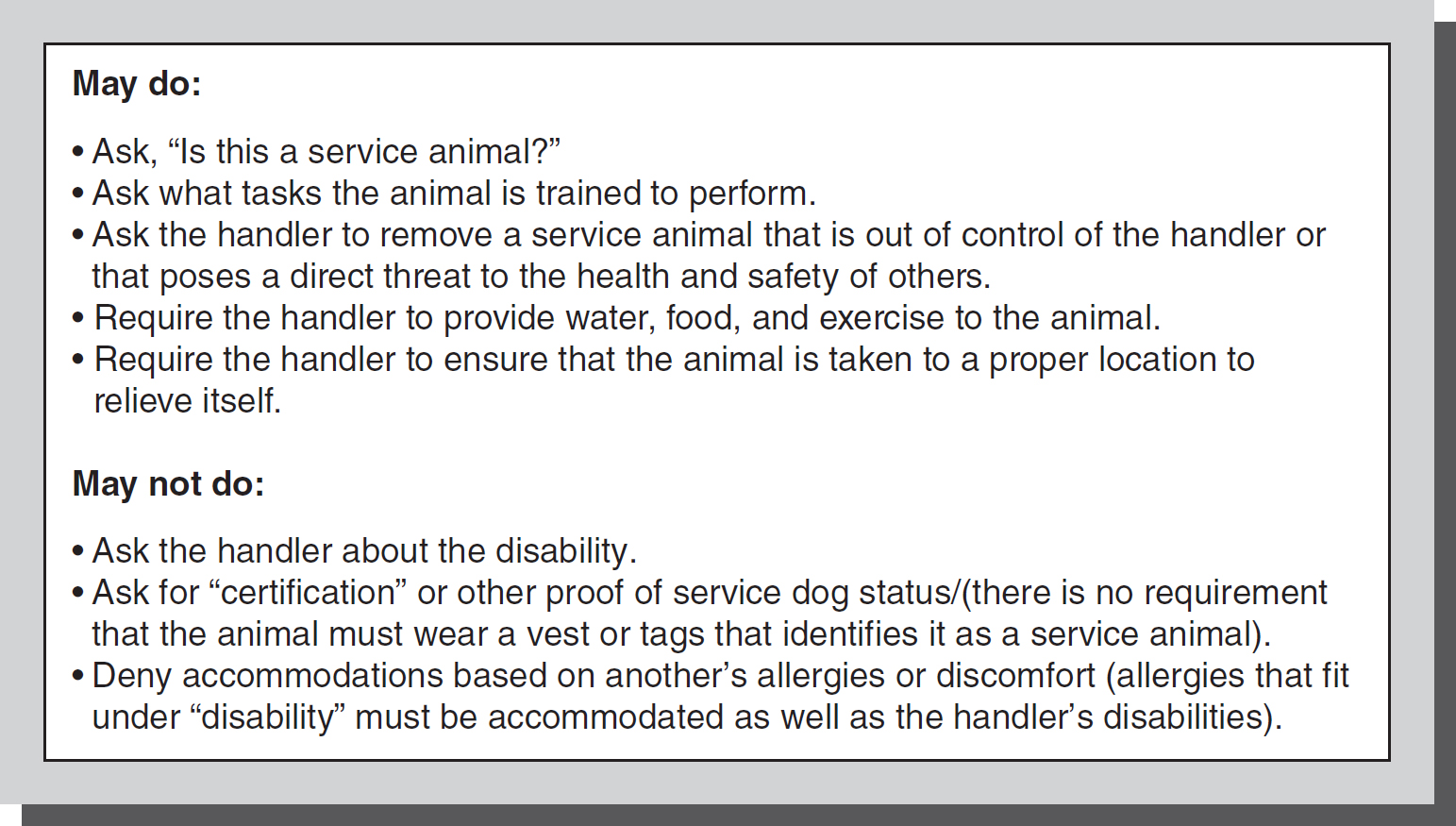

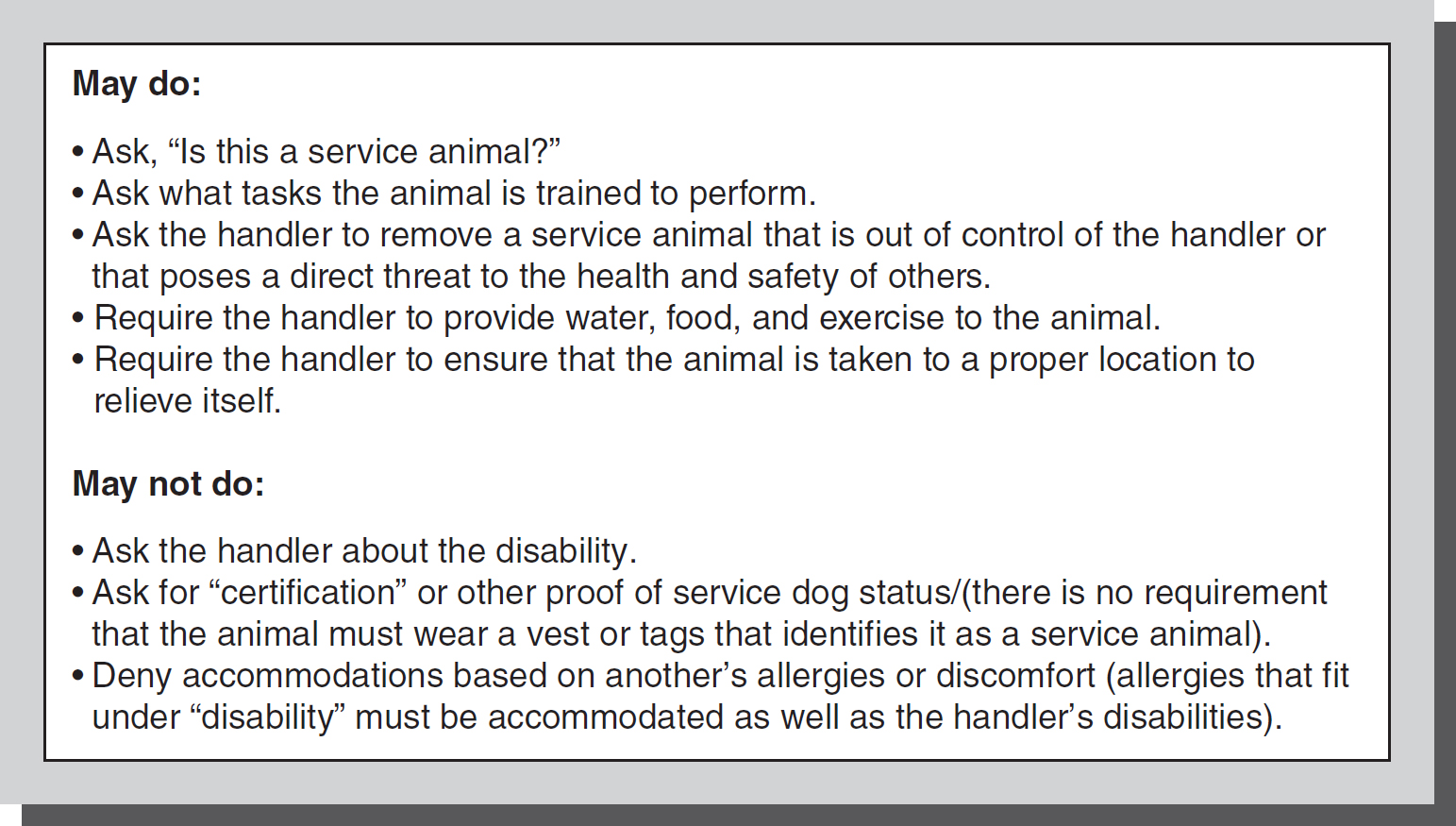

As public accommodations, healthcare providers must provide access to these services by accommodating “service animals” that are trained to perform tasks for the handler. Service animals differ from therapy animals that provide comfort. Therapy animals are recognized as clinically beneficial but do not provide a task under the ADA.

