Decreased central vision; may be sudden or gradual. Central or paracentral scotomas.

Critical

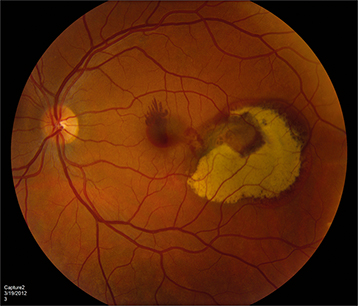

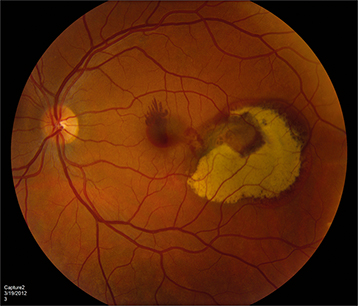

Subretinal red-orange, polyp-like lesions of the choroidal vasculature. Can be macular (more symptomatic) or peripapillary (See Figure 11.18.1).

Figure 11.18.1: Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.

Other

Bilateral subretinal and/or sub-RPE blood, VH, circinate subretinal exudates, subretinal fibrosis (disciform scar), SRF, atypical CNV, and multiple serous PEDs.

Risk Factors

More common in females, individuals of African or Asian descent, and in patients with HTN. Can occur at a younger age compared to neovascular AMD, but usually without significant drusen or GA.

Asymptomatic lesions may be observed and may resolve spontaneously. IPCV with exudation and/or hemorrhagic complications has been treated with anti-VEGF monotherapy with or without PDT. The EVEREST-II and PLANET studies demonstrated level I evidence that anti-VEGF monotherapy as well as combination therapy give excellent functional visual outcomes in patients presenting with symptomatic IPCV. Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) can be considered for VH.

The prognosis of IPCV is generally better than for neovascular AMD. Symptomatic or macular IPCV is followed every 1 to 2 months with periodic OCT, IVFA, and ICGA as needed for disease progression. Consider treatment, or retreatment, if symptomatic, persistent, or new leakage occurs.

CheungCMG, LaiTYY, RuamviboonsukP, et al.Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: definition, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(5):708–724.

KohA, LaiTYY, TakahashiK, et al; EVEREST II Study Group. Efficacy and safety of ranibizumab with or without verteporfin photodynamic therapy for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135:1206–1213.

LeeWK, IidaT, OguraY, et al; PLANET Investigators. Efficacy and safety of intravitreal aflibercept for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy in the PLANET study: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(7):786–793.

LimTH, LaiTYY, TakahashiK, et al; EVEREST II Study Group. Comparison of ranibizumab with or without verteporfin photodynamic therapy for polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy: The EVEREST II Randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138(9):935–942.