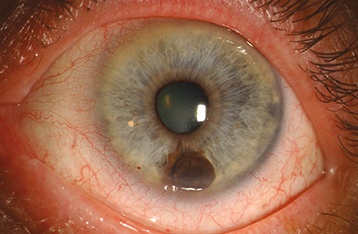

Unilateral brown or translucent iris mass lesion exhibiting slow growth. It is more common in the inferior half of the iris and in light-skinned individuals. Rare in Black patients (see Figure 5.14.1).

A localized melanoma is usually >3 mm in diameter at the base and >1 mm in depth with a variable prominent feeding vessel. Can produce a sector cortical cataract, ectropion iridis, spontaneous hyphema, seeding of tumor cells into the anterior chamber, or direct invasion of tumor into the trabecular meshwork and secondary glaucoma. A diffuse melanoma causes progressive darkening of the involved iris, loss of iris crypts, angle invasion, and increased IOP. Focal iris nodules can be present.