How the Act Affects Nurses as Healthcare Providers ⬆ ⬇

Public accommodations, such as healthcare institutions and physicians' offices, must provide auxiliary aides and services. Individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing should be provided with qualified interpreters, assistive listening devices, note takers, or written material. People who are blind or have low vision must be provided with qualified readers, taped texts, large-print or Braille materials, or computer-assisted devices to accommodate their disability.

There are limits to the length a public accommodation must go to reasonably accommodate individuals with disabilities, such as a direct threat to public health and safety or a fundamental disruption to services provided. Service animals are a medical necessity for the handler; therefore, local health codes that prohibit animal entry for infection control and food service safety do not apply. Accommodation of the service animal in the healthcare setting includes ensuring there is no direct threat to public safety and health by consulting the infectious disease department, providing a private room, and reassigning staff members who have allergies. Staff members are not required to care for the animal, because handlers are responsible to provide care or make care arrangements if they are unable to do so personally. The accommodation need only be reasonable and not cause a fundamental disruption to providing healthcare services (see Figure 38-2).

Figure 38-2 Service animals and the ADA.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning

As patients' advocates, nurses must always be aware of their institution's policy on providing auxiliary aides to a patient with a disability or a patient's family member with a disability. Having such a policy in place does not shield a hospital from liability when the nurses do not know how to implement the policy.

Remedies for Noncompliance ⬆ ⬇

The ADA provides plaintiffs in private causes of action with an injunction against the defendant. Upon finding a violation of the act, the court may order an injunction, which prohibits the defendant from continuing the unlawful behavior or commands the defendant to correct any wrong done to the plaintiff. Monetary remedies are not generally available under the act except in specific circumstances. The attorney general must be involved in the case and make a request in federal court for the plaintiff to be awarded monetary damages. The attorney general usually makes the request in cases where the defendant has established a pattern of discriminatory behavior or exhibits discriminatory conduct that rises to the level of public concern. In those cases, the court may grant an injunction, award monetary damages to the aggrieved party, and assess a civil penalty. The court will take into consideration any good faith effort by the defendant to comply with the act.

References ⬆ ⬇

- Gunertne v. St. Mary’s Hospital, 943 F.Supp. 771 (S.D. Tex. 1996).

- Marks , B., & Sisirak , J., (2022). Nurses with disability: Transforming healthcare for all, Online Journal of Issues in Nursing (OJIN), 27, (3) https://web-p-ebscohost-com.scsu.idm.oclc.org/ehost/detail/detail?vid=3&sid=8796e74b-48a8-4bde-902d-2d8f0c5c64a0%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#AN=161759061&db=aph

- Neal-Boylan , L., Marks , B., & McCulloh , K. J. (2015). Supporting nurses and nursing students with disabilities. AJN, 115(10), 11.

- Neal-Boylan , L. & Miller , M. D. (2015). Registered nurses with disabilities: Legal rights and responsibilities. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 47(3), 248-257.

- Norville v. Staten Island University Hospital, 196 F.3d 89 (2d Cir. 1999).

- Stafford v. The Radford Community Hospital Inc., 908 F.Supp. 1369 (W.D. Va. 1995).

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2008). Notice concerning the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Amendments Act of 2008. http://www.eeoc.gov/laws/statutes/adaaa_notice.cfm?renderforprint=1

Additional Resources ⬆

- Elting, Julie Kientz (2024). Breaking barriers: Nursing education in a wheelchair. American Nurse Journal, 19(5), 14-18. Doi: 10.51256/ANJ052414

- The National Organization of Nurses with Disabilities:http://www.nond.